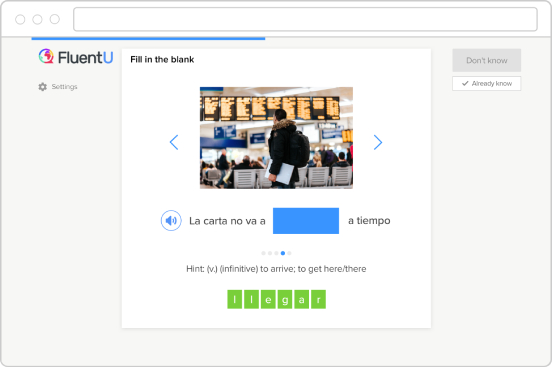

How to learn Spanish with popular TV show clips, movie scenes and songs on FluentU

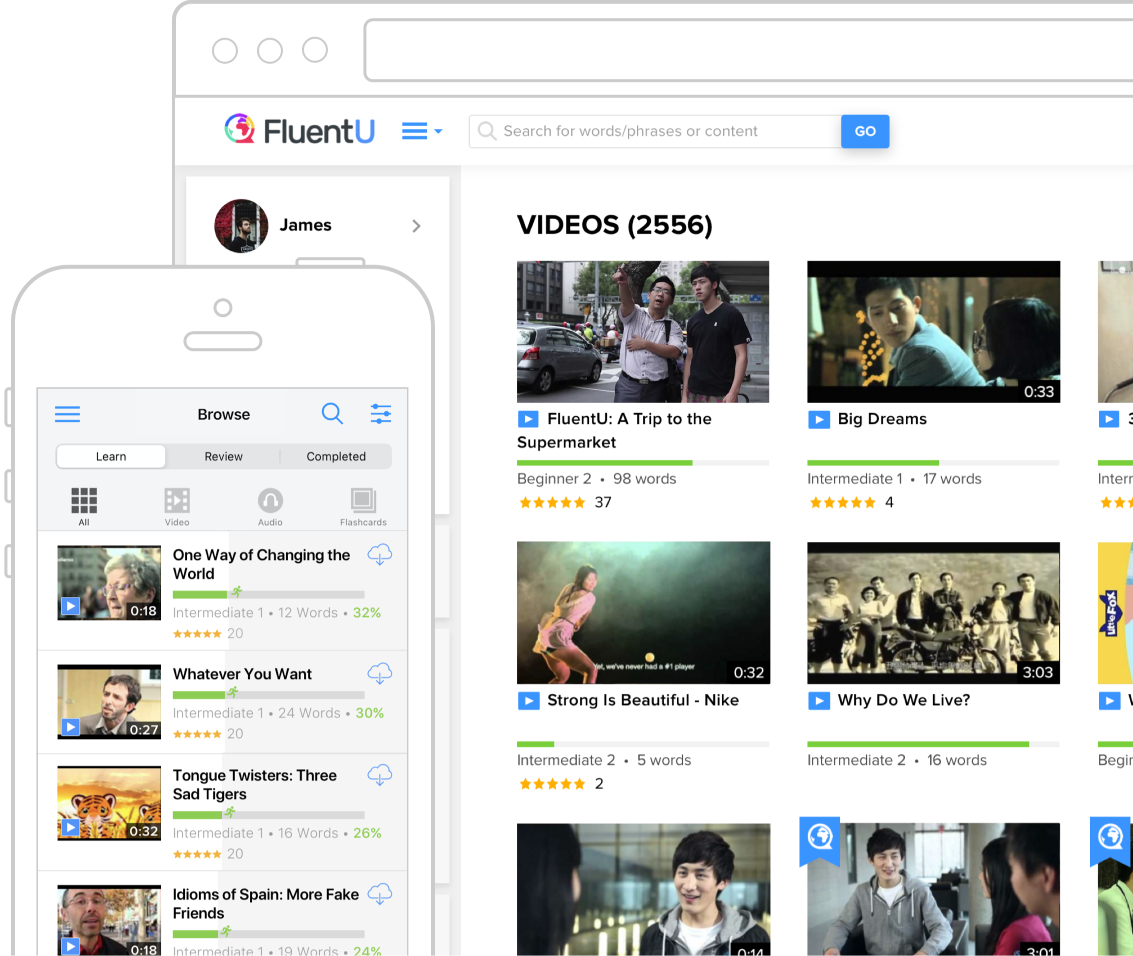

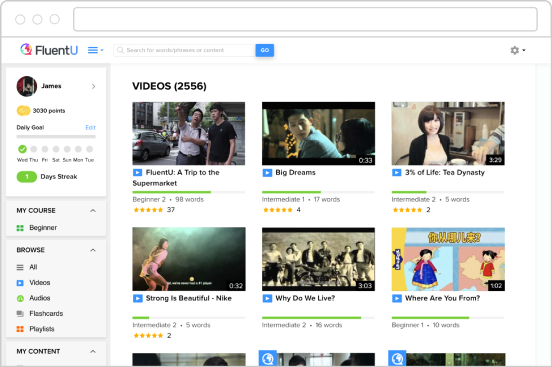

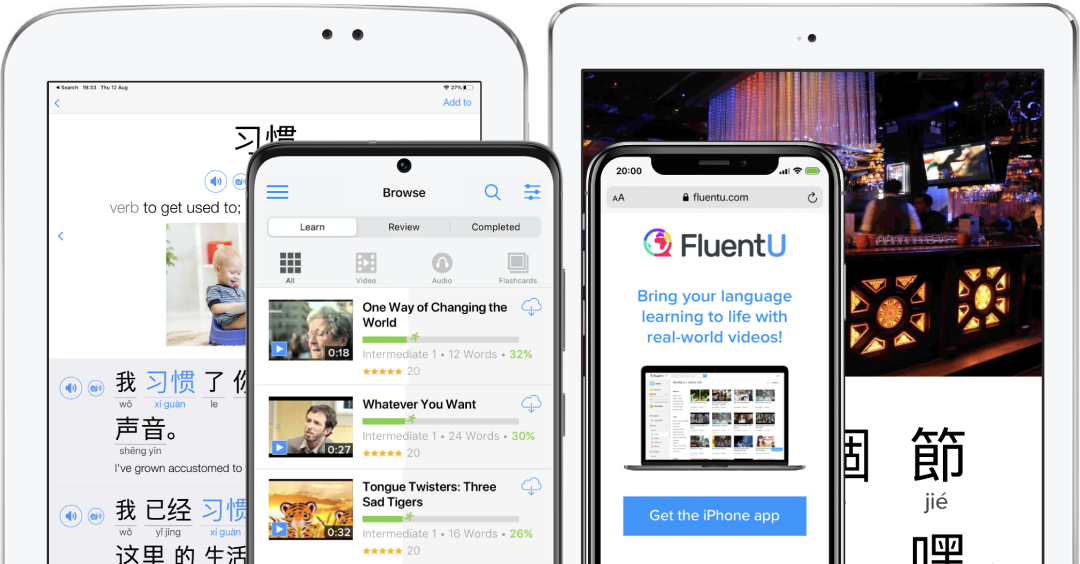

Browse through a curated library of Spanish videos for all levels

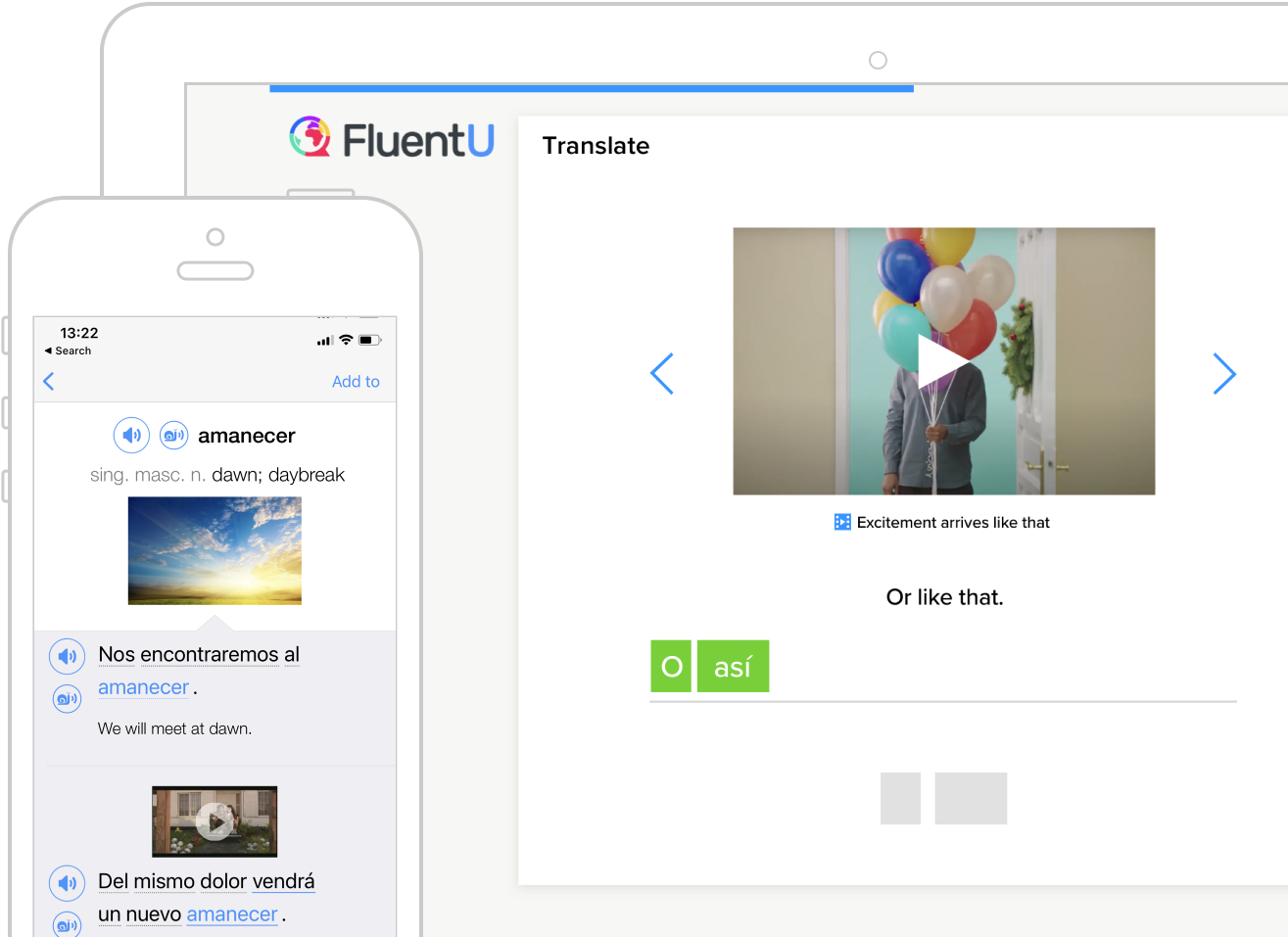

Find authentic Spanish videos that match your learning level with our diverse collection.

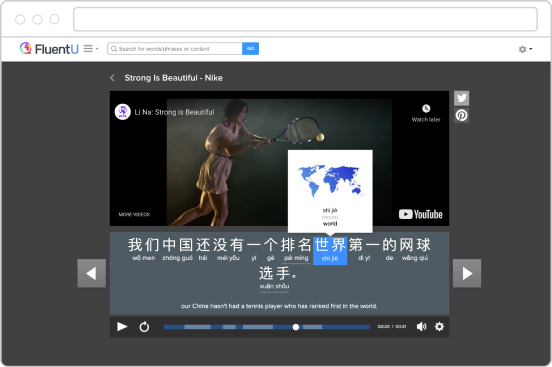

Get to know Spanish the way native speakers use it with videos from both Spain and Latin America. These are sourced from authentic media like telenovelas and hit songs.