German Grammar

Need the lowdown on German grammar without being overwhelmed by all the details?

You’ve come to the right place!

This guide will walk you through all the most important German grammar topics—no fuss, no muss.

You’ll also get links to our more in-depth blog posts on each topic, so you can choose to dive deeper into anything you need to learn more about right now.

Contents

- 1. Nouns

- 2. Cases

- 3. Verbs

- 4. Tenses

- 5. Adjectives

- 6. Adverbs

- 7. Conjunctions

- 8. Prepositions

- 9. Moods

- 10. Word Order

- And One More Thing...

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

1. Nouns

Nouns are the stuff of sentences, literally.

When you’re learning German nouns, you’re not just memorizing singular words. Every noun in German should be considered a two-part package—i.e., they consist of the noun itself and the article that comes with it.

200+ Common German Nouns [with Audio] | FluentU German Blog

German nouns are an essential component of any language learner’s vocabulary. Check out our list of over 200 common nouns, organized by category such as family, food,…

Capitalization

All German nouns are capitalized. You don’t really have to worry about “proper nouns” and such, unlike in English. Whether you’re referring to something with a name (“Johann Schmidt,” “Volkswagen,” “Cuddles”) or a generic person/object (“man,” “car,” “cat”), the noun would be capitalized.

8 German Capitalization Rules | FluentU German Blog

Learn all about German capitalization rules to boost your German writing skills. See how (and why) to capitalize German nouns to the nuances of formal and informal…

Gendered Articles

Articles are the little words that come before nouns. They tell you if you’re talking about something definite (the dog) or something indefinite (a dog).

There are three genders in German articles: masculine, feminine and neuter. Each has its own unique articles.

| German Article Genders | Definite Article | Indefinite Article |

|---|---|---|

| masculine | der | ein |

| feminine | die | eine |

| neuter | das | ein |

Every German noun is assigned a gender. For example, since “chair” in German is masculine, you say der Stuhl (the chair) or ein Stuhl (a chair). Similarly, with the feminine word “flower”, you say die Blume (the flower) or eine Blume (a flower).

Here are the general rules for using each article—that is, what gender you should use for which noun ending.

| Noun Ending | Article Gender |

|---|---|

| -ig, -ling, -or, -smus | masculine |

| -ei, -heit, -ik, -keit, -schaft, tät, -tion, -ung | feminine |

| -chen, -lein, -ma, -ment, -tum, -um | neuter |

Note that the articles may also change depending on which case you use.

The Ultimate Guide to Der, Die and Das | FluentU German Blog

“Der,” “die” and “das” can confuse any language learner, but with some helpful tricks you can master these German articles for “the.” Click here to learn how to nail them…

Pluralization

All plural nouns in German take on the feminine article die . They may also change their endings (most commonly –e, –er, –en or –s) depending on the root noun’s ending, gender, number of syllables and whether they’re family names.

Sometimes, an umlaut (two dots above a letter) may also be added to a vowel, like in der Koch (the chef) → die Köche (the chefs).

Plural Nouns in German | FluentU German Blog

Forming German plurals is a little complex! This post goes over the five ways to form plurals in German. You’ll learn that most nouns need an -e ending for their plural…

Compound Nouns

There are instances in German where two nouns can get squished together, creating compound nouns. These can result in combos like die Handschuhe (gloves, literally “hand shoes”) or die Arbeiterunfallversicherungsgesetz (law relating to worker’s compensation insurance).

4 Quick Tips for German Compound Nouns | FluentU German Blog

Learning German grammar? Use these quick tips to navigate the challenges of German compound nouns!

2. Cases

In German grammar, nouns and pronouns can change depending on what role they play in a sentence. This role is known as the “case.”

For example, in the sentence Ich habe einen Hund (I have a dog), “I” is the subject (the doer of the verb), so it’s in the “nominative” case. Meanwhile, “dog” is the object of the verb, meaning it’s receiving the action of the verb “have,” so it goes in the “accusative” case.

German Pronouns: Complete Guide to the 8 Different Types and How to Use Them Right | FluentU German Blog

Learn German pronouns with this comprehensive guide to the eight different types of German pronouns, when to use them and examples of them being used correctly. German…

There are four German cases to learn, and each one can change the personal pronouns and articles (both definite and indefinite) used.

Nominative

The nominative case ( der Nominativ ) is used to indicate the subject of a sentence, or the one performing the action of the verb.

In this case, you’ll be using the standard personal pronouns and articles.

| Nominative Pronouns | Nominative Articles |

|---|---|

| ich : I du : you (singular, informal) er : he sie : she es : it wir : we ihr : you (plural, informal) sie : they Sie : you (formal) | der / ein : masculine die / eine : feminine das / ein : neuter die : plural |

Accusative

The accusative case ( der Akkusativ ) is used to express the direct object of the sentence. It’s the “receiver” of the subject’s actions and is influenced by them.

Note that in accusative articles, only the masculine articles change.

| Accusative Pronouns | Accusative Articles |

|---|---|

| mich :me dich : you (singular, informal) ihn : him sie : her es : it uns : us euch : you (plural, informal) sie : them Sie : you (formal) | den / einen : masculine die / eine : feminine das / ein : neuter die : plural |

Nominative vs Accusative German Cases | FluentU German Blog

Confused about the nominative vs accusative German cases? Read this guide to learn about what the difference is, and when you should use each case. You’ll also learn which…

Dative

The dative case ( der Dativ ) is used to express the indirect object of the sentence. This would be the noun that receives or is acted upon by the direct object.

For example, in Die Junge gibt dem Hund den Ball (The boy gives the dog the ball), the dog is the indirect object (indicated by the dative dem article), since the direct object, the ball (indicated by the accusative den article), is being given to the dog.

| Dative Pronouns | Dative Articles |

|---|---|

| mir : me dir : you (singular, informal) ihm : him ihr : her ihm : it uns : us euch : you (plural, informal) ihnen : them Ihnen : you (formal) | dem / einem : masculine der / einer : feminine dem / einem : neuter den : plural |

The German Dative Case | FluentU German Blog

The German dative case is one that can be challenging for German learners. We’re here to help! This quick-and-easy guide will help you understand the dative definite…

The dative case is known to be a tricky one for German learners. It changes pronouns and articles in a way that can make discerning genders confusing. But once you’ve learned these changes, you can convey concise yet intricately complex meanings!

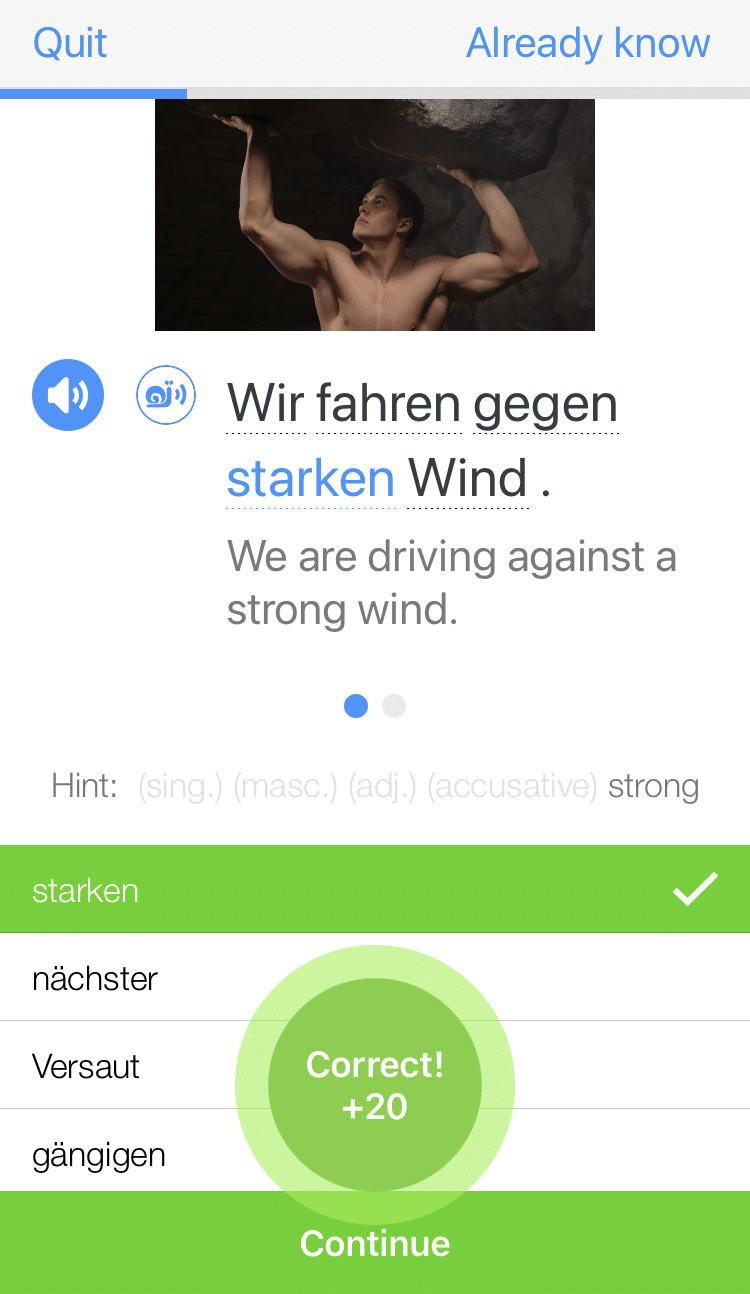

Since it can take a while to get the hang of grammatical cases in German, you can internalize them better by watching native content with targeted exercises on the language learning platform FluentU.

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Genitive

The genitive case ( der Genitiv ) is used to express possession or association. In English, we indicate possession by saying something is “of” someone or by adding -‘s to nouns. In German, the approach is a bit similar.

Typically, you’ll have to change the “possessor” noun’s article. Then, for masculine and neuter nouns, you must add –es (for short, one-syllable nouns) or –s (for multi-syllable nouns).

The genitive possessive articles depend on the gender of the possessor noun as well. For example:

Das Haus meiner Schwester ist sehr groß.

My sister’s house is very big.

| Genitive Possessive Articles | Genitive Articles |

|---|---|

| meiner : of me deiner : of you (singular, informal) seiner : of him ihrer : of her seiner : of it unser : of us eurer : of you (plural, informal) ihrer : of them Ihrer : of you (formal) | des / eines : masculine der / einer : feminine des / eines : neuter der : plural |

The Genitive Case in German | FluentU German Blog

The genitive case in German is used to express possession and other relationships between people and things, as well as periods of indefinite time. Some verbs and…

3. Verbs

Verbs are so-called “doing” or “action” words. “To play,” “to run,” “to paint” and “to learn” are all examples of verbs.

Placement

In basic German sentences, verbs will typically be in the “second position.” That is, the main conjugated verb would usually be the second word in the sentence, directly following the subject noun.

In most cases, verbs will stick to the second position even if the subject doesn’t take the first position.

For interrogative or “question” statements and imperatives, or command statements, conjugated verbs take the first position. When this happens, the German sentence takes on an “inverted word order,” and the subject comes after the verb.

Conjugation

German verbs change depending on who is doing the action, just as in English. Think of “I play” vs. “She plays.”

The only difference in German is that each “person” has a different verb ending, whether it’s “I,” “you,” “he/she/it,” “we,” etc.

This change is called conjugation. And the conjugation of verbs depends on what category they fall into.

Weak (Regular) Verbs

Most German verbs fall under this category and simply follow the normal conjugation rules.

For example, let’s see how the German weak verb spielen (to play) would be conjugated:

| German Conjugations for "Spielen" (To Play) | English Translation |

|---|---|

| Ich spiele | I play |

| Du spielst | You play (informal, singular) |

| Er spielt Sie spielt Es spielt | He plays She plays It plays |

| Wir spielen | We play |

| Ihr spielt | You play (informal, plural) |

| Sie spielen sie spielen | You play (formal) They play |

See how the stem of spiel– still sticks around? It’s just attached to different endings, namely –e, -st, -t and -en.

How to Conjugate Strong and Weak German Verbs | FluentU German Blog

German verbs are classified as weak, strong, or a mix of both. In order to use them, it’s important to know what makes them unique and what conjugation patterns they…

Strong (Irregular) Verbs

You can think of German strong verbs as “rebellious” verbs, in the sense that, during conjugations, the vowels in the stem often change in the du (you) and er / sie / es (he/she/it) forms.

For example, the German irregular verb sehen (to see) sees a vowel change from e to ie.

| Conjugations of the Strong Verb "Sehen" (To See) | English Translation |

|---|---|

| Ich sehe | I see |

| Du siehst | You see |

| Er sieht | He sees |

But if most German verbs are “weak,” how do you identify the ones that are strong? Well, we have a few tips in the article below:

40 Key Strong German Verbs | FluentU German Blog

Master strong German verbs with this straightforward guide. We’ve got a list of 40 essential strong verbs to learn, plus handy practice resources.

Mixed Verbs

True to their name, mixed verbs take on traits of both strong and weak verbs. They take on endings when conjugated to different tenses, but may also experience stem-vowel changes in the past tense.

For example, the German mixed verb kennen (to know) would become:

| Conjugations of the Mixed Verb "Kennen" (To Know) | English Translation |

|---|---|

| Ich kenne | I know |

| Ich kannte | I knew |

| Ich habe gekannt | I have known |

Separable Verbs

Separable German verbs come with prefixes that can be, well, separated. These prefixes are extra words (typically prepositions) that give total clarity to what the verb means.

The concept exists in English, too. Think about verb phrases like “getting up” or “breaking down.”

When using these verbs, the prefix is typically moved to the end of the sentence.

aufstehen (auf + stehen) — to get up, stand up

Er steht um 8 Uhr auf.

He gets up at 8 o’clock.

But beware! Not all verbs that look like they have a separable prefix actually have one, like entspannen (to relax). It might seem like you can separate ent- from -spannen, but that’s actually not the case. In fact, if you’re seeing a verb with the prefixes be-, ge-, emp-, ent-, er-, miss-, ver- and zer-, then it is not a separable verb.

Reflexive Verbs

German reflexive verbs relate to actions that would be done on the subject itself. They usually come attached with reflexive pronouns.

The verb word itself still follows their strong, weak or mixed natures, but the reflexive pronoun must show up somewhere in the sentence.

sich duschen — to shower

Ich dusche mich jeden Tag.

I shower every day.

German Reflexive Verbs: Types, Conjugation and Grammar Essentials

German reflexive verbs consist of an infinitive followed by a reflexive pronoun, and they can take the accusative or dative form. This guide will show you how to use…

Auxiliary Verbs

This small category includes verbs that often take on a “helping” role in sentences. They give more meaning and detail about another verb in the sentence.

The three main German auxiliary verbs are haben (to have), sein (to be) and werden (to become).

The auxiliary verb is generally considered the “main” verb of the sentence that’s conjugated. If it comes with a secondary verb (e.g., “have eaten”), that secondary verb may or may not be conjugated.

For example:

| German Auxiliary Verbs | Example Sentence | English Translation |

|---|---|---|

| haben (to have) | Ich habe das Buch gelesen. | I have read the book. |

| sein (to be) | Ich bin nach Berlin gereist. | I have traveled to Berlin. |

| werden (to become) | Er wird ein neues Auto kaufen. | He will buy a new car. |

A Guide to German Auxiliary Verbs | FluentU German Blog

German auxiliary verbs can be confusing but we’re here to help. Here’s a quick, fun guide to the German auxiliary verbs so you know when to use them and how to conjugate…

Modal Verbs

Modal verbs are used when you’re describing the possibility, necessity or desire of something. They’re usually meant to emphasize another verb or verb phrase. Therefore, modal verbs are technically auxiliary verbs.

In German, there are six modal verbs:

| German Modal Verbs | English Translation |

|---|---|

| dürfen | may |

| können | can |

| wollen | want |

| sollen | supposed to/expected to |

| müssen | must |

| mögen | like |

They each follow their own quirky conjugation patterns, so they don’t really fit into any of the above categories. You’ll have to memorize each of their unique conjugations.

6 German Modal Verbs and How to Use Them | FluentU German Blog

German modal verbs let you describe what you like, express a desire or even ask to go to the bathroom. Check out our post on the six modal verbs in German: dürfen (may),…

The key thing to know with modal verbs is that they send the second verb to the end of the sentence in the infinitive (how you find verbs in the dictionary). For example:

Die Kinder wollen mit dem Hund spielen.

The children want to play with the dog.

4. Tenses

Just like English, German conjugates verbs according to the time the actions indicated by these verbs took place, are taking place or will take place. These are known as tenses.

Present

While the English language has multiple ways of expressing the present tense ( das Präsens ), German only has one (whew).

Here are the general rules when conjugating German verbs in the present tense:

- For weak or regular verbs, you take the verb stem (by dropping the infinitive –en or –n ending), and add the endings unique to each personal pronoun.

- For strong (irregular) verbs, you do a similar ending switch to the verb endings. However, some strong verbs with vowels in their stems also experience vowel-changes in their du and er / sie / es conjugations.

- Mixed verbs, which include modal verbs, take on conjugations similar to both weak and strong verbs.

- Some verbs, such as sein and haben , have their own unique conjugations that you’ll just need to learn.

How to Conjugate German Verbs in the Present Tense | FluentU German

German present tense is an important topic for beginners who are learning to construct basic German sentences. Here we’ll teach you how to conjugate German verbs of all…

Past

There are two forms of the past tense in German: the simple past (a.k.a. preterite or imperfect) and the present perfect (a.k.a. perfect).

Simple Past

Like in English, the simple past tense ( das Präteritum / das Imperfekt ) conjugates verbs to a form that, by itself, will make it clear that you’re talking about actions in the past. Think about sentences like “I bought milk” or “I ran a mile.”

Here are a few examples:

| Type of Verb | Example Verb | Example Simple Past Sentence | English Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| weak verb | spielen (to play) | Ich spielte im Park. | I played in the park. |

| strong verb | fahren (to drive) | Wir fuhren nach Hause. | We drove home. |

| mixed verb | bringen (to bring) | Mutti brachte Snacks. | Mom brought snacks. |

It’s important to note that the simple past sounds a bit more literary, and therefore tends to be reserved for written or formal texts. When just talking casually, you’re more likely to use the present perfect.

German Simple Past Tense | FluentU German Blog

The German simple past tense can be confounding for language learners, especially since it’s more likely to appear in written German than in everyday speech. Still,…

Present Perfect

The present perfect ( das Perfekt ) also describes the past, but it’s probably the one you’ll encounter the most in actual conversation. For this tense, there are two elements.

Firstly, you need an auxiliary verb: haben (to have) or the verb sein (to be), the latter usually reserved for action verbs requiring movement.

The second part is the conjugated past participle of the main verb, which will have the prefix ge-, and usually a -t ending.

So, the complete formula is:

haben/sein (present tense) + main verb (past participle)

Let’s see how this works, using the same verbs and sentence format as in the simple past examples above:

| Type of Verb | Example Verb | Example Present Perfect Sentence | English Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| weak verb | spielen (to play) | Ich habe im Park gespielt. | I played in the park. |

| strong verb | fahren (to drive) | Wir sind nach Hause gefahren. | We drove home. |

| mixed verb | bringen (to bring) | Mutti hat Snacks gebracht. | Mom brought snacks. |

Notice how in the last sentence, the auxiliary verb used is sein (to be), as the sentence is about movement.

German Present Perfect Tense | FluentU German Blog

Conjugating the German present perfect tense doesn’t have to be painful! You only have to follow a handful of tips to master this tricky tense. Read on to know what those…

Past Perfect

Past perfect ( das Plusquamperfekt ) is used for actions that occurred before a specific moment in the past.

In English, the past perfect tense is created by combining the past tense of the verb “to have” and the past participle of the main verb. This creates sentences like “I had eaten” or “They had walked.”

The German past perfect is the same. You’ll now be conjugating the auxiliary verbs haben or sein into their simple past (preterite) tense.

The formula is:

haben/sein (preterite) + main verb (past participle)

For example:

| Example Verb | Example Past Perfect Sentence | English Translation |

|---|---|---|

| spielen (to play) | Ich hatte gespielt. | I had played. |

| fahren (to drive) | Mutti war gefahren. | Mom had driven. |

Future

In everyday conversation, you often just use the standard present tense alongside a word like “tomorrow” or “next week” to refer to future plans.

For example:

Morgen gehen wir ins Schwimmbad.

Tomorrow, we’re going to go the swimming pool.

However, when making promises, assumptions or formal declarations about future intent, you should use the Future 1 tense.

Future 1

Future 1 ( futur 1 ) acts much like the English simple future tense.

In the German Future 1 tense, you use the present tense of the verb werden (to become). You could think of werden as the equivalent of the English verb “will.”

The formula is then:

werden (present tense) + main verb (infinitive)

For example:

| Examples of Future 1 | English Translation |

|---|---|

| Ich werde spielen. | I will play. |

| Du wirst spielen. | You will play. |

Future 2

Future 2 ( futur 2 ) refers to actions that will be completed at some point in the future. It’s similar to the English future perfect tense—i.e., “will have” sentences.

Future 2 incorporates three verbs: werden , the main verb and either haben / sein . It’s very similar to Future 1, except the past participle of the main verb is used.

The formula is:

werden (present tense) + main verb (past participle) + haben/sein (infinitive)

| Examples of Future 2 | English Translation |

|---|---|

| Ich werde gespielt haben. | I will have played. |

| Mutti wird nach Hause gefahren sein. | Mom will have driven home. |

German Future Tense | FluentU German Blog

Check out the complete German future tense guide to using the future intent and future perfect tenses to learn how to express future actions and events in German. You’ll…

5. Adjectives

Endings

Yes, even German adjectives get endings! They’re present when the adjective comes before the noun, and this scenario can be categorized into what’s known as declension.

Weak Declension

A weak declension is when the adjective comes after a definite article (i.e., der , die , das ). In the nominative case, the adjective’s ending would be –e (for singular nouns) or –en (for plural nouns).

| Examples of Weak Declension (Adjectives) | English Translation |

|---|---|

| Der gute Mann | The good man |

| Die gute Frau | The good woman |

| Das gute Kind | The good child |

| Die guten Menschen | The good people |

Strong Declension

A strong declension is when there isn’t a definite article. Since there’s no article telling you the noun’s gender, the adjective has to pick up the slack. The adjective’s ending will usually resemble the ending of the definite article, if it had been present.

| Examples of Strong Declension (Adjectives) | English Translation |

|---|---|

| Guter Mann | Good man |

| Gute Frau | Good woman |

| Gutes Kind | Good child |

| Gute Menschen | Good people |

Mixed Declension

A mixed declension is when the adjective follows an indefinite article ( ein / eine ) or a possessive pronoun. The mixed declension adjective endings are similar to the weak declension’s, but the masculine and neuter adjective endings resemble the strong declension’s.

To make things more deliciously complex, the ending of the adjective will also depend on the noun’s case.

| Examples of Mixed Declension (Adjectives) | English Transation | Case |

|---|---|---|

| Ein alter Mann | An old man | nominative |

| Eines alten Mannes | Of an old man | genitive |

| Einem alten Mann | To an old man | dative |

| Einen alten Mann | An old man | accusative |

Want to keep these endings straight? There’s actually a two-step method to do so:

https://www.fluentu.com/blog/german/german-adjective-endings-practice/

Placement

In terms of placement, German adjectives are quite like English ones. You can place them right before the noun, or have them come after “is” or “are.”

| Examples of Adjective Placements | English Translation |

|---|---|

| Der Hund ist braun. | The dog is brown. |

| Der braune Hund isst Frühstück. | The brown dog eats breakfast. |

Comparative and Superlative

The comparative is used when you’re comparing two or more nouns, or noticing a change in how much a noun embodies an quality. In English, if something is more or less of a certain quality, you’d add –er to the end of an adjective.

Luckily, German adjectives follow a similar principle! However, if the adjective comes after an article and before a noun, you’ll need to add the correct gender- and case-specific suffix after –er.

Let’s see a couple of examples with the adjective traurig , meaning “sad”:

| Examples of Comparative Adjectives | English Translation |

|---|---|

| Er ist trauriger als er. | He is sadder than him. |

| Der traurigere Junge weinte. | The sadder boy cried. |

On the other hand, the superlative is used when a noun embodies the most of a certain quality. In English, we would add the endings -st or -est to the end of an adjective.

In German, you’d typically add two things: the ending –sten to the adjective, and the word am before the adjective. However, if the adjective comes after an article and before a noun, you won’t need am.

Again, the adjective gets an ending depending on the case and gender of the noun.

| Examples of Superlative Adjectives | English Translation |

|---|---|

| Er ist am traurigsten. | He is the saddest. |

| Der traurigste Junge weinte. | The saddest boy cried. |

For more on German comparative and superlative adjectives, check out this guide:

The German Comparative and Superlative | FluentU German Blog

The German comparative and superlative might sound tricky at first, but we’re here to help. In this guide, we show you the basic formula for German comparatives and…

6. Adverbs

Adverbs describe and add life to adjectives, verbs and other adverbs. In English, we tend to identify them through specific endings, such as -ly or -ish.

In German, there isn’t really a specific “adverb” ending. In fact, many German adjectives can take on adverbial roles without the need to add specific suffixes. For example, notice how the adjective schnell here doesn’t need to change at all to become an adverb:

Ich laufe schnell.

I run quickly.

There are also adverbial phrases that don’t necessarily contain adjectives, but are a collection of words that describe how, where or when something is being done: interessanterweise (interestingly), überall (everywhere), immer (always).

Placement

German adverbs are typically found after and close to the verbs they modify. They can be a little distanced from the verb by object nouns.

However, you can have adverbs start sentences as well. Remember the “inverted” German sentences, in which the subject isn’t the first word in the sentence but the main verb still takes the second position.

Here are some examples, each showcasing a specific adverb in different positions:

| Examples of Adverb Placements | English Translation |

|---|---|

| Ich laufe schnell. | I run fast. |

| Schnell laufe ich zur Schule. | I run quickly to the school. |

Notice again that there’s no ending for the adverb schnell.

Multiple Adverbs

When you start having more than one adverb in a sentence, then it’s time to start following a specific order: time, manner, place.

In other words, adverbs describing “when” come first, followed by those describing “how” and then finishing with those describing “where.”

For example:

Gestern habe ich viel in der Bibliothek gelesen.

I read a lot in the library yesterday.

Gestern means “yesterday” (adverb of time), viel means “a lot” (adverb of manner), and in der Bibliothek means “in the library” (adverb of place).

The Complete Guide to German Adverbs of Time, Manner and Place | FluentU German Blog

Confused about German adverbs? In this post, we break down how to use the three main types: adverbs of time, manner and place. You’ll get plenty of examples and audio to…

7. Conjunctions

Conjunctions are words that connect phrases and clauses together in a sentence. In German, there are two types of conjunctions: coordinating and subordinating.

Coordinating

Coordinating conjunctions connect phrases and clauses without changing the sentence’s word order. Whatever comes after this type of conjunction will follow a normal sequence, as if it were its own sentence.

Here are two examples of coordinating conjunctions:

| Examples of German Coordinating Conjunctions | Example Sentence | English Translation |

|---|---|---|

| und (and) | Ich spiele Klavier und singe im Chor. | I play the piano and sing in the choir. |

| aber (but) | Das Essen ist lecker, aber es ist zu teuer. | The food is delicious, but it is too expensive. |

Subordinating

Subordinating conjunctions are used when there’s a dependent clause involved.

When the sentence starts with the independent clause, then the subordinating conjunction would introduce the dependent clause. In the dependent clause, the conjugated verb is pushed to the end.

Putting the subordinating conjunction at the start of a sentence will also change the word order of the concluding independent clause. The inverted word order takes effect—the conjugated verb is pushed to the front.

| Examples of German Subordinating Conjunctions | Example Sentence | English Translation |

|---|---|---|

| bis (until) | Du darfst nicht gehen, bis du gegessen hast. | You may not leave until you have eaten. |

| weil (because) | Weil ich krank bin, muss ich Medikamente kaufen. | Because I'm sick, I must buy medicine. |

German Subordinating Conjunctions | FluentU German Blog

A subordinating conjunction in German connects a dependent clause to a main clause. Read on to find out about how subordinating conjunctions work, including proper word…

8. Prepositions

Prepositions are words that describe a noun in relation to something else. Typically, prepositions describe position, movement or timing.

German prepositions can be categorized according to the cases they utilize. The nouns that follow these prepositions take on different cases.

Accusative

The noun that immediately follows these prepositions must use the accusative case. For example:

durch — through

Ich gehe durch den Tunnel.

I walk through the tunnel.

Dative

Dative prepositions work the same way, but take the dative case instead. That means you have to watch out for those article and adjective endings! For example:

mit — with

Ich gehe mit meinem Freund in den Supermarkt.

I go to the supermarket with my boyfriend.

Genitive

The use of prepositions in the genitive is becoming increasingly rare, at least in spoken conversation where the dative is often used instead. However, they do appear in more formal contexts, so it’s good to know them regardless.

wegen — because of

Wegen des Sturms können wir nicht spielen.

Because of the storm we can’t play.

Two-way

In German, these are called Wechselpräpositionen ( Wechsel means “switch”). They’re appropriately named, because these prepositions can use either the accusative or dative case, depending on the context.

Sounds complicated, I know! Luckily, there’s a general rule to figure out which case should be used. The accusative is used for motion or direction, while the dative is for describing position or an object’s static location.

Here’s an example with one two-way preposition:

auf — on, onto, upon

Dative: Der Rucksack liegt aufdem Bett.

The backpack is on the bed.

Accusative: Ich lege den Rucksack aufdas Bett.

I put the backpack on(to) the bed.

German Prepositions | FluentU German Blog

German prepositions are useful words for building sentences, but their rules can be tricky if you’re new to them. So check out our ultimate guide to learning German…

9. Moods

Moods describe the nature and tone of the verbs used in a sentence, so that whoever hears it would understand the speaker’s intentions.

Indicative

The indicative mood ( der Indikativ ) is what you’ll be using most of the time. They’re appropriate for matter-of-fact sentences, or ones that simply express facts, opinions or questions. The indicative is also used to describe things that have happened, is happening or would happen.

Declarative Statements

Declarative statements are the sentences that just relay information. For example:

| Examples of Declarative Sentences | English Translation |

|---|---|

| Er kommt zu spät. | He's late. |

| Das überrascht mich nicht. | That doesn't surprise me. |

| Ich glaube, er hat uns vergessen. | I think he forgot about us. |

German Moods: Indicative, Imperative, Subjunctive | FluentU German Blog

German moods are an essential part of German grammar, so let’s take them on! Here’s your crash course to the indicative, imperative and subjunctive moods.

Interrogative Statements

Interrogative statements are sentences that pose questions. From a declarative statement, it’s pretty easy to form question statements—you move the conjugated verb to the first position of the sentence, followed by the subject, then the predicates or objects (if any):

| Examples of Interrogative Statements | English Translation |

|---|---|

| Kommt er zu spät? | Is he late? |

| Überrascht dich das? | Does that surprise you? |

| Meinst du, er hat uns vergessen? | Do you think he forgot about us? |

If an auxiliary verb is involved, then that auxiliary verb (conjugated) would take the first position instead.

While the translations for the above examples include the word “does” and “do,” this isn’t really the word being used. The German verb for “to do” isn’t utilized in most interrogative statements, since all that’s needed is the conjugated main verb.

But what about those “W-questions” asking about the who, what, when, where, why and how? These are known as “question pronouns,” and in German, they’re called W-Wörter (W-words). The six most common ones are:

| Most Common W-Wörter (W-words) | English Translation |

|---|---|

| Wer | Who |

| Was | What |

| Wann | When |

| Wo | Where |

| Warum | Why |

| Wie | How |

If you’re using a W-word in a question, then it would take the first position, followed by the main conjugated verb.

Imperative

This mood is for commands and orders. The imperative will solely use pronouns meant for directly addressing others: du (you), ihr (you, plural), wir (we) and Sie (you, formal). So, you’ll only have to worry about the conjugations related to those pronouns!

Forming the imperative involves putting the conjugated verb at the front of the statement. However, for du commands, the conjugated verb would have its ending (-st or –t) dropped.

Gib mir das Buch!

Give me the book!

Sie, ihr and wir commands use the simple present tense verb conjugations. Also, for the polite Sie commands, the pronoun must appear.

Lesen Sie bitte die Unterlagen.

Please read the documents.

The German Imperative | FluentU German Blog

The German imperative can come in handy when you least expect it. Take the plunge with this easy-to-use guide to the German imperative. We’ll show you how to build…

Subjunctive (der Konjunktiv)

The subjunctive ( der Konjunktiv ) is where we enter the esoteric realm of possibility and hearsay. There are two categories of the German subjunctive: Konjunktiv 1 and Konjunktiv 2.

Subjunctive 1

Konjunktiv 1 is used for indirect speech. In other words, someone’s words are being quoted or reported by another.

To form this mood, you’ll have to take the stem of the verb (in present tense) and add specific endings. These endings are the same for every verb except sein , which has its own unique forms.

Here are some examples of Konjunktiv 1 at work:

Sarah sagte, sie sei müde.

Sarah said she is tired.

Sarahs Mütter sagte, sie müsse mehr schlafen.

Sarah’s mother said she must sleep more.

Subjunctive 2

Konjunktiv 2 is used to express speculations, imaginings and hypotheticals. There are two main ways to accomplish this mood.

The first way is by using special conjugations of the main verb, and conveniently, these conjugations resemble the simple past conjugations. Vowel umlauts may also be added.

The second way is by utilizing the auxiliary verb werden . This verb will receive special conjugations that will automatically imply the Konjunktiv 2 mood—i.e., something “would” occur.

Here’s a sentence that utilizes both of these methods:

Wenn ich das Geld hätte, würde ich den Computer kaufen.

If I had the money, I would buy the computer.

The German Subjunctive | FluentU German Blog

The German subjunctive can be confusing for some learners—but fear not! This guide will explain everything you need to know about the subjunctive in German, including…

10. Word Order

At this point, you’ve seen several examples of how word order can work in German sentences. Sometimes, they’re in the basic Subject-Verb-Object format. Other times, they’re inverted and push the subject or a verb elsewhere.

As a quick refresher, here are some of the core elements that you should watch out for when considering word order:

- Conjunctions (especially subordinating conjunctions)

- Adverbs (especially if there are different types of adverbs)

- Verbs (especially if there are more than one)

By far, adverbs may prove to be the trickiest when figuring out the correct sentence word order. As a general guide, remember the rule of TMP: time, manner, place.

German Sentence Structure: The Simple Guide to German Word Order | FluentU German Blog

Tackle German sentence structure with this complete guide to proper German word order. Go beyond simple SVO sentences to discover the rules of TeKaMoLo and learn when to…

So there you have it: a speedrun of German grammar!

Take the time to study up a bit more on these concepts, and you’ll master them in no time!

And One More Thing...

Want to know the key to learning German effectively?

It's using the right content and tools, like FluentU has to offer! Browse hundreds of videos, take endless quizzes and master the German language faster than you've ever imagine!

Watching a fun video, but having trouble understanding it? FluentU brings native videos within reach with interactive subtitles.

You can tap on any word to look it up instantly. Every definition has examples that have been written to help you understand how the word is used. If you see an interesting word you don't know, you can add it to a vocabulary list.

And FluentU isn't just for watching videos. It's a complete platform for learning. It's designed to effectively teach you all the vocabulary from any video. Swipe left or right to see more examples of the word you're on.

The best part is that FluentU keeps track of the vocabulary that you're learning, and gives you extra practice with difficult words. It'll even remind you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)