Language vs Dialect: What’s the Difference?

“A language is a dialect with an army and a navy.” — Linguist Max Weinreich

Of course you know what a language is, but you may be a little confused about how a language differs from a dialect.

Well, the basic idea is that a language refers to a system of communication with its own unique grammar and vocabulary, often recognized as having distinct cultural or national identity; whereas a dialect is a variant of a language spoken in a specific region or by a particular social group, differing primarily in pronunciation, vocabulary and grammar, but it’s still mutually intelligible (understandable) with the dominant language spoken in the area.

Okay, with that said, read on for three major differences between a language and a dialect, and also learn how a dialect differs from an accent.

Contents

- The Main Differences Between Languages and Dialects

- What’s the Difference Between a Dialect and an Accent?

- And One More Thing...

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

The Main Differences Between Languages and Dialects

I’m going to give it to you straight: even though we’ve defined the differences above, there’s no agreed-upon definition between language and dialect. They’re both systems of communication employed by native speakers and each can be considered complete languages.

It’s tempting to leap to clear-cut comparisons, but in linguistics, some concepts aren’t as straightforward as we want them to be.

1. Languages Have a Country, While Dialects Are Regional

“Language” is defined by Merriam-Webster as “the words, their pronunciation and the methods of combining them used and understood by a community.”

“Dialect” on the other hand is defined as “a regional variety of language distinguished by features of vocabulary, grammar and pronunciation.”

You might have noticed that there’s not much between these definitions. But it’s always pointed out that languages are national, while dialects are said to be regional and are often spoken by a fewer number of people.

Each country has at least one official language that’s used in official documents and government activities.

While most people stop there, we can go a bit deeper—that is, we can be more linguistically accurate.

A dialect becomes a language by decree or declaration—the state gives special status to a spoken system as an official language. In other words, a language is considered a language because it’s been endorsed by the state.

For example, when the Philippines was choosing one of its eight major dialects to be the official language, it was no accident that Tagalog won out.

Even though the majority of the country at the time could scarcely speak Tagalog/Filipino, this didn’t stop the country leaders at the capital, who spoke fluent Tagalog, from adopting it as the national language.

Because languages are technically dialects, there are many situations where people who speak different languages can understand each other perfectly.

Take the mutual intelligibility of the official languages of Denmark, Sweden and Norway for example. Here’s a standard story setup:

Joke: A Dane, Swede and Norwegian walk into a bar…

Punchline: And they talk normally

It’s true. Most Scandinavian people can talk to each other without the use of interpreters!

Officially, they’re speaking three different languages (Danish, Swedish and Norwegian), but it can be argued that they’re really using three related dialects that probably descended from a common mother tongue.

2. Languages Have Standard Written Forms, While Dialects Are Mostly Oral

Languages often have standard grammar rules and abundant supplies of literature. They exist not only as spoken traditions but also as written records.

Dialects, on the other hand, are usually spoken more than written. If they are written, it’s usually not in official or national documents.

While a supply of already-available literature is certainly a criterion for choosing an “official language,” it also works the other way around.

Declaring a dialect to be an official language is self-perpetuating, encouraging writers to create works in that language. Because the state endorsed a certain language as the official language, all of its official affairs will be written in it.

That creates a snowball effect, so more and more literature builds up in that language, strengthening it even more.

3. Languages Are Qualitatively Different from Dialects

Many claim that languages are just inherently more elegant or sophisticated than dialects.

But if you judge this sophistication by the evolved difficulty or complexity of the language, then Archi—a dialect spoken in a mountain region of Russia—would make your French homework look like child’s play.

Archi has a great number of phonemes (sounds) and so many conjugation forms, a single verb can produce around 1,502,839 forms.

If, on the other hand, you’d like to argue that the elegance of a language lies in its simplicity, then you’d be hard-pressed to defend the adoption of difficult languages like Mandarin Chinese, Hungarian or Thai for everyday use.

For example, Chinese has over 50,000 characters. It’s also a tonal language. This means a single syllable like “ma,” depending on how you pronounce it, can either mean “mother,” “horse” or something else completely.

So, who’s really to say what makes a beautiful language? And let’s not forget that there are dialects just as worthy as officially recognized languages.

What’s the Difference Between a Dialect and an Accent?

While we’re on the subject, you might like to know the difference between a dialect and an accent. Many confuse the two and often use them interchangeably. The good news is, the difference is a lot clearer here:

An accent is a subset of a dialect.

While dialects cover all aspects of language—grammar, vocabulary and pronunciation—an accent is concerned with just the third part.

According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, an accent is “a way of speaking typical of a particular group of people and especially of the natives or residents of a region.”

Accents are interesting studies because they organize speakers into their respective geographies. Words and sentences that look the same might come out very differently when spoken by people from two different regions.

With English alone, you already have so many accents. An American can barely understand a Scot, for example, even though they’re speaking the same language.

Each of these, in turn, have their own regional variants. The American accents, for example, are Deep Southern, Texan, New York, Boston, California and many more.

The interesting thing is that most speakers claim their accent is the “correct” way of pronouncing words. That’s how we humans are.

While one’s accent may have some social, economic or geopolitical ramifications, all accents are equal. And everyone has an accent. And they all sound beautiful.

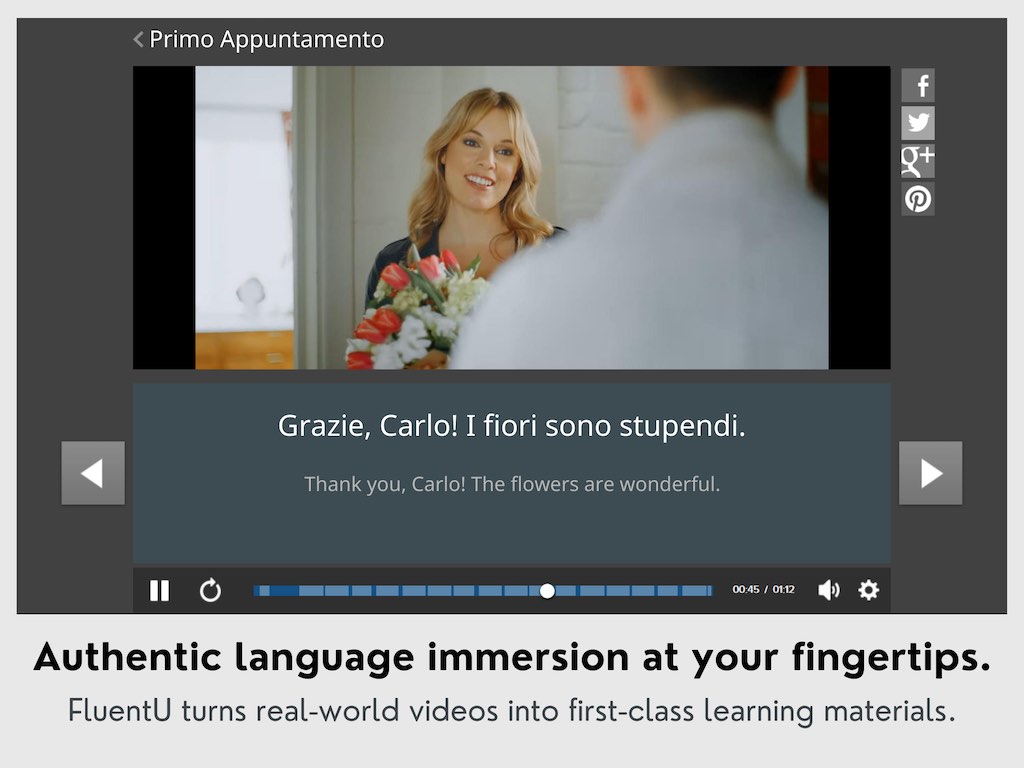

You can get a lot of context and hear various accents by watching media produced by native speakers. One great way to do this is by using a language program like FluentU.

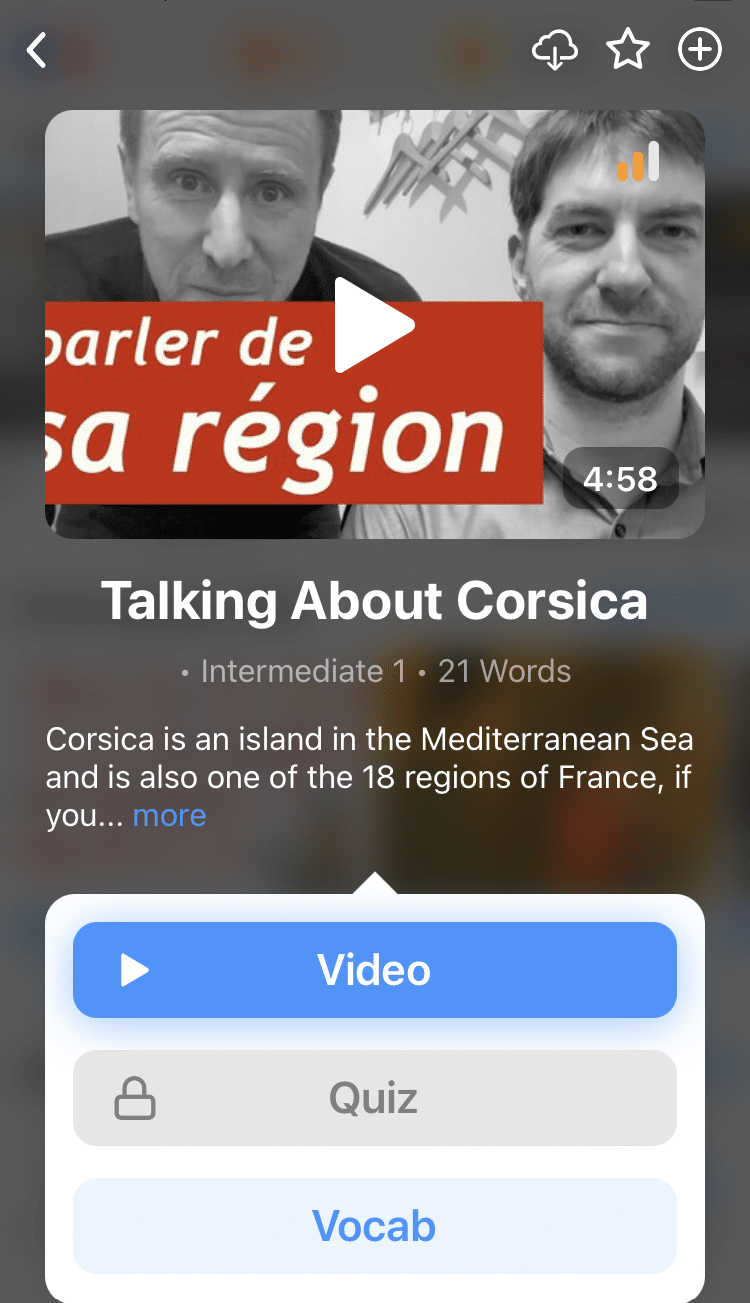

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

If you’re interested in diving deeper into languages versus dialects, consider listening to this informative TED talk:

So now we know: there’s no black-and-white difference between languages and dialects, and an accent is actually a subset of a dialect.

Now you’re equipped to explain the difference to people still in the dark—and maybe even join the discussions of experienced linguists!

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing...

If you dig the idea of learning on your own time from the comfort of your smart device with real-life authentic language content, you'll love using FluentU.

With FluentU, you'll learn real languages—as they're spoken by native speakers. FluentU has a wide variety of videos as you can see here:

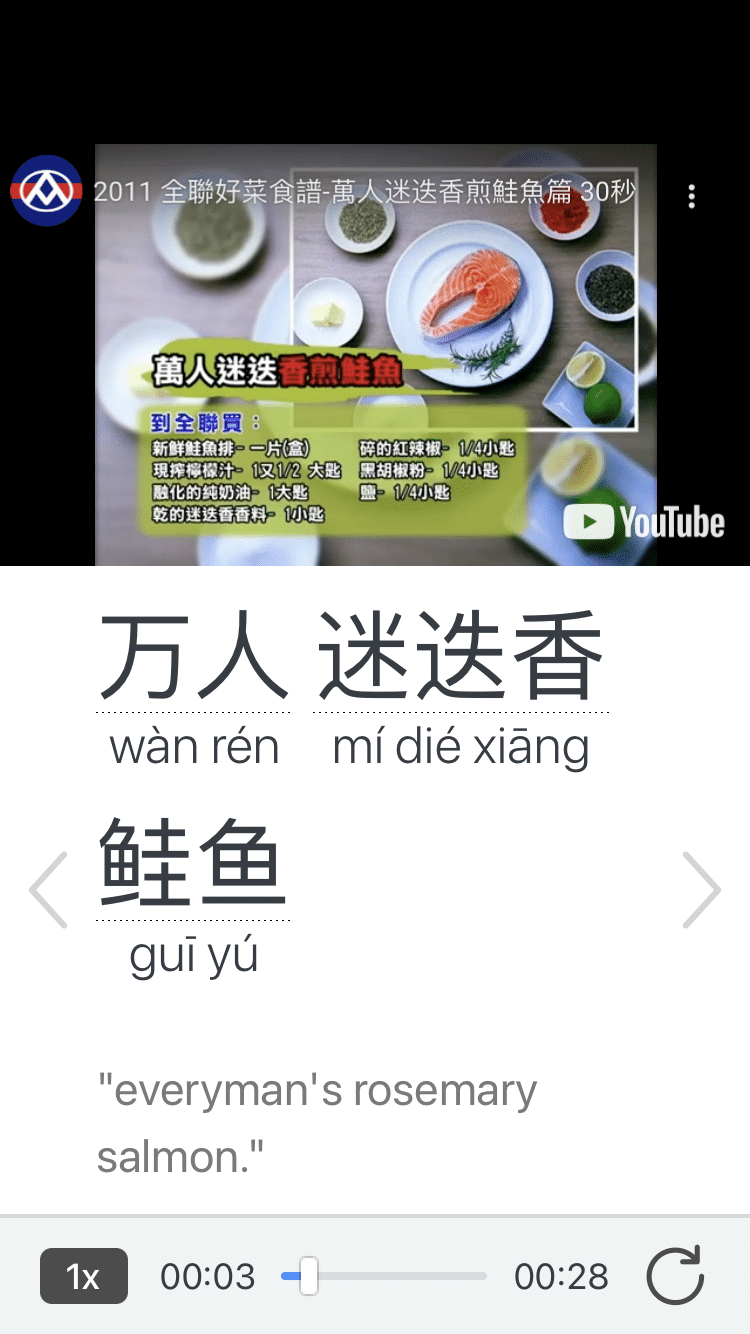

FluentU has interactive captions that let you tap on any word to see an image, definition, audio and useful examples. Now native language content is within reach with interactive transcripts.

Didn't catch something? Go back and listen again. Missed a word? Hover your mouse over the subtitles to instantly view definitions.

You can learn all the vocabulary in any video with FluentU's "learn mode." Swipe left or right to see more examples for the word you’re learning.

And FluentU always keeps track of vocabulary that you’re learning. It gives you extra practice with difficult words—and reminds you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. You get a truly personalized experience.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)