How Do We Learn Languages? What Science Says About Adult Language Acquisition

How do people learn languages?

The answer to that question is complicated, but I can tell you one thing from the get-go: You don’t need to be wildly intelligent, especially talented or “good at languages” to learn a language.

Now, learning a language during your formative years is an entirely different beast from learning a foreign tongue as an adult. But, in order to even begin to answer the question “how do we learn languages?,” we have to understand how languages work in general at various stages of our lives.

Once we get that out of the way, we’re going to get into some general tips on how to learn languages.

Settle in, dear reader, because you’re about to be taken for a ride.

Contents

- How Language Acquisition Works in General

- 12 Key Language Learning Tips That Unlock Your Brain’s Potential

- 1. Create a regular habit for language learning

- 2. Be on the lookout for patterns in your target language

- 3. Listen to native speakers of your target language in authentic contexts

- 4. Read authentic texts in your target language

- 5. Use mnemonics

- 6. Use games to learn languages

- 7. Interact with speakers of your target language as much as possible

- 8. Grab a language learning partner to help you out

- 9. Think in your target language as much as possible

- 10. Don’t be afraid to make mistakes

- 11. Remember to study the culture surrounding your target language, too

- 12. Watch authentic videos in your target language

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

How Language Acquisition Works in General

There are plenty of theories on how language acquisition works. One of the most popular and controversial is Noam Chomsky’s universal grammar theory, which posits that all humans possess a natural ability to acquire languages, owing to the idea that all languages share some common features.

Of course, this theory has its fair share of criticisms. For example, the Pirahã language from the state of Amazonas in Brazil is often cited as an example of one that lacks the complex grammatical structures present in many other languages.

If you ask experts from different fields—linguistics, psychology or even genetics—the question “how do we learn languages,” chances are they’ll give you wildly different answers. Still, they’ll probably agree that human language is essentially a system of symbols used to communicate.

For example, we use words like apple, pomme, りんご or تفاحة to succinctly describe the delicious red fruit that doesn’t have an intrinsic relationship to the word we’re saying (or gesturing, if we’re using sign language). It’s just an apple or a pomme or whatever else because we say (or signal) that it is.

So how do we develop this ability to use words and complex grammar structures to quickly tell someone that, hey, this whole language learning thing is pretty cool?

Let’s try to answer that question by looking at and comparing how human children and adults learn languages.

How Children Learn Languages (And Why They’re Better at It Than Grown-ups)

- Human babies are great at recognizing patterns, just like their adult counterparts. A more technical term for this would be “statistical learning”—that is, observing overwhelming amounts of linguistic information and making exceptionally accurate generalizations about patterns deduced from that information. For example, every time you say “bottle” with a bottle in hand to an infant, the baby’s brain starts to connect that word, the sounds you used to produce that word and their possible relationship to that object in your hand.

- Children learn languages through social interactions. As you can imagine, research suggests that children who grow up never being exposed to language (either by accident or due to mistreatment/abuse) end up never being able to harness the full expressive power of languages. By the same token, babies exposed to the spoken form of a language are quickly able to distinguish between subsequent sounds they hear from that language, whether that language is their native tongue or not and only if the languages are spoken by humans and not machines. The researchers went so far as to say that infants have a natural ability to pick up any language (possibly supporting at least some of the tenets in Chomsky’s Universal Grammar theory); however, they gradually lose the ability to do so as they grow up. This might partly explain why it’s harder to pick up languages as an adult.

- Children have greater brain plasticity compared to adults. If a five-year-old child seems to be picking up Spanish faster than you are, don’t despair. They’re likely in the critical period of learning, where they’re neurologically prepared to acquire new skills like communicating in a language that’s different from their native tongue. That’s not to say that adults can’t rewire their brains at all—quite the opposite is true, actually, but we’ll get to that later.

How Adults Learn Languages (Plus, What Gets in the Way of Adult Language Learning and the Good News)

- Like their younger counterparts, adults learn languages by recognizing patterns and through social interactions. Of course, the mechanisms for how these two work in adults is different. But think about it: If you’re reading a book or blog post written in your native language about how to learn your target language, you’ll probably read something like “similar to English, the French prefix mal- means ‘bad'” or “Romance languages have grammatical genders.” This allows you to easily build new knowledge on the foundation of what you already know. And while you can probably practice written conversations with an artificial intelligence (AI) partner, nothing beats immersion in your target language—i.e., exposing yourself to situations where you’ll encounter that language in an authentic context.

- Your first or native language affects the way you learn subsequent languages. This ties back to our earlier point about our use of patterns to learn languages. If you learned English growing up, you’re more likely to pick up a language like Dutch (which uses similar grammatical structures and Germanic root words) than Japanese (which uses entirely different writing and phonetic systems—and that’s not even getting into the grammar).

- Adults communicate in mostly equal relationships, which affects the complexity of the language they use. A baby’s main conversation partners are their parents and other adults, who naturally adapt their speech to accommodate the child’s less advanced linguistic abilities. On the flip side, the vast majority of foreign language speech exchanges force you to engage with the same level and speed as native speakers.

- Adults are less willing to make mistakes (or show that they do) than children, which can hinder language learning. When children make mistakes, we’re more likely to let them off the hook, because they’re still growing up and mistakes are part of the process. Adults, on the other hand, are expected to know better and are more experienced with the consequences of making mistakes, so when we commit missteps, we tend to feel embarrassed and ashamed about them. That’s all well and good for maintaining the social order, but it also discourages us from making the necessary mistakes to advance our language learning, as counterintuitive as that may sound. By knowing what not to do, we can usually make good guesses as to what we should do instead.

- Also, adults have their plates filled to the brim with responsibilities. Unlike children, who only have to worry about balancing school and play, adults have to worry about relationships, jobs, errands, taxes, the economy and the thousand other things we need to do every day just to keep ourselves afloat. In the midst of all that chaos, finding the time to learn a language can be challenging, to say the least.

- Luckily, adult brains are more malleable than you might think. While you probably won’t be able to pick up a language as fast as when you were much younger, it’s still possible to rewire your brain to maximize its language absorptive capabilities. After all, if adult brains can be continuously and negatively impacted by factors like stress and the environment, it’s highly likely that positive factors can affect your brain in the opposite direction, too. In fact, research has shown that human brains continue to change throughout their lifetimes, barring the effects of extraordinary events like severe head trauma.

So if adult brains still have a relatively high degree of neuroplasticity, how do you take advantage of that for language learning? If you’ve made it this far into the post, congratulations: You’re about to be rewarded with concrete answers to that question.

12 Key Language Learning Tips That Unlock Your Brain’s Potential

1. Create a regular habit for language learning

I’d tell you to “set a schedule, and stick to it as much as you realistically can,” but that’s not doable for everyone. That may work for people who have more or less regular routines, but not so much for those who live each day by the seat of their pants.

Instead, I’d tell you to follow the scientifically proven three-step process of habit formation— cue (or trigger), routine (or behavior) and reward, in that order. For example, the cue might come in the form of a set time per day to learn a language, the routine might be the language lesson itself and the reward might be a couple of chocolate bars conveniently stocked in your fridge. Those who have more erratic schedules can change the cue to “oh, the neighbor has stopped blasting rock music at three in the morning. Time to hit those flashcards!”

2. Be on the lookout for patterns in your target language

I’ve mentioned a couple of times before that the ability to recognize patterns partly answers the question “how do people learn languages?” Instead of studying your target language in isolation, try to relate it to the language you already know.

For example, if you’re studying a Germanic language like Dutch, you’re likely to find similar words in English. If you took up Latin in college, you may be pleasantly surprised to realize that Romance languages borrow heavily from their Latin ancestors.

Once you’re done checking out the similarities between languages, see if you can find any patterns within languages. For example, prefixes and suffixes usually change the meaning of a word in similar ways—e.g., in English, “pre-” indicates a word that refers to something that came before, while “post-” hints that the word is about something that came after or will come after. Languages are awesome, aren’t they?

3. Listen to native speakers of your target language in authentic contexts

Now, there’s nothing wrong with using audio programs specifically designed to teach languages. They’re essential to helping you master the nuts and bolts of the language, and I highly recommend them if you’re a beginner.

However, once you hit the intermediate or advanced stage, you’ll want to start exposing yourself to authentic audio materials. When you ask someone what their hobbies are in their native language, they’re not going to come at you with the canned, oversimplified answers language learning programs often provide. Instead, they’ll more likely launch into an entire TED Talk on why their favorite football (read: soccer) team is the best in the world, and you’ll have to respond accordingly if you want to have a meaningful conversation with them.

For this, you’d want to listen to podcasts in your target language. Even if you won’t be able to understand all (or even half) of what you’re listening to, you’ll still be consistently exposing yourself and your brain to the sounds, nuances and rhythm of your target language. Thanks to this constant exposure, you’ll eventually be able to pick up things like proper pronunciation, intonation and accent, and be able to express yourself beyond the stock phrases featured in textbooks.

4. Read authentic texts in your target language

Aside from training your ears, you’ll also want to train your eyes. How do the writers in your target language make use of vocabulary, grammar and figures of speech to convey what they want to say and elicit the right emotions in their audience? By reading as much of your target language as you can beyond formal “how to learn X language” textbooks, you can get a better feel for the different patterns, registers and rhythms of native speech in text form.

If you’re a beginner, you can start with children’s books in your target language (since they often use simple vocabulary and grammar) or translated books of tomes you’ve already read. Intermediate or advanced learners, on the other hand, can dive straight into original material, making sure to keep their foreign language dictionary handy or—to make things even more interesting—try to deduce as much as they can from context.

5. Use mnemonics

Earlier, I talked a bit about how babies learn their first words. When you say “Dada” or “Mama” and point to yourself, your baby makes the connection that the word and its corresponding sounds are somehow related to you, even if they still lack the capacity to explain why that is.

That’s what makes mnemonics so effective: They take advantage of the human ability to form associations between things that may or may not necessarily be related to each other.

For example, French learners often memorize the so-called “Vandertramp” verbs to figure out which verbs should use avoir (to have) and which ones should take on être (to be). And if you’re learning Spanish, here are some brilliant mnemonics you can swipe in case you’re having trouble with certain words or grammar points.

Of course, a mnemonic that works for one learner may not necessarily work for another. But that’s the beauty of mnemonics: They’re customizable to your needs! If you find that the mnemonics above don’t work for you, you can always change them or use a different mnemonic that’s more memorable.

6. Use games to learn languages

I cannot emphasize it enough: Language learning doesn’t have to be boring. In fact, studies have shown that educational computer games can be effective for learning foreign languages. Naturally, the study comes with the caveat that some games are better designed than others, and that if they’re not utilized the way they should be, they can be more distracting than helpful for language learning.

That caveat aside, there are plenty of language learning games you can play to suit your specific learning style. If you’re creative enough, you can also design your own game—like naming out loud at least 50 items in your house in your target language within 30 minutes.

7. Interact with speakers of your target language as much as possible

Again, social interaction with other human beings is key for effectively picking up a language. Not only will you learn the right way to respond in your target language and the finer things like pronunciation and accent, but it also fulfills your innate human need to socialize and belong in a group.

Start with language learning communities you can find online. You can also use sites like Meetup (or similar apps) to find like-minded individuals you can, well, meet up with in person. While in-person meetings can be inconvenient and aren’t always practical, they have the added benefit of teaching you body language across different cultures, so both online and offline options are great, actually!

8. Grab a language learning partner to help you out

If the idea of meeting a bunch of people scares you, but you don’t want to miss out on valuable social interactions either, take it one at a time—literally.

All you have to do is find a language exchange partner in-person or online. In case this is the first time you’re hearing the term “language exchange,” it’s exactly what it sounds like: You find someone who wants to learn your native language (e.g., English) in exchange for them teaching you their native language.

To make the most of this option, check out what other things your partner has to offer other than, say, “Spanish speaker looking for someone to teach me English.” Maybe they have the same interests and hobbies as you, or maybe your gut tells you that they’re just a great person to be with, period. One way or the other, you and your language fluency goals will benefit.

9. Think in your target language as much as possible

When you’re just starting to learn a language, it’s tempting to rely on the mental translation crutch—that is, thinking of what you want to say in your native language first before saying it out loud in your target language. The problem is that this becomes increasingly inefficient as the vocabulary and sentences you want to use become more complex and as you go higher up the language learning ladder.

To truly master a language, you need to think in it as much as possible. Name everyday items in your target language instead of your native one. If this sounds too difficult to do in practice, you can use mnemonics and Vocabulary Stickers to help you out. True to their name, Vocabulary Stickers consist of stickers with words in your target language, saving you the large amounts of time it would otherwise take to create these stickers from scratch.

10. Don’t be afraid to make mistakes

As I’ve mentioned earlier, making mistakes is an inevitable part of the language learning process.

Yes, saying mierda (fecal matter) when you meant to say miedo (afraid) will probably get you dirty looks from Spanish speakers, especially the more conservative ones. Then again, they might just laugh it off and give you a gentle correction instead. Either way, you learned something—and you’ll definitely never mix up these two confusing Spanish words ever again.

11. Remember to study the culture surrounding your target language, too

The more you study your target language, the more likely you’ll come across something like “you cannot study a language without studying its culture.” Indeed, there’s a strong relationship between language and culture in general.

For example, the various registers in East Asian languages like Japanese and Korean might seem perplexing to a native English speaker. But, when studied in the context of the highly collectivist societies that these languages operate in, they start to make sense: Weaving politeness into these languages is vital to maintaining social hierarchies and harmony between these hierarchies.

12. Watch authentic videos in your target language

When you’re reading or listening to speech, you don’t get the benefit of being able to watch native speakers sound out the words with their mouths. And if you watch your conversation partner’s mouth too closely while they’re talking—well, you can imagine how awkward that looks.

That’s where your last (but certainly not least) option comes in: Watch videos of the language being used in authentic contexts. You can get these videos anywhere, of course, but if you want those specially tailored for language learners, it’s hard to go wrong with a program like FluentU.

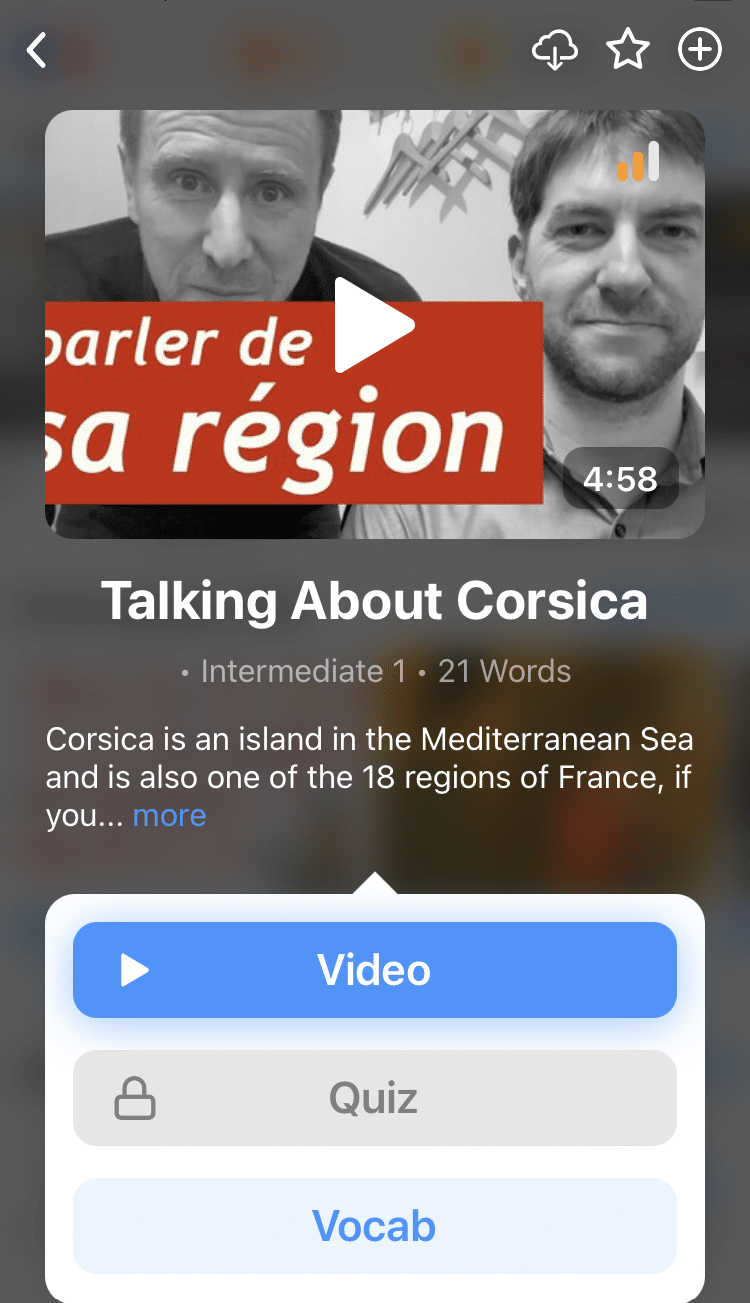

With FluentU, you hear languages in real-world contexts—the way that native speakers actually use them. Just a quick look will give you an idea of the variety of FluentU videos on offer:

FluentU really takes the grunt work out of learning languages, leaving you with nothing but engaging, effective and efficient learning. It’s already hand-picked the best videos for you and organized them by level and topic. All you have to do is choose any video that strikes your fancy to get started!

Each word in the interactive captions comes with a definition, audio, image, example sentences and more.

Access a complete interactive transcript of every video under the Dialogue tab, and easily review words and phrases from the video under Vocab.

You can use FluentU’s unique adaptive quizzes to learn the vocabulary and phrases from the video through fun questions and exercises. Just swipe left or right to see more examples of the word you're studying.

The program even keeps track of what you’re learning and tells you exactly when it’s time for review, giving you a 100% personalized experience.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

It’s true that there are important differences between how children and adults learn languages, and it’s clear that babies have some distinct advantages over older learners. However, adults also enjoy certain language learning advantages over their tiny counterparts.

Remember: Language is inherently human, and humans are always changing, meaning we can grow and reshape our brains when we want or need to for the sake of language acquisition.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)