Italian Moods: The Complete Lesson

In Italian, a mood is the form of a verb that shows how it is expressed, not just when the action happened.

In English, for example, there are four moods: indicative, imperative, subjunctive, and infinitive. In Italian, there are seven.

Although this abundance of moods is sometimes considered to be one of the trickier parts of learning Italian grammar, this guide will give you a good feel for when to use each one.

Contents

- What Are Italian Moods?

- How Are Italian Moods Different From Verb Tenses?

- The 7 Italian Moods And How to Tell Them Apart

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

What Are Italian Moods?

Italian moods work together with verb tenses to add a shade of meaning.

They tell you the manner in which the verb is being used or how the verb is meant to be understood, not just its place in time.

For this reason, moods and tenses are often combined.

How Are Italian Moods Different From Verb Tenses?

On the surface, Italian moods seem very similar to verb tenses. In fact, many Italian language professors teach moods as just an extension of tenses.

Some native Italians (like my husband) didn’t even know there was a distinct word for them in English!

Here are the biggest differences between moods and tenses:

When vs. How

Verb tenses tell you when in time an action occurred. “Lui è al cinema,” for example, means he is at the cinema right now. This is the presente (present) tense.

Moods, on the other hand, tell you how the speaker feels about what he or she is saying, or how certain they are about it.

For example, the congiuntivo (subjunctive) mood’s “Credo che lui sia al cinema” means “I believe he is at the cinema,” but implies that the speaker is not totally sure.

Moods let you talk about an action’s position in reality

That sounds kind of trippy, but to put it simply, moods tell you whether something is really happening or not.

“Spero che domani vada meglio” means “I hope tomorrow is better,” but it isn’t a guarantee. It is a hope, dream, possibility, opinion, or wish expressed with the congiuntivo.

But, if I say “Domani andrà meglio” in the indicativo (indicative) mood, I am certain that “Tomorrow will be better.”

Moods have an element of feeling to them

As the word “mood” implies, moods can also reflect the feelings of a speaker.

With the imperativo (imperative) mood, for instance, you are giving an order in an authoritative or sometimes angry way. E.g. “Dammi quella matita” (“Give me that pencil”).

As opposed to the less intense condizionale (conditional) version: “Potresti darmi quella matita, per favore?” (“Could you give me that pencil, please?”).

Moods allow you to speak in the hypothetical

The condizionale can also help you to express something entirely hypothetical.

It is usually an instance of cause and effect, where the speaker means “if this condition were met, this other thing would happen.”

For instance: “Se tu fossi stato qui, mi avresti aiutato” (“If you had been here, you would have helped me”).

The 7 Italian Moods And How to Tell Them Apart

There are seven Italian moods in total, and they are broken down into two groups: finite and indefinite.

Modi finiti (finite moods) are moods in which the verb form tells you who is doing the action. They are conjugated based on the person and the number of people the speaker is talking about. There are four of them, and each one branches off to include one or more verb tenses.

Modi indefiniti (indefinite moods), on the other hand, don’t have a defined subject so they don’t tell you who is doing the action.

Let’s take a deeper look at both types so you can see what I mean.

The Finite Moods

1. indicativo (indicative)

The indicativo is the most commonly used mood.

It is used to describe things that happen in reality, and can be used with almost all present, past, and future tenses.

Here are some example conjugations for three regular present tense verbs, one for each of the main verb groups (-are, -ere, and -ire):

| parlare - to speak | leggere - to read | dormire - to sleep | |

|---|---|---|---|

| io | parlo | leggo | dormo |

| tu | parli | leggi | dormi |

| lui/lei/Lei | parla | legge | dorme |

| noi | parliamo | leggiamo | dormiamo |

| voi | parlate | leggete | dormite |

| loro | parlano | leggono | dormono |

examples:

Parlano italiano a casa. — They speak Italian at home.

Leggo un libro ogni mese. — I read a book every month.

La domenica, dormiamo fino a tardi. — On Sundays, we sleep late.

You can also use the indicativo mood in the following tenses:

- Imperfetto (imperfect)

- Passato prossimo (present perfect)

- Passato remoto (remote past)

- Trapassato prossimo (past perfect)

- Trapassato remoto (preterite perfect)

- Futuro semplice (simple future)

- Futuro anteriore (future perfect)

Since these are the standard tenses and work in the standard way, we won’t go into them here, but if you need to brush up, here’s our full guide to Italian verb tenses.

2. imperativo (imperative)

Imperativo means imperative, in the sense that the speaker is giving a command. This one is only used in the present tense.

It usually corresponds to the tu, lui/lei, noi, and voi forms because the speaker is telling someone else to do something.

Very rarely it is used with loro as well, but that’s a special case no one really uses anymore.

| io | Parla! | Leggi! | Dormi! |

| lui/lei/Lei | Parli! | Legga! | Dorma! |

| noi | Parliamo! | Leggiamo! | Dormiamo! |

| voi | Parlate! | Leggete! | Dormite! |

| loro | Parlino! | Leggano! | Dormano! |

Examples:

Parla! — (You) Speak!

Leggete quel libro! — (You all) Read that book!

Dormiamo adesso! — Let’s go to sleep now!

The pronoun is rarely used here as it is usually understood by the context.

There is also a particular format used when you are telling a person not to do something. The infinitive of the verb is used instead of a conjugation:

Non parlare così! — Don’t talk that way!

3. congiuntivo (subjunctive)

The congiuntivo or subjunctive tense is used to express opinions, hopes, dreams, wishes, probability or possibilities.

This one has four different sets of conjugations based on when the action took place.

Here’s a breakdown of each one:

congiuntivo presente (subjunctive present tense)

The congiuntivo presente is concerned with hopes, beliefs, wishes, etc. that take place in the current moment.

The conjugations for present-tense singular subjects (I, you, he/she/it) all have the same ending, so the pronoun is often used before the verb to make it clear who the speaker is talking about.

| parli | legga | dorma |

| parli | legga | dorma |

| parli | legga | dorma |

| parliamo | leggiamo | dormiamo |

| parliate | leggiate | dormiate |

| parlino | leggano | dormano |

Most of the time, you can tell that the congiuntivo is needed because of the presence of “che” (that) in a sentence.

Examples:

Credo che tu parli bene l’italiano. — I think that you speak Italian well.

È meglio che io legga questo libro in fretta. — It’s best that I read this book quickly.

Pensi che lei non dorma abbastanza? — Do you think that she doesn’t sleep enough?

congiuntivo passato (subjunctive past, a.k.a. subjunctive present perfect tense)

You must also learn the passato prossimo or present perfect tense of verbs in the congiuntivo.

Luckily, you only have to master the auxiliary (helping) verb format of avere and essere in the subjunctive.

Then you just proceed with the past participle like you would in the indicative past tense form you are used to.

This form is often used in a sentence with another verb like sperare (to hope), credere (to believe) or pensare (to think), which are usually in the present tense.

| abbia parlato | abbia letto | abbia dormito |

| abbia parlato | abbia letto | abbia dormito |

| abbia parlato | abbia letto | abbia dormito |

| abbiamo parlato | abbiamo letto | abbiamo dormito |

| abbiate parlato | abbiate letto | abbiate dormito |

| abbiano parlato | abbiano letto | abbiano dormito |

Examples:

Spero che vi abbiano parlato delle nuove regole. — I hope they talked to you about the new rules.

Credi che io abbia letto quel libro? — Do you believe I’ve read that book?

Non penso che abbiano dormito stanotte. — I don’t think they slept last night.

For the verbs that take essere as an auxiliary verb, you use the following conjugations for that first half of the construction:

sia

sia

sia

siamo

siate

siano

Penso che lui sia andato al supermercato. — I think he went to the supermarket.

congiuntivo imperfetto (subjunctive imperfect tense)

Last but not least, we have the subjunctive form of the imperfect tense.

This one is used when talking about an ongoing wish or hope that took place in the past or in a conditional situation.

The trademark of this tense is all the “s”es, which makes it pretty easy to ssspot.

| parlassi | leggessi | dormissi |

| parlassi | leggessi | dormissi |

| parlasse | leggesse | dormisse |

| parlassimo | leggessimo | dormissimo |

| parlaste | leggeste | dormiste |

| parlassero | leggessero | dormissero |

Speravo che tu parlassi di píu. — I was hoping that you would speak more.

Pensavo che lui leggesse tanti libri, ma non gli piacciono. — I thought he would read a lot of books, but he doesn’t like them.

Lana credeva che i bambini dormissero. — Lana believed the kids were sleeping.

congiuntivo trapassato (subjunctive past perfect tense)

The trapassato (past perfect) tense is for possible actions that would have (in theory) been completed before another action that has also been completed.

It is formed by taking the subjunctive imperfect form of the auxiliary verb avere or essere and adding the past participle of the main verb.

With the congiuntivo trapassato form, the other verb in the sentence is usually either in the imperfect or a past tense form.

| avessi parlato | avessi letto | avessi dormito |

| avessi parlato | avessi letto | avessi dormito |

| avesse parlato | avesse letto | avesse dormito |

| avessimo parlato | avessimo letto | avessimo dormito |

| aveste parlato | aveste letto | aveste dormito |

| avessero parlato | avessero letto | avessero dormito |

Examples:

Speravo che ne avessero parlato prima dello spettacolo. — I hoped they had spoken about it before the play.

Pensavo che Anna avesse letto questo libro. — I thought that Anna had read this book.

Temeva che i bambini avessero dormito troppo poco. — She feared the kids hadn’t slept enough.

If the verb takes essere, use the following as the auxiliary verb forms:

fossi

fossi

fosse

fossimo

foste

fossero

Credevo che Andy fosse partito quella mattina. — I thought Andy had left that morning.

4. condizionale (conditional)

The condizionale mood, as its name implies, is conditional. It’s used to speak about things that are hypothetical, and that would only occur if another condition were met.

This one only has a present tense and a past tense form.

condizionale presente (conditional present)

The present tense form of the conditional mood expresses something that could happen right now if something else occurred.

It’s formed by taking the infinitive of the verb, dropping the -e from the end, and adding a new ending. But watch out: –are verbs change to –ere in this mood.

| parlerei | leggerei | dormirei |

| parleresti | leggeresti | dormiresti |

| parlerebbe | leggerebbe | dormirebbe |

| parleremmo | leggeremmo | dormiremmo |

| parlereste | leggereste | dormireste |

| parlerebbero | leggerebbero | dormirebbero |

Examples:

Parlerebbe di più se tu smettessi di parlare. — She would talk more if you stopped talking.

Leggeresti il mio libro se te lo prestassi? — Would you read my book if I lent it to you?

Dormiremmo meglio se spegnessimo la luce. — We would sleep better if we turned off the light.

In most cases, the verbs used in sentences in this mood are both in the conditional tense, since they are both hypothetical.

condizionale passato (conditional past or conditional present perfect)

Condizionale passato is simply a conditional form of passato prossimo.

This one expresses a hypothetical or even impossible situation that would have happened in the past if something else had enabled it to do so.

It is formed by using the conditional form of the auxiliary verb avere or essere plus the past participle of the verb you are using.

| avrei parlato | avrei letto | avrei dormito |

| avresti parlato | avresti letto | avresti dormito |

| avrebbe parlato | avrebbe letto | avrebbe dormito |

| avremmo parlato | avremmo letto | avremmo dormito |

| avreste parlato | avreste letto | avreste dormito |

| avrebbero parlato | avrebbero letto | avrebbero dormito |

Examples:

Avrei parlato con lei se fosse stata qui. — I would have spoken to her if she had been here.

Avrebbe letto l’articolo se fosse stato scritto in inglese. — She would have read the article if it had been written in English.

Se non fosse stato così tardi, avremmo dormito di più. — If it had not been so late, we would have slept longer.

If the verb you’re using takes essere, use these forms as the auxiliary:

sarei

saresti

sarebbe

saremmo

sareste

sarebbero

Sarei andata se me lo avesse chiesto. — I would have gone if he had asked me to.

The Indefinite Moods

5. infinito (infinitive)

The infinitive is the base form of the verb, the one you would see in a dictionary.

It is also used in certain sentence constructions, especially with piacere or modal verbs.

| parlare - to speak | leggere - to read | dormire - to sleep |

Examples:

Sono felice di parlare con te. — I am happy to speak with you.

Non mi piace leggere. — I don’t like to read.

Non posso dormire troppo tardi. — I can’t sleep too late.

6. participio (participle)

There are two participle forms in Italian: the present participle and the past participle.

The participio presente or present participle is used to turn the verb into a noun, adjective, or adverb.

Most present participles are formed by replacing the final -are with ante or -ere/-ire with –ente (some ire verbs take -iente instead).

There are exceptions, though, so it’s best to do a bit of research and memorize the outliers.

| parlante - speaker | leggente - reader | dormente, dormiente - sleeper |

Examples:

Scooby Doo è un cane parlante. — Scooby Doo is a talking dog.

Il Vesuvio è un vulcano dormiente molto pericoloso. — Vesuvius is a very dangerous sleeping volcano.

“Leggente” is a verb that has gone out of fashion, so I won’t make a sentence with that one, but you get the idea!

The past participle, on the other hand, is used to form other verb tenses.

You might best recognize it as a part of the past tense, but it is used in several other tenses (and moods!) as well.

Usually, -are becomes -ato, -ere becomes -uto and -ire becomes –ito.

These verbs are always used with the appropriate auxiliary verb.

| parlato | letto | dormito |

Examples:

Ho parlato con lei ieri. — I spoke to her yesterday.

Hai letto il giornale oggi? — Did you read the newspaper today?

Non ho dormito per tre giorni. — I didn’t sleep for three days.

Leggere is an irregular verb in this form, but other, regular -ere verbs like credere become creduto.

Again, the best way to learn the exceptions is to memorize them, as there isn’t an easily explainable rule here.

7. gerundio (gerund)

In Italian, the gerund is used to form continuous tenses. It is equivalent to English words that end in -ing.

Verbs ending in -are replace the ending with –ando, and -ere and -ire verbs replace their endings with –endo.

An auxiliary verb in the present or infinitive form is usually needed to form a complete thought.

| parlando | leggendo | dormendo |

Examples:

Sto parlando con mia madre. — I am talking to my mother.

Stavo leggendo un libro quando sei arrivato. — I was reading a book when you arrived.

Il gatto sta dormendo sul letto. — The cat is sleeping on the bed.

Note that the auxiliary verb most often used with gerunds is stare, not essere.

It also means “to be,” but has a slightly different meaning based more on the condition than a state of being.

Okay, that was a lot to learn, but I hope I didn’t put you in a bad mood! Once you master these seven Italian moods, you will know the proper way to express yourself no matter how you’re feeling.

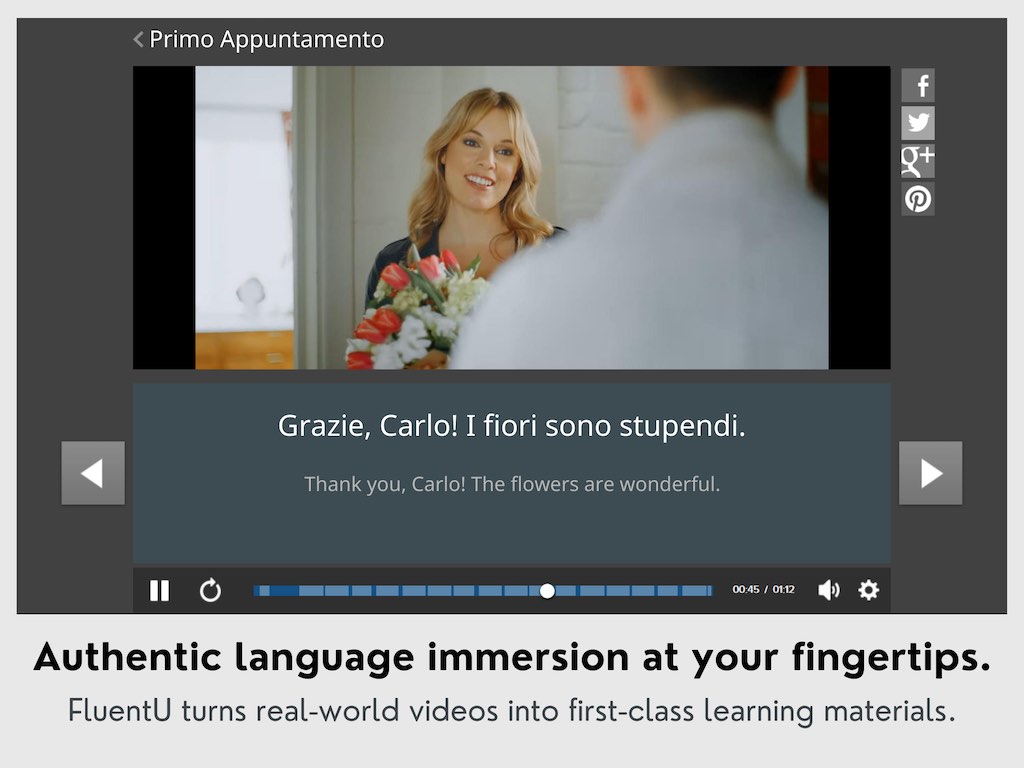

A good way to see how these moods are used in context is by using a language learning program such as FluentU.

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)