Brazilian Portuguese Grammar: 15 Essential Tips

If you’ve chosen to study Brazilian Portuguese, be aware that it’s slightly different from its European version.

But learning Brazilian Portuguese grammar doesn’t have to be intimidating.

Take a look at these 15 essential Brazilian Portuguese grammar rules covering everything from using personal pronouns to adjective placement.

Contents

- 1. Understand Brazilian Personal Pronouns

- 2. Master Brazilian Portuguese Articles

- 3. Get Your Genders Right

- 4. Learn the Difference Between Estar and Ser

- 5. Use the Gerund

- 6. Consider Gender with Demonstrative Pronouns

- 7. Make Note of Possessive Pronouns

- 8. Place Adjectives After the Noun

- 9. Remember Rules for Plurals

- 10. Start with the Simple Present Tense

- 11. Don’t Forget the Adverbs

- 12. Prepositions Matter, Too

- 13. Add Color to Your Speech with Interjections

- 14. Be More Natural with Contractions

- 15. It’s Okay to Use Negation

- Tips to Make Brazilian Portuguese Grammar Stick

- Portuguese Study Resources to Get You Started

- And One More Thing…

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

1. Understand Brazilian Personal Pronouns

One of the key differences between Brazilian and European Portuguese is the usage of personal pronouns. More specifically, it’s the Portuguese “you” that changes slightly according to dialect.

In Brazil, it’s more common to use você (third-person singular) to say “you,” whereas in Portugal tú (second-person singular) is the preferred form.

It’s important to mention that some parts of Brazil do use tú instead of você. But Brazilians often conjugate it the same way as they would when using você, in the third person. For example, they might say tú vai ao teatro for “you are going to the theater,” instead of the European Portuguese alternative, tú vais ao teatro.

Also, note that você in Brazilian Portuguese is informal; European speakers, on the other hand, view it as the formal “you.” To address someone who’s perhaps older or in a prestigious position (like your boss, a court judge or a customer you’re trying to please) Brazilians use o senhor (“you” masculine) or a senhora (“you” feminine).

In Brazil, a gente is also used as a general way of saying “us”—this is conjugated in the third person, just like você. Compare these two sentences, for example:

Você fez isso. — You did this.

A gente fez isso. — We did this.

As you can see, they’re both conjugated the same way.

Everything else is quite straightforward:

- Eu (I/me), ele (he), ela (she) are singular pronouns.

- Nós (we/us), vocês (you, informal), eles (they, masc.), elas (they, fem.) are plural pronouns.

- Os senhores (masc.) and as senhoras (fem.) are the pluralized versions of the formal “you.”

The Language Island offers a comprehensive guide to the different types of Portuguese pronouns, so you can learn all the equivalents of the English pronouns you already use.

You can read more about personal pronouns below:

Portuguese Pronouns (Personal Pronouns, Indefinite Pronouns and More) | FluentU Portuguese Blog

Master Portuguese pronouns once and for all! This comprehensive guide includes helpful tables for every single type of pronoun, from Portuguese personal pronouns to…

2. Master Brazilian Portuguese Articles

All articles in Portuguese must agree with the gender of the nouns they precede.

When using definite articles (i.e. articles that indicate something specific—like “the,” in English), masculine words are preceded by o; feminine words use the definite article a:

O homem — The man

A mulher — The woman

There’s also a plural form of “the”: os (masc.) and as (fem.):

Os homens — The men

As mulheres — The women

The same rule applies to indefinite articles (i.e. articles that indicate non-specific things):

Uma casa — A house (fem.)

In the above example, you can be talking about any house, not a specific one.

Um emprego — A job (masc.)

Again, this is quite general by nature. Any job will do.

When dealing with plural nouns, use uns (masc.) and umas (fem.):

Umas meninas — Some girls

Uns meninos — Some boys

Duolingo offers a guide to Portuguese articles. Not only can you read more about them, but you can also hear audio to help you get the pronunciation right. And if that’s not enough, you can even record yourself to compare your pronunciation with the examples given.

3. Get Your Genders Right

Usually, masculine nouns end in -o, while feminine ones end in -a:

A cadeira — The chair (fem.)

O carro — The car (masc.)

Similarly, feminine adjectives frequently end in -a, and masculine adjectives frequently end in -o. Vermelho/vermelha (red), gordo/gorda (fat), pequeno/pequena (small) are examples of gendered adjectives. They’ll agree with the noun they’re modifying.

There are, of course, a few exceptions:

| Exception | Examples |

|---|---|

| 1. Some words ending in -grama and -ema are masculine. | O programa — The program O sistema — The system O problema — The problem |

| 2. The word aroma (aroma) is one of a selected few that ends with -a but is masculine. | Um aroma — An aroma |

| 3. Gender can change the meaning of some words. | Um grama — One gram (masc.) Uma grama — A (blade of) grass (fem.) |

| 4. Words ending in -ão can be either masculine or feminine. | O coração — The heart O portão — The gate A mão — The hand A solução — The answer/solution |

| 5. Words ending with -e can be either masculine or feminine. | Uma semente — A seed (fem.) A lente — The lens (fem.) O pingente — The pendant (masc.) Os dentes — The teeth (masc. plural) |

| 6. Nouns ending in -ade and -gem are usually feminine. | A idade — The age Uma viagem — A trip |

A few adjectives, such as cinza (gray), marrom (brown) and violeta (violet) are gender-neutral. They won’t change their form no matter what noun they’re describing.

To take a closer look at all these rules in action, StreetSmart Brazil lists a handful of commonly used words you’ll want to add to your vocabulary list. If you’ve ever dabbled in Spanish, this post also compares some of the gender differences between both languages.

You could also try out the exercises on Unilang. The exercises ask you to translate both to and from Portuguese, so you’ll also have to learn a little vocabulary along the way.

Finally, Rio & Learn offers a very detailed breakdown of different noun endings and how they tie into the word’s gender. At the bottom of the page, there’s also a very helpful exercise that asks you to change the gender in the sentence, which is a good way to get more comfortable with this grammar topic.

4. Learn the Difference Between Estar and Ser

Portuguese has two forms of the verb “to be,” both of which are irregular.

Estar is the form you’d use when talking about a location, or other changeable characteristics:

Ser is the physical act of being—in other words, the things you can’t really change:

Aside from ser and estar, you’ll also want to know ter / haver (to have) and fazer (to do), since these show up quite often.

5. Use the Gerund

One of the key differences between Brazilian and European Portuguese verb conjugation is the use of the gerund (that’s the -ing form of a verb in English).

Brazilian speakers always use the gerund to describe an action that’s taking place:

Estou trabalhando. — I am working.

Meanwhile, the European Portuguese dialect favors a different form of saying the same thing:

Estou a trabalhar. — I am working.

Above, the infinitive form of the verb “to work” (trabalhar) is used instead of the gerund.

Here are a few more examples:

| Brazilian Portuguese | European Portuguese | English translation |

|---|---|---|

| Estou falando | Estou a falar | I am speaking. |

| Ele está fazendo | Ele está a fazer | He is doing. |

| Está chovendo | Está a chover | It is raining. |

Forming the gerund in Portuguese is relatively simple. The rules are consistent with verb endings, regardless of whether you’re dealing with regular or irregular verbs.

First, you need to take the present tense of the verb estar and add the verb that’s going to have the gerund ending added to it.

| Type of verb | Gerund | Example verbs | Example sentences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Verbs ending in -ar | -ando | falar (to speak) chegar (to arrive) chamar (to call) | Ele/ela está falando. — He/she is speaking. Eu estou chegando. — I am arriving. Nós estamos chamando. — We are calling. |

| Verbs ending in -er | -endo | dizer (to say) comer (to eat) ser* (to be) | Ele/ela está dizendo. — He/she is saying. Nós estamos comendo. — We are eating. Você está sendo difícil. — You are being very difficult. |

| Verbs ending in -ir | -indo | fugir (to run away, to flee) dirigir (to drive) corrigir (to correct) | Você está fugindo. — You are running away/fleeing. Eu estou dirigindo. — I am driving. Nós estamos corrigindo. — We are correcting. |

*Note that ser is an irregular verb.

And if you’ve ever crossed paths with the irregular verb ir (to go), you’re in luck: It follows the exact same gerund rule as other -ir verbs.

Eu estou indo. — I am going.

Você está indo. — You are going.

Nós estamos indo. — We are going.

6. Consider Gender with Demonstrative Pronouns

As with everything that precedes a noun, a demonstrative pronoun must agree with the gender of the word it’s talking about.

The Portuguese demonstrative pronouns are:

| English | Masculine | Feminine | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| This | Este | Esta | Este homem — This man Esta mulher — This woman |

| That | Esse | Essa | Esse menino — That boy Essa menina — That girl |

| These | Estes | Estas | Estes meninos — These boys Estas meninas — These girls |

| Those | Esses | Essas | Esses homens — Those men Essas mulheres — Those women |

Here are a few examples of how these are used in everyday phrases:

7. Make Note of Possessive Pronouns

Portuguese possessive pronouns have feminine, masculine, singular and plural forms:

| English | Masculine | Feminine |

|---|---|---|

| My/mine | Meu (singular) Meus (plural) | Minha (singular) Minhas (plural) |

| Your/yours | Seu (singular) Seus (plural) | Sua (singular) Suas (plural) |

| His/hers | Dele | Dela |

| Theirs | Deles (plural) | Delas (plural) |

| Our/ours | Nosso (singular) Nossos (plural) | Nossa (singular) Nossas (plural) |

Here are a few examples of how these might be used:

8. Place Adjectives After the Noun

Like English, Portuguese follows the subject-verb-object (SVO) sentence structure. The main difference is in the adjective placement. For example, you have something like:

A criança feliz gosta de seus presentes.

The happy child enjoys his presents.

Literal translation: The child happy enjoys his presents.

As you can see, the describing word usually follows its subject. Here are a few more examples:

Um livro interessante — An interesting book (livro — book; interessante — interesting)

Essa camisa azul — That blue shirt (camisa — shirt; azul — blue)

A menina criativa — The creative girl (menina — girl; criativa — creative)

While most adjectives have to agree in gender with their modified nouns, there are some that remain unchanged:

Um homem inteligente / Uma mulher inteligente — An intelligent man/An intelligent woman

Um menino forte / Uma menina forte — A strong boy/A strong girl

O diretor idealista / A diretora idealista — The idealist director/principal (diretor is masculine; diretora is feminine)

Meu amigo comunista / Minha amiga comunista — My communist friend (amigo is a masculine “friend”; amiga is a feminine “friend”)

Brazilians call these adjetivos uniformes (uniform adjectives). If you have a dictionary handy, take a look at a list of uniform adjectives devised for native speakers.

That said, there are always exceptions to the rule, so you can definitely find instances where native speakers put the adjective first:

- Mal/má (bad), grande (big) and bom/boa (good) are the most common adjectives you may see in front of nouns, and their placement there can even change the meaning of the sentence. For example, when placed before the noun, grande often means “great” but when placed after the noun, it’s more likely to mean “big.”

- Similarly, the placement of bom/boa can dramatically change a sentence’s meaning. For instance, “ela é uma mulher boa” will be perceived as “she’s a good woman.” However, “ela é uma boa mulher” might be understood as “she’s a hot woman.”

If you’re looking for places to practice adjective placement and Portuguese word order in general, check out this guide from Learn Portuguese with Rafa. You could also take advantage of the word order activities on the gamified language learning app Duolingo.

9. Remember Rules for Plurals

Like in English, some Portuguese nouns can be pluralized by simply adding -s at the end. However, other words have more complicated pluralization rules.

Here are some general guidelines:

| Word Ending | Pluralization Rule | Example |

|---|---|---|

| -a, -e, -i, -o or -u | Add -s | garfo (fork) -> garfos (forks) |

| -al, -el*, -ol* or -ul | Replace the -l with an -is *Words that end in -el or -ol require an accent over -e or -o, respectively | animal (animal) -> animais (animals) |

| -il | Replace the -l with an -s | barril (barrel) -> barris (barrels) |

| -em | Replace the -m with an -ns | homem (man) -> homens (men) |

| -r, -s or -z | Add -es | luz (light) -> luzes (lights) |

| -ão | Change the ending to -ões, -ães or -ãos *No standard rules for these, unfortunately. You need to memorize specific pluralization rules for different -ão words | avião (airplane) -> aviões (airplanes) pão (bread) -> pães (breads) mão (hand) -> mãos (hands) |

Additionally, once you’ve pluralized nouns, you’ll also need to pluralize any adjectives you use to match those nouns. Adjectives follow the same basic pluralization rules as nouns. For instance, azul (blue) becomes azuis (blues) in the plural form.

You can find a comprehensive guide to pluralizing nouns here, where there are also tons of examples showing how different word endings can affect the way a noun is pluralized.

And if you think your pluralization skills are up to snuff, try out this fun Quia quiz that you can play solo or with a friend. The setup is a lot like Jeopardy: Pick a category, get a word to pluralize and score points for every correct answer.

10. Start with the Simple Present Tense

If you’re just starting on Portuguese verb conjugations, try to focus on the simple present tense first. That way, even if you aren’t being 100% grammatically correct, you can still get your point across.

As mentioned earlier, Portuguese verbs end in -ar, -er or -ir. How you conjugate them depends on the ending. Let’s look at one set of simple present tense conjugations for each type of verb ending:

| Pronoun | -ar Verb: Falar (To Speak) | -er Verb: Dever (To Owe; Used Like “Should”) | -ir Verb: Existir (To Exist) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eu | falo | devo | existo |

| Você/Ele/Ela | fala | deve | existe |

| Nós | falamos | devemos | existimos |

| Vocês/Eles/Elas | falam | devem | existem |

It’s important that you really nail down basic verb tenses before you move on to some of the more complex constructions.

Plus, in all of the tenses, there are also some irregular verbs, the most common of which can be found at ielanguages.com and learningportuguese.co.uk.

And if you need more Portuguese verb conjugation practice, you can head over to Conjuguemos, which is chock-full of exercises and activities. Likewise, ListeningPractice.org presents dozens of ways to conjugate Portuguese verbs according to frequency, tense, number and person.

Here’s a little more about Portuguese conjugations:

How to Conjugate Portuguese Verbs | FluentU Portuguese Blog

Portuguese verb conjugation doesn’t have to be complicated. In fact, you can master it in just 4 simple steps. Click here to learn the ins and outs of Portuguese verb…

11. Don’t Forget the Adverbs

Similar to their English counterparts, Portuguese adverbs modify verbs, adjectives or other adverbs, typically answering questions like “how,” “at what time” and “to what degree.”

Let’s take rapidamente (quickly, rapidly), for example:

When a modifying word has the suffix -mente, there’s usually a good chance that the word is an adverb. Think of it as the equivalent to the English -ly.

Of course, not all Portuguese adverbs end in -mente. Take a look at these:

Aqui — Here

Menos — Less/Minus

Quando — When

12. Prepositions Matter, Too

Portuguese prepositions show the relationship between objects in time and space. They include words like:

Desde — Since

Antes — Before

Sem — Without

For more on Portuguese prepositions, read this post:

37 Common Portuguese Prepositions and Contracted Prepositions | FluentU Portuguese Blog

Learn Portuguese prepositions with this guide to the most common prepositions in the language. Learn their meanings, see them in use and learn all about preposition…

13. Add Color to Your Speech with Interjections

Also called exclamations, Portuguese interjections are used to communicate emotion, as in:

Ai — Ouch

Hein — Huh

Graças a Deus — Thank God

Although interjections aren’t necessary to be grammatically correct, they can make you sound more like a native speaker when you use them.

14. Be More Natural with Contractions

Just as English has words like “can’t” or “they’re,” Portuguese often merges words. Unlike English, where contractions are often optional, many Portuguese contractions are necessary to be grammatically correct.

Some Portuguese examples include:

Num/numa — In/On some

Destes/destas — Of these

Nos/Nas — On the

Find more Portuguese contractions here:

166 Portuguese Abbreviations, Acronyms and Contractions | FluentU Portuguese Blog

No one wants to write out full words and names. Use a Portuguese abbreviation, instead! Learn Portuguese abbreviations, acronyms and contractions for everything from text…

15. It’s Okay to Use Negation

Forming negative sentences in Portuguese is pretty straightforward. Just tack on a negative word like não (not) or nunca (never) in front of the verb that isn’t being done:

Tips to Make Brazilian Portuguese Grammar Stick

Personalizing your studies is the best way to tackle complex topics like grammar.

Take this as your cue to mix and match various study strategies and resources—you’ll only know what works best by experimenting with different learning styles.

Here are few ideas you can try:

Make use of other learning media

Still in the technology realm, open online courses (called MOOCs), educational podcasts and online video classes will also teach you those essential grammar rules. They can also help you put them in context with practice drills and examples of daily usage.

Go Offline

Of course, you shouldn’t neglect the traditional approaches. Consider investing in a good grammar textbook and/or workbook so that you can nail the theory side of things. If you need help finding one, hang tight—that’s a point I’ll be covering soon.

Don’t forget to jot things down in a notebook as you go—and definitely spend some time working on constructing some sentences. Not only will this help you remember the concepts you’ve been learning, it’ll also add some much-needed Brazilian Portuguese spelling practice into the mix.

Apply the rules to real-life examples

Lastly, as you get more confident, take note of how different grammar rules apply to the things you’ve been reading, listening to and watching (whether it’s movies, TV dramas or even cooking shows).

If you’d like some extra language learning support while immersing yourself in the language, you could try using FluentU. This language learning program has an array of authentic Brazilian Portuguese videos like inspiring talks and music videos. Each video is accompanied by interactive subtitles that you can use to quickly find the meaning of a word or see more examples of a term in use.

Context is key, after all, and content coming straight from native Brazilian speakers is sure to make things more interesting—and more authentic.

Portuguese Study Resources to Get You Started

Need a hand finding some good study aides? Don’t worry, I’m here to help you out!

For a well-rounded reference guide, try “Modern Brazilian Portuguese Grammar: A Practical Guide.” Divided into two parts, this book covers all the traditional rules beginner to advanced learners need to know by illustrating them with practical examples of how they’re used in contemporary Brazil. Check out the accompanying workbook if you want to put these conventions into practice.

If you need to brush up on your verbs, take a look at “501 Portuguese Verbs.” This reference guide features some of the most commonly used Portuguese verbs, with their respective English translations, conjugated in all persons and tenses.

It also includes language tips like idiomatic expressions, useful travel phrases and a few practice exercises to help you commit all this bookish knowledge to memory.

You can also check out these online grammar exercises:

15 Portuguese Grammar Exercise Resources | FluentU Portuguese Blog

Portuguese grammar exercises can help you sharpen your “gramática” (grammar) no matter your level. Check out these resources for ensuring that you get things like…

That’s all for now! Take your time learning the above rules—we’ve covered a lot of ground. As you look closer into each of these conventions, others I haven’t included in this post will likely come up.

Keep practicing, studying and noting things as you go. You’ll become a Brazilian Portuguese grammar pro before you know it!

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing…

If you've made it this far that means you probably enjoy learning Portuguese with engaging material and will then love FluentU.

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized Portuguese lessons.

Other sites use scripted content. FluentU uses a natural approach that helps you ease into the Portuguese language and culture over time. You’ll learn Portuguese as it’s actually spoken by real people.

FluentU has a wide variety of videos, as you can see here:

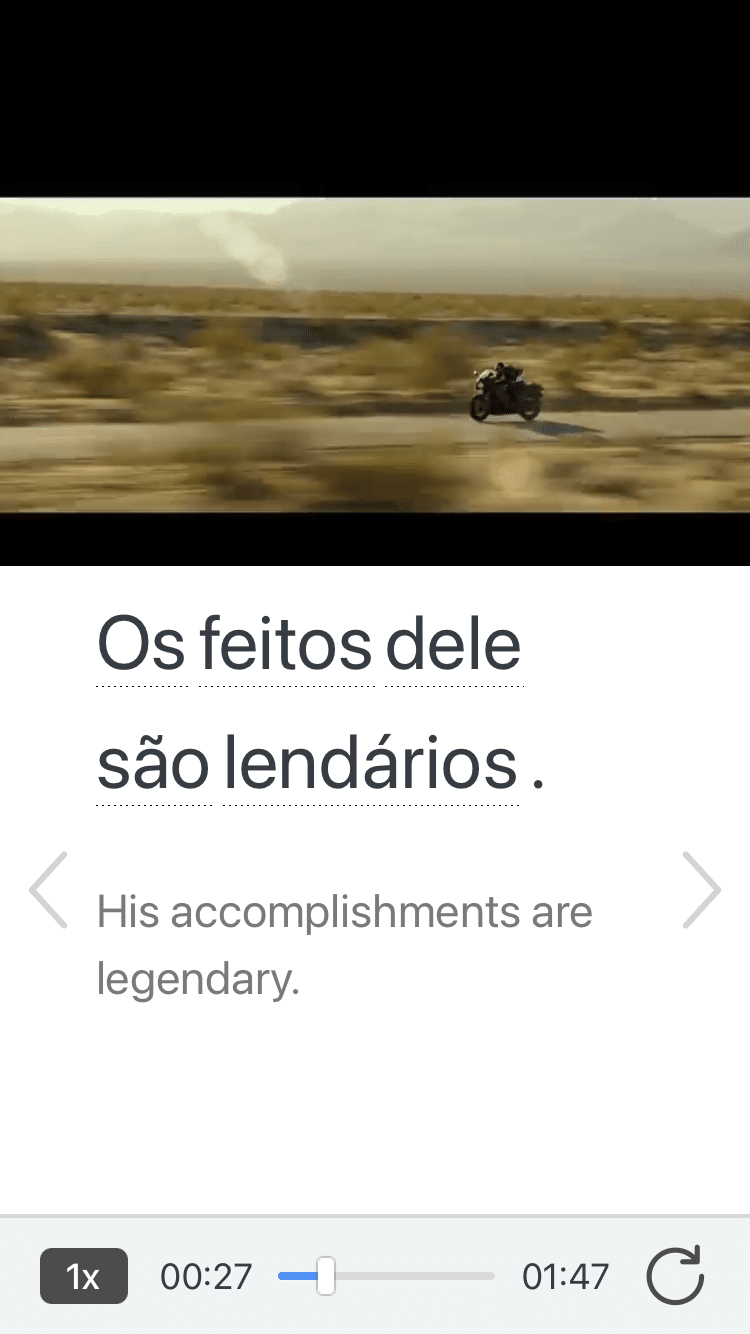

FluentU brings native videos within reach with interactive transcripts. You can tap on any word to look it up instantly. Every definition has examples that have been written to help you understand how the word is used. If you see an interesting word you don’t know, you can add it to a vocab list.

Review a complete interactive transcript under the Dialogue tab, and find words and phrases listed under Vocab.

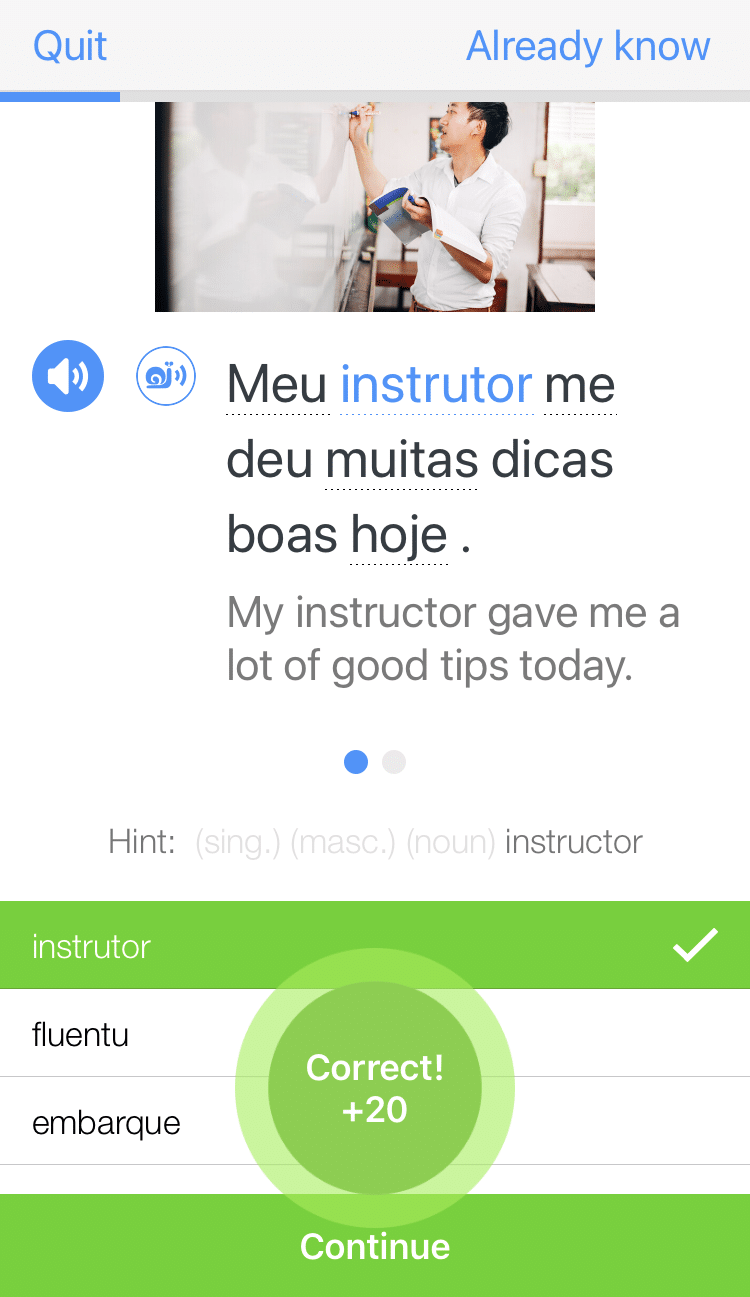

Learn all the vocabulary in any video with FluentU’s robust learning engine. Swipe left or right to see more examples of the word you’re on.

The best part is that FluentU keeps track of the vocabulary that you’re learning, and gives you extra practice with difficult words. It'll even remind you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. Every learner has a truly personalized experience, even if they’re learning with the same video.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Click here to check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.