15 Untranslatable Russian Words and What They Mean

Russian has quite a few words and phrases (and plenty of jokes) that don’t have a direct translation into English.

This makes the transfer of ideas between the two languages messy at times.

In this post, you’ll learn 15 untranslatable Russian words and concepts and our best attempt at defining them in English.

By learning these untranslatable Russian words, you’ll be learning a bit more about the culture and language!

Contents

- What are Untranslatable Words?

- Why Are There Untranslatable Words in Russian?

- Russian Words Without an English Equivalent

- Russian Concepts That Don’t Exist in English

- How to Learn Untranslatable Russian Words

- And One More Thing...

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

What are Untranslatable Words?

Untranslatable words are terms or expressions in one language that lack an exact equivalent or counterpart in another language. These words often carry nuanced meanings, cultural contexts or emotions that are not easily captured by a single word in another language.

Untranslatable words exist in all languages due to the inherent complexity and richness of human experiences. Languages develop within specific cultures, and each culture has its own unique concepts, values and ways of perceiving the world. As a result, certain feelings, concepts or phenomena may be more prominent or relevant in one culture than in another.

Why Are There Untranslatable Words in Russian?

The Russian language is in large part a product of its environment. For instance, there’s a different Russian word for every possible type of snow and rainstorm imaginable.

There are also a few words in Russian for things that simply don’t exist anywhere else, like самовар , which is a metal teapot of sorts, usually ornate.

Other words are hard to pin down because their definitions rely too much on connotation, like the Russian дача , which can be roughly translated as “country house” but has a much deeper meaning for Russians as a historic national phenomenon.

Learning words that only exist in Russian will, of course, boost your vocabulary. They’ll also teach you about the culture of Russia, the history of the language and the values that Russians hold dear enough that they require words of their own.

Russian Words Without an English Equivalent

Below are some words that have an equivalent concept in English, but no single word to refer to it.

1. почемучка

Someone who asks a lot of questions. Think of a toddler constantly asking “почему?” (“Why?”).

You might also hear words like незнайка (know-nothing), from the phrase не знаю (I don’t know).

2. листопад

The falling of leaves in autumn, like snowfall ( снегопад ).

This one comes from the words for лист (leaf) and падать (to fall).

3. баюкать

To put a baby down to sleep while singing to them. English has similar words—to lull, to rock—but no single term that so nicely sums up the concept.

This Russian lullaby uses a variation of the term:

4. успевать

Many Russians are baffled by the fact that English doesn’t have a single word for this concept: to make it on time, or to have enough time to do something. This one word covers both definitions in a neat package:

Я успела на работу. — I made it on time to work.

Я успела поработать. — I had enough time to work.

5. сутки

While English has the word “day,” there’s no version of this Russian word, which refers to “a 24-hour period.”

6. ничего себе

Many terms in Russian that express awe are idioms that don’t translate literally, but they all have different levels of excitement and meaning.

For instance, the phrase “ничего себе!” literally means “nothing for myself!” but is used as a way of saying “I can’t believe it!”

Here are some other fun ways to show how amazed you are at something:

Вот это да! — Wow! (Literally: “Here this yes!”)

Надо же! — Wow! (Literally: “It’s needed!”)

Да ты что! — Wow, I don’t believe you! (Literally: “Yes you that!”)

Russian Concepts That Don’t Exist in English

These words are so uniquely Russian, that the very concepts they refer to don’t even exist in English.

7. тоска

You might see тоска translated as “boredom” or “melancholy.” Some dictionaries equate it to “yearning.” It means all of this and more.

The word isn’t used that often in everyday life, but has been used in Russian literature to describe that “Загадочная русская душа” (“mysterious Russian soul”).

Take it from Владимир В. Набоков (Vladimir Nabokov), a great Russian writer, who described the word as such:

“At its deepest and most painful, it is a sensation of great spiritual anguish, often without any specific cause. At less morbid levels it is a dull ache of the soul, a longing with nothing to long for, a sick pining, a vague restlessness, mental throes, yearning. In particular cases it may be the desire for somebody or something specific, nostalgia, love-sickness. At the lowest level it grades into ennui, boredom…”

A bit heavy, no? Let’s lighten things up a bit!

8. недоперепил

недоперепил literally translates to “underdrunk” or “not drunk enough.” It refers to a state of being where you’ve drunk a lot but not as much as you could (or wanted to). The word has a wistful tone, implying that you wish you’d drunk more.

So if you’re out at a bar and the barista cuts you off, you can say, “Но я же недоперепил!” (“But I haven’t yet drank as much as I can!”)

If you have a mild hangover but not the terrible bout you were expecting, you might say, “Кажется я вчера недоперепил” (“It looks like I didn’t drink to my limit yesterday”).

Russian has a few other drinking words that don’t have an English equivalent:

запой — a drinking binge that usually extends beyond a few days

опохмелиться — to drink a bit more on the day after you drank too much (about the same meaning as the expression “hair of the dog”)

9. хамство

This word can be very roughly translated to “boorishness” or “audacity,” but honestly, neither come close to the full meaning. It refers to the insolence or the rudeness of someone who doesn’t follow societal rules. You might say that it’s like “being cheeky,” but in a more severe sense.

The Russian culture has historically praised proper manners and good-naturedness, so it follows that they have a word for someone who’s poorly behaved toward others.

In fact, the language has a number of similar words that likewise don’t have true translations (though we’ll give approximate equivalents below):

наглость — impudence

грубость — rudeness in a rough sort of way

нахальство — impertinence, having nerve or gall

10. распутица

Here’s a case of a word that doesn’t have a translation simply because it describes something that doesn’t exist in English.

The распутица is a season of bad roads, a time during spring and fall when the snow and rain are so bad that they render unpaved roads practically impassable.

Some have surmised that the word has something to do with Распутин (Rasputin), but the real origin is more useful for the language learner: it comes from the root путь (road) and the prefix рас- (like the English “dis”). In other words, to “disroad”!

11. авось

Although авось can be said to mean “maybe” (or more literally, “may be”), the word has a more in-depth meaning as well.

The concept of авось is more like a blind belief that things will work out. It represents the optimistic hope that luck will be on your side. You can use it as a strange mix of “hopefully” and “have faith”:

Авось Бог поможет. — Hopefully/I have faith that God will help.

Авось ты найдешь что ищешь. — Hopefully/I have faith that you’ll find what you’re looking for.

Надеемся на авось. — Let’s hope/put our faith in luck.

You can also use the phrase “на авось,” which is actually closest in translation to a well-known Spanish saying: “Que será, será” or “What will be, will be.”

12. встрепенуться

This wonderful word is similar to the English word “rouse,” as in “rouse yourself from sleep.” And “flutter,” as in “a bird fluttering its wings.” And “beat,” as in “a heart beating faster.” And…I’ll stop there.

So much meaning packed into one word! Although it’s mostly used in poetry, like in the timeless Russian poetry of Afanasy Fet (Афанасий Фет), this word is a perfect example of the versatile nature of the Russian language.

It comes from the root word трепет (thrill or awe), and is often used to refer to nature or humans (leaves can flutter and rouse themselves).

Another word with a similar concept is оживиться , which means to “liven up,” or, literally, to “bring life to yourself.”

13. грозный

You might not realize it, but you already know this word. Remember Ivan the Terrible? In Russian, he’s Иван Грозный !

Although it’s translated as “terrible,” грозный is closer in meaning to “threatening” or “overbearing.” The moniker wasn’t given to Ivan for his terrible deeds, but rather his fearsome nature.

The root of the word, гроз , means (loosely) “horror”—and is, incidentally, also the root of the word гроза (thunder)! Personally, I think Ivan the Thunderous is much more menacing.

14. совесть

We’re paying another visit to the mysterious Russian soul in this entry, with the word совесть—which is a sort of combination of conscience and morals, all rolled into one word.

Depending on the phrase, this word translates in slightly different ways to English:

имей совесть — “have some shame”

совесть имеешь? — “Do you have a moral compass?”

чистая совесть — “a clear conscience”

угрызения совести — “something eating at your conscience” (literally: “gnawings of conscience”)

But in a nutshell, совесть is the feeling of being expected to follow social morals, an intrinsic duty to have a conscience by human nature (rather than by law or through learning).

15. ударник

You might recognize the root this word derives from удар (a hit). Naturally, ударник can be used literally to mean drummer, the hammer of a gun or a hammer in general (and various other things related to hitting).

But in a broader sense, ударник is also a model worker, an upstanding employee who’s used as an example for other workers for how they should behave.

This word has historic origins, dating back to Soviet-era Russia to hyper-productive workers called “shock workers.” The idea was that by elevating hard workers to a position of national importance, other citizens would follow their example.

Although the word isn’t used often today in this sense, it’s an important part of Russian history, and you’ll still occasionally hear it live on through the phrase “ударный труд” (“shock work”), which refers to extremely hard or productive labor.

How to Learn Untranslatable Russian Words

There are plenty of ways to discover these wonderful Russian-specific words, but one of the best is by listening to Russian speakers do their thing. An immersion-based program like FluentU can help you with this.

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons. You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app. P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

You can also check out some helpful videos on YouTube, like this one:

As you learn more about the Russian language, you’ll get a deeper sense of the culture that birthed it. And after a while, the language’s idiosyncrasy will become second nature to you.

Good luck on your journey to fluency!

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

If you love learning Russian and want to immerse yourself with authentic materials from Russia, then I should also tell you more about FluentU.

FluentU naturally and gradually eases you into learning the Russian language and culture. You'll learn real Russian as it's spoken by real Russian people!

FluentU has a very broad range of contemporary videos. Just a quick look will give you an idea of the variety of Russian-language content available on FluentU:

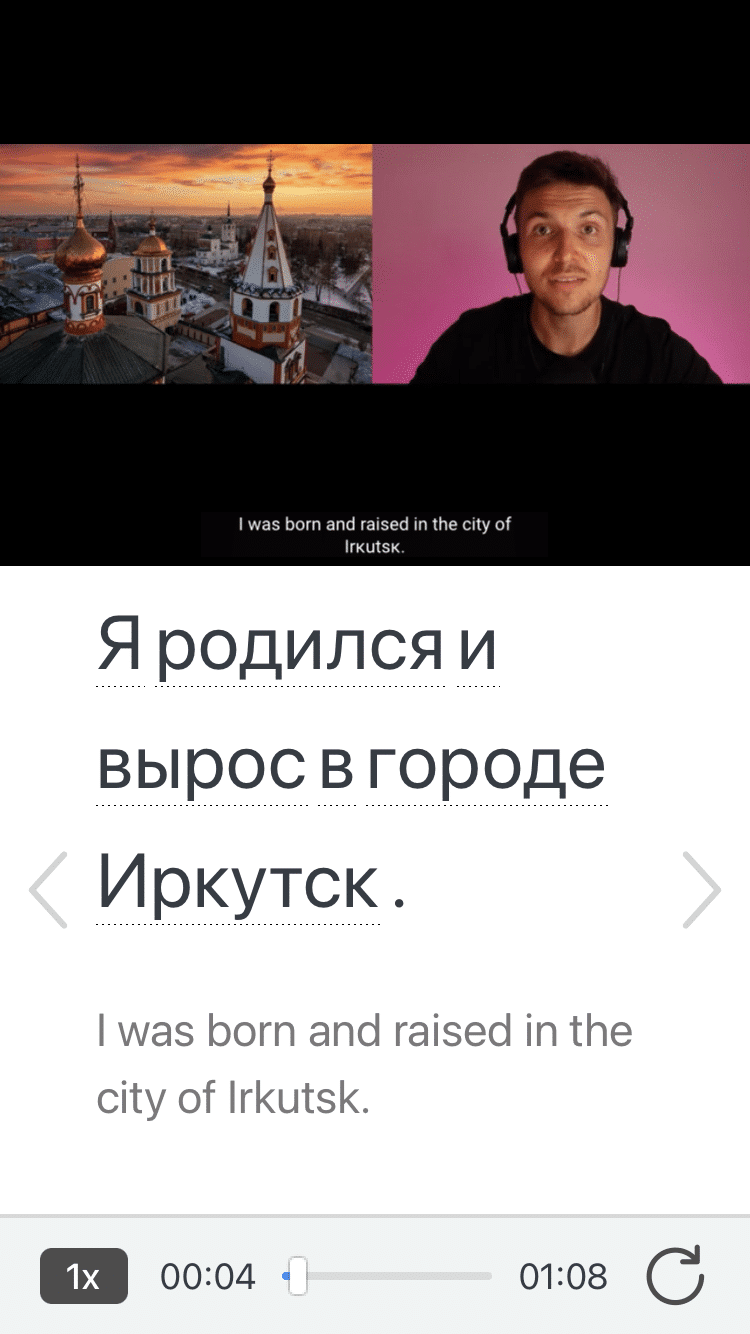

FluentU makes these native Russian videos approachable through interactive transcripts. Tap on any word to look it up instantly.

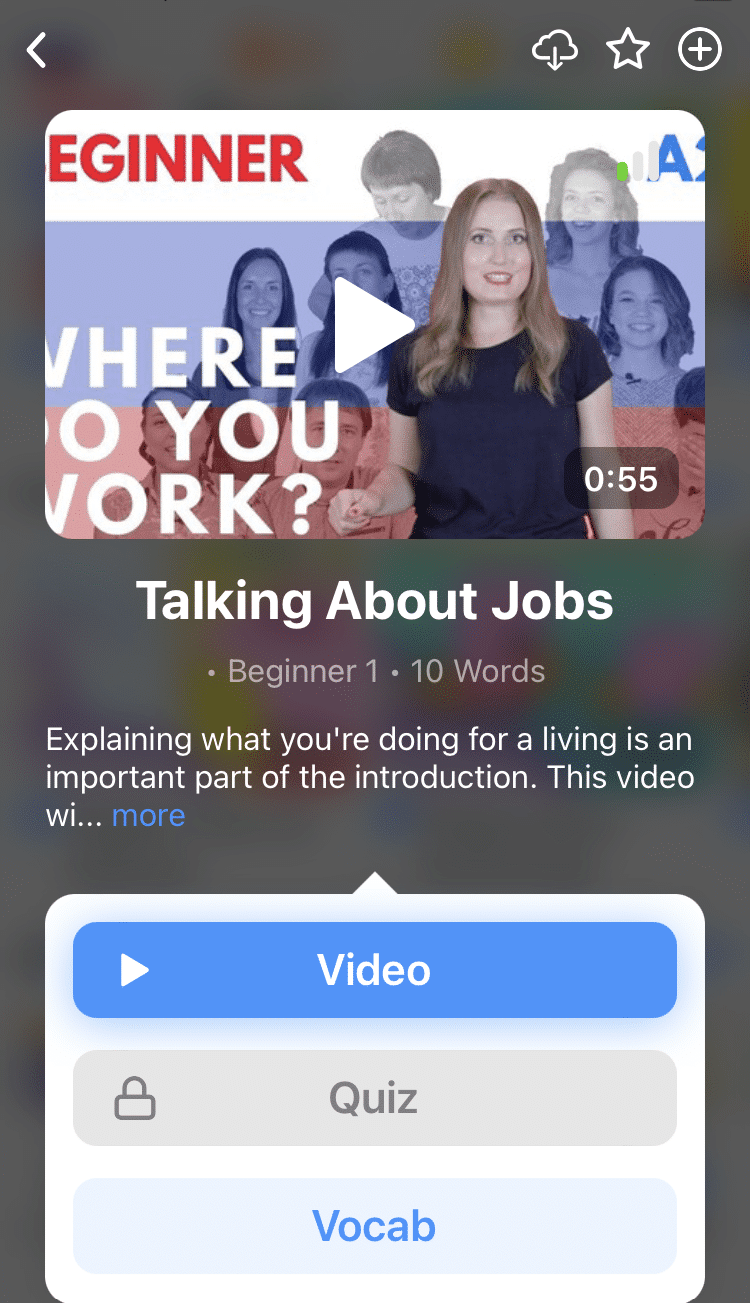

Access a complete interactive transcript of every video under the Dialogue tab. Easily review words and phrases with audio under Vocab.

All definitions have multiple examples, and they're written for Russian learners like you. Tap to add words you'd like to review to a vocab list.

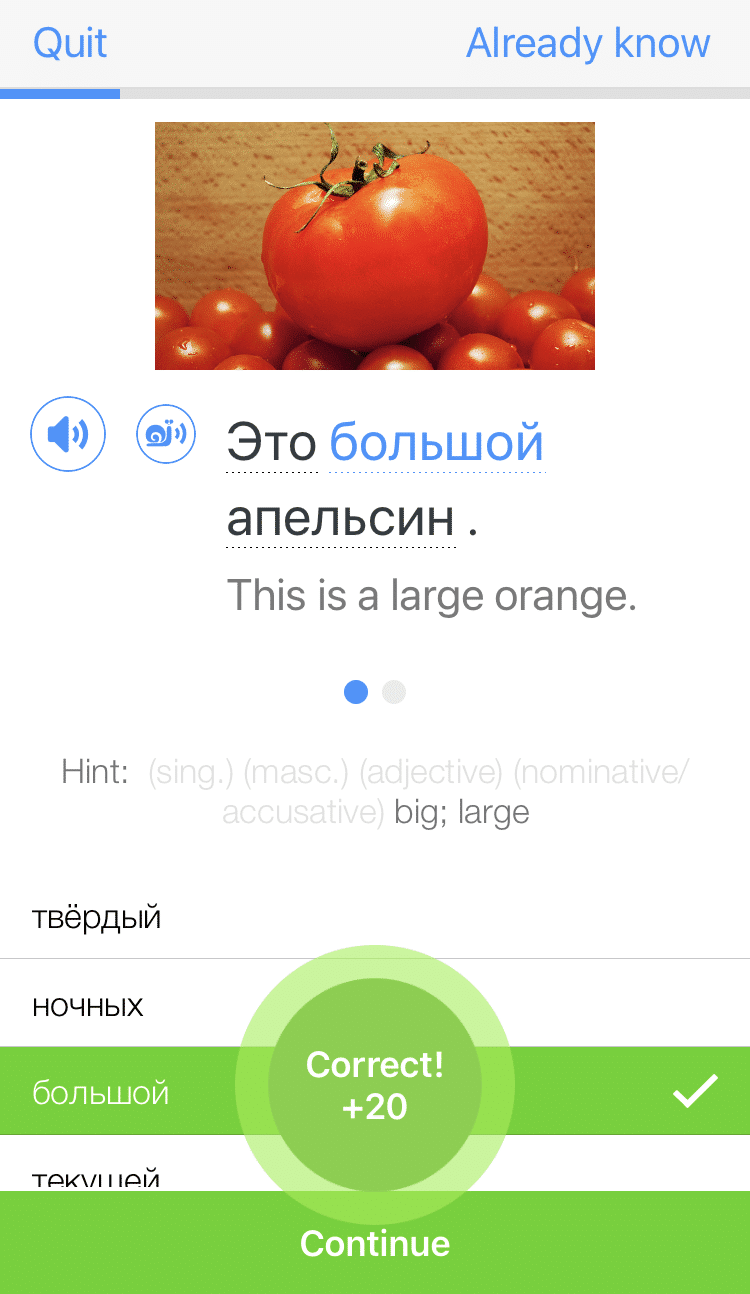

And FluentU has a learn mode which turns every video into a language learning lesson. You can always swipe left or right to see more examples.

The best part? FluentU keeps track of your vocabulary, and gives you extra practice with difficult words. It'll even remind you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. You'll have a 100% personalized experience.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

And One More Thing...