Pluscuamperfecto: The Spanish Tense That’s Way Easier Than It Sounds

Just looking at the longer name of the pluperfect in Spanish is scary enough, isn’t it?

In fact, when you get to the nitty-gritty of the Spanish pluscuamperfecto , it’s not that scary.

This article will give you a full crash course on how, when and why to use the Spanish pluperfect.

We even have some cool songs at the end where this tense is used, so stick around!

Contents

- What Is the Pluscuamperfecto?

- When Do We Use the Pluperfect in Spanish?

- How to Conjugate the Spanish Pluperfect

- Using the Pluscuamperfecto in Context: Tips and Tricks

- Differences Between the English Past Perfect and Spanish Pluperfect

- Cool Songs in Spanish to Practice the Pluscuamperfecto

- How to Practice the Pluperfect in Spanish

- And One More Thing…

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

What Is the Pluscuamperfecto?

The pluscuamperfecto—or the “past perfect” or “pluperfect” in English—is one of Spanish’s many tenses used to talk about actions that happened in the past.

The pluscuamperfecto is a compound tense, meaning it uses two verbs that are conjugated differently. Specifically, you conjugate the auxiliary verb haber and a past participle. The conjugation of haber depends on the subject of the sentence and whether the sentence requires an indicative or subjunctive verb.

Confused yet? Don’t worry: Conjugating the pluscuamperfecto is much easier than it sounds.

When Do We Use the Pluperfect in Spanish?

When talking about two actions that happened in the past

For example, take a look at this English sentence, paying particular attention to the verb conjugated in the past perfect.

John had already left when Sarah arrived.

This sentence deals with two actions, both of them in the past: John leaving, and Sarah arriving. Since John left before Sarah arrived, we must use the past perfect to talk about John leaving.

The Spanish indicative pluscuamperfecto works the same way. For example, the previous sentence translated into Spanish would read:

John ya había salido cuando llegó Sarah.

(John had already left when Sarah arrived.)

In this sentence, the verb había salido (had left) is an example of an indicative pluscuamperfecto verb.

The subjuntivo del pluscuamperfecto (past perfect subjunctive) is a little more complicated for English speakers.

Here’s a rundown on when and how to use subjunctive verbs in case you need it, but to sum it up:

| When to use the subjunctive form of the pluscuamperfecto | Example sentences |

|---|---|

| 1. When talking about emotions, desires or other subjective feelings in the past. | Quería que lo hubieras hecho ya.

(I wanted you to have already done it.) Estaba triste de que ella se hubiera ido sin despedirse. (I was sad that she had gone without saying goodbye.) |

| 2. With the phrase ojalá to express a desire that something would have happened in the past. | Ojalá hubiéramos ido.

(I wish we had gone.) |

| 3. In “if clauses” used to describe impossible situations, paired with either the past conditional or present conditional. * | Si hubiera sabido, no habría dicho nada.

(If I had known, I wouldn’t have said anything.) Si no hubiera comido tanto, iría contigo al restaurante. (If I hadn’t eaten so much, I would go with you to the restaurant.) |

*Note: In colloquial Spanish, you can frequently hear the conditional verb replaced with a second verb conjugated in the pluscuamperfecto. For example:

Si hubieras dormido más, no hubieras tenido tanto sueño.

(If you had slept more, you wouldn’t have been so tired.)

When substituting the preterite

Just as the pluperfect can be substituted with the preterite, the same can happen the other way around.

Although the substitution “pluperfect → preterite” occurs much more often than the “preterite → pluperfect” one, the latter can still take place, especially if you want to make the sentence slightly more formal:

| Preterite | Pluperfect |

|---|---|

| El profesor entró cuando los alumnos se sentaron.

(The professor came in when the students sat down.) | El profesor entró cuando los alumnos se habían sentado.

(The professor came in when the students had sat down.) |

| Desayuné cuando mi hermano terminó.

(I had breakfast when my brother finished.) | Desayuné cuando mi hermano había terminado.

(I had breakfast when my brother had finished.) |

Be careful when making this substitution, though. Bear in mind which action happened first, so that you don’t change the wrong verb.

For example:

Bebí el vino de la botella que había abierto un día antes. (I drank the wine from the bottle I had opened one day before.)

First, you open the bottle (past perfect), then you drink the wine. This makes sense.

On the other hand:

Había bebido el vino de la botella y después la abrí. (I had drunk the wine from the bottle and then I opened it.)

Although there is no grammatical error in the sentence, it’s impossible to drink the wine before opening the bottle. This doesn’t make sense.

Lastly, be careful when substituting the preterite for the pluperfect, and make sure you don’t change the whole meaning of the sentence. If the meaning changes when you change the verb form, this means the substitution can’t be done:

| Preterite | Pluperfect |

|---|---|

| Cuando llegamos, la película empezó.

(When we arrived, the film started.) | Cuando llegamos, la película había empezado.

(When we arrived, the film had started.) |

As you can see, in the preterite example, the sentence implies that the film started the moment “we” arrived. The second, on the other hand, says that, by the time “we” arrived, the film had already started. Maybe it’s already five to 10 minutes in—you get the idea.

When substituting the present perfect in indirect speech

Simply put, the difference between direct and indirect speech is that direct speech gives you the literal words someone is uttering/has uttered, while indirect speech consists of someone repeating those same words later in time.

There are many changes in pronouns, time adverbs and verb tenses (among others) when using the indirect speech, but for the purposes of this post, we’re going to concentrate on the present perfect.

When someone says something in the present perfect, change that tense to the pluperfect when repeating their words:

| Direct | Indirect |

|---|---|

| He ido al cine tres veces esta semana.

(I have gone to the cinema three times this week.) | Dijo que había ido al cine tres veces esa semana.

(He said he had gone to the cinema three times that week.) |

| Hemos comprado naranjas y limones.

(We have bought oranges and lemons.) | Dijeron que habían comprado naranjas y limones.

(They said they had bought oranges and lemons.) |

When talking about new experiences in the present

The pluperfect in Spanish is used to talk about the present—and so is the English past perfect!

We know we have to use the present perfect when we talk about our life experiences so far:

Nunca he visto un tiburón. (I have never seen a shark.)

No hemos estado nunca en España. (We have never been to Spain.)

But what happens when that changes? How can you say you have finally seen a shark? Or that this is your first time visiting Barcelona? By substituting the present perfect for the pluperfect!

Have a look:

Nunca había visto un tiburón. (I had never seen a shark. [But I am looking at one at the moment.])

No habíamos estado nunca en España. (We had never been to Spain. [But we are in Barcelona now, and oh boy, is it pretty!])

How to Conjugate the Spanish Pluperfect

Recall that the pluscuamperfecto is a compound tense that requires two verbs: haber and a past participle. Before we start putting the two together, let’s review past participles.

Past Participles

In English, we use past participles in the present perfect, past perfect and passive tenses. For example, in the phrase “Andy had seen,” the past participle is “seen.” In the phrase “It was eaten,” the past participle is “eaten.”

In Spanish, we use past participles in the present perfect and past perfect tenses. Forming regular past participles is simple: Take the infinitive, chop off the –ar, –er or –ir ending and add one of the following endings:

| Type of verb | Ending | Example |

|---|---|---|

| -ar | -ado | hablar

(speak) → hablado

(spoken) |

| -er | -ido | comer (eat) → comido (eaten) |

| -ir | -ido | dormir (sleep) → dormido (slept) |

Simple, right? Well, kind of. Conjugating regular past participles is easy, but there are many irregular past participles to look out for. Unfortunately, you have no choice but to memorize these irregulars.

Many irregular past participles take on the endings –to and –cho. Here are some of the most common ones.

| -to Spanish Past Participles | English Translation |

|---|---|

| roto | broken |

| muerto | died |

| escrito | written |

| abierto | opened |

| vuelto | returned |

| -cho Spanish Past Participles | English Translation |

|---|---|

| dicho | said |

| hecho | done/made |

| predicho | predicted |

| deshecho | undone |

| satisfecho | satisfied |

Some important irregular past participles end in –sto, such as visto (seen) and puesto (put).

Now that we have sorted out past participles, learning to conjugate the pluscuamperfecto in the indicative and subjunctive moods will be a breeze.

Indicative Pluscuamperfecto

In the indicative, we conjugate haber in the imperfect tense, like this:

- Yo había

- Tú habías

- Él/Ella/Usted había

- Nosotros habíamos

- Vosotros habíais

- Ellos/Ellas/Ustedes habían

All you have to do is use one of these conjugations of haber plus the desired past participle.

Ellos ya habían comprado las entradas cuando se canceló el concierto.

(They had already bought the tickets when the concert was canceled.)

Yo había querido pollo, pero me gustó la ternera.

(I had wanted chicken, but I liked the steak.)

Subjunctive Pluscuamperfecto

This time, you conjugate the auxiliary verb haber in the imperfect of the subjunctive.

- Yo hubiera / hubiese

- Tú hubieras / hubieses

- Él/Ella/Usted hubiera / hubiese

- Nosotros hubiéramos / hubiésemos

- Vosotros hubierais / hubieseis

- Ellos/Ellas/Ustedes hubieran / hubiesen

For example:

Si hubiéramos llegado tarde, no habríamos podido entrar.

(If we had arrived late, we wouldn’t have been able to enter.)

Ojalá me hubiese hecho caso.

(If only he had listened to me.)

Using the Pluscuamperfecto in Context: Tips and Tricks

Pluscuamperfecto With Pronouns

When conjugating the Spanish pluperfect, remember to place direct, indirect and reflexive pronouns before the conjugated form of haber.

For example, to use the reflexive verb casarse (to get married) in the past, you’d have to conjugate it like this:

Ella se había casado antes de cumplir 19 años.

(She had gotten married before she turned 19.)

With direct or indirect object pronouns, the conjugations look like this:

Les había dicho la contraseña.

(I had told them the password.)

Alternatively, you could write an even shorter sentence:

Se la había dicho. (I had told it to them.)

Let’s have one more example:

Todavía no lo habían terminado cuando me fui.

(They still hadn’t finished it when I left.)

Pluscuamperfecto Questions

To ask questions in the Spanish pluperfect tense, the subject of the sentence can be placed before or after the verb.

¿Habían estudiado los estudiantes antes del examen?

(Had the students studied before the exam?)

¿La escuela no había cerrado mucho antes del incendio?

(Hadn’t the school closed down long before the fire?)

¿Había dicho tu madre a qué hora tenías que llegar?

(Had your mother said what time you had to arrive?)

Pluscuamperfecto Time Prepositions

When dealing with pluscuamperfecto verbs, particularly the indicative form, you’ll often come across certain prepositions of time. Some of them are:

| Spanish Time Preposition | English Translation | Example Sentence |

|---|---|---|

| Ya | Already | Ya lo había dicho dos veces.

(I had already said it twice.) |

| Antes

Antes que Antes de Antes de que | Before | Lo habían visto antes.

(They had seen it before.) Habíamos salido antes que ellos. (We had left before them.) Había comido una pizza antes de jugar al fútbol. (He had eaten a pizza before playing football.) Él había llegado antes de que lloviera. (He had arrived before it rained.) |

| Cuando | When | Ya habíamos empezado cuando llegaron.

(We had already started when they arrived.) |

| Nunca | Never | ¡Nunca lo había visto!

(I had never seen it!) |

| Todavía | Still | Todavía no había fregado los platos cuando llegó su madre.

(He still hadn’t washed the dishes when his mom arrived.) |

Differences Between the English Past Perfect and Spanish Pluperfect

Spanish doesn’t allow you to separate había from the past participle.

While English allows adverbs to appear between “had” and the past participle, Spanish will never let you separate había from the past participle. If you want to add an adverb, add it at the beginning or the end of the sentence or before/after the verb—but never between both verb forms:

Ya había comido cuando llegaste. (I had already eaten when you arrived.)

Ella nunca había visto a un chico tan guapo. (She had never seen such a handsome guy.)

Habíamos acabado ya cuando el teléfono sonó. (We had already finished when the telephone rang.)

If there are pronouns in the sentence, they will always go before the pluperfect.

English adds its pronouns after the verb. Spanish, however, likes them before the verb:

No los había visto todavía. (I had not seen them yet.)

Le había dicho la verdad un año antes. (He had told her the truth one year before.)

La habían cerrado a las 7 de la tarde. (They had closed it at 7 p.m.)

Always follow these two rules and your Spanish pluperfect sentences will be perfect.

Cool Songs in Spanish to Practice the Pluscuamperfecto

Learning song lyrics can be a great way to hone your knowledge of Spanish grammar. I’ve found that singing and listening to music is especially helpful for nailing down those irregular verbs. Once you hear an irregular conjugation over and over again in a song, it’ll stick in your mind forever.

Here are some songs that’ll help you master the pluperfect in Spanish!

Indicative Pluscuamperfecto

- Franco de Vita, “Ya Lo Había Vivido” — This song contains a number of instances of the pluscuamperfecto, including a variety of irregular and regular verbs.

- Jorge Rojas, “Me Había Olvidado” — The song title “Me Había Olvidado” provides an example of correct pronoun placement when using the pluscuamperfecto—always before the conjugation of the verb haber.

Subjunctive Pluscuamperfecto

- Carlos Rivera, “El Hubiera No Existe” — This song’s title at first appears to be a grammatical error (where’s the past participle?), but it’s really a play on the grammar. It translates approximately to “‘Would Have’ Doesn’t Exist.” Listen for a number of different examples of when to use the subjunctive pluscuamperfecto to express impossible situations in “if clauses.”

- Christina Aguilera featuring Luis Fonsi, “Si No Te Hubiera Conocido” — This lovely duet, whose title translates to “If I Had Never Met You,” showcases a variety of situations in which to use the subjunctive pluscuamperfecto. It showcases “if clauses” in which the subjunctive pluscuamperfecto is paired with a conditional verb.

How to Practice the Pluperfect in Spanish

Maybe after reading this article, you’ll think, “¡Vaya! ¡Nunca había aprendido el pluscuamperfecto!” (Wow! I’d never learned the Spanish past perfect!) Perhaps, on the other hand, you’re thinking, “Qué aburrido, ya había aprendido todo eso.” (How boring, I’d already learned all of that.)

Either way, after reading this post, you now have the tools to construct either of these sentences—and any other sentence in the pluscuamperfecto tense! (See, it wasn’t as hard as the name sounds, was it?)

To keep practicing, you can use:

- A book from the reputable “Practice Makes Perfect” series. “Practice Makes Perfect: Complete Spanish Grammar” and “Practice Makes Perfect: Spanish Verb Tenses” both include sections about the pluscuamperfecto and plenty of opportunities to practice using them.

- A Spanish movie on Netflix. For more informal practice, sit down with a big bowl of popcorn, relax and enjoy the film! Just remember to listen for the pluscuamperfecto in speech while you’re at it.

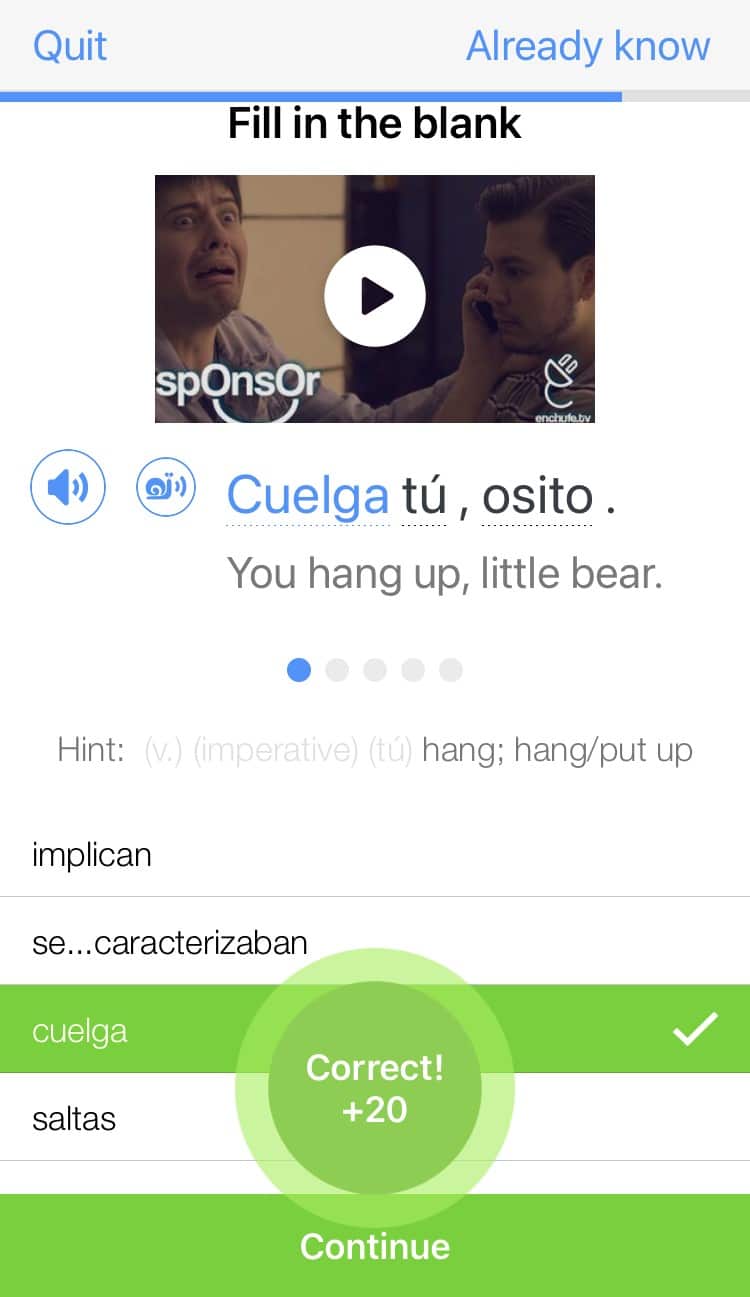

- A virtual immersion platform. FluentU, for example, has annotated captions with nuanced definitions and context for all of its videos, which can help you understand why a word is being used in a particular way.

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. If you decide to sign up now, you can take advantage of our current sale!

Soon, my friends, your pluscuamperfecto will simply be perfecto !

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing…

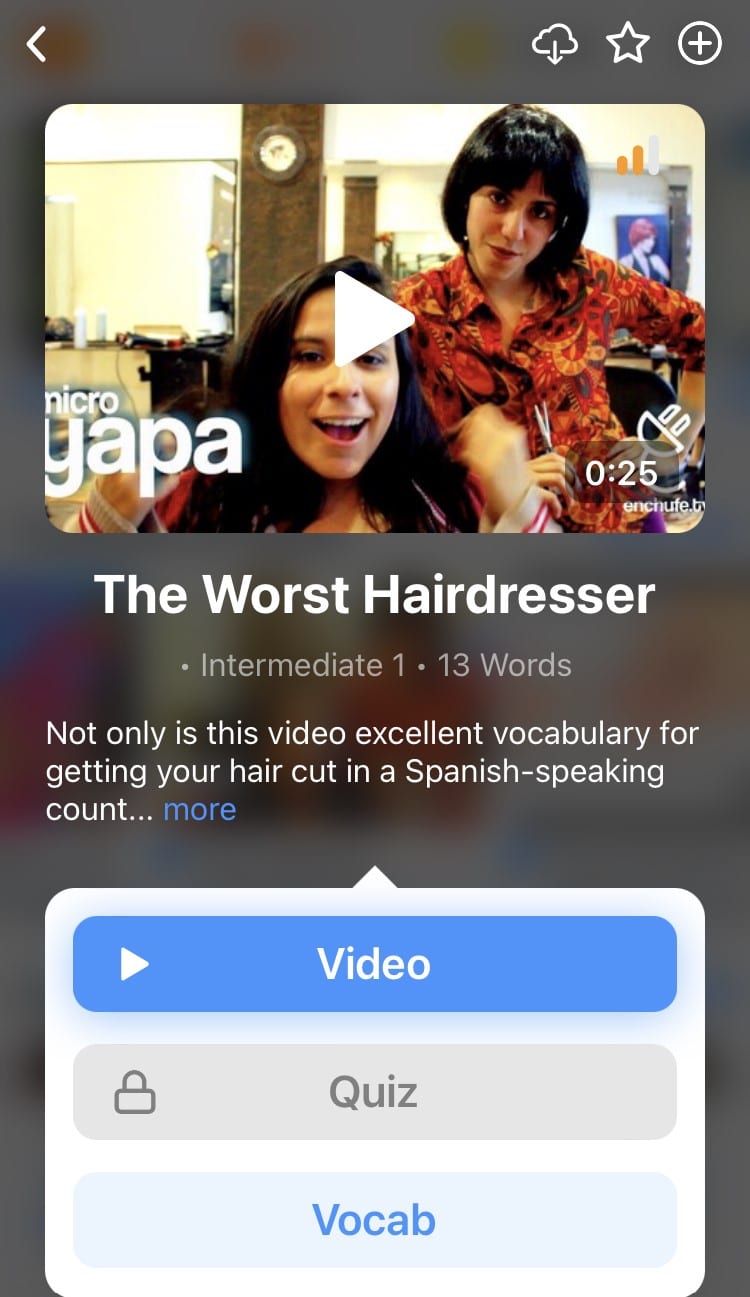

If you've made it this far that means you probably enjoy learning Spanish with engaging material and will then love FluentU.

Other sites use scripted content. FluentU uses a natural approach that helps you ease into the Spanish language and culture over time. You’ll learn Spanish as it’s actually spoken by real people.

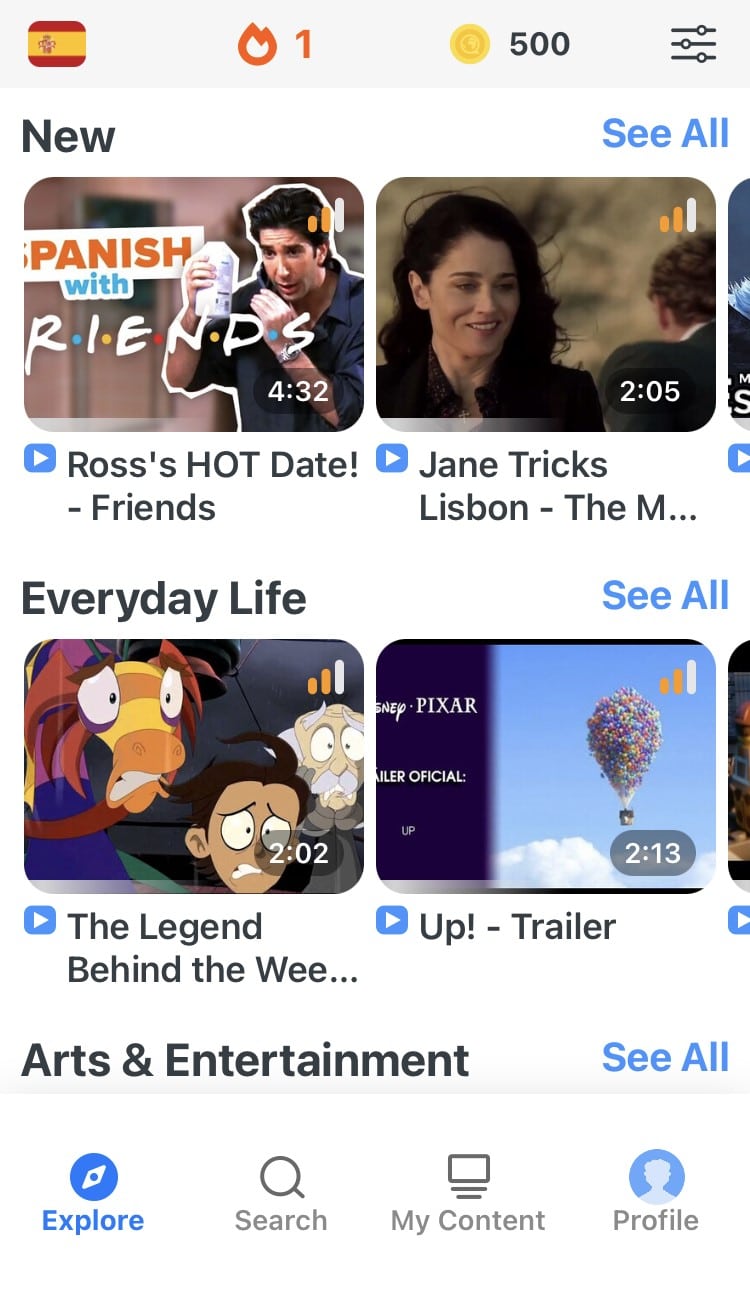

FluentU has a wide variety of videos, as you can see here:

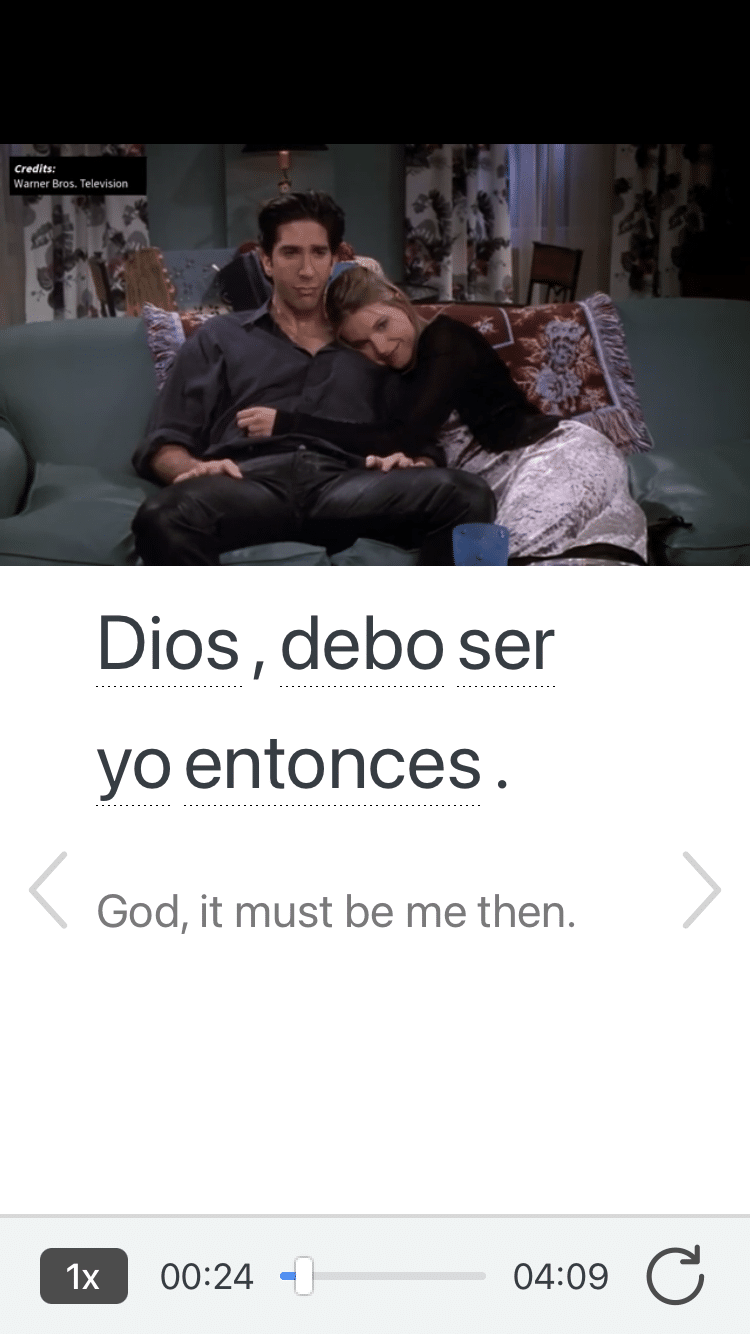

FluentU brings native videos within reach with interactive transcripts. You can tap on any word to look it up instantly. Every definition has examples that have been written to help you understand how the word is used. If you see an interesting word you don’t know, you can add it to a vocab list.

Review a complete interactive transcript under the Dialogue tab, and find words and phrases listed under Vocab.

Learn all the vocabulary in any video with FluentU’s robust learning engine. Swipe left or right to see more examples of the word you’re on.

The best part is that FluentU keeps track of the vocabulary that you’re learning, and gives you extra practice with difficult words. It'll even remind you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. Every learner has a truly personalized experience, even if they’re learning with the same video.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)