German Subordinating Conjunctions

To become fluent in German, you’ll have to jump over quite a few grammar hurdles.

Here’s my back to basics guide for a grammar topic that even the most advanced German speakers can still struggle with: subordinate conjunctions.

Contents

- What Is a Subordinate Clause?

- Common German Subordinating Conjunctions

- Als

- Anstatt

- Bevor

- Bis

- Dass

- Damit

- Falls

- Hingegen

- Indem

- Nachdem

- Ob

- Obgleich

- Obwohl

- Seit

- Sobald

- Sodass

- Sofern

- Solange

- Sonst

- Soweit

- Sowie

- Statt

- Um

- Vorausgesetzt

- Während

- Wann

- Weil

- Wenn

- Wie

- Wo

- Word Order with German Subordinating Conjunctions

- And One More Thing...

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

What Is a Subordinate Clause?

A subordinate clause is, simply put, one of the building blocks of a compound sentence:

Complex sentence = main clause + subordinate clause

Here’s an example of how it works in a real sentence:

Ich muss schlafen, weil ich krank bin.

I need to sleep because I am ill.

In the above, we have a main clause: Ich muss schlafen (I need to sleep). Adding a second clause—or, subordinate clause—weil ich krank bin (because I am ill) lengthens the sentence, creating a complex sentence made up of two clauses.

One thing which always stumps beginners is the position of the verb in the subordinate clause. With the example weil ich krank bin, the verb—in this case ist (is)—is at the end of the clause. If we translate the sentence literally to English, it would read as, “I need to sleep because I ill am.”

Unlike English, the German language sends its verbs to the ends of subordinate clauses—it’s just something you have to accept without any real justification.

Admittedly, it can be really tricky to remember to send your verbs to the end, but with plenty of practice, you’ll eventually find it comes naturally.

Common German Subordinating Conjunctions

In the example above—Ich muss schlafen, weil ich krank bin—the use of weil (because) plays a really big part in the sentence. It’s the main reason why the verb is sent to the end of the clause. The grammatical term for the word is a “subordinate conjunction” as it conjoins the two clauses.

Subordinate conjunctions are words which send the verb to the end, whether in a subordinate clause or not. Unfortunately, there’s no simple rule you can learn to help you spot a subordinate conjunction.

Here are some of the most useful subordinate conjunctions:

Als

Meaning: As/when

Wir haben oft gespielt, als wir jung waren.

We played often when we were young.

Anstatt

Meaning: Instead of

Sie nahm den Bus, anstatt zu Fuß zu gehen.

She took the bus instead of walking.

Bevor

Meaning: Before

Ruf mich an, bevor wir in die Stadt gehen.

Give me a call before we go to town.

Bis

Meaning: Until

Ich warte, bis du wieder da bist.

I’ll wait until you’re back again.

Dass

Meaning: That

Ich hoffe, dass du uns noch lange erhalten bleibst.

I hope that you stay with us for a long time yet.

Damit

Meaning: So that

Ich nehme einen Tag frei, damit wir uns treffen können.

I’ll take the day off so that we can meet up.

Falls

Meaning: In case

Bring einen Regenschirm mit, falls es regnet.

Bring an umbrella in case it rains.

Hingegen

Meaning: On the other hand

Ich mag Fußball, hingegen mein Bruder bevorzugt Basketball.

I like football, on the other hand my brother prefers basketball.

Indem

Meaning: By

Er verbessert seine Sprachkenntnisse, indem er jeden Tag liest.

He improves his language skills by reading every day.

Nachdem

Meaning: After

Ich gehe einkaufen, nachdem ich meine Arbeit erledigt habe.

I go shopping after I finish my work.

Ob

Meaning: Whether

Weißt du, ob er noch kommt?

Do you know whether he is still coming?

Obgleich

Meaning: Although

Er nahm an dem Rennen teil, obgleich er verletzt war.

He participated in the race, although he was injured.

Obwohl

Meaning: Although

Ich habe kein Haustier, obwohl ich eine Katze möchte.

I don’t have a pet, although I would like a cat.

Seit

Meaning: Since

Seit ich hier lebe, bin ich nicht gefahren.

I haven’t driven since I have lived here.

Sobald

Meaning: As soon

Können Sie mich bitte anrufen, sobald es Ihnen möglich ist.

Can you please call me as soon as you can.

Sodass

Meaning: So that

Sie arbeitet hart, sodass sie ihre Ziele erreichen kann.

She works hard, so that she can achieve her goals.

Sofern

Meaning: In case, provided that

Sofern nicht anders vereinbart.

Except when it’s been agreed upon differently.

Solange

Meaning: As long as

Du kannst bleiben, solange du leise bist.

You can stay, as long as you are quiet.

Sonst

Meaning: Otherwise

Pass auf den Verkehr auf, sonst wirst du einen Unfall haben.

Watch out for the traffic, otherwise you will have an accident.

Soweit

Meaning: Insofar as

Soweit ich weiß.

As far as I know.

Sowie

Meaning: As well, as soon

Ich gebe dir Bescheid, sowie ich kenne.

I’ll let you know as soon as I know.

Statt

Meaning: Instead of

Er ging ins Kino, statt seine Hausaufgaben zu machen.

He went to the cinema, instead of doing his homework.

Um

Meaning: In order to

Er übt jeden Tag, um besser zu werden.

He practices every day in order to get better.

Vorausgesetzt

Meaning: Provided that

Vorausgesetzt, dass es nicht regnet, gehen wir spazieren.

Provided that it doesn’t rain, we will go for a walk.

Während

Meaning: During

Während der Stunde haben wir viel geredet.

We talked a lot during the lesson.

Wann

Meaning: When

Sag mir bitte, wann du ankommst.

Please tell me when you arrive.

Weil

Meaning: Because

Ich bin verspätet, weil ich verschlafen habe.

I am late because I slept in.

Wenn

Meaning: If

Wenn wir ins Kino gehen, können wir viel Popcorn essen.

If we go to the cinema we can eat a lot of popcorn.

Wie

Meaning: How

Lass mich morgen wissen, wie es dir geht.

Let me know tomorrow how you’re doing.

Wo

Meaning: Where

Sag mir bitte am Mittwoch, wo wir uns treffen.

Please tell me on Wednesday where we’re meeting.

Aside from getting familiar with the definitions, one way to help you remember these subordinating conjunctions is to get lots of exposure to native German speakers using them.

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Word Order with German Subordinating Conjunctions

The main point to remember is after a subordinate clause (one of the above words), the verb is always sent to the end.

But wait, did you notice another pattern emerging in some of the above examples? Can you see it in the examples for seit and wenn?

In both sentences the subordinate clause comes first. Nothing really changes—the verb is sent to the end as standard. But then after that, in the main clause, the verb moves around again. Let’s take another look:

Wenn wir ins Kino gehen, können wir viel Popcorn essen.

What should read wir können viel Popcorn essen by English logic actually doesn’t, as the verb (können) is moved to after the verb in the subordinate clause (gehen).

So that’s one other rule you need to remember with subordinate clauses—you need to invert your subject and your verb after a comma. Put simply, the word order when two clauses come together is usually: verb–comma–verb. If you write a verb with a comma after it, more often than not you will also need another verb right after the comma.

German subordinate conjunctions are one grammar topic you really need to be able to nail if you’re going to ace your German. Both your speaking and writing will depend on it!

If it all seems a bit too much at first, don’t worry. It is difficult for native English speakers as our verbs like to stay in one place! The key is—as with all things German, from conjugation to pronunciation—practice, practice and even more practice!

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing...

Want to know the key to learning German effectively?

It's using the right content and tools, like FluentU has to offer! Browse hundreds of videos, take endless quizzes and master the German language faster than you've ever imagine!

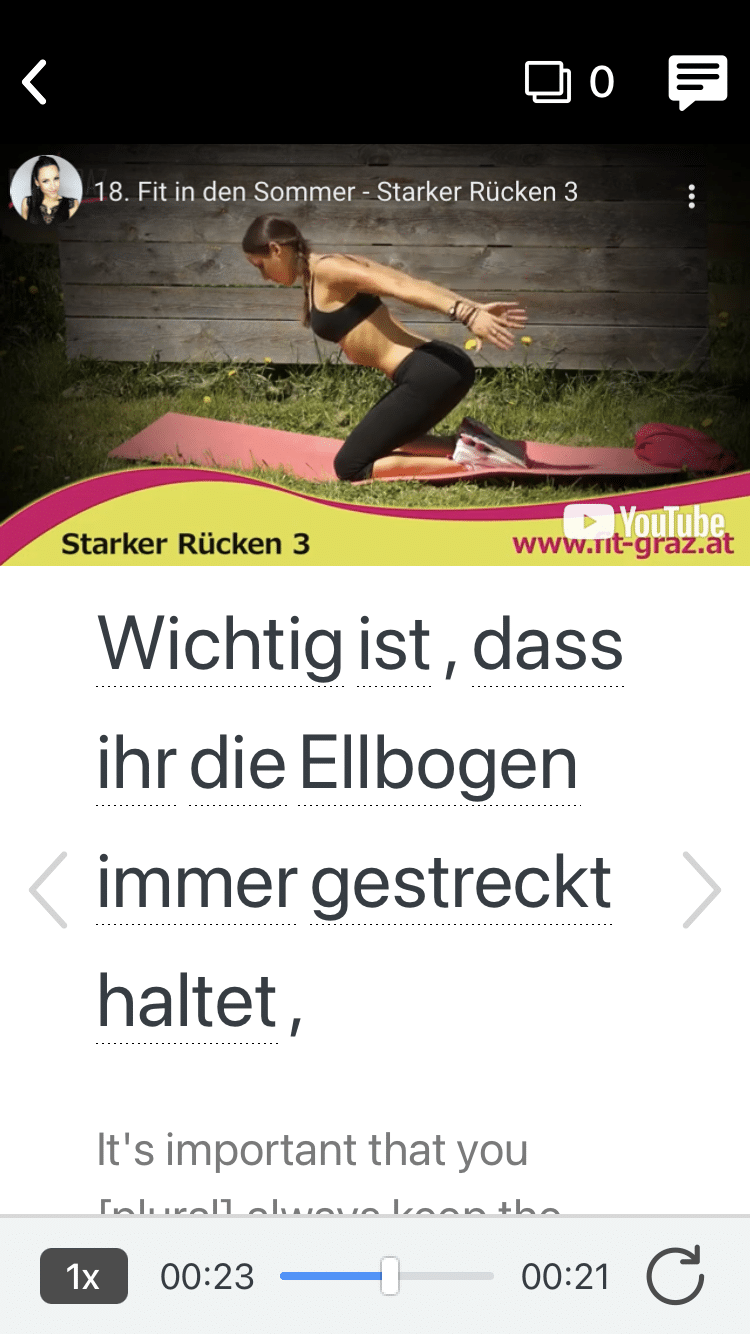

Watching a fun video, but having trouble understanding it? FluentU brings native videos within reach with interactive subtitles.

You can tap on any word to look it up instantly. Every definition has examples that have been written to help you understand how the word is used. If you see an interesting word you don't know, you can add it to a vocabulary list.

And FluentU isn't just for watching videos. It's a complete platform for learning. It's designed to effectively teach you all the vocabulary from any video. Swipe left or right to see more examples of the word you're on.

The best part is that FluentU keeps track of the vocabulary that you're learning, and gives you extra practice with difficult words. It'll even remind you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)