8 Cool Ways to Use Totally Informal Japanese

If you started your Japanese learning adventure in the classroom, chances are you first learned the semi-polite, neutral way of speaking.

But listening to Japanese songs, watching anime, getting hooked dorama and chatting with Japanese friends often require you to know informal Japanese.

In this post, you’ll learn eight ways to master informal, casual Japanese.

Contents

- 1. Master Casual Form in the Present Tense

- 2. Master Casual Form in the Past Tense

- 3. Use ちゃう/ちゃった and じゃう/じゃった

- 4. Use 〜って

- 5. Use なあ〜

- 6. Drop Particles

- 7. Drop い

- 8. Use Gender-specific Phrases

- When You’ll Use and Hear Informal Japanese

- And One More Thing...

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

1. Master Casual Form in the Present Tense

Most Japanese students are familiar with casual conjugation already. It’s how most dictionaries and translators write verbs and adjectives.

Whatever you call it (plain form, casual form or dictionary form) probably depends on your teacher or textbook. But for this article, I’ll call it casual form, casual speech or casual voice.

If you aren’t familiar with the casual form of verbs yet, you may need to spend some more time on this, but I’ll cover it briefly here.

First, we’ll split Japanese verbs into three groups: Group 1 verbs, Group 2 verbs and Irregular verbs.

Group 1 Verbs

Most Group 1 verbs have a -ます stem that ends with an い sound. For example:

To conjugate Group 1 verbs into casual form, drop the -ます and change the い sound to an う sound:

To turn these casual form verbs into negatives, change the う sound to an あ sound and add ない:

Please note that when the word ends with an う sound—like 会う (あう: to meet)—instead of あ, the sound changes to わ, to make it easier to pronounce. For example:

Group 2 Verbs

Group 2 verbs are simpler to conjugate for casual Japanese but can be trickier to spot.

Most have a -ます stem that ends with an え sound, but not all do.

Just be sure to check the casual form of all the new verbs you learn!

Some examples of Group 2 verbs are:

To conjugate these verbs for informal Japanese, you drop the -ます and add る:

Drop the -ますand add ない for the negative version:

Irregular Verbs

There are only two irregular verbs, and they’re both very common:

To conjugate these in the present tense with a casual voice, here’s what to do:

In the negative, you drop the -ます and add ない:

Nouns and adjectives

Nouns and adjectives conjugate just the same. (Here’s a guide if you’re unfamiliar with the process.)

The only difference in casual Japanese is that the verb that follows them (です) becomes だ.

For example:

*Please note that unless you’re using it for emphasis, だ isn’t ever necessary when following い-adjectives

Unlike です, which seems to end almost every sentence in neutral speech, だ sounds rough or masculine.

Use だ when speaking in the past tense (which I’ll explain in the next section) or if you’re going to follow it with ね or よ.

For example:

この写真は綺麗だね? (この しゃしんは きれいだね?) — Isn’t this photo beautiful?

羨ましいよ! (うらやましいよ!) — Wow, I’m so jealous!

2. Master Casual Form in the Past Tense

Group 1 Verbs

To use Group 1 verbs in casual past tense, conjugate them the same way you would into て-form—but instead of て, use た.

For example:

If you don’t know the て-form, here’s a quick explanation.

Group 2 Verbs

Take off the -ます stem (or the る) and add た.

For example:

Irregular Verbs

Irregular verbs conjugate into casual past tense the same way as Group 2 verbs. Simply remove the ます-stem and replace it with た.

Nouns and adjectives

Follow nouns or な-adjectives (the words that you would’ve followed with -でした in polite speech) with だった.

い-adjectives conjugate the same way that they do in neutral past tense. Drop the い and replace it with かった.

For example:

ない is an い-adjective, so use verbs in plain-negative past tense by ending with –なかった.

For example:

3. Use ちゃう/ちゃった and じゃう/じゃった

These sentence endings are usually more challenging since there’s no English equivalent. They also have multiple uses.

However, they’re very common among young Japanese people, so they’re worth learning. You’ll also often hear them in movies, dorama and anime.

Present tense

ちゃう and じゃう are the casual forms of てしまう (formal form: てしまいます), the verb to mean that something will happen, either “regrettably” or “with determination.”

You can use ちゃう/じゃう the same way you would てしまう: by conjugating the verb you are describing into て-form and adding ちゃう/じゃう.

So to say that you will hang out with someone you don’t really want to see, you would say:

あの人と遊んじゃう。 (あのひとと あそんじゃう) — I’ll hang out with him.

Or to say that you will finish your homework with a sense of determination, you would say:

宿題を終わらせちゃう。 (しゅくだいを おわらせちゃう) — I will finish my homework.

Past tense

The past tense meaning of this verb is completely different than in the present tense.

The past tense conjugation is てしまった (formal form: てしまいました), and it means that something did happen and that the result was less than good.

So, to end a sentence with ちゃった or じゃった indicates that the speaker is unhappy or disappointed with the result of whatever happened.

It can also indicate that something is finished. In English, we might say something is “over and done with.”

So it could indicate disappointment or relief—you can (hopefully) glean the meaning from the context.

Choosing between ちゃう/ちゃった and じゃう/じゃった

The pronunciation of this phrase depends on what consonant it follows.

Use じゃう/じゃった if the casual form of the verb stem you’re describing ends with:

- ぶ

- む

- ぬ

- ぐ

Here’s an example of how this looks:

今晩読んじゃう。 (こんばん よんじゃう。) — I am going to read tonight. (said with determination)

Use ちゃう/ちゃった following:

- Group 2 verbs

- Irregular verbs

- Any other Group 1 verb stem consonant

For example:

カキ食べちゃった... (かき たべちゃった...) — I regret eating those oysters…

明日、本当にしちゃう。 (あした、ほんとうに しちゃう) — Tomorrow, I really will do it.

急いじゃう。 (いそいじゃう) — Unfortunately, I have to hurry.

ジムに行っちゃった。 (じむに いっちゃった) — I went to the gym. (said with a sense of “got that out of the way.”)

4. Use 〜って

〜って can be used in place of the particle と before verbs like 言う (いう – to say) and 思う (おもう – to think).

For example:

メリーちゃんが寒かったって言った。 (めりーちゃんが さむかった っていった) — Mary said it was cold.

大学に行きたいって思う 。 (だいがくに いきたい っておもう) — I think I want to go to university.

You can also use 〜って to end sentences in place of the verbs そうです and と言っています to indicate that you heard something or that somebody said something.

メリーちゃんが寒かったって。 (めりーちゃんが さむかった って) — Mary said it was cold.

テストは難しいって。 (てすとは むずかしい って) — I heard that the test will be hard.

5. Use なあ〜

なあ〜 is a funny little sentence-ender that you’ll probably start to notice everywhere.

It seems to be used in just about any context, but most commonly as a slightly more pushy version of ね~. As in, “can you believe it?” or “don’t you agree?”

Women and girls should be mindful about using なあ〜 too often, as it can come across as rough or crude.

6. Drop Particles

If you’re like me and never quite got the hang of when to use を versus が, you’ll love this aspect of casual Japanese.

は, を and が can all be dropped from your sentences when speaking casually, and you’ll still make perfect sense.

Another particle that’s dropped in casual Japanese is the question particle か.

Indicate that you’re asking a question in casual Japanese the same way you do in English: with a question mark or with your intonation.

7. Drop い

When talking about doing something in the present tense in neutral Japanese, you’d use しています.

The dictionary conjugation of this would logically be している, but in conversation, it’s common to drop the い to shorten it to してる.

For example:

海に来てる。 (うみに きてる) — We are at the beach.

二人付き合ってる。 (ふたりつきあってる) — Those two are going out.

You can do this with all verbs to make them run off the tongue a little easier.

8. Use Gender-specific Phrases

Neutral Japanese is gender-neutral, but in casual Japanese, there’s a little more freedom for men and women to color and characterize how they speak.

女言葉 (おんな ことば) — “Women’s words”

While it isn’t necessary for anyone to use sentence-enders in casual Japanese, girls and women will sometimes end a sentence with わ or の, or gender-neutral ね and よ.

For example:

そのドレス高いわ! (そのどれす たかいわ) — That dress is expensive!

どこで会うの? (どこで あうの) — Where shall we meet?

There are many syllable combinations that females may use to end sentences, including:

- だね

- だよ

- なの

- のね

- わね

- わよ

- のよ

- だこと

Here are a few more important things to know about casual Japanese speech for females:

- Questions commonly end with either no sentence-ender or with の or なの

- Girls also sometimes refer to themselves as あたし rather than 私 (わたし), as it sounds a little more girlish and innocent

- Women referring to themselves as 僕 (ぼく) is becoming more common, but still sounds quite tomboyish

- Women can refer to men as あんた in a casual setting or very informally say “that person” あの人 (あのひと) or あの子 (あのこ)

- Women are starting to use 君 (きみ — you) to refer to men

- It’s more common for women to suffix others’ names with -ちゃん than men, though men can use it for women (and some men) they’re close to

男言葉 (おとこ ことば) — “Men’s words”

Masculine language is basically just gender-neutral informal Japanese, as most of the gendered idiosyncrasies were started by girls and women in the Meiji era.

Japanese men speaking casually might end sentences with だ, よ, ね, んだ, a combination of these or none at all.

ぞ, ぜ and だぜ are a little old-fashioned now, but I’ve heard them used by men to sound a bit more rough and manly.

Men might end a question simply by intonation, or they can use:

- か?

- かい?

- なのかい?

- だい?

- なんだい?

- んだい?

Among friends or loved ones, men might refer to themselves as 俺 (おれ) rather than the more boyish 僕 (ぼく) or to others as お前 (おまえ).

When You’ll Use and Hear Informal Japanese

- If you’re speaking to someone younger, you can usually choose how polite you want to be. If they’re older than you, keep it neutral.

- When the person you’re talking to uses informal Japanese. I always speak neutrally the first time I meet someone, no matter who they are. But I’m also a very friendly person, so I tend to slip into casual speech pretty quickly, at least with people my age and younger. If you’re shy or unsure, listen to the way they speak to you and copy.

- When talking by yourself or writing diaries. When I learned casual speech, my teacher had us write journal entries in Japanese because you wouldn’t write politely in your diary!

- Japanese media. Informal Japanese is commonly used in media, like anime, dramas, movies and more. You can watch tons of Japanese videos on language platforms like FluentU, which uses learning tools to show you how native speakers use casual speech in real-world contexts.

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Now that you’re aware of these turns of phrase, you’ll probably begin to notice them all over the place.

I hope as you build your confidence, you’ll begin to pepper your speech with these little mannerisms and really make spoken Japanese your own!

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing...

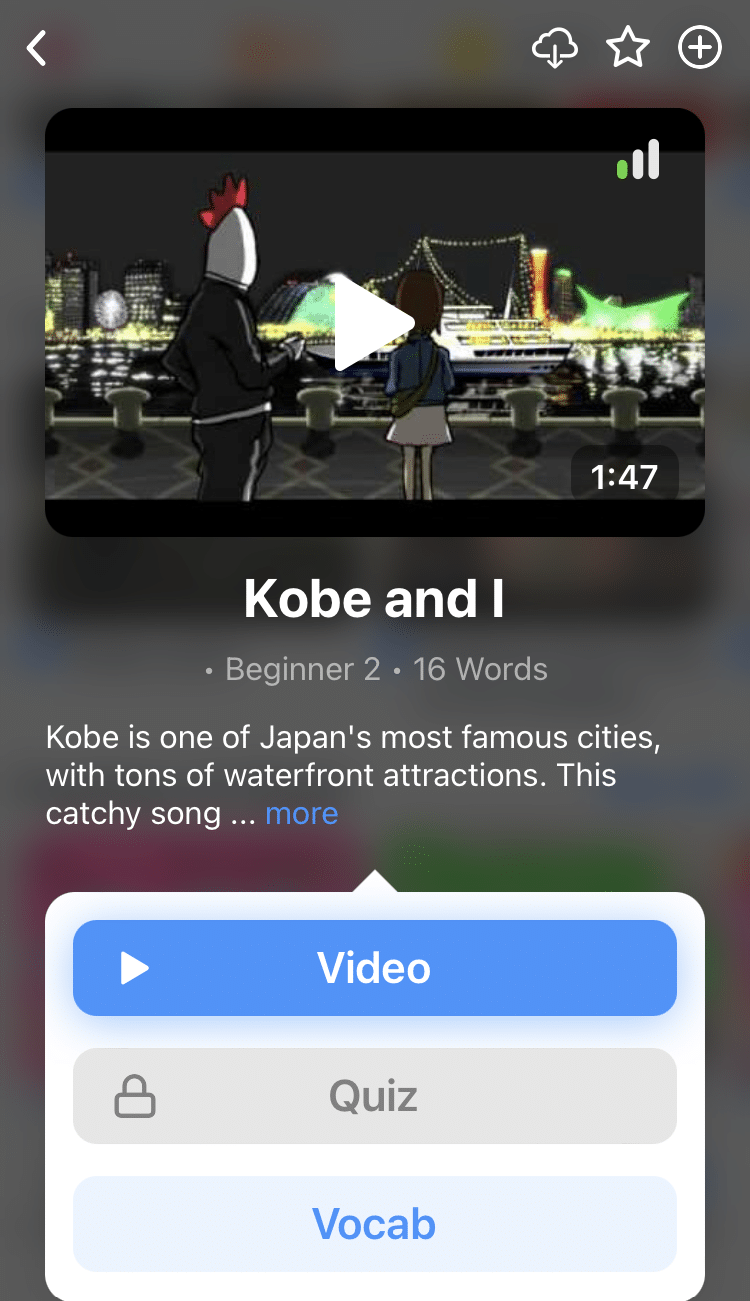

If you love learning Japanese with authentic materials, then I should also tell you more about FluentU.

FluentU naturally and gradually eases you into learning Japanese language and culture. You'll learn real Japanese as it's spoken in real life.

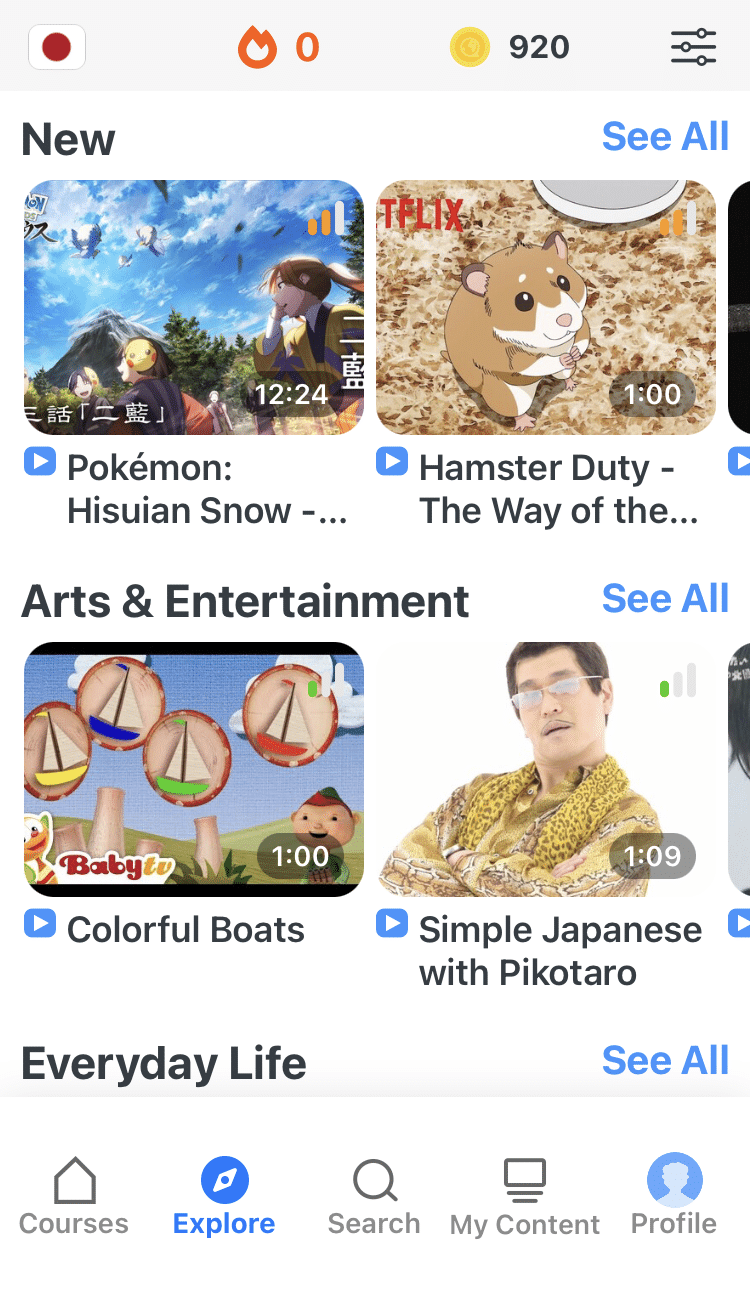

FluentU has a broad range of contemporary videos as you'll see below:

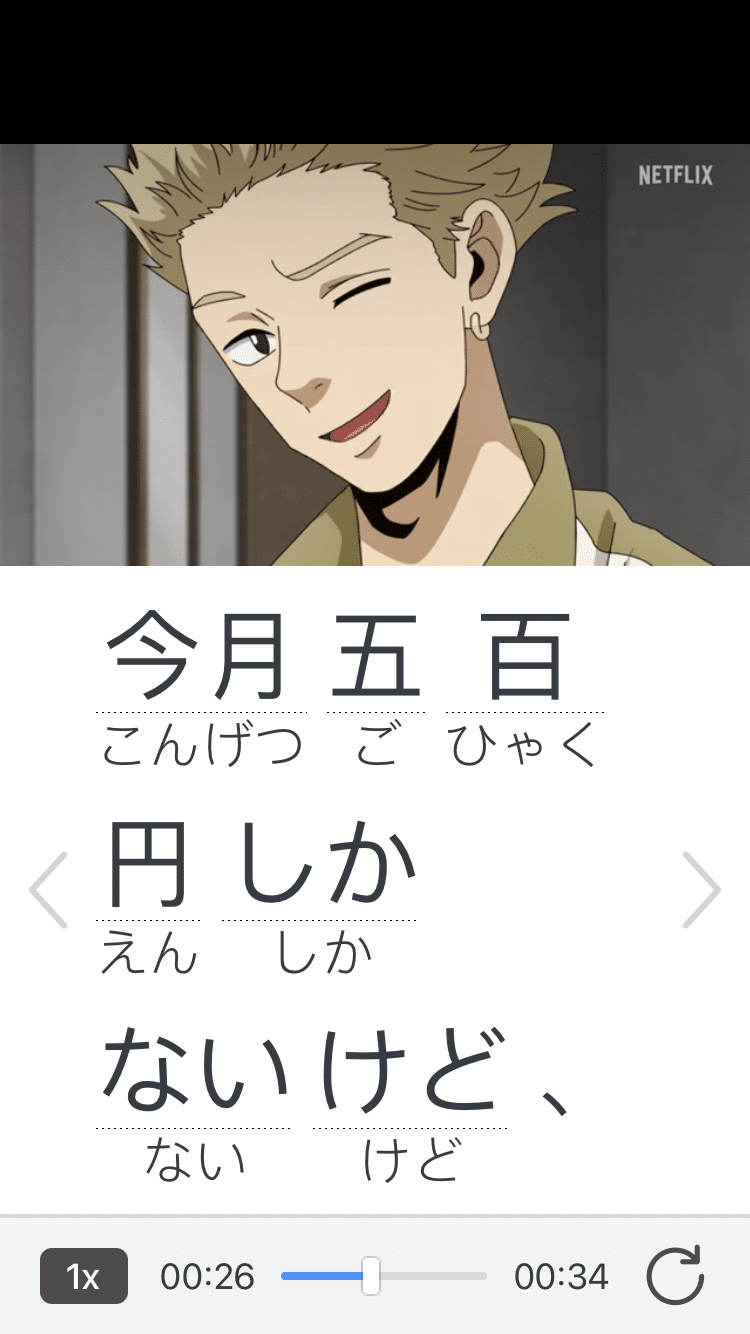

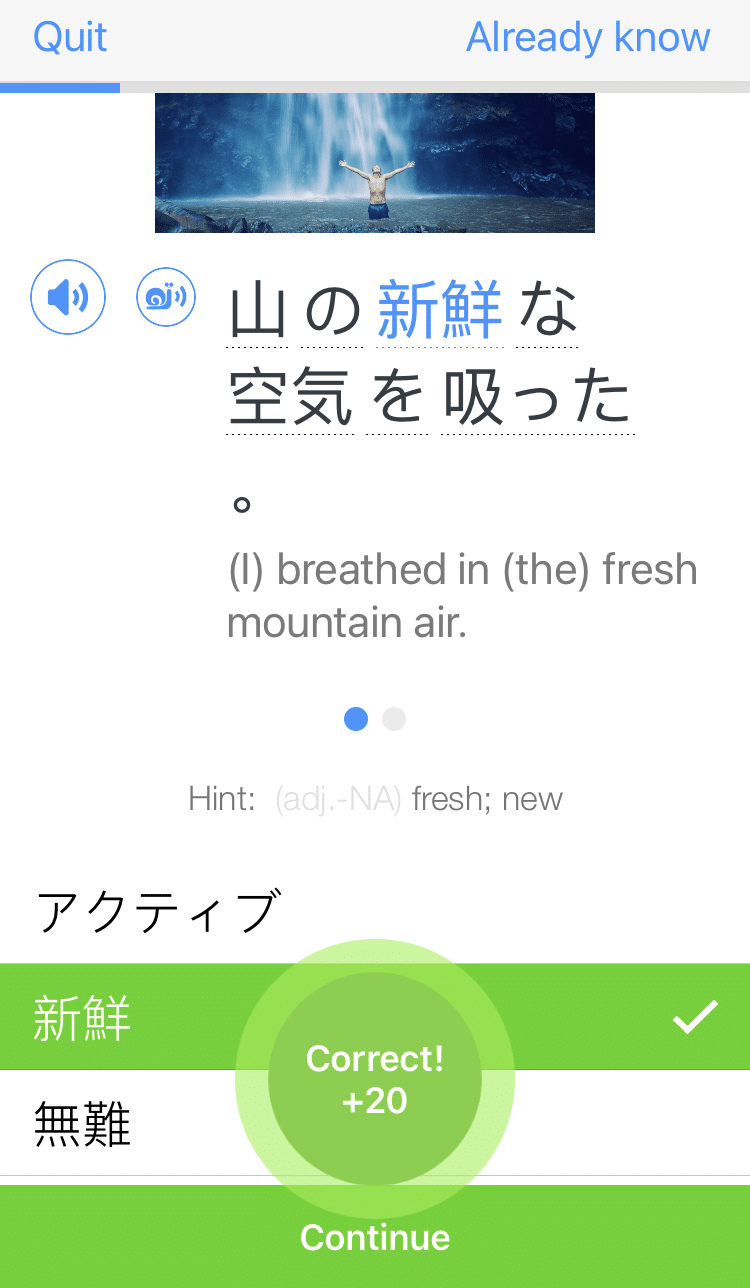

FluentU makes these native Japanese videos approachable through interactive transcripts. Tap on any word to look it up instantly.

All definitions have multiple examples, and they're written for Japanese learners like you. Tap to add words you'd like to review to a vocab list.

And FluentU has a learn mode which turns every video into a language learning lesson. You can always swipe left or right to see more examples.

The best part? FluentU keeps track of your vocabulary, and gives you extra practice with difficult words. It'll even remind you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. You'll have a 100% personalized experience.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)