41 Important Japanese Honorifics and How to Use Them

Japanese honorifics are a complex system of addressing other people, much like the “Mr./Sir” and “Ms./Madame” in English.

And just like their English counterparts, there are instances where you can use them—and ones where you can’t.

Read on to learn more about the most common Japanese honorifics. Some of them you may have heard of, while others may surprise you.

Let’s go!

Contents

- 1. さん — San

- 2. 君 ( くん ) — Kun

- 3. ちゃん — Chan

- 4. 氏 (し) — Shi

- 5. 様 ( さま ) — Sama

- 6. 先輩 (せんぱい) — Senpai

- 7. 先生 (せんせい) — Sensei

- 8. 殿 ( どの ) — Dono

- 9. 父 (ちち) / お父さん (おとうさん) — Father / Dad

- 10. 母 (はは) / お母さん (おかあさん) — Mother / Mom

- 11. おじさん (Uncle)

- 12. おばさん (Aunt)

- 13. おじいさん (Grandpa)

- 14. おばあさん (Grandma)

- 15. 兄 ( あに ) / お兄さん (おにいさん) — Big Brother

- 16. 姉 (あね) / お姉さん (おねえさん) — Big Sister

- 17. 弟 (おとうと) — Younger Brother

- 18. 妹 (いもうと) — Younger Sister

- 19. 社長 (しゃちょう) — President

- 20. 副社長 (ふくしゃちょう) — Vice President

- 21. 部長 (ぶちょう) — Department Head

- 22. 課長 (かちょう) — Section Head

- 23. 係長 (かかりちょう) — Team Leader

- 24. 弊社 (へいしゃ) — “Our Company” (Humble)

- 25. 自社 (じしゃ) — “Our Company” (Neutral)

- 26. 貴社 (きしゃ) — “Your Honorable Company” (Written)

- 27. 御社 ( おんしゃ ) — “Your Honorable Company” (Spoken)

- 28. 当社 (とうしゃ) — “Our/Your/This Company” (Neutral)

- 29. 剣聖 (けんせい) — Master Swordsman

- 30. 親方 (おやかた) — Sumo Coach

- 31. 師匠 (ししょう) — Martial Arts Coach

- 32. 関 (せき) — High-ranking Sumo Wrestlers

- 33. 法師 (ほうし) — Buddhist Monk

- 34. 神父 (しんぷ) — Catholic Priest

- 35. 牧師 (ぼくし) — Protestant Pastor

- 36. 陛下 (へいか) —Your Majesty

- 37. 殿下 (でんか) — Your Highness

- 38. 王女 (おうじょ) / 姫 (ひめ) — Princess

- 39. 王子 (おうじ) — Prince

- 40. 閣下 (かっか) — Your Excellency

- 41. 大統領 (だいとうりょう) — President

- How to Use Japanese Honorifics

- And One More Thing...

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

1. さん — San

Ahhh, the famous さん. It’s arguably the most common Japanese honorific.

That’s because it’s used in both formal and informal situations. It’s generally okay to use for anyone, especially when you’re not sure which honorific to go for.

彼は鈴木さんです。 (かれは すずきさん です。) — He is Suzuki-san.

さん can also be used to refer to companies and shops to imply respect for whatever that establishment itself may be, as well as the people who might be representing it.

It’s really quite a versatile honorific. You can use it to refer to your dog, your favorite animated character/bag/food or even the Easter Bunny! You can give a toy bear to a child and say:

これはくまさんです! (This is Mr. Bear!)

In the wonderful world of さん, you might even be able to use it while cooking:

鍋にエビさんとカニさんをいっぱい入れましょう! (なべにえびさんとかにさんをいっぱいいれましょう!) ー Let’s put plenty of Mr. Shrimp and Mr. Crab into the pot!

2. 君 ( くん ) — Kun

You might have heard 君 in an anime, usually referring to a boy of school age.

君 is generally used to address young males. It can also be used for any man (or sometimes woman!) who entered a company after the person addressing them.

お疲れ様、明日の会議の資料を作成してくれるかい、田中くん? (おつかれさま、あすのかいぎのしりょうをさくせいしてくれるかい、たなかくん?) — Good job, Tanaka-kun, could you prepare the materials for tomorrow’s meeting?

It can also be used by women when they speak of their boyfriends, husbands or really close male friends. There are a lot of times when you’ll hear a woman attach 君 with a certain fondness behind her words.

3. ちゃん — Chan

ちゃん is one funny honorific. It often refers to people, things or animals that are adorable, sweet or endearing.

It’s usually used to address or talk about babies, young boys and girls, teenage girls, girlfriends, boyfriends or even a male friend that you find to be kind of cheeky and too close to warrant a さん.

Don’t use it with a superior or a not-too-close male friend, though—unless you want to get fired or punched!

今日は一緒に遊びましょうね、さくらちゃん! (きょうはいっしょにあそびましょうね、さくらちゃん!) — Let’s play together today, Sakura-chan!

4. 氏 (し) — Shi

You’re not going to encounter 氏 often out loud, but it’s actually a common honorific in writing.

It’s used mainly in the news when talking or writing about a famous person or notable figure (or really, anyone in the news) that one doesn’t know personally. It can also be used instead of a pronoun once the person in question has been established.

Keep this in mind when you’re studying your newspaper kanji!

今年の講演会には、有名な心理学者、田村氏が出席します。 (ことしのこうえんかいには、ゆうめいなしんりがくしゃ、たむらし がしゅっせきします。) — This year’s lecture will be attended by the renowned psychologist, Mr. Tamura.

5. 様 ( さま ) — Sama

様 is a more formal version of さん.

It’s usually used to refer to customers, those of higher rank or someone who’s earned (or just warrants) your respect. Customers of any kind of shop or service are automatically given the “utmost respect” status, so you’ll certainly have heard this if you’ve ever gone shopping in Japan.

You may have already encountered it in common Japanese phrases such as お疲れ様 (おつかれさま) — “good work” and ご苦労様 (ごくろうさま) — “thank you for doing this work for me”.

In period dramas, or if you’re visiting the home of a martial artist, you may also hear 上 (うえ) which literally means “above.” So you may hear someone’s father referred to as 父上 ( ちちうえ ). But this is quite rare (or even outdated), which is why I didn’t include a separate entry for it.

For now though, just stick to 様 for companies and respected people, and you’ll be off to a great start.

お越しいただき、ありがとうございます。皆様にとって有益な情報をお伝えいたします。 (おこしいただき、ありがとうございます。みなさまにとってゆうえきなじょうほうをおつたえいたします。) — Thank you for coming. Everyone, I will share valuable information with all of you.

6. 先輩 (せんぱい) — Senpai

Another honorific heavily used in anime and Japanese series, 先輩 is used to address a senior in your school, work, club or any other group you might belong to. For example, if you’re a sophomore, a freshman in your college is going to call you 先輩.

Also, you won’t necessarily need a name to use 先輩. It’s an honorific that can stand on its own.

The opposite of 先輩, which is 後輩 (こうはい) — junior, is going to sound super condescending if used to refer to someone—with or without a name. I’d stay away from ever using that as a suffix!

おはようございます、先輩。 (おはようございます、せんぱい。) — Good morning, Senpai.

7. 先生 (せんせい) — Sensei

You might already know that this one is used to refer to teachers, but 先生 is also used to address people in general who are experts in their respective fields.

It can refer to people of science (doctors, biologists, physicists), the arts (novelists, painters, musicians, manga artists), law and politics (politicians, lawyers, judges) and masters of martial arts.

Like 先輩, it can be used as a stand-alone title—and is so often used this way that you may actually forget the real name of whoever you’re referring to!

先生、質問があります。 (せんせい、しつもんがあります。) — Sensei, I have a question.

8. 殿 ( どの ) — Dono

殿 is a tricky little honorific that’s usually used when the person you’re referring to is at the same level as you, but needs to be shown a bit more respect than usual.

Not commonly used, it roughly has the meaning of “master” or “lord,” but it’s definitely not used in that context anymore for obvious reasons.

田中殿、ご協力いただき、誠にありがとうございます。 (たなかどの、ごきょうりょくいただき、まことにありがとうございます。) — Mr. Tanaka, thank you very much for your cooperation.

9. 父 (ちち) / お父さん (おとうさん) — Father / Dad

This is pretty standard, but can be exchanged for a lot of variations depending on your relationship. 親父 (おやじ) — “dad” or “old man” can be used affectionately or somewhat rudely to refer to an older gentleman. Careful!

お父さん、お仕事お疲れ様です。 (おとうさん、おしごとおつかれさまです。) — Father, thank you for your hard work.

10. 母 (はは) / お母さん (おかあさん) — Mother / Mom

A lot of the time, you can drop the お prefix when speaking to your own mother.

お母さん、これは美味しいですね。 (おかあさん、これはおいしいですね。) — Mother, this is delicious, isn’t it?

11. おじさん (Uncle)

You can also use this one to describe an older man you may or may not know—but be careful! You don’t want to call a 30-something an “old man” and ruin someone’s day.

Another variation to watch out for is the rude おっさん (something like “geezer”).

おじさん、お元気ですか? (おじさん、おげんきですか?) — Uncle, how are you?

12. おばさん (Aunt)

You might have heard people in TV shows using this for women they don’t know but perceive to be older women. You can imagine how much trouble this could get you into!

おばさん、お手伝いしましょうか? (おばさん、おてつだいしましょうか?) — Aunt, shall I help?

13. おじいさん (Grandpa)

I’d save this one for people who are obviously senior citizens, if used at all. But using it with your own grandfather is fine. If you want to refer to someone else’s grandfather, use 祖父 (そふ).

おじいさん、今日も元気ですね。 (おじいさん、きょうもげんきですね。) — Grandfather, you seem energetic today, too.

14. おばあさん (Grandma)

The rules that apply to “grandfather” apply to this one as well. If you want to talk about someone else’s grandmother, use 祖母 (そぼ).

おばあさん、昔話を聞かせてください。 (おばあさん、むかしばなしをきかせてください。) — Grandma, please tell me a bedtime story.

15. 兄 ( あに ) / お兄さん (おにいさん) — Big Brother

Use this for your (or someone’s) actual brother, or just a young man whose name you don’t know.

お兄さん、何してるの? (おにいさん、なにしてるの?) — Big brother, what are you doing?

16. 姉 (あね) / お姉さん (おねえさん) — Big Sister

Again, the rules that apply to older brothers also apply to this one. お姉さん is also used to refer to young women. I’d opt for this one as opposed to おばさん if you want to be polite.

お姉さん、今度の週末、一緒に買い物に行きませんか? (おねえさん、こんどのしゅうまつ、いっしょにかいものにいきませんか?) — Big sister, would you like to go shopping together this weekend?

17. 弟 (おとうと) — Younger Brother

You can use this to refer to your own younger brother or someone else’s younger brother.

田中さんの弟は高校生です。 (たなかさんのおとうとはこうこうせいです。) — Mr. Tanaka’s younger brother is a high school student.

18. 妹 (いもうと) — Younger Sister

The same rules above apply here: 妹 can refer to your younger sister or someone else’s.

山田さんの妹は大学で中国語を勉強しています。 (やまださんのいもうとはだいがくでちゅうごくごをべんきょうしています。) — Ms. Yamada’s younger sister is studying Chinese at university.

Some notes on using honorifics within families:

- As mentioned earlier, the お at the beginning of the title can be dropped if the conversation is casual. You’ve probably even heard older brothers or sisters simply referred to as 兄ちゃん (にいちゃん) or 姉ちゃん (ねえちゃん).

- The use of honorifics within the family generally adheres to a hierarchical order. The younger members of the family will address an older member using an honorific. In the opposite direction (older to younger), calling by name is acceptable.

- If a younger member of the family is present, honorifics will shift. For instance, if we have a household of three generations, the father will call his father “grandpa” or おじいさん and his wife “mother” or お母さん in front of the children.

19. 社長 (しゃちょう) — President

This refers to the president or chief executive officer (CEO) of a company.

社長、今月の予算報告です。 (しゃちょう、こんげつのよさんほうこくです。) — President, here is this month’s budget report.

20. 副社長 (ふくしゃちょう) — Vice President

Also translated as “Deputy President,” the 副社長 is second in rank to the President or CEO and helps the latter manage the company’s affairs.

副社長、次の会議のアジェンダを確認しました。 (ふくしゃちょう、つぎのかいぎのあじぇんだをかくにんしました。) — Vice President, I’ve confirmed the agenda for the next meeting.

21. 部長 (ぶちょう) — Department Head

The 部長 is in charge of a specific department within a company. You can easily tell which department someone is managing based on the word before 部長, such as 営業部長 (えいぎょうぶちょう) — head of the sales department or 人事部長 (じんじぶちょう) — head of the human resources department.

部長、新メンバーの導入について意見を聞かせてください。 (ぶちょう、しんめんばーのどうにゅうについていけんをきかせてください。) — Department Head, please share your opinions on the introduction of new members.

22. 課長 (かちょう) — Section Head

The 課長 is a level below the 部長. They’re responsible for managing and supervising the team within their designated section in the department.

課長、プロジェクトの進捗状況を報告していただけますか? (かちょう、ぷろじぇくとのしんちょくじょうきょうをほうこくしていただけますか?) — Section Chief, could you report on the progress of the project?

23. 係長 (かかりちょう) — Team Leader

The 係長, in turn, ranks below the 課長. They’re responsible for managing their designated unit within their section.

新しいプロジェクトの進捗管理は、係長の責任です。 (あたらしいぷろじぇくとのしんちょくかんりは、かかりちょうのせきにんです。) — It’s the responsibility of the team leader to manage the progress of the new project.

24. 弊社 (へいしゃ) — “Our Company” (Humble)

弊社 is a humble or modest way of referring to one’s own company. The use of 弊 (へい) adds a sense of self-deprecation or humility. It’s commonly used in business communication, documents or formal situations when talking about the company to parties outside the company.

弊社のビジョンは、革新的なテクノロジーを活用し、社会に貢献することです。 (へいしゃのびじょんは、かくしんてきなてくのろじーをかつようし、しゃかいにこうけんすることです。) — Our company’s vision is to leverage innovative technology and contribute to society.

25. 自社 (じしゃ) — “Our Company” (Neutral)

自社 is a more neutral (and literal) way to refer to one’s own company. As you know, 自 (じ) means “self” or “own,” while 社 (しゃ) means “company” or “firm.”

It’s often used in business contexts when discussing anything related to one’s own company, products or services. For example, 自社製品 (じしゃせいひん) would mean “in-house products” or products manufactured by one’s own company.

自社製品の品質管理は非常に厳格です。 (じしゃせいひんのひんしつかんりはひじょうにげんかくです。) — The quality control of our in-house products is extremely rigorous.

26. 貴社 (きしゃ) — “Your Honorable Company” (Written)

貴社 is a polite and respectful way to refer to another person’s or another company’s business. You’ll usually see it in formal written communication like business letters.

貴社の提案に感謝しています。 (きしゃのていあんにかんしゃしています。) — We appreciate your company’s proposal.

27. 御社 ( おんしゃ ) — “Your Honorable Company” (Spoken)

御社 is similar to 貴社, though you’ll more often hear the former in formal conversations when addressing or mentioning another company with a high level of respect.

御社の担当者にお伝えください。 ( おんしゃのたんとうしゃにおつたえください。 ) — Please convey it to your company’s representative.

28. 当社 (とうしゃ) — “Our/Your/This Company” (Neutral)

当社 can be either “our company”, “your company” or “this company”.

当社の取締役会は、次世代技術の導入について議論しています。 (とうしゃのとりしまりやくかいは、じせだいぎじゅつのどうにゅうについてぎろんしています。) — Our company’s board of directors is discussing the implementation of next-generation technologies.

29. 剣聖 (けんせい) — Master Swordsman

剣聖 literally translates to “Sword Saint.” As you might’ve guessed, it refers to someone who has a legendary or near-legendary level of swordsmanship.

剣聖、お見事な剣術ですね。 (けんせい、おみごとなけんじゅつですね。) — Master, your swordsmanship is splendid.

30. 親方 (おやかた) — Sumo Coach

In the context of sumo wrestling, 親方 refers to a stablemaster or coach. He’s usually a retired sumo wrestler himself who’s reached a certain rank and is now responsible for running the stable and training the wrestlers.

It can also be a broad term for “mentor,” especially in traditional Japanese crafts and apprenticeship systems.

親方、弟子たちが準備完了しました。 (おやかた、でしたちがじゅんびかんりょうしました。) — Master, the disciples are ready.

31. 師匠 (ししょう) — Martial Arts Coach

In many traditional martial arts, addressing an instructor as 師匠 is a formal and respectful way of acknowledging their role as a guide in the practitioner’s martial arts journey. The term is commonly used in various Japanese martial arts disciplines such as karate and judo.

師匠、私にもっと教えてください。 (ししょう、わたしにもっとおしえてください。) — Master, please teach me more.

32. 関 (せき) — High-ranking Sumo Wrestlers

In the context of sumo wrestling, 関 refers to high-ranking sumo wrestlers, including the rank of 横綱 (よこずな). 横綱 is the grand champion of sumo, and the title is the highest achievable rank in the sport.

彼は今や相撲界の頂点に立つ、まさに関の地位にふさわしい存在です。 (かれはいまやすもうかいのちょうてんにたつ、まさにせきのちいにふさわしいそんざいです。) — He now stands at the pinnacle of the sumo world, truly deserving of the status of Yokozuna.

33. 法師 (ほうし) — Buddhist Monk

This term can be used broadly to describe Buddhist clergy in general, rather than just monks.

法師様、私たちに祈りを捧げてください。 (ほうしさま、わたしたちにいのりをささげてください。) — Monk-sama, please offer prayers for us.

34. 神父 (しんぷ) — Catholic Priest

神父 literally means “god father” and is used to address or refer to Catholic priests in Japan.

神父、結婚式を執り行います。 (しんぷ、けっこんしきをとりおこないます。) — Father, we will hold the wedding ceremony.

35. 牧師 (ぼくし) — Protestant Pastor

If you’re wondering how Protestant pastors are referred to in Japan, 牧師 is the usual term for it.

牧師さん、お世話になっています。 (ぼくしさん、おせわになっています。) — Pastor-san, thank you for taking care of us.

36. 陛下 (へいか) —Your Majesty

This is used after the titles “Emperor” or “Empress.” You’ll likely see this in reports regarding the goings-on of the Imperial family.

陛下、お待ちしておりました。 (へいか、おまちしておりました。) — Your Majesty, we have been waiting for you.

37. 殿下 (でんか) — Your Highness

This is used after other titles like “King” or “Queen” to mean something similar to “his/her Highness”

殿下、ご機嫌いかがですか? (でんか、ごきげんいかがですか?) — Your Highness, how are you feeling?

38. 王女 (おうじょ) / 姫 (ひめ) — Princess

If you ever happen to be in the presence of a princess (or you’re joking around with a girl you’re trying to impress), this honorific is your friend.

王女様、お忙しい中ありがとうございます。 (おうじょさま、おいそがしいなかありがとうございます。) — Princess-sama, thank you for taking the time in your busy schedule.

39. 王子 (おうじ) — Prince

You may have heard this one in Japanese dramas or anime. It’s either affixed with 様 as in 王子様 (おうじさま) for “Prince Charming,” or it’s tacked on to a name, such as ハリー王子 (はりーおうじ) for “Prince Harry.”

王子様は、王国の未来を担う重要な役割を果たしています。 (おうじさまは、おうこくのみらいをになうじゅうようなやくわりをはたしています。) — The prince is playing a crucial role in shaping the future of the kingdom.

40. 閣下 (かっか) — Your Excellency

This is used for Prime Ministers, ambassadors, etc.

閣下、この計画に関するご意見をお聞かせいただけますか? (かっか、このけいかくにかんするごいけんをおきかせいただけますか?) — Your Excellency, could you please share your opinions on this plan?

41. 大統領 (だいとうりょう) — President

On the other hand, 大統領 is for presidents of a state such as バイデン大統領 (ばいでんだいとうりょう) — President Biden.

バイデン大統領は、歴史的な演説で世界に感動を与えました。 (ばいでんだいとうりょうは、れきしてきなえんぜつでせかいにかんどうをあたえました。) — President Biden delivered an inspiring speech that moved the world.

How to Use Japanese Honorifics

As you’ve seen, most honorifics are used as suffixes—i.e., they come after the name of the person they’re being used for. Sometimes, they can stand on their own. Knowing what they are is very important to understanding Japanese culture.

If your head is already spinning from all of these honorifics, here are some general rules to follow:

Use honorifics for others, not for yourself.

I can’t stress it enough: Never use an honorific to refer to yourself. It’s considered cocky and a sign of bad manners.

Use honorifics when they’re needed.

This may seem like common sense, but when you need to use an honorific, use it. Even if you’re not sure, use it!

When referring to someone else (or even to your company), be sure to use the appropriate honorific as needed. Failing to do so might result in appearing arrogant or ill-mannered.

Use honorifics with polite speech.

Honorifics are generally tied to all the other forms of polite speech in Japanese—most notably with the – ます form.

If you’re not sure about which suffix to use, use this polite form as a buffer.

Drop honorifics when referring to family (usually).

When talking about a member of your family, you can drop the honorific. For example, you can refer to your sister without using ちゃん or your father with something as cheeky as 親父 if you’re talking among good friends.

Drop honorifics with people very close to you.

Let me clarify that. The only honorific you can drop is the one referring to the person you’re talking to—not the honorifics relating to other people not present.

For example, if you’re talking with your girlfriend, best friend or dog, feel free to drop that honorific. It shows intimacy.

Learn proper usage before dropping honorifics.

Now don’t get me wrong. It’s usually a good idea to copy native speakers to learn vocabulary, expressions and everyday idioms.

But honorifics are an exception.

Most of the younger generation of Japanese—mainly those born after 1980—often prefer to hear their names without the honorifics, giving a casual air even among people they don’t know that well.

But as a student of Japanese, you really don’t want to assume this is the case. You need to understand the proper use of honorifics before making any potentially awkward slip-ups.

It helps to listen out for them in conversations, TV shows and videos to really get to know their usage before you start dropping them. For instance, on the language learning platform FluentU, you can see these honorifics in action.

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Use this information about Japanese honorifics when you’re out in the real world. Read books, talk to people and listen to different dialects.

In other words, live the language in its purest form.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing...

If you love learning Japanese with authentic materials, then I should also tell you more about FluentU.

FluentU naturally and gradually eases you into learning Japanese language and culture. You'll learn real Japanese as it's spoken in real life.

FluentU has a broad range of contemporary videos as you'll see below:

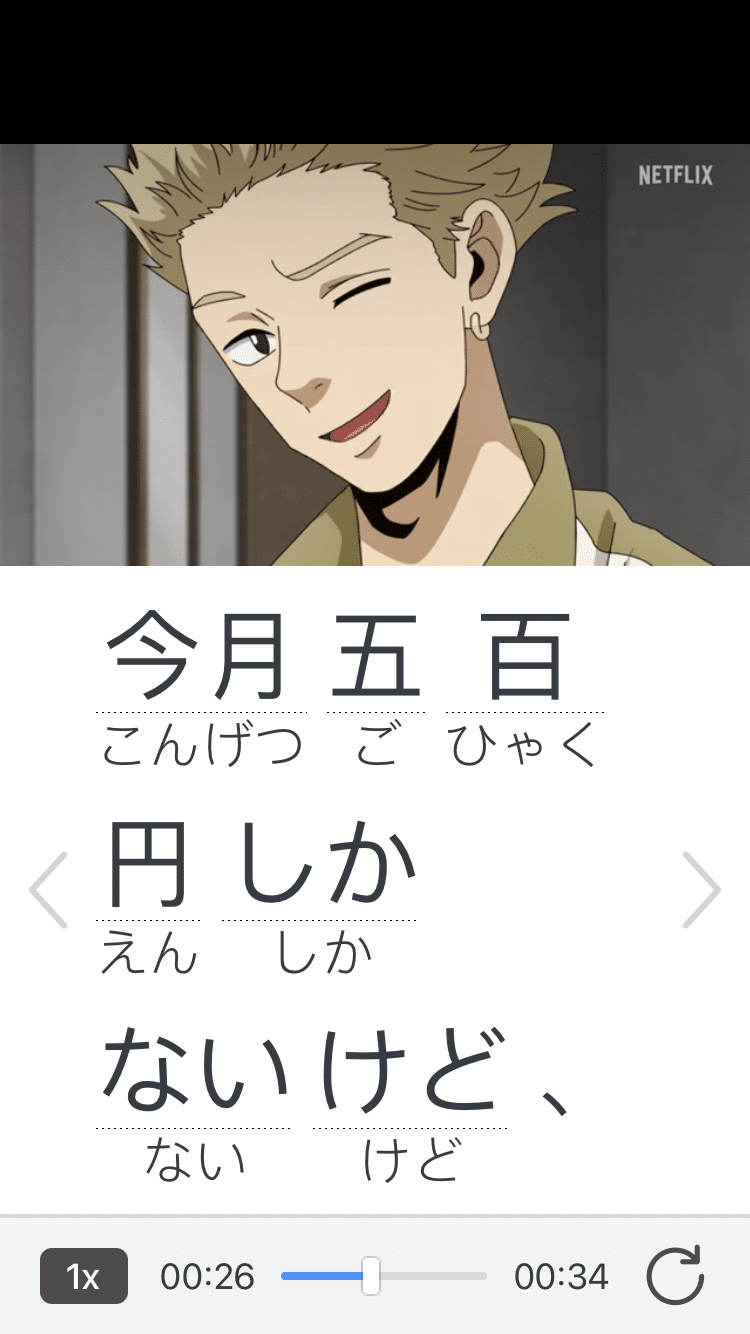

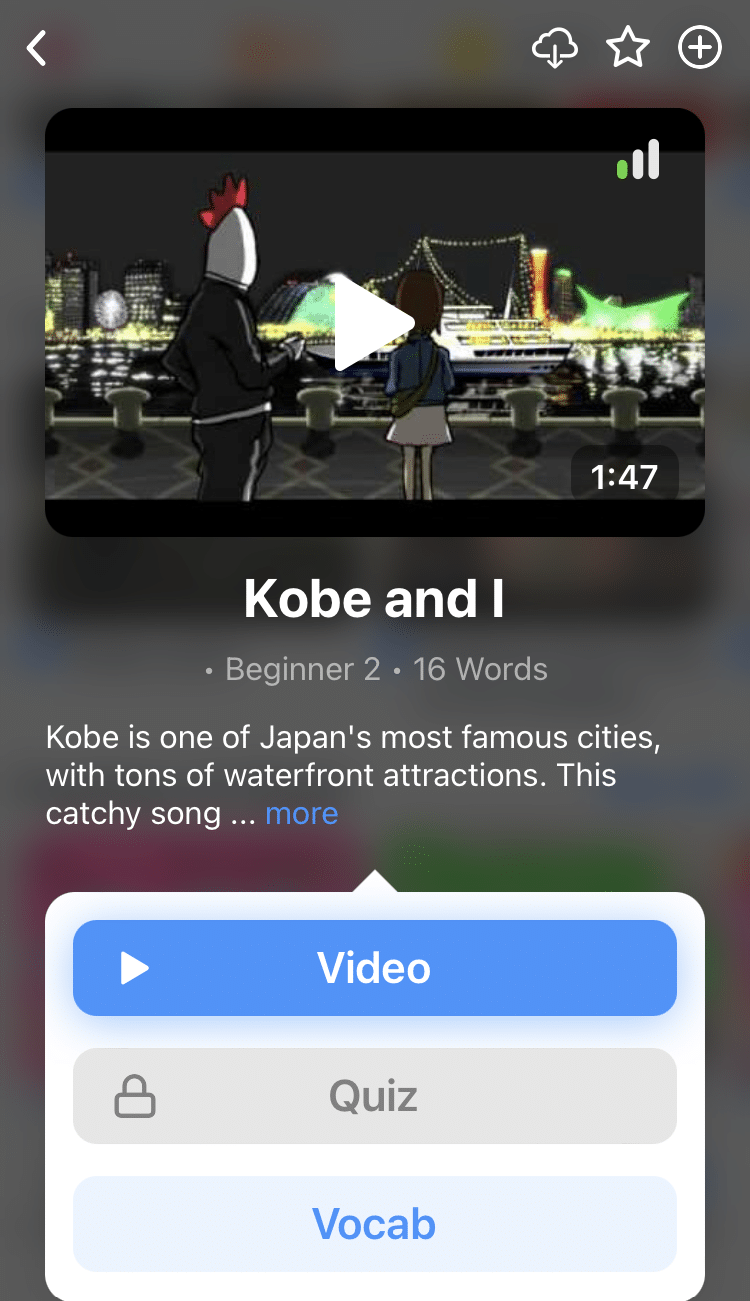

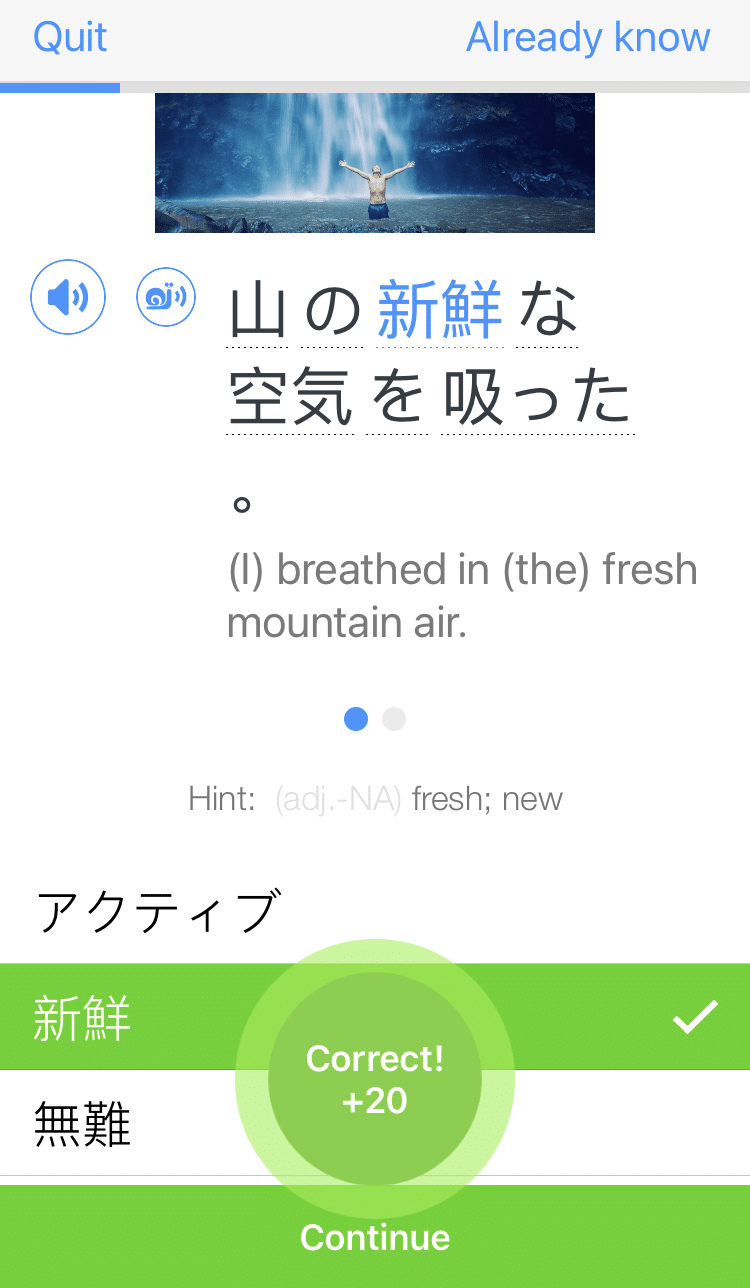

FluentU makes these native Japanese videos approachable through interactive transcripts. Tap on any word to look it up instantly.

All definitions have multiple examples, and they're written for Japanese learners like you. Tap to add words you'd like to review to a vocab list.

And FluentU has a learn mode which turns every video into a language learning lesson. You can always swipe left or right to see more examples.

The best part? FluentU keeps track of your vocabulary, and gives you extra practice with difficult words. It'll even remind you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. You'll have a 100% personalized experience.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)