7 Major Japanese Dialects You Should Know to Seem More Local

Overflowing with confidence, you roam the streets of Japan ready for your first meaningful interaction with a native speaker. You want to go to a hobby shop, so you ask a friendly-looking Japanese man walking by if he knows where one is.

“知らん” (I don’t know), he answers before vanishing into the crowd.

What did he just say?

Little did you know, you just stumbled onto a speaker of the Hakata Ben dialect of Japanese.

You see, Japanese isn’t just Standard Japanese—there are seven major dialects of the language spoken in different areas of the country.

In this post, we’ll tell you about each one of those, including examples about how they differ from standard Japanese, and we’ll also detail what a dialect is.

Contents

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Standard Japanese

The form that is considered the standard is called 標準語 (ひょうじゅんご), “Standard Japanese,” or 共通語 (きょうつうご), “common language.” As with the standardized British English of London, spoken by the high class Londoners of previous centuries, 標準語 was spoken by the high class citizens of Tokyo during the Meiji Restoration of 1868.

Today, it is the form taught in schools, used on television and in official government communication. Due to this modernization, speakers of regional dialects experienced a sense of inferiority. After World War II, the rise of the already inflated Japanese nationalism led to a push for the replacement of all regional varieties with the “common language.”

The conversion was far from successful. Yes, Standard Japanese is the primary language taught in schools and used in all official matters. However, as difficult as it was for the regional varieties to cast out this sense of inferiority, they are now considered something more valuable: a token of the past, a nostalgic memoir, a verification of local identity.

It is no longer shameful to speak in your dialect as it was in the past. Young people are even beginning to create their own Creoles—distinct regional speech forms—based on the regional dialect, like the Japanese spoken in Okinawa, for example.

Major Japanese Dialects

1. Hakata Ben

The Hakata dialect (博多弁/はかたべん) is spoken in and around Fukuoka city. It is sometimes called 福岡弁 (ふくおかべん) due to its increased popularity as the typical dialect of Fukuoka and its suburbs. Recently the dialect is being used in regional news along with Standard Japanese.

Grammar point | Standard Japanese | Hakata Ben |

だ、じゃ | 犬だね (いぬだね) It’s a dog, isn’t it? | 犬やね (いぬやね) |

生徒だけど (せいとだけど) I’m a student but… | 生徒やけど (せいとやけど) | |

赤じゃない (あかじゃない) It’s not red. | 赤やない (あかやない) | |

―ない | 食べない (たべない) I don’t eat. | 食べん (たべん) |

知らない (しらない) I don’t know. | 知らん (しらん) | |

―い | 遅い (おそい) It’s late. | 遅か (おそか) |

良い (よい) It’s good. | 良か (よか) | |

Final Particle ―よ | それだよ That’s it. | それやばい |

言ったよ (いったよ) I said it. | 言ったばい (いったばい) |

2. Osaka Ben

The Osaka dialect (大阪弁/おおさかべん), more commonly known as part of the Kansai dialects (関西弁/かんさいべん), is spoken in the Kansai region. In this area, almost everyone is speaking a dialect.

Osaka Ben is characterized as a more melodic and slightly harsher version of Standard Japanese. The thing you might first notice when you hear a person from Osaka speak is that they easily omit the particles.

Grammar point | Standard Japanese | Osaka Ben |

Final Particle ―ね | 寒いね (さむいね) It’s cold, isn’t it? | 寒いな (さむいな) |

始まるね (はじまるね) It’s starting, isn’t it? | 始まるな (はじまるな) | |

―ない | 飲まない (のまない) I don’t drink. | 飲まへん (のまへん) |

食べない (たべない) I don’t eat. | 食べへん (たべへん) | |

から | 帰るから (かえるから) I’m leaving. | 帰るさかい (かえるさかい) |

暇だから (ひまだから) I’m bored. | 暇やさかい (ひまやさかい) | |

Final Particle ―よ | 良かったよ (よかったよ) It was good. | 良かったで (よかったで) |

食べたよ (たべたよ) I ate. | 食べたわ (たべたわ) |

3. Hiroshima Ben

Back in 1974, there was a movie called “The Yakuza” (Kudos if you know it). This movie used the dialect native to the Chugoku region.

Ever since, the local dialect is commonly associated with the Japanese mafia, which is unfair, I know. Part thanks to the movie, the Hiroshima Ben (広島弁/ひろしまべん) is one of the most recognizable Japanese dialects.

Grammar point | Standard Japanese | Hiroshima Ben |

だ、 | 犬だね (いぬだね) It’s a dog, isn’t it? | 犬じゃね (いぬじゃね) |

生徒だけど (せいとだけど) I’m a student but… | 生徒じゃけど (せいとじゃけど) | |

元気だ (げんきだ) I’m fine. | 元気じゃ (げんきじゃ) | |

―ない | 食べない (たべない) I don’t eat. | たべん (たべん) |

しない I don’t do [something]. | せえへん | |

―でください | 飲まないでください (のまないでください) Please don’t drink. | 飲みんさんな (のみんさんな) |

書かないでください (かかないでください) Please don’t write. | 書きんさんな (かきんさんな) | |

―てあげる、であげる | 教えてあげる (おしえてあげる) Let me show you. | 教えちゃる (おしえちゃる) |

選んであげる (えらんであげる) Let me make a choice. | 選んじゃる (えらんじゃる) |

4. Kyoto Ben

Part of the Kansai collection of dialects (関西弁/かんさいべん), Kyoto Ben (京都弁/きょうとべん) along with the Osaka Ben (大阪弁/おおさかべん), are called the Kamigata dialect (上方言葉/かみがたことば, 上方語/かみがたご).

The Kyoto Ben, the traditional dialect of Kyoto, is known for its softness and politeness. Due to its connections with the Geisha culture, it’s sometimes considered feminine and elegant.

Kyoto Ben used to be the Standard form of the language until the Meiji Restoration. Thus, many speakers of the dialect are very proud of their distinct accent.

Grammar point | Standard Japanese | Kyoto Ben |

Final Particle ―よ | 行きますよ (いきますよ) I’m going. | 行きますえ (いきますえ) |

こちらですよ Here it is. | こちらどすえ | |

Final Particle ―ね | そうですね That’s right. | そうどすな |

暑いですね (あついですね) It’s hot, isn’t it? | 暑うおすな (あつうおすな) | |

です、でして | そうです That’s right.

| そうどす |

どうでした How was it? | どうどした | |

ありません | 地図はありません (ちずはありません) There is no map. | 地図はおへん (ちずはおへん) |

学生じゃありません (がくせいじゃありません) I’m not a student. | 学生やおへん (がくせいやおへん) |

5. Nagoya Ben

I think you’re getting the pattern of my dialect overviews. So where do you think Nagoya Ben (名古屋弁/なごやべん) is spoken? You guessed right: In Nagoya City of the Aichi prefecture.

The dialect is a mixture of both eastern and western Japanese dialects, due to the geographical position of Nagoya. Even though the accent is pretty close to standard Tokyo accent, speakers of Nagoya Ben are more than often characterized as speaking like a cat.

Grammar point | Standard Japanese | Nagoya Ben |

Final Particle ―よ | 美味しいよ (おいしいよ) It’s tasty. | 美味しいに (おいしいに) |

良かったよ (よかったよ) It was good. | 良かったに (よかったに) | |

Negative form ―ない | 飲まない (のまない) I don’t drink. | 飲ません (のません) |

食べない (たべない) I don’t eat. | 食べせん (たべせん) | |

―てください | 書いてください (かいてください) Please write. | 書いてちょう (かいてちょう) |

来てください (きてください) Please come. | 来てちょう (きてちょう) | |

―くなる | 大きくなる (おおきくなる) It becomes big. | おおきなる (おおきなる) |

安くなる (やすくなる) It becomes cheap. | 安なる(やすなる) |

6. Sendai Ben

Sendai Ben (仙台弁/せんだいべん) is part of the dialect group Tohoku Ben (東北弁/とうほくべん), spoken in Tohoku region. Sendai is the capital city of the Miyagi prefecture.

The Sendai Ben is the closest of the Tohoku ben to the standard form of Japanese. Closer to Hokkaido, the regional dialects are so different, subtitles may be needed with mainstream media.

Grammar point | Standard Japanese | Sendai Ben |

Particle ―を | 雑誌を買った (ざっしをかった) I bought a magazine. | 雑誌ば買った (ざっしばかった) |

窓を開ける (まどをあける) I open a window. | 窓ば開ける (まどばあける) | |

Particle ―に・へ | 東京へ行く (とうきょうへいく) I go to Tokyo. | 東京さ行く (とうきょうさいく) |

友達に貸した (ともだちにかした) I lent it to a friend. | 友達さ貸した (ともだちさかした) | |

だろう、でしょう | 寒いだろう (さむいだろう) It will be cold. | 寒いべ (さむいべ) |

日本人でしょう (にほんじんでしょう) He’s probably Japanese. | 日本人だべ (にほんじんだべ) | |

そう | そうだ That’s right. | んだ |

そうじゃない That’s not it. | んでね |

7. Hokkaido Ben

The island of Hokkaido was settled fairly recently compared to the rest of Japan. After the Meiji Restoration, people from the Tohoku and Hokuriku regions migrated to Hokkaido and created a unique amalgamated dialect. Thus, Hokkaido Ben (北海道弁/ほっかいどうべん) is a mixture of different varieties with a set of distinct characteristics.

Grammar point | Standard Japanese | Hokkaido Ben |

よね? / でしょう? | 行くよね (いくよね) I’m going. | 行くっしょ (いくっしょ) |

これだよね This is it, isn’t it? | これっしょ | |

―よね? / でしょう? | 言ったよね (いったよね) I said it, didn’t I? | 言ったしょや (いったしょや) |

明日でしょう (あしたでしょう) It’s probably tomorrow. | 明日しょや (あしたしょや) | |

Potential form of Godan Verbs turns into | 行ける (いける) I can go. | 行かれる (いかれる) |

飲める (のめる) I can drink. | 飲まれる (のまれる)] | |

―だろう / でしょう | 寒いだろう (さむいだろう) It will be cold. | 寒いべ (さむいべ) |

日本人でしょう (にほんじんでしょう) He’s probably Japanese. | 日本人だべ (にほんじんだべ) |

What Is a Dialect?

According to David Crystal, one of the most celebrated linguists of our time, a dialect is any variety of a language, including the standardized version. A dialect is also any language that is socially linked to a specific region, generally accepted to be derived from a national standard language.

Japan has a lot of dialects. Considering the length of time the island has been inhabited, the isolation from all external affairs until the late 19th century and the internal isolation of the numerous shogunates, the existence of so many dialects shouldn’t come as a surprise.

The main differences between the dialects are generally matters of pitch accents, use of inflections, vocabulary and the use of particles. There are instances where they differ even in how they use vowels and consonants.

There is a main distinction between the different Japanese dialects. They are divided into two major types: the Tokyo-type (東京式/とうきょうしき) and the Kyoto-Osaka type (京阪式/けいはんしき). As you can probably guess, it is a division based on the northern and the southern dialects.

There are dialects from peripheral regions that may be incomprehensible to speakers from different parts of the country. There are even mountain villages or isolated islands that speak dialects derived from Old Japanese.

But don’t worry—you don’t need to study Old Japanese. You just need to be vaguely familiar with the seven major dialects. This will give you just enough knowledge to know when you’re talking to a cheerful guy from Hokkaido or a natural born comedian from Osaka.

If you want to hear some of these dialects out in the wild, FluentU can be a helpful resource.

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

So get familiar with these dialects, try out a couple and then tell a friend when you hear a distinct one. It will definitely make you sound more local.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing...

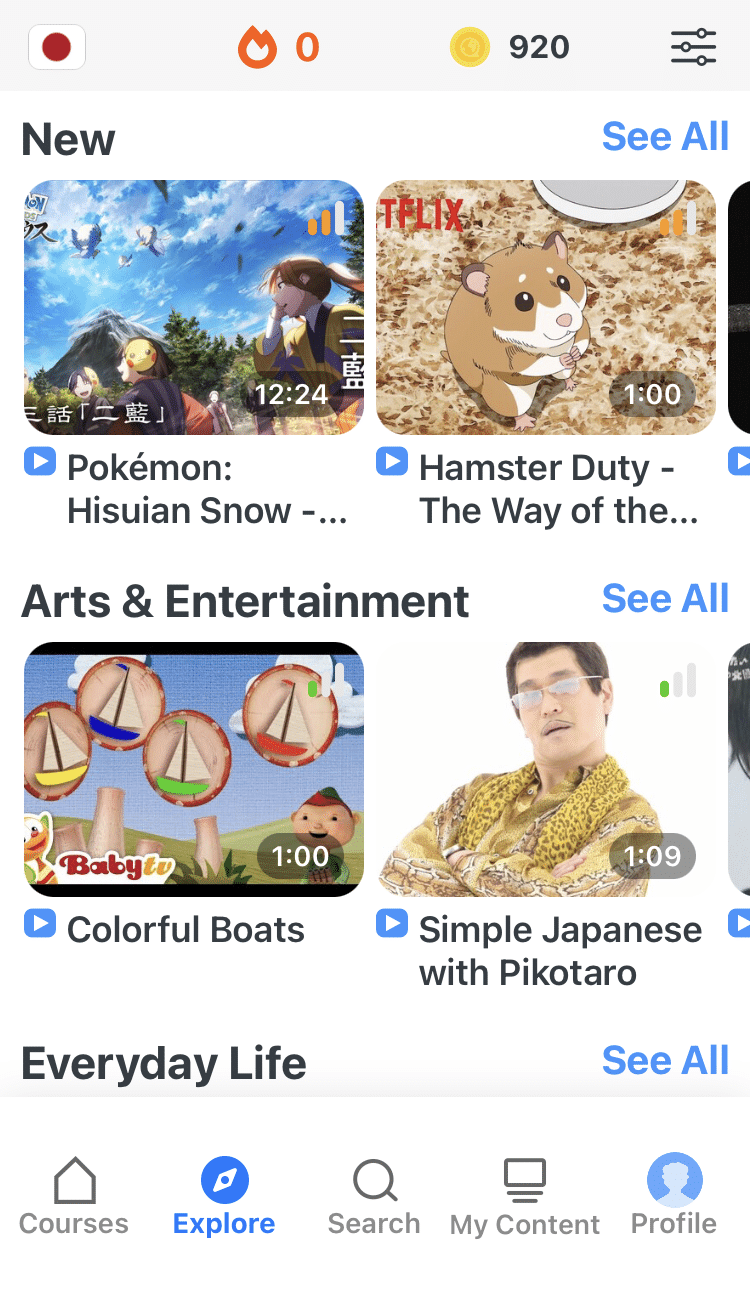

If you love learning Japanese with authentic materials, then I should also tell you more about FluentU.

FluentU naturally and gradually eases you into learning Japanese language and culture. You'll learn real Japanese as it's spoken in real life.

FluentU has a broad range of contemporary videos as you'll see below:

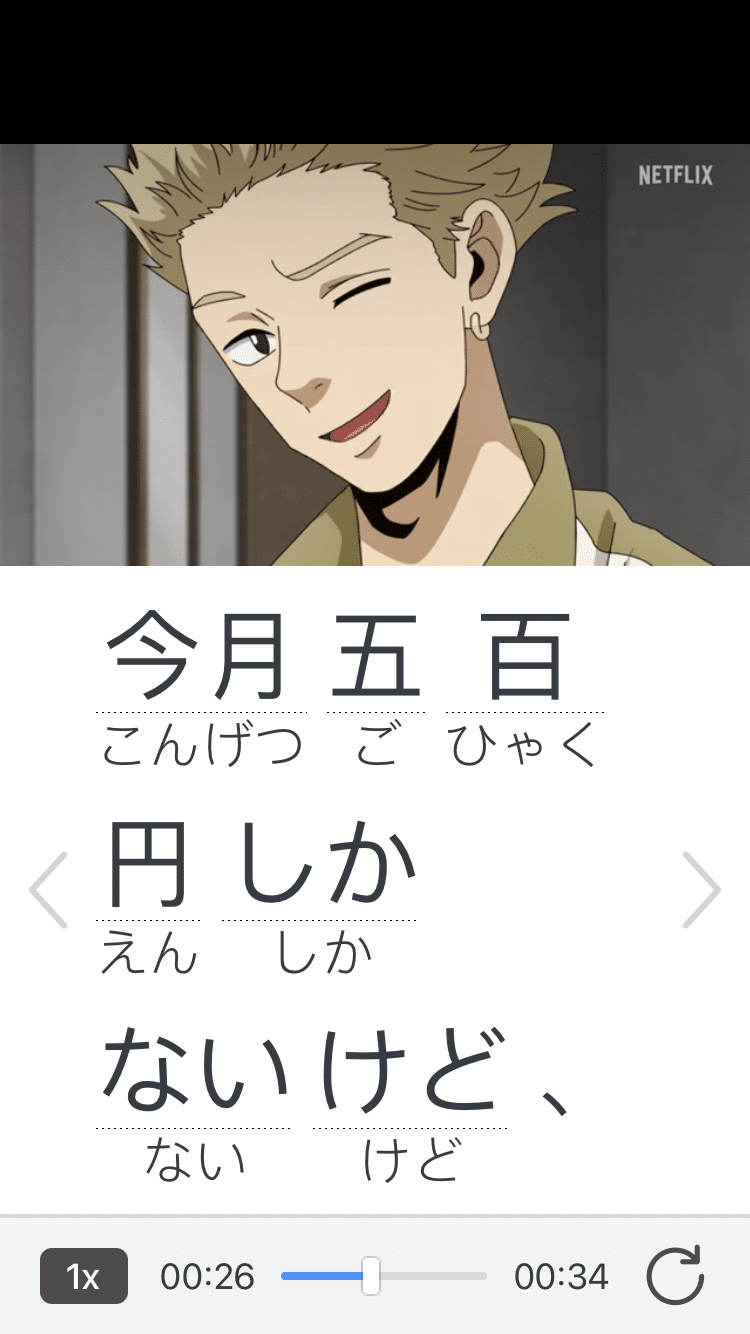

FluentU makes these native Japanese videos approachable through interactive transcripts. Tap on any word to look it up instantly.

All definitions have multiple examples, and they're written for Japanese learners like you. Tap to add words you'd like to review to a vocab list.

And FluentU has a learn mode which turns every video into a language learning lesson. You can always swipe left or right to see more examples.

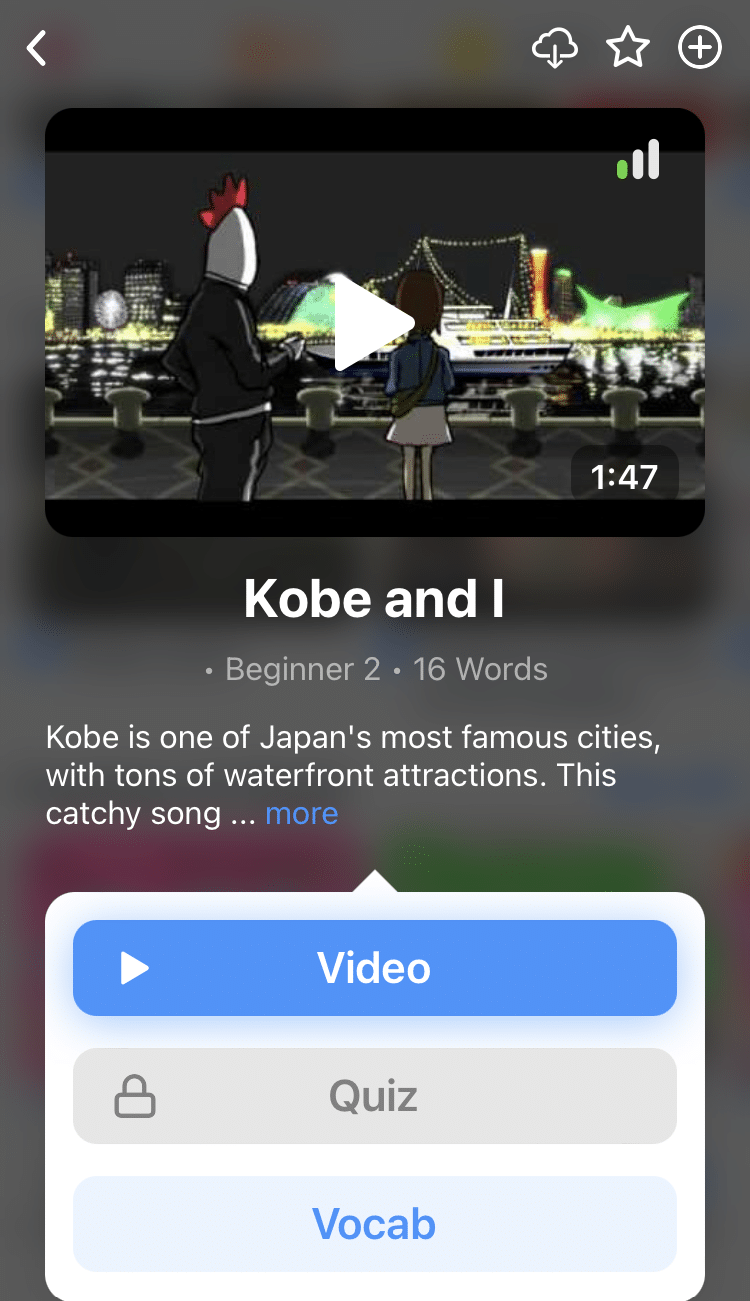

The best part? FluentU keeps track of your vocabulary, and gives you extra practice with difficult words. It'll even remind you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. You'll have a 100% personalized experience.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)