How to Learn Japanese: Our 13 Favorite Tips for Beginners

Not everyone who learned to speak fluent Japanese studied in a classroom.

With all the resources available online these days, it’s easier than ever to learn Japanese on your own.

Take me, for example—I started from scratch and got to an advanced level with a realistic study plan, online courses, a notebook and some elbow grease.

Here, I’ll share 13 tips for how to learn Japanese as a beginner, along with some well-known expressions and helpful resources. Don’t worry—the art of teaching yourself is easily learned.

Contents

- 1. Start with pronunciation, core vocabulary and basic grammar

- 2. Set good goals and have realistic expectations

- 3. Learn Japanese that’s relevant and interesting to you

- 4. Prioritize specific language skills

- 5. Use movies and TV shows to learn

- 6. Listen to Japanese podcasts

- 7. Immerse yourself in Japanese language and culture

- 8. Vary your Japanese learning activities often

- 9. Practice active learning

- 10. Learn from your mistakes

- 11. Connect with Japanese learners and natives

- 12. Talk to yourself in Japanese

- 13. Study often (and don’t quit!)

- Common Expressions in Japanese

- Japanese Learning Resources

- And One More Thing...

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

1. Start with pronunciation, core vocabulary and basic grammar

First, you want to build your Japanese foundations.

Focus some time and energy on learning correct Japanese pronunciation. This video will teach you the basics in 14 minutes:

For more, you can learn the rules here and then practice some Japanese tongue twisters here.

Next, you’ll want to start building your core vocabulary in Japanese.

Think about the words you need for essential, everyday tasks. Words like hello, yes, please and thank you are good starting points. This post will help get you started and learn how to continue expanding your Japanese vocabulary.

Spending time right off the bat to familiarize yourself with basic Japanese grammar will also pay off in dividends.

Specifically, you’ll want to know simple Japanese sentence structure, the basics of Japanese verbs and how Japanese particles work.

2. Set good goals and have realistic expectations

Goal setting is really important if you’re striving to achieve fluency.

“I want to learn Japanese” just gives you way too much to work with, doesn’t it? When setting language learning goals, think about your past successes and what factors help and hinder you. Consider:

- your learning style

- topics that interest you

- having good sleep hygiene

- taking regular breaks

- learning with a tutor

- using rewards

Now, set some long-term goals to give your language journey meaning. Then, set short-term goals to help you hit those big milestones.

Track how you progress each month and review your goals regularly. You can use trackers such as those in this Language Printables resource to help.

Feeling unmotivated or burnt out can be a major hindrance, especially if you’re studying without peers and a teacher to encourage you. Find the balance between challenging yourself and expecting too much.

3. Learn Japanese that’s relevant and interesting to you

One huge benefit of learning a language on your own is relevance—you only need to learn what you want to learn.

You might be looking to learn how to speak Japanese for business or for travel, which means you can focus on those phrases and vocabulary.

In most cases, it will be helpful to learn set phrases like greetings and questions that Japanese speakers use on a daily basis. You can check out the “Common Expressions” section later in this post, and then continue learning essential Japanese phrases here.

Every learner wants to experience the rewards of studying Japanese. This is easy enough if you live in Japan, but even if you aren’t completely immersed in Japanese in your daily life, there are many ways to grow your confidence with the language.

Spending your study time on topics that interest you will provide the biggest returns. Pairing your passions with your Japanese learning will do wonders for your motivation.

You can watch Japanese dramas, read Japanese novels or even learn to play guitar from a Japanese YouTuber! Whatever you’re interested in, try using that to study the language.

4. Prioritize specific language skills

There’s a growing phenomenon of Japanese people forgetting how to handwrite kanji because they hardly ever have to.

These days, so much of our writing takes place on phones and computers. Of course you’ll need to learn to write the Japanese kana, but over 2,000 kanji?

With your limited study time (and so much to learn before achieving fluency), consider putting handwriting on the back burner and focusing instead on the skills that’ll add more immediate value to your Japanese studies.

Use your reclaimed time to read more, listen more, talk more—basically, practice using the language in ways that will really help you communicate.

Eventually, you will need to learn how to handwrite at least some kanji, but you can make immense progress by prioritizing your listening and speaking skills first. This will allow you to start asking questions and making connections right away.

If you don’t have anyone to practice speaking with yet, it’s a good idea to make a few Japanese friends. One great way to connect with Japanese speakers is through language exchange, where you can get to know each other and help each other learn.

5. Use movies and TV shows to learn

Consuming entertainment media is a fun way to practice your Japanese listening skills and overall comprehension.

Authentic content is essential for learning real Japanese. Real-world conversations are full of slang and colloquialisms that you will only find when consuming native materials.

A good place to start is to watch Japanese movies with subtitles. You’ll learn how to piece together what you know and make sense of what you don’t. You can always split movies into smaller segments at first.

Another option is to learn Japanese with anime programs, but these often use a unique speech style that differs from everyday Japanese.

You can also use Japanese TV shows to learn. They often discuss news stories and interview guests in fast-paced, everyday Japanese—because they’re intended for Japanese people. If you can follow talk shows, then your listening skills are already very good.

No matter what you enjoy watching, there will be something in Japanese suited to your interests. Check out the Resources section below for places you can find Japanese movies and television programming.

6. Listen to Japanese podcasts

There are podcasts in every language and on every topic, so this offers a great way to immerse yourself in Japanese. Keep in mind that you don’t have to limit yourself to Japanese language learning podcasts.

You can listen to news, sports, talk shows, comedy and any other genre in Japanese.

Simply change your iTunes settings to Japanese using these steps:

- Open iTunes and go to the iTunes Store.

- Scroll to the bottom, and select “Change Country” under “Manage.”

- Select “Japan.”

- Now you can see the content that’s popular in Japan—in Japanese!

7. Immerse yourself in Japanese language and culture

If you aren’t quite up to speed yet, watching Japanese movies and TV can be frustrating.

When this happens, you’ll benefit from extra tools and support to help you watch Japanese media, like language immersion programs.

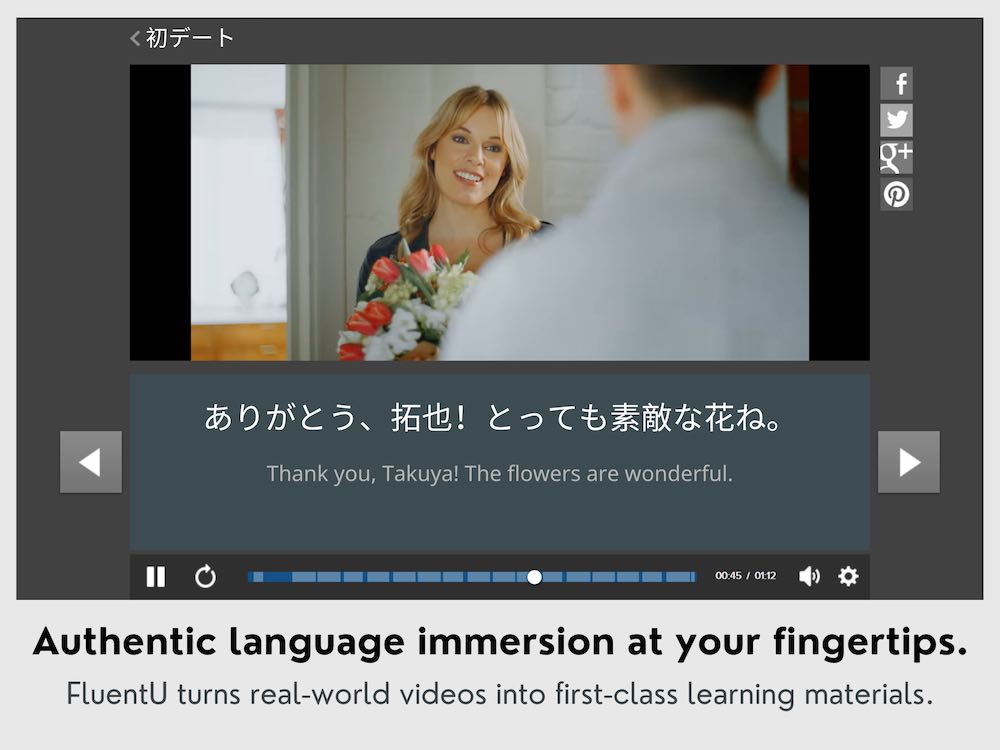

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

The important thing with immersive studying is to surround yourself with Japanese for a certain amount of time every week. Make it a Japanese-only time, where everything you do—from checking your phone to writing your shopping list—is in Japanese.

Avoid distractions in your native language by using a focus app for your cell phone, a clock or a kitchen timer. You can also practice switching your internal dialogue to Japanese—try to think more in pictures, not words.

A final way to immerse yourself in Japanese is to switch the language settings of your electronics to Japanese. This lets you manage your schedule, set your alarms, check your voicemail and get updates in Japanese instead of English.

Here’s a bonus tip: You can also now practice your Japanese any time with Siri if you can’t find a local speaking partner!

8. Vary your Japanese learning activities often

This will help keep your studying from feeling stale or boring. Here are some exercises you can try:

- Narrate your life in Japanese. This is pretty much just talking to yourself, but it’s a great way to keep your speaking skills sharp.

- Learn with Japanese songs. Figure out how to learn a language with music, and soon you’ll have a lot more Japanese stuck in your head. You can find a listing of the Japanese pop charts here and then search for the songs on YouTube. Looking up Japanese song lyrics is a breeze with this useful guide. You could also stream live radio from Japanese stations on sites like Live365.

- Cook with Japanese recipes. You’ll learn lots of useful nouns, verbs and adjectives while massively upping your cooking game. Learning with your hands will help make the language stick, too. Check out Harumi Kurihara and her collection of Japanese-language recipes.

- Translate Japanese reading materials. Translating is an effective learning technique because it quickly reveals where your language weaknesses lie. I recommend doing this in short segments to avoid getting overwhelmed.

- Study with Japanese manga. There’s a manga for pretty much every subject out there. This is a fun way to pick up on Japanese slang and colloquialisms in a pressure-free environment. You can find titles to purchase on Kinokuniya.

- Practice Japanese with the “scriptorium” method. Developed by Alexander Arguelles, this exercise helps you practice reading and writing as well as speaking and understanding. Say a Japanese sentence aloud, write it out while saying it again, then read it aloud from what you’ve written. You can read more about this practice here.

- Shadow native Japanese speakers. Ideally you’ll want written and audio versions of the same material. Listen to the audio while reading the sentence, then speak it immediately after while mimicking the speaker as closely as possible.

Using a variety of study activities (especially ones you enjoy!) makes learning Japanese faster and more fun. You can even get the most out of your learning tools by using them to develop multiple language skills at the same time!

Shadowing with audio and text strengthens your listening, reading and speaking skills all at once, for example. Finding ways to combine practice for listening, speaking, reading and writing, as well as vocabulary and grammar, will really help you learn efficiently.

9. Practice active learning

Without looking it up, draw the Apple logo. You must have seen it hundreds of times, right? Now check the real logo against your drawing.

The Universe of Memory goes into this experiment in more detail to explain why simply being exposed to something repeatedly isn’t enough to remember it.

The applications for language learning are pretty clear.

Active learning—rather than passive exposure—is the best way to form strong memories and recall new information. Take a look at this video for more information:

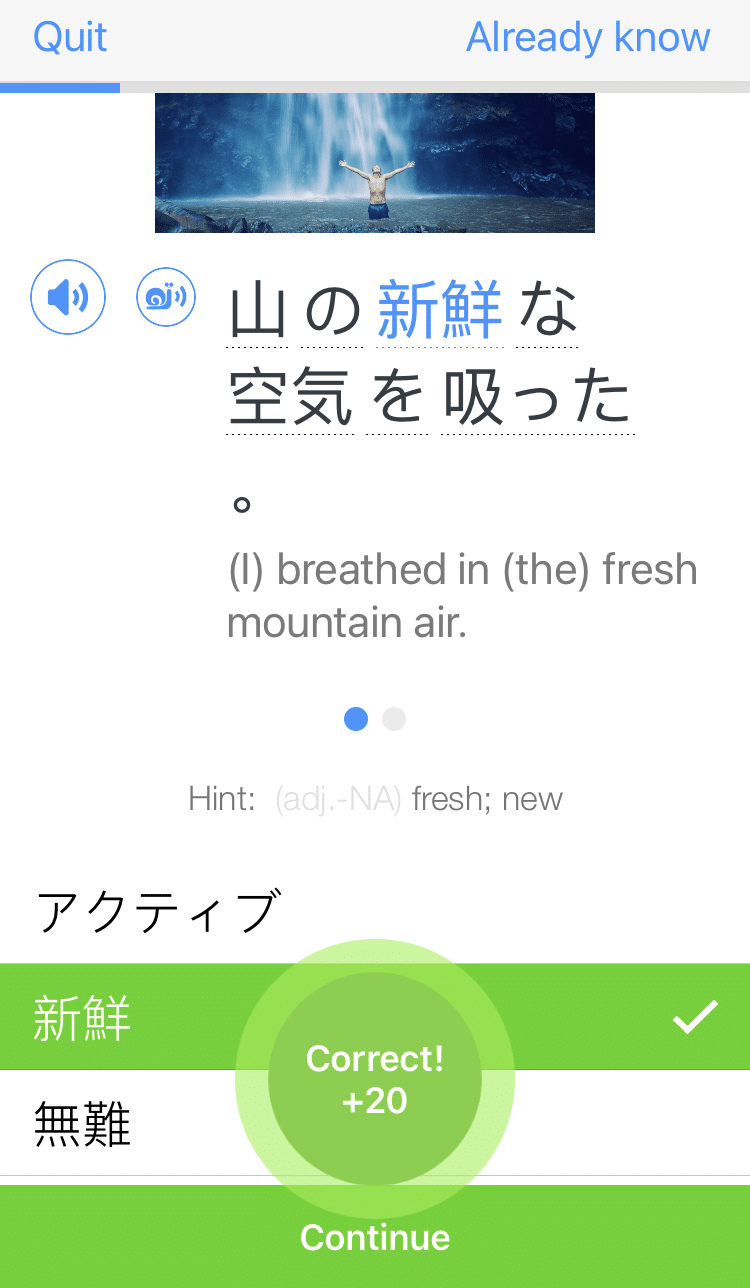

Some strategies that promote active learning are shadowing, quizzing yourself, using SRS programs and applying your learning in conversations.

Reflecting upon learning and asking questions as you learn will also strengthen your memories and make your routine more active. Other strategies to boost active learning include re-phrasing and summarizing content.

Research indicates that we find learning and recall easier when the topic connects to something we already know. When studying Japanese, take some time to consider how a new topic links with your prior learning to strengthen your neural connections.

To do this, simply ask yourself these questions before or after you study:

- What do I know already?

- What do I want to know?

- What did I learn?

10. Learn from your mistakes

Mistakes can be uncomfortable, but they’re a natural part of language learning.

When we learned to speak our native languages as children, we did it through repeated trial and error until we were understood. We had adults helping to correct our mistakes, too.

Now, as adults ourselves, we can support our own learning by recognizing our mistakes and using them to point us toward areas where we need to focus our efforts.

Move away from thinking that mistakes are bad or shameful. Reframing the common mindset about mistakes can really help boost motivation and reduce feelings of failure or frustration.

If we understand and do everything perfectly when learning something new, then we aren’t being adequately challenged!

The five-finger rule is helpful for finding materials at your level when learning Japanese. Open a new reading book (not a textbook) or some Japanese short stories to any page, and start counting the number of words you don’t understand:

- 0-1 unknown words: This text is too easy; you won’t be adequately challenged.

- 2-3 unknown words: This text is just right; you can read it and learn something new without getting lost.

- 4 unknown words: This text will be a challenge; try it if you’re feeling ambitious!

- 5+ unknown words: This text is too difficult for you right now.

Remember: noting mistakes, studying the material again and reviewing regularly until you no longer make those mistakes is the best way to improve your Japanese.

11. Connect with Japanese learners and natives

Learning with friends can make improving your Japanese more fun than hard work. Check out resources like Meetup, your local university’s Japanese societies, community center events or language classes to find other people who are learning Japanese.

You can also check out what your nearest Japanese embassy is doing to promote Japanese language and culture in your area.

Beyond meeting other learners or people who enjoy Japanese culture, it’s also likely you’ll meet native Japanese speakers at many of these events.

Connecting with fellow learners can give you a community to share study tips with, while connecting with native speakers can offer more cultural insights and authentic practice opportunities with the language. Plus, it’s a great way to make new friends!

12. Talk to yourself in Japanese

Yes, sometimes you have to look like a crazy person to master a foreign language!

Get into the habit of talking to yourself in Japanese. People often recommend narrating what you’re doing, such as saying:

歯を磨いている。鏡を見ている。

(はをみがいている。かがみをみている。

I’m brushing my teeth. I’m looking in the mirror.

But I think this is weird because no one does this in English (I hope).

But what about that dialogue most of us have constantly running through our heads? When you catch yourself thinking about something, turn it into Japanese!

13. Study often (and don’t quit!)

Little and often is better than occasional marathon learning. One long session a week won’t pay off as much as short practice every day.

This is partly due to the mechanics of remembering and forgetting. Waiting too long between study sessions runs the risk of needing to re-learn old material, interrupting your previous efforts.

This is where a spaced repetition system (SRS) comes in handy. Many online flashcard sites use SRS to help maximize learning. You’ll see your Japanese vocab words right when you’re about to forget them, helping strengthen the mental bond.

Of course, this “study often” technique means you have to avoid procrastination. If you’re a serial procrastinator, then apps and plugins may help you break the habit and build a good study routine.

Another good strategy is to integrate learning into time that’s otherwise wasted. Studying while you commute, queue at the bank or brush your teeth can help you find extra minutes you didn’t even realize you had!

You will have days when you just don’t feel like studying, and that’s okay—it happens to everyone. But the key to successfully learning Japanese is to keep at it no matter what.

An open secret among successful language learners is that self-discipline steps in where motivation fails you. A good routine—like reviewing your vocabulary every morning at breakfast—can help language learning become second nature.

So, keep at it. You’re on the right track already!

Common Expressions in Japanese

A great way to start learning a new language is to master some everyday expressions.

With just a few good Japanese sentences, you can come across as relatively knowledgeable, even to a native speaker. But more importantly, you can find your way to the bathroom if you find yourself in a pinch.

Greetings

私の名前はブルースです。どうぞ宜しくお願いします。

(わたしの なまえは ぶるーす です。どうぞ よろしく おねがいします。)

My name is Bruce. Please treat me well.

おはようございます!

Good morning!

こんにちは!

Good day!

こんばんは!

Good evening!

お元気ですか?

(おげんき ですか?)

How are you?

Questions

これ / それ / あれは何ですか?

(これ/それ/あれは なん ですか?)

What is this/that/that over there?

この / その / あの人は誰ですか?

(この/その/あのひとは だれ ですか?)

Who is this/that/that person over there?

トイレはどこですか?

(といれは どこ ですか?)

Where is the toilet?

今は何時ですか?

(いまは なんじ ですか?)

What time is it?

何?

(なに?)

What?

Statements

私は寿司 / チョコレート / ビールが好きです。

(わたしは すし/ちょこれーと/びーるがすき です。)

I like sushi/chocolate/beer.

私は雑音 / タバコ / 月曜日が嫌いです。

(わたしは ざつおん/たばこ/げつようびが きらい です。)

I hate noise/tobacco/Mondays.

すみません。

Excuse me.

ありがとうございます。

Thank you very much.

また明日!

(また あした!)

See you tomorrow!

元気でね。

(げんき でね。)

Stay well.

Japanese Learning Resources

Using reputable, well-known resources for learning Japanese will help you make the most of your study time.

For apps and language learning software, you can check out:

- Duolingo — for bite-sized lessons that build up vocabulary and grammar knowledge for a solid foundation of Japanese. Read our full review here.

- FluentU — for immersive, authentic Japanese language videos, personalized quizzes and an SRS flashcard system.

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

- Memrise — for SRS and user-made visual mnemonics that pairs new vocabulary with exercises and Japanese videos. Read our full review here.

- LingoDeer — for quick lessons that teach foundational Japanese grammar and help you build vocabulary naturally. Read our full review here.

- Anki — for SRS flashcards, pre-made vocabulary decks and top-notch sorting and reviewing tools. Read our full review here.

- Pimsleur — for a dialogue-based learning experience with a heavy focus on speaking and especially on listening. Read our full review here.

- Rosetta Stone — for a classic language program to help you learn how to read, listen and speak in Japanese. Read our full review here.

- More options on this list!

For textbooks, you might like:

- “Genki I” — a short, to-the-point book that’s ideal for those with limited time who still want to learn the basics.

- “Minna no Nihongo” — a thorough text that’s ideal for serious learners ready to dedicate significant time to studying.

- More options that you can read about in this round-up of Japanese textbooks.

For TV and movies, you can access:

- Crunchyroll — has a huge collection of anime.

- AsianCrush — home to hundreds of TV shows, movies and web videos.

- Netflix — may have any number of Japanese titles based on your region and what’s available.

If you read this whole post, that probably means you’re dedicated to learning Japanese.

And now that you know how to learn Japanese—good luck! You can do this!

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing...

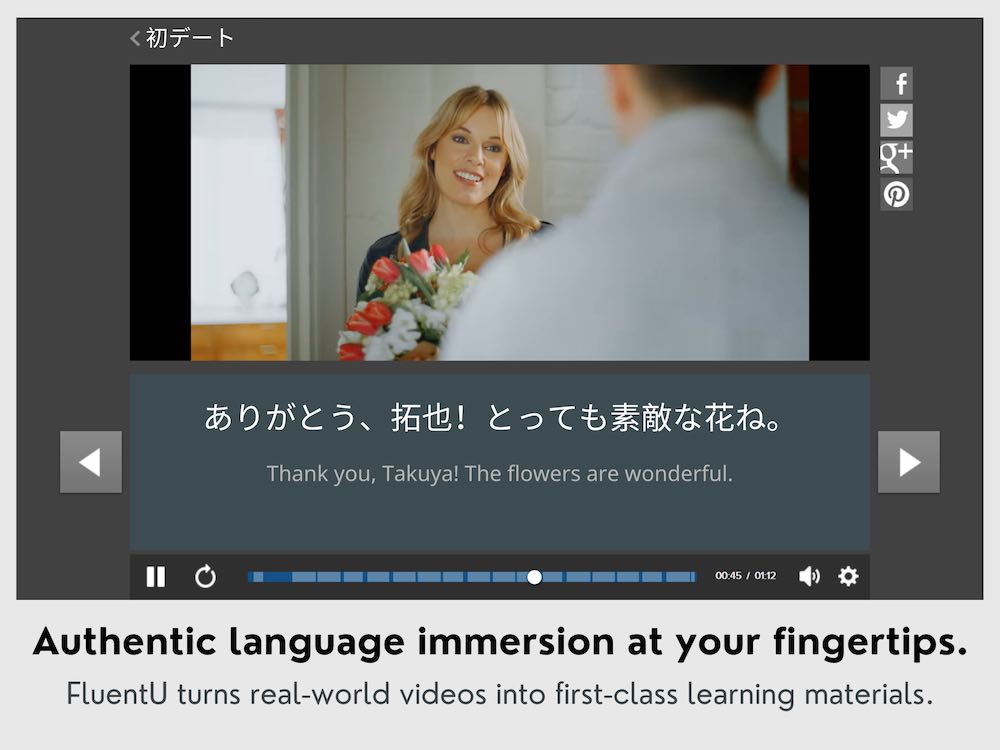

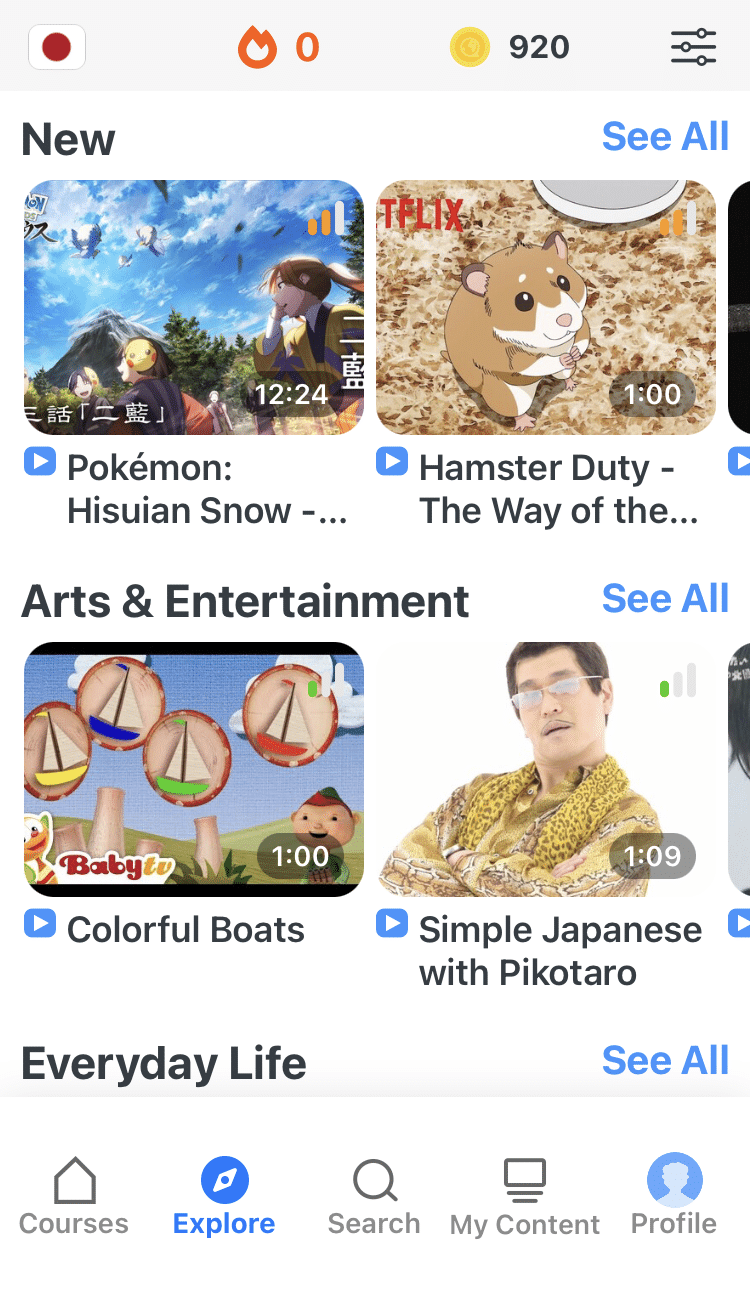

If you love learning Japanese with authentic materials, then I should also tell you more about FluentU.

FluentU naturally and gradually eases you into learning Japanese language and culture. You'll learn real Japanese as it's spoken in real life.

FluentU has a broad range of contemporary videos as you'll see below:

FluentU makes these native Japanese videos approachable through interactive transcripts. Tap on any word to look it up instantly.

All definitions have multiple examples, and they're written for Japanese learners like you. Tap to add words you'd like to review to a vocab list.

And FluentU has a learn mode which turns every video into a language learning lesson. You can always swipe left or right to see more examples.

The best part? FluentU keeps track of your vocabulary, and gives you extra practice with difficult words. It'll even remind you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. You'll have a 100% personalized experience.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)