The Direct Method of Language Teaching: 5 Useful Techniques

Ever heard of this language teaching approach that professes never to teach any grammar?

You won’t hear a word of English—or whatever the students’ native language is—spoken in the classrooms that operate with this method.

I’m talking about the direct method of language teaching.

Here, we’ll take a deeper look into its philosophies and see if it’s something you’d want to try out in your classroom.

Let’s begin.

Contents

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

What’s the Direct Method?

Around the turn of the 19th century, a method arose that served to right the shortcomings of the grammar-translation method—the most prevalent language teaching approach in those days.

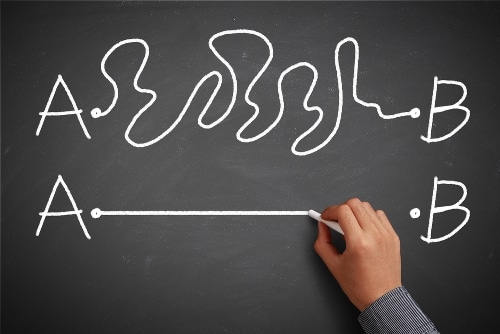

The direct method was developed as an antithesis to grammar-translation method. When the grammar-translation method’s weaknesses became apparent, the direct method expressly addressed those competencies scarcely touched by its predecessor.

So what’s the grammar-translation method? Let’s review.

It’s the teaching method that puts grammar—its rules, morphology, syntax—at the forefront. Meaning, language is taught by analyzing the different elements of language and explicitly prescribing correct ways of combining those elements.

A teacher composing a sample sentence on the board, and then labeling the words as nouns, verbs and adjectives while explaining how they relate to each other, is using grammar-translation method to teach language. The approach is usually championed in textbooks where the different parts of speech have their own chapters and, at the end of each chapter, practice exercises abound.

The “translation” part of “grammar-translation” is embodied in the vocabulary lists that give the equivalents of words in the target language. Translation exercises where students are asked to translate words, phrases and sentences are often used.

The grammar-translation method is especially adept at developing writing and reading skills, which is very important in dealing with Latin and Greek—dead languages, but for which a wealth of preserved literature abounds. But when it comes to practical, modern, spoken languages, it hasn’t resulted in students with communicative ability to carry an interesting conversation in the target language.

So now comes the direct method, a repudiation of its predecessor.

As we shall soon see, grammar, which is at the core of the grammar-translation method, isn’t even expressly taught in this approach. There are no grammar exercises, no committing of rules to memory, no lessons on how to write the plural form of a noun or how to conjugate a verb. That’s why it’s also known as the “anti-grammatical method.”

And while the grammar-translation is taught using the students’ first language, the direct method uses only the target language. Imagine! In a Spanish class that uses this method, you’d only use Spanish to teach your students the language.

The direct method is also known as “the natural method” because it looks to the process of first language acquisition to set the context and techniques for second language acquisition. When we learned our mother tongue, we didn’t go through grammar lessons and translation drills. So, how did we learn our first language?

Well, why don’t we look more closely into these things in the next section.

The Principles of the Direct Method

Language is learned inductively

As mentioned before, grammar isn’t explicitly taught in the direct method.

You won’t be telling students about rules and such. Instead, you’ll let your students figure out the rules for themselves. Your job is to give them plenty of materials to piece together so they can connect the dots and discover the parameters for themselves.

Just as we acquired our first language through repeated exposure, so should it be in class. We didn’t memorize anything for our mother tongue, we simply acquired it through repeated exposure.

So, how do you teach grammar when you aren’t supposed to point out any linguistic rule?

It’s actually easier than you think. And, as a fulfilling bonus, you get to witness your students slowly figure things out for themselves.

Students learn best when you teach them things that are only slightly beyond their reach. And you help them “get there” by giving them simple inputs that they can actually use to figure things out.

Let’s say that in a German class you want to teach the word for the color red—a vocabulary lesson. Instead of using direct translation and writing on the board, “RED = ROT,” you make things more interesting and more fun. Bring several objects of the color—perhaps a red truck, a red ball, a red cap, a rose and lipstick.

Every time you point to the objects, say “Das ist rot. Rot.” (This is red. Red.) Go through the different objects and keep on repeating “rot.” With repeated exposure, your students will soon get the point. To check for comprehension, point to an object of different color, say a blue pen, and ask, “Rot?” The class should give a resounding “Nein!” (No!)

Let’s say that in an ESL class you want to teach some grammar rule, like how to form the plural of nouns. You might want to bring two sets of pictures. One depicting lone objects, the other, depicting a group. You hold the pictures side by side, clearly enunciating, for example, “car” on your right and “cars” on your left. Repeat this process for several pairs of pictures, emphasizing the “s” sound each time.

Your students will pick up on the clues and figure out the rules for themselves. Now you have to trust them on this. They may not get it right away, they may not get all of it, but you have to let those light bulbs work by themselves because this is the kind of learning that really stays with the students.

We’ll have more to say about specific techniques and strategies of the direct method in the next section.

Only the target language is used

This is a biggie: “Only use the target language.” That’s the first thing you read in any direct method lesson plan.

While some do prefer to have some room to throw a little mother tongue here and there, like in teaching vocabulary, direct method purists would never utter a single sound outside the target language.

Even in the first few sessions of the course when members of the class will be absolute beginners and all the words that are coming out of your mouth will sound like Greek to them (even if you’re not teaching Greek), you need to stick the target language when doing your presentations. That is, do everything possible—demonstrating, dramatizing, gesturing—to send your message using only the target language.

The idea is that going through translations only bogs down learning. Students should be trained to think in the target language. Going through translations conditions them to think first in their first language, before converting the information to the target language.

Your students should be trained to see the world through the lens of the target language. In a Spanish class for example, when a student sees a red fruit hanging from a tree, she should immediately be thinking, “la manzana,” not “that’s an apple, hmmm… let’s see, apple is manzana in Spanish. That’s la manzana!”

There should be a direct connection between the sight of the fruit and la manzana. And it’s your job as the teacher to make this direct connection.

The direct method looks to the processes of first language acquisition and applies them a second time to second language acquisition.

When we first learned English, we didn’t have translations to get us through the day. Mommy and daddy talked to us in simple English and we slowly acquired it. Sure, there were times when we made mistakes. But through trial and error, we groped our way to fluency. We not only speak English, we also think and dream in English.

If that’s how your students acquired their first language, then there’s no reason why the same mechanism wouldn’t work in second (or third, or fourth) language acquisition.

This will allow students to excel in authentic situations where the language is actually being used. Because they’re used to this target language-only setting, they won’t be overwhelmed when confronting an unknown word or grammar structure when chatting with a native speaker or watching a video.

Speaking is supreme

In the direct method, listening and speaking skills are given first priority.

This would seem obvious in the field of language learning, but this is in stark contrast to the grammar-translation method where, because of the focus on linguistic structures, reading and writing skills are primarily developed.

Not to sneer at writing and reading skills, but the time to focus hard on them should come later in the language acquisition process.

With the grammar-translation method, you have students who know about the language and can translate a sentence accurately, knowing the different grammatical rules. Unfortunately, they wouldn’t have enough communicative skills to find their way through a speed date. With the direct method, instead of learning about the language, students use the language to send and receive communication.

In the teaching techniques that we will talk about shortly, you will notice that students are actively engaged in the different classroom activities. They’re not just passively sitting while taking down copious notes.

In the direct method, students do a lot of talking, gesturing, acting and interacting. They’re encouraged to talk, no matter how imperfectly. The more talking time the students get, the better. They interact with you, the teacher, they interact with fellow students. Instead of looking at examples of sentences written on the blackboard, they get to feel it roll off their tongues and hear themselves speak in a language they’ll soon be fluent in.

By placing the correct emphasis on comprehension and conversational skills, students are given vivid firsthand experience with the language. They aren’t just learning about the language, they’re actually using it to send a message, perform a task or ask a question.

With the direct method, language is really not an academic endeavor, as it has been for the grammar-translation method. Language is a way to communicate.

5 Direct Method Teaching Techniques

1. Example proliferation

When you only have the target language to use during your lectures, you have to make it up somehow. Example proliferation is one of the ways you do that.

In order for your students to connect the dots and figure out vocabulary and rules of grammar for themselves, you have to give them plenty of material to work with. This means that instead of just giving one or two examples to illustrate your point, you work with five, six or even ten examples. And not only that—you’ll present each of the examples several times. Repetition is key in the direct method if students are to draw the correct conclusions.

The examples that you give should be simple, unambiguous and interesting.

Let’s say you want to teach the class the shapes, say circle. You have many different ways to dramatize this concept. Besides the obvious, which is drawing a circle on the board, you can bring different objects that exhibit the shape. How about a hula hoop, rings, coins, CDs, buttons, cookie, plate, frisbee or medal? How about bringing in pictures of the sun, a rotunda, the London Eye and a pizza?

Notice how difficult it is to resist seeing the connection between what you’re bringing and the concept of “circle?” The more interesting the things you offer to the class, the stronger and more memorable those mental connections will be. When students have pizzas and pies staring back at them, it’s very hard not to get the point.

You can do a comprehension check by presenting an object of a different shape and asking the class if it’s a circle or not.

2. Visual support

A mantra of the direct method is “demonstrate, don’t translate.” When you do example proliferation to drive home a point, you would probably be hitting different learning modalities, different senses. And the most important sensory mechanism to hit—and hit again and again—is the visual sense.

There are many ways you can do this. A simple gesture can make your point vivid and clarify your intent. For example, you can use a close fist to signify strength. Execute it over and over and your ESL students will know what you mean when you say, “This table is built strong.”

The thing is, there’s a whole language based on signs and gestures alone. This can only mean that with enough well-timed actions, a whole new language can be taught.

You can also do actual body demonstrations instead of just using your arms. You can jump, punch, dance, even swim. You can exaggerate body language to provide context cues for your message. Teaching about airplanes? Dramatize it by zooming around class, hopping from one airport to another.

As suggested earlier, you can bring labeled pictures or even the actual objects to help dramatize the content of your lessons.

Of course, the direct method requires that the teacher be prepared. Nothing beats a teacher who knows their stuff.

3. Listening activities

Remember when you were a kid and your mom and dad used to read you bedtime stories?

You probably didn’t understand every word of it. You also probably did not know that it was actually also a great linguistic lesson—especially if one of your parents knew how to modulate their voice and often went overboard telling the story.

Do the very same thing with your students. Read them a story. Preferably the kind with cool pictures. (If you can somehow use a projector to have the images on the wall, so much the better.) Choose a story containing simple sentences.

Pace yourself. The goal of storytelling here isn’t to get to the last page. The story is your vehicle to expose your students to more of the language. So if you need to repeatedly read the sentences several times before proceeding to the next page, then do so.

You don’t need to read verbatim, you can do short asides. For example, if there’s a line that reads, “The lips of the princess were painted red,” you can elaborate a bit by saying, “Red. Just like the rose I showed you earlier, remember?”

So pace yourself. If there’s a particular vocabulary or concept in the story that you want to elaborate, then spend a little more time on it.

Another listening activity that you can do is playing a conversation of two native speakers. They can be talking about anything, as long as they use simple sentences and aren’t conversing too fast. Replay several times, then ask the students about the contents of the dialogue.

The goal in these activities is really not to understand everything. It’s to understand what’s going on. What’s the story about? What are these two people talking about?

If they understand the message, then they’ve just experienced the target language as it’s used to convey a specific message.

4. Oral exercises and tasks

The direct method is a speech-centered teaching approach and believes that there’s nothing like having your students talk in the target language. Make it a clear goal to make your students talk in class as early in the course as possible—in the first class, really.

Grab any excuse you have to make them open their mouths and use the target language. For example, engage them interactively often by asking questions, encouraging them to reply only in the target language. You can ask the class as a whole or random students individually.

“Jerry, how was your weekend?”

“Class, did you see the news this morning? Any reactions?”

“Can anyone tell me their greatest fear?”

Sure, they’ll maybe answer you in the most basic form of the target language that they can muster, even almost incoherently mumbling. But you know that’s all part of the process.

Let them interact with each other. For example, split them up into pairs and let them do question-and-answer dialogues. One of the students will ask all the questions, the other will do the answering. They can ask any question that they want, and the answer given must be as honest as possible.

The goal here isn’t to ask grammatically perfect questions and give grammatically perfect answers. It’s to experience what it’s like to send and receive messages in the target language. After five questions and five answers, make them switch positions and do another five rounds of Q&A.

Also give them opportunities to talk in front of the class. You can extend the previous activity by making them present it in class. Give the pairs a chance to practice a little and put them on deck.

Like I said, every time you find an opportunity to make your students enunciate the sounds of the target language, grab it. Even a simple reading task where you call on each student to read aloud different parts of text in front of the class would go a long way in giving them firsthand experience with the language.

5. Stress free and supportive environment

Providing your students with a stress-free and supportive environment is a standard for all the other teaching approaches, but nowhere is it more important than in the direct method.

Imagine being a student, sitting in your first language class, and immediately the teacher is addressing you in the language that you’re supposed to be learning—even though you haven’t learned a word yet. Everything that comes out of her mouth sounds all Greek to you (even though it’s Spanish or Korean). Yeah, her gestures and tones help somehow, but you can’t be really sure what she means.

Even so, you start picking up a few sounds and tones, a few words here and there that you think have a certain meaning.

The classroom situation is very fluid and you just don’t know when the teacher will call on you and make you stand in front of the class. You can’t just sit at the back of the classroom and fly under the radar until the course finishes.

Imagine that. As good as this is for getting students to be observant, think critically and absorb the language naturally, it could be a little intimidating.

As a teacher, it’s your first responsibility to make every member of the class understand that mistakes aren’t fatal. They don’t have social repercussions. Mistakes are part of language learning and you have to give students enough confidence to participate in class, regardless of uncertainty.

Let them know that you’re there for support. One of the ways you can do this is by making sure that when you call on someone and throw them a question, you never leave without giving the correct answer. For example, you can ask, “Tim, what color is this?” Tim sees that you’re pointing to a yellow banana, but doesn’t know how to respond. What do you do? You feed him the answer and then let him tell it to you.

You: “It’s yellow. Yellow! This banana is yellow. What color is this?”

Tim: “Yellow.”

You: “Very good! Class, the banana is yellow.”

What if Tim ventures on another answer, like “red,” how do you respond?

You give Tim plenty of opportunity to self-correct and guide him to the answer. You can repeat his answer with a questioning tone (“Red?”) then give him options by saying, “Is it red (pointing to something red), or is it yellow (point to the banana)?”

If he mispronounces “yellow,” feed the correct pronunciation to him and let him throw it back to you. In short, nobody in your class gets asked a question without being able to give the correct answer.

Make students feel that you won’t leave them hanging, you won’t embarrass them in class and they’ll be active and willing participants in the learning process.

And that’s what the direct method is all about—a unique method with wonderful virtues of its own.

We’ve talked about its principles and we’ve presented its techniques.

Why don’t you try them in your class today?

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)