23 ESL Speaking Activities for Adults

ESL class is the perfect place to make English mistakes. But speaking out loud in front of other people—especially in a second language—can be nerve-wracking for many adults.

Keep reading to find out all you need to know about ESL activities for adults.

Contents

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

ESL Games

1. Alibi

This well-known ESL game is great speaking practice for adults. The teacher tells the class that a particular crime has been committed. For fun, make it locally specific. For example:

“Last Friday night, sometime between ___ and ___, someone broke into the ____ Bank on ____ Street.”

Depending on the size of your class, pick several students as “Suspects.” The “Police” can work in groups of 2-4, and you need one Suspect for each police group. So, for example, in a class of 20 you could choose four Suspects and then have four groups of four Police for questioning.

Tell the class: “___, ___, ___ and ___ were seen near the scene of the crime, and the police would like to question them.”

The Suspects go outside or to another room to prepare their story. They need to decide all of the details about where they were during the time of the crime. For example: If they were at a restaurant, what did they eat? What did it cost? Who arrived first?

1. The Police spend some time preparing their questions.

2. The Suspects are called back in and go individually to each police group. They’re questioned for a few minutes, and then each one moves on to the next group.

3. The Police decide whether their answers match enough for them to have a reasonable Alibi. (Maybe up to five mistakes is reasonable.)

2. Bingo

Many people think of this game as a listening activity, but it can very quickly become a speaking activity.

There are a number of ESL websites that will allow you to quickly create a set of Bingo cards containing up to 25 words, phrases or even whole sentences. They’ll allow you to make as many unique cards as you need to distribute a different card to each student in the class. Each card can contain the same set of words arranged differently, or you can choose to have more or less than 25 items involved.

Rather than having students mark up their cards, you can give them markers (such as stones or sunflower seeds) to place on each square as they recognize it. This way the markers can be removed and the game can be repeated.

For the first round, the teacher should “call” the game. The first student to get five markers in a row in any direction shouts out “Bingo!” Then you should have this student read out every item in their winning row.

The winner is congratulated and then rewarded by becoming the next Caller. This is a great speaking opportunity. Everyone removes their markers and the game starts again. Every expression that’s called tends to be repeated quietly by everyone in the room, and by the end of a session, everyone can say all of the expressions on the card.

3. Taboo

In this game, one player has a card listing four words:

- The first word is the secret word. The aim of the game is to get another player to say this word. The student with the card will need to describe this word until another student figures out the secret word.

- The other three words are the most obvious words that you might use to explain the secret word. They are all “taboo” and cannot be used in the student’s description of the secret word.

This game can be played between two teams. It can also be played between partners. You can create your own sets of words based on what you’ve been studying, or you can find sets in your textbook and on the internet.

Taboo is great for challenging students to expand on the vocabulary they would usually use, and helps them to think outside of the box. You can try timing them for an extra challenging element, or even play it as a whole class to get everyone involved in trying to guess the word on the card.

Students will have great fun playing, while also improving their speaking and communication skills, making it an ideal ESL game.

4. I Like People

Adults do like to have fun, as long as they aren’t made to feel or look stupid. This is a brilliant game for helping them think quickly and speak more fluent English (rather than trying to translate from their native tongue).

1. Students sit on chairs in a circle, leaving a space in the circle for the teacher to stand.

2. First, they’re asked to listen to statements that the teacher makes and stand if it applies to them, such as: “I like people who are wearing black shoes,” “I like people who have long hair,” etc.

3. Next, the teacher asks standing students to change places with someone else who’s standing.

4. Now it becomes a game. The teacher makes a statement, students referred to must stand and quickly swap places. When the students move around, the teacher quickly sits in someone’s spot, forcing them to become the teacher.

5. The students quickly get into the swing of this game. Generally, they’ll quickly notice a “cheating” classmate who hasn’t stood up when they should have, and they’ll also eagerly encourage a shy student who finds himself standing in the gap with no ideas.

This game has no natural ending, so keep an eye on the mood of the students as they play. They may start to run out of ideas, making the game lag. Quickly stand and place yourself back into the teacher position and debrief (talk with them about how they felt about the game).

5. Sentence Auction

Create a list of sentences, some correct and some with errors.

- The errors should be related to a language topic you’re teaching

- The number of sentences will depend on your students’ abilities. 20 is a good number for intermediate students.

- The ratio of correct and incorrect is up to you, but it’s a good idea to have more than 50% correct.

Next to the list of sentences draw three columns: Bid, win, lose.

You can set a limit for how much (imaginary) money they have to spend, or just let them have as much as they want.

They need to discuss (in English) and decide whether any sentence is 100% reliable, in which case they can bid 100 dollars (or whatever unit you choose). If they’re totally sure that it’s incorrect, they can put a “0” bid. If they’re unsure, they can bid 20, 30, 40, based on how likely it is to be correct.

- When all of their bids are written in, get pairs to swap their papers with other pairs for marking.

- Go through the sentences, discussing which are correct and why.

- For correct sentences, the bid amount is written in the “win” column. For incorrect sentences, it’s written in the “lose” column.

- Both columns are totaled, and the “lose” total is subtracted from the “win” total.

- Papers are returned, and partners discuss (in English) how their bidding went.

6. Typhoon

This game can be played with a class as small as three, but it also works with large classes.

1. On the board draw a grid of boxes (e.g. 6 x 6). Mark one axis with numbers, the other with letters.

2. On a piece of paper or in a notebook (out of sight) draw the same grid. On your grid, fill in scores in all of the boxes. Most of them should be numbers, and others will be letters. It doesn’t matter which numbers you choose, but it’s fun to have some small ones (1, 2, 3, etc.) and some very big ones (500, 1000, etc.). About one in four boxes should have the letter “T” for “Typhoon.”

3. Mark a place on the board to record each team’s score.

4. Ask questions to each team. If they answer correctly, they “choose a box” using the grid labels. The teacher checks the secret grid, and writes the score into the grid on the board. This score also goes into the team’s score box.

5. If the chosen box contains a number, the scores simply add up. But if the box contains a “T,” the team then chooses which other team’s score they want to “blow away” back to zero.

You can spice it up by adding different symbols in some of the boxes. I use:

- Swap: They must swap their score with another team’s score.

- S: Steal. They can steal a score.

- D: Double. They double their own score.

Here’s an example of one Typhoon variation:

7. Improv

1. Devise several scenarios with two or more characters and a premise. These could be something simple, like someone going to a bakery to buy a cake or visiting a museum with an unusual exhibit.

2. Divide your students into teams, with one student per role.

3. Give your students the premise for the scenario they’re going to act out. For example, you might say, “You’re a father at a bakery, trying to buy a cake with your child’s favorite cartoon character. The baker has never heard of this character. You need to describe how the character looks so that the baker can create the cake you want.”

4. Each team member will have about five minutes to prepare their part of the skit. Ask each student to prepare separately. That way, the other students they are interacting with must react spontaneously to their questions and statements.

5. Each team will perform their vignette in front of the whole class. Limit the time to play out each scenario to five or ten minutes.

6. At the end of each round, the non-performing class members can ask questions of those performing their roles. The performing students should respond in character to the questions.

This activity will help students react to impromptu situations.

8. News Brief

Prepare a number of short news stories for different students to read. You can use stories directly from a source like:

- The Times in Plain English

- Breaking News English

- News in Levels

- FluentU (Each video on FluentU has transcripts, so you can let your students read the transcripts as an alternative to watching the clip.)

1. Divide the class into teams of four or five students. Each team will read one of the short news stories you’ve prepared.

2. One student on the team will pretend to be a news anchor reporting on the story. Another student can play a field reporter, who will interview the remaining students. The remaining students can play either passers-by or eyewitnesses to an incident.

3. You can prepare multiple stories for each team. With each new story, students should exchange roles, so that they each have a chance to practice different kinds of speaking.

Students playing the “eyewitnesses” will get the opportunity to answer spontaneously, especially if they’re not privy to the reporter’s questions ahead of time. The news anchor and reporter roles will require more formal, neutral English.

The interviewees will also have more opportunities to practice speech that expresses emotion, since they’ll be communicating their opinion on a hot topic.

Variation:

To stretch out this activity into multiple lessons, consider assigning your students a writing exercise in which they “manufacture” their own news stories.

These news stories can have a humorous angle which could afford students the opportunity to explore satire using English.

9. Running Dictation

This useful activity requires students to use all four language skills—reading, writing, listening, and speaking—and if carefully planned and well-controlled can cause both great excitement and exceptional learning.

Pair students up. Choose who will run and who will write. (At a later stage they could swap tasks.)

Print out some short texts (related to what you’re studying) and stick them on a wall away from the desks. You should stick them somewhere out of sight from where the students sit, such as out in the corridor.

There could be several numbered texts, and the students could be asked to collect two or three each. The texts could include blanks that they need to fill in later, or they could be asked to put them in order. There are many possibilities here!

The running students run (or power-walk) to their assigned texts, read, remember as much as they can and then return to dictate the text to the writing student. Then they run again. The first pair to finish writing the complete, correct texts wins.

Be careful that you do not:

- Let students use their phone cameras to “remember” the text.

- Let “running” students write—they can spell words out and tell their partner when they’re wrong.

- Let “writing” students go and look at the text (or let “running” students bring it to them).

ESL Discussion Activities

10. Surveys and Interviews

Becoming competent at asking and answering questions is invaluable in language learning. It is helpful in a range of contexts, including anything from speaking exams, to casual conversation.

In the simplest form of classroom survey practice, the teacher hands out ready-made questions—maybe 3 for each student—around a topic that is being studied.

For example, let’s say the topic is food. Each student could be given the same questions, or there could be several different sets of questions such as questions about favorite foods, fast foods, breakfasts, restaurants, home-style cooking, etc.

Then each student partners with several others (however many is required), and asks them the questions on the paper. In each interaction, the student asking the questions will note down the responses from their peers.

At the end of the session, students may be asked to stand up and summarize what they found out from their survey. This helps them to consolidate a range of opinions based on the same topics. You can change the difficulty of the topics based on the level of your students, and center it around what you are focusing on in lessons.

This makes it a great exercise to use for all your classes and is easily customizable based on the needs of your students.

11. Show and Tell

Students can be asked to bring to school an object to show and tell about. This can be anything from a favorite item of clothing, to a souvenir they picked up on an interesting trip. This is lots of fun because students will often bring in something that’s meaningful to them or which gives them pride. That means they’ll have plenty to talk about! Encourage students to ask questions about each other’s objects.

Instead of having students bring their own objects, you could provide an object of your own and ask them to try to explain what they think it is and what its purpose is. Another option is to bring in pictures for them to talk about. This could be discussed with a partner or in a group, before presenting ideas in front of the whole class.

Generate a stronger discussion and keep things flowing by asking students open-ended questions. Speaking for an extended period about one object will help students challenge themselves to say different, and more creative things. The exercise can also be easily repeated by asking students to bring in different objects the next time, or by providing a selection of your own objects to inspire them.

12. Short Talks

Create a stack of topic cards for your students, so that each student will have their own card.

Each student draws their card, and then you assign them a time limit—this limit may be one minute initially, or maybe three minutes when they have had practice. This is the amount of time that they’ll have to speak about their given topic.

Now, give the students a good chunk of time to gather their thoughts. You may want to give them anywhere from five minutes to half an hour for this preparation stage. You can let them write down three to five sentences on a flashcard to remind them of the direction they’ll take in the course of their talk.

To keep listening students focused, you could create an instant “Bingo” game. The class is told the topic and asked to write down five words that they might expect to hear (other than common words such as articles, conjunctions and auxiliary verbs). They listen for those words, crossing them off as they hear them and politely raising a hand if they hear all five.

You can adjust the complexity of the task depending on your students, and gradually increase the difficulty if you play more regularly to ensure you are stretching their skills.

13. Video Dictionary

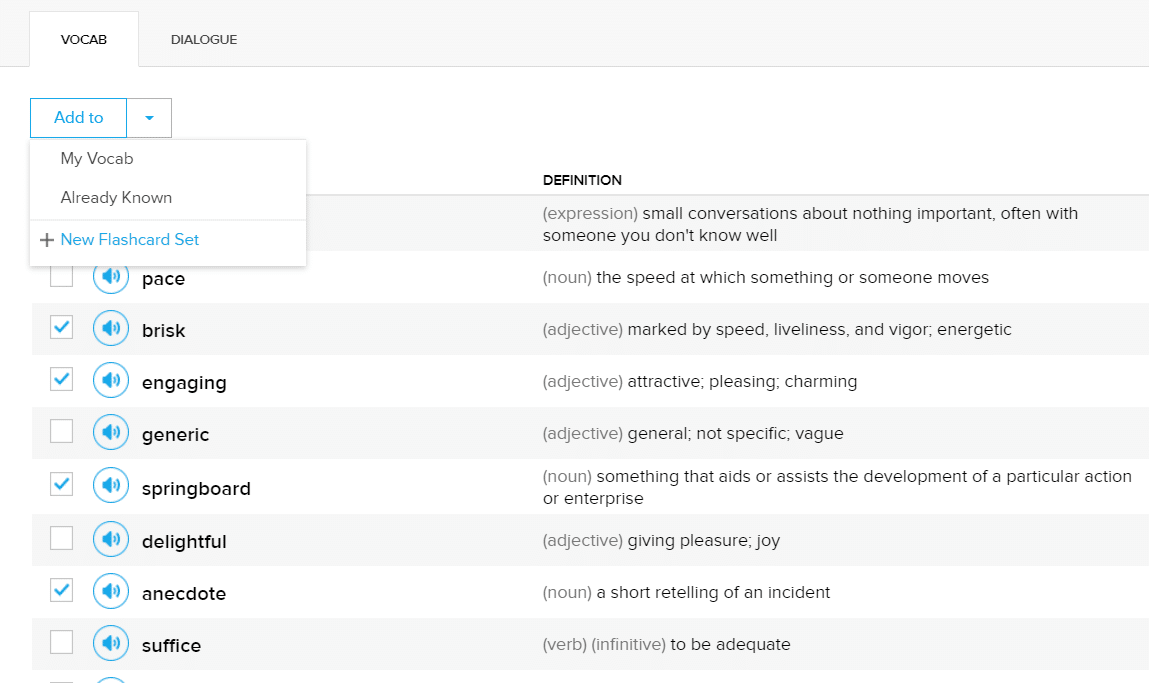

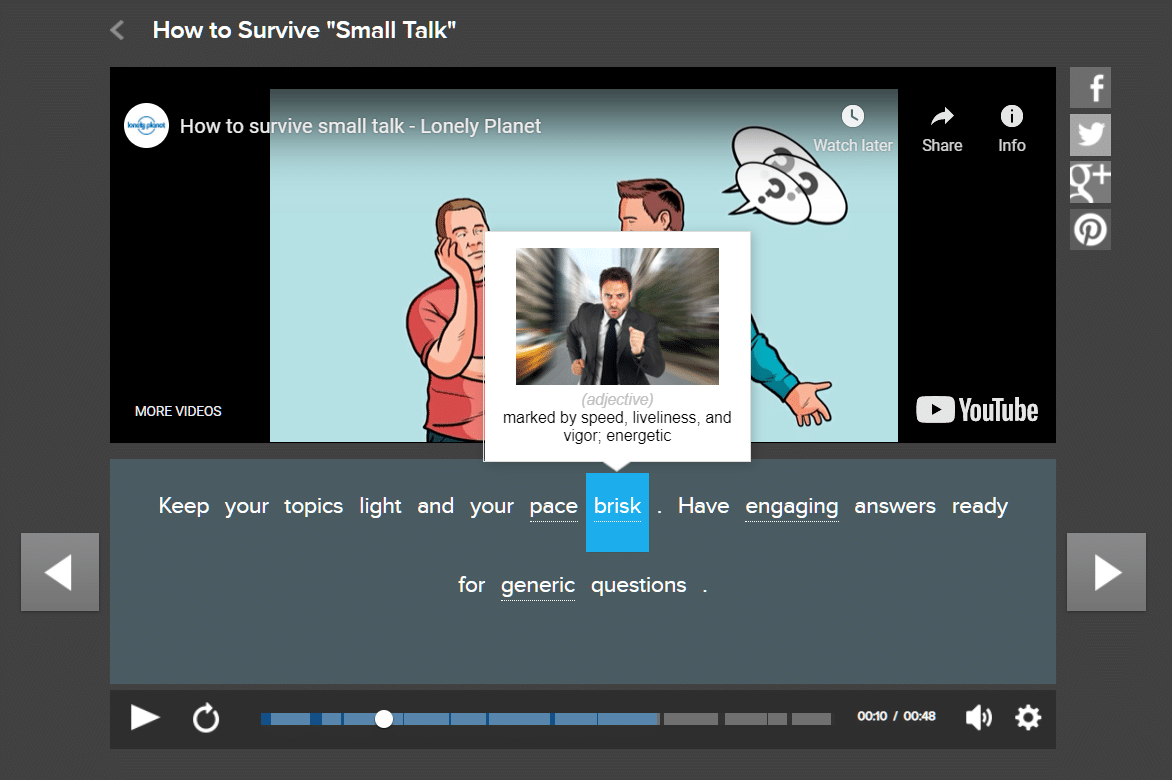

The authentic English videos on FluentU—with its built-in vocabulary lists—can be catalysts for conversation practice. Every word used in a video has a definition, plus extra usage examples.

In this activity, students will learn some vocabulary words from the videos, then create their own definitions or usage examples for those words.

Select several FluentU videos for teams of your students to watch, according to their level. Then, You can then use the built-in vocabulary list to select the words you’d like your students to learn.

In the example below, you might target certain words in the Vocab list, such as “anecdote,” “engaging” and “brisk.”

Divide your class up into teams of about three or four students apiece and have them watch the selected videos. Students will work together to come up with new usage examples or definitions to illustrate the vocabulary words from their chosen video

Teams will then take turns presenting words (and their own examples or definitions) to each other. Students on each team should take turns presenting their example sentences or definitions.

Students can also be given time for discussing the words they learn, having conversations about what the words mean and how to use them.

After watching the other teams’ presentations, students who didn’t watch the video can take the accompanying quiz on FluentU, to see how well they learned the target words from their fellow students.

14. PechaKucha

If your students have laptops (or a computer lab they can use) and are reasonably familiar with presentation software (such as PowerPoint), then all that’s left to acquire for this activity is access to an LCD projector.

Students can have a lot of fun speaking while giving a presentation to the class. Using projected images helps to distract some attention away from the speaker and can be helpful for shy students.

The “PechaKucha” style of presentation* can give added interest with each student being allowed to show 20 slides only for 20 seconds each (the timing being controlled by the software so that the slides change automatically) or whatever time limit you choose. You could make it 10 slides for 15 seconds each, for example.

You could also add rules such as “no more than three words on each slide” (or “no words”) so that students must really talk and not just read the slides. They need to be given a good amount of time, either at home or in class, to prepare themselves and practice their timing. It can also be prepared and presented in pairs, with each partner speaking for half of the slides.

*PechaKucha originated in Tokyo (in 2003). The name means “chitchat.”

“Nowadays held in many cities around the world, PechaKucha Nights are informal and fun gatherings where creative people get together and share their ideas, works, thoughts, holiday snaps—just about anything, really.”—the PechaKucha 20×20 format.

15. Two Texts

This challenging task is great for more capable students and it involves reading. Having texts in front of them can make adult students feel more supported.

Choose two short texts and print them out. Print enough of each text for half of the class. Create a list of simple questions for each text and print out the same quantity.

Divide the class into two groups and hand out the texts. Hang onto the question sheets for later. One group gets one text, the second group gets the other text. The texts can be about related topics (or not).

Group members then read their texts and are free to talk about them within their group, making sure they all understand everything. After five minutes or so, take the papers away.

- Each student is paired with someone from the other group. Each student must tell their partner everything they learned from their text. Then they must listen to (and remember) what the other student tells them about their group’s text.

- Students return to their original groups and are given a list of questions about their original text.

- Students are paired again, this time with a different person from the other group. Each student must test their partner using the questions about the text—which their partner never read and was only told about. Likewise, the students quizzing their partners must answer questions about the text they were told about.

On another day, use two different texts and try this activity again. Students do remarkably better the second time!

16. Discuss and Debate

More mature students can discuss and debate issues with a partner. They can even be told which side of the argument they should each try to promote. This could be a precursor to a full-blown classroom debate.

Working with a partner or small group first gives them an opportunity to develop and practice the necessary vocabulary to speak confidently in a larger forum.

It would be a good idea to debate something relevant to the topics you are studying currently, as it will mean that your students have a bigger bank of information and vocabulary to pull from and keep the conversation flowing.

You could have smaller groups debate in front of the rest of the class, and have the other students decide on who they think won the debate by the end of it, explaining their reasons why. This ensures that both their speaking and listening comprehension skills are being tested, and keeps the whole class engaged.

Depending on the level of your students, you can change the level of the debate topics you assign them. This makes it a great accessible option for a range of learners, which you can easily customize based on the needs and interests of your students.

17. Untranslatable?

If you happen to have students in your classroom with different native languages, they’ve almost certainly stumbled across words without direct English translations. You can use your students’ expertise in their own languages to spark conversation in the classroom.

1. Divide the class into small groups of students—preferably, each group of students will represent two or more native languages.

If the students in a group all speak the same native language, no worries—there are still different dialects, regionalisms and variations in individual experiences to drive conversation about each “untranslatable” word and its possible English definition.

2. Ask each student to come up with a small handful of words that they cannot translate directly into English.

3. Students will then take turns presenting to their respective groups, pronouncing each featured word and explaining—to the best of their ability—what it means in English.

4. After the presentation of each word, the other students will have the opportunity to ask questions, to clarify the word’s meaning and usage.

5. Where possible, each student who hears a presentation can also be asked to think of a word in their own language that means the same as the presenter’s “untranslatable” word.

6. Depending on the skill level of your students, they can also participate in an open discussion of the featured word and its meaning after the presentation.

This activity encourages students to conceptualize the meanings of words in both their native language and English.

18. Skill Share

1. Ask each student to come up with a hobby or skill they can share with the rest of the class in a short presentation. You can give them several days to prepare ahead of time.

2. If you have a larger class, you can divide your students up into teams to allow each student more time to present in a smaller group setting. You can also pair off your students, so one student will take turns presenting to one other student only.

3. Students will take turns making a short presentation to their respective audience. In their presentation, they should explain their chosen hobby, skill or activity in clear terms that can be easily understood.

4. Within their presentations, students will also give simple, step-by-step instructions, to teach their audience members the target skill.

5. After each presentation, the student’s audience must ask the presenter at least one relevant question pertaining to the skill or activity in question. The questions should clarify their understanding of the process.

6. When the presentations and “Q & A” sessions are done, students can pair off with other partners or form new teams.

Variation:

Audience members can use the information they’ve gleaned from a teammate’s presentation to explain the process they’ve learned to someone in the class who didn’t hear the original presentation.

The original presenter can act as a subject matter expert, prompting their former audience member (as needed) to explain the process more clearly.

Activities to Build Speaking Confidence

19. Reading Aloud for Fluency

All you have to do is select a piece of text, which students will practice reading out loud until they can read it fluently. The goal is to work towards reading the text in front of an audience.

Short pieces like poems work best here, as students tend to memorize them easier. The websites Poetry Out Loud and Classic Poetry Aloud are great for finding such poems.

Don’t forget to have the students focus on body language as well as how they speak. If they don’t know how to appear confident, start with a small lesson about body language. Give them a checklist so they can use it as a reference. For example:

- Are you standing tall?

- Are you looking at the audience?

- Are you speaking loudly enough?

- Are you enunciating your words?

- How is the tone of your voice?

- Are you smiling?

Once your students understand how to speak and focus on body language, have them read the text in front of a mirror. When they feel they are ready, have them read it in front of you, then work up to reading with a partner.

You can track their progress in class by filming their speeches so students can see the progression. Let them know that no one else will see what you filmed.

An activity like this should last no longer than a month, or else students might get bored of it. At the end of the month, students can present their poems/texts to the class.

20. Mimicking Public Figures

Watching videos of public figures can help students see good examples of how to appear confident. Public figures can include news anchors, politicians or even famous celebrities.

Start off by doing a class activity where the students analyze why the public figure they are watching is so confident. You could use a checklist, and have students look for each element while they’re watching, or leave it open-ended.

While the students are discussing, write their answers on the board. You can watch a few short videos at a time for your student to see if there any commonalities. John F. Kennedy and Steve Jobs are great examples of speakers to observe in your class.

Once you’ve identified the qualities of confident speakers, students can then begin mimicking. Start off with a short video or give the students a choice between several. Students should simply mimic what they see on the video—including body language and tone.

It’s easiest to copy the speaking if there’s a transcript or subtitles available, so a short fragment from a TED Talk, captioned YouTube video or an exciting video from FluentU would be a suitable idea.

Have your students move on to longer videos when they are ready. Depending on your class, you can have them show you what they’ve done and conference with you about how it has helped them before moving on to longer videos.

21. Sharing Struggles with a Trusted Person

Having students share their struggles with you is great for building rapport and trust between teacher and student. The more they trust you, the more feedback you can get about your lessons. Students might also come up to you and ask for help, which in turn help them get extra practice.

Don’t introduce this activity until you’ve known the students for at least a month. You want them to be familiar with the class and you before asking them to reveal their feelings. Any sooner and it may backfire on you.

To begin, tell a story about something you’ve struggled with (it doesn’t have to be academic, as long as it’s a skill you were trying to learn) where sharing your woes helped you push on. Give them time—a week or so—to think about what they’ve been struggling with and to record it somewhere.

After a week, tell your students that you will start conferences with them and in groups. Make sure they don’t feel pressured to share all their struggles in the beginning, even something small will help them.

Don’t fall into the trap of allowing students to complain or compare themselves with other students. If they do this, it will only make them feel worse about themselves. If you see this happening in groups or during your conferences, redirect the conversation to focus on just the student who is sharing.

22. Reflecting on Successful Past English Classes

Sometimes students are so focused on what they have to achieve that they forget how far they’ve come already. Asking your students to reflect on past English classes forces them to see where they used to be and where they are now.

In fact, many of your students will probably be very surprised at how much they have progressed. This serves as a confidence booster, and also as motivation to continue pushing themselves.

Some ideas for how to have your students reflect include writing in a journal, keeping a learning log, collecting works in a portfolio and periodically filming them thinking or reading out loud.

Set aside some time to conference with students regularly about their progress—every two weeks or monthly. Make sure you keep your own conference notes so you can also see how the student has progressed.

Take a look back through the lessons you taught at the beginning of the course as a class to show your students what you were doing as a class then, versus now. Reassure them that they will continue to learn, and that in a few months they will look back on the challenging material they are studying now and find it much easier.

23. Reading Stories of Progress

When your students are feeling discouraged, it’s a great confidence booster to see how other people have also struggled yet improved and grown. Make sure not to label these “success stories” though, as you don’t want to give students the false view that their English (or anything!) is either a failure or a success.

The most important takeaway is that learning is a journey where you’re constantly developing and progressing. Mistakes and weaknesses are not “failures,” but natural and necessary. Reading stories of others’ struggles and progress helps students to see that it will take time—they just need to persevere and put in continual effort.

If possible, invite some of your past students to share their stories with your current class. If this is not possible, look for written articles or stories that you could base a lesson on—such as stories of famous celebrities whose first language isn’t English.

For example, Arnold Schwarzenegger immigrated to the United States and commonly shared how hard he worked on his pronunciation when he was trying to break into Hollywood. Penelope Cruz didn’t begin learning English until age 20, and in several interviews, she mentions common English mistakes she made when first arriving in the USA.

The above ESL activities for adults are sure to help your students come out of their shells and practice their speaking skills—all while having fun!

Check out this article next:

How to Teach English to Adults: 10 Engaging Activities | FluentU English Educator Blog

Wondering how to teach ESL to adults? While your lessons might be a bit less chaotic than with younger students, they don’t have to be dull or boring. Everyone enjoys…

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)