Ecuadorian Spanish in the Amazon, Galapagos Islands and Other Areas

Ecuador has it all: the Andes mountains, the Amazon, gorgeous beaches and the Galápagos. Three of the world’s 10 biodiversity “hotspots.” Five UNESCO Cultural and Natural Heritage Sites.

I’ve spent three years in this great little country, and I’m happy to report there’s always more to learn.

If you want to travel to Ecuador or speak with your Ecuadorian friends like you’re one of them, this post is for you.

Today, you’ll learn everything you need to know about Ecuadorian slang, regional variations and more.

Contents

- Regional Variations of Ecuadorian Spanish

- Essential Elements of Ecuadorian Spanish

- And One More Thing…

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Regional Variations of Ecuadorian Spanish

After arriving in this country that’s roughly the size of Colorado, prepare to be amazed at the amount of ethnic, cultural, ecological and linguistic diversity.

La Costa (The Coast)

People from here are known as costeños and are a fast-talking, slang-slinging bunch.

Traveling north along the coast—from the largest city in Ecuador (Guayaquil) to the predominantly African-Ecuadorian province of Esmeraldas—you’ll encounter tons of language and demographic variations.

The general key to speaking coastal Ecuadorian Spanish is to drop the letter s from the ends of your sentences. Oddly enough, in the southern province of El Oro, they do the exact opposite and add the letter s to many words, but this is the exception.

In Esmeraldas, the Spanish dialect exhibits many strong African influences.

In Guayaquil, the “ch” sound is sometimes pronounced as an elongated “sssh,” but this is viewed as being roughneck. Many guayaquileños use the sound facetiously or for emphasis.

In this video, you’ll hear several people try to imitate the the costeño accent (as well as the serrano accent, which we’ll learn about next).

La Sierra (The Mountains)

People in this region are known as serranos and speak with a musical, sing-songy lilt. They also tend to speak more slowly and clearly, enunciating every word very cleanly.

However, you’ll probably find plenty of Quechua words thrown into the mix, more so than on the coast.

Ecuador’s capital, Quito, is nestled in los Andes (the Andes), as is the historic city of Cuenca.

Small villages dotting the hillsides and valleys are predominantly occupied by la gente indígena quichua (Indigenous Quichua people).

Check out this short YouTube video to hear a girl talk in the serrano accent.

La Amazonia (The Amazon)

Here you’ll find a mix of gente indígena kichwa (Indigenous Kichwa people) and serranos. The general accent is somewhat similar to that of serranos—slower and more sing-songy.

(The Quichua and Kichwa groups use such different dialects of Kichwa that it’s sometimes difficult for them to understand one another.)

You’ll find Achuar, Shuar and Waorani people deeper in the jungle. They speak their respective indigenous languages, though many people in these communities also speak Spanish as a second language.

People who live throughout this region but come from other parts of Ecuador are often called colonos , reflecting residual colonization-era tension. The relationship between these indigenous and non-indigenous groups is sometimes a source of conflict.

Because of these reasons, the Spanish in this region is heavily mixed and accented with indigenous language.

If you’re in Tena, you’ll be hearing Kichwa.

In Puyo, you might also hear Shuar or Achuar languages in the mix.

Spanish is a relatively recent arrival in many rural communities and is mainly used as a second language for interacting with non-indigenous people. That means you’ll find plenty of people in older generations who speak little to no Spanish.

In this video, the man is speaking in the Amazonian accent:

Las Islas Galápagos (The Galapagos Islands)

The demographic here is similar to the coast, and the people speak just like costeños from the mainland.

Prepare to encounter lots of people working in the booming tourism industry. The upside to this is that the people there are well-versed in communicating in Spanish and English with visiting foreigners.

Other Curveballs

The complexity doesn’t end with these major regions.

In Guayaquil, the wealthy urbanites living in Samborondón (a luxurious and heavily-guarded gated community) speak with a musical accent closest to Argentinian Spanish.

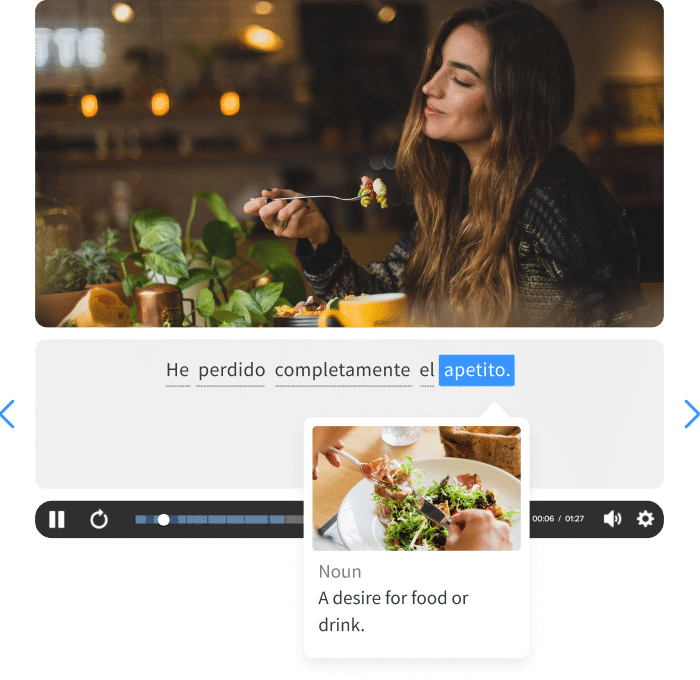

You can better understand how Ecuadorian Spanish (and other types of Spanish) sound by watching some authentic Spanish videos on FluentU.

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Essential Elements of Ecuadorian Spanish

Storytelling

You can’t speak Ecuadorian Spanish until you can tell a five-minute story with many exaggerated hand gestures.

Despite speaking near-fluent Spanish upon arrival, I was sorely disappointed with my success in socializing initially, simply because I couldn’t command the attention of my Spanish-speaking acquaintances and entertain them for even a few minutes.

This is especially important in Guayaquil and Quito. Here are a few pointers to prepare for when your friends are all eagerly saying “cueeeeeeenta” (tell me, spill it!) and you don’t want to let them down:

- Think of a hilarious story, something that happened to you that makes you giggle in retrospect. You’ll do better if you can be humble and make fun of yourself too.

- Try to tell this story to yourself out loud and stretch it out. Every few lines should have some sort of punchline that impresses, shocks or entertains people.

- Identify the keywords that you’re missing to describe the event or situation. Write these down and look them up for later use.

- Bonus points if you can stand up and act everything out, express the actions with your hands, make hilariously exaggerated facial expressions or do imitations of people’s voices.

People here love to share stories and experiences. It seems cold and strange not to divulge personal details. The more you share with your new Spanish-speaking friends, the more things they’ll share with you!

Being Cutesie

For Ecuadorians, making every single word diminutive (adding –ito/-ita to the end of words) does not sound overly saccharine.

Instead, it sounds normal and, when used strategically, extra polite.

“Tómate un cafecito, mijita.” (Drink a little coffee, sweetie)

“Espérate un poquitito.” (Please wait a little bit) — This one is more informal than the rest

“Un momentito, por favor.” (One moment, please)

“Ya mismito…” (Any minute now…)

“Sí, lo voy a hacer ahorita.” (Yes, I’m going to do it now.)

“¿Quieres tomar una colita?” (Would you to drink a soda?)

“Estoy medio enfermita así que me tomé una agüita.” (I’m kind of sick so I drank an herbal tea). — Notice that the –ita suffix actually changes the meaning of the word from water to herbal tea.

“¡Acolítame, pana!” (Help me out, buddy!) — The word acolítame (from acolitar) is a strange but tremendously popular Ecuadorianism synonymous with apoyame (support me).

All of the above are phrases that you will absolutely hear Ecuadorians say to you.

Warmth, Politeness and the Gentle “No”

As you may have gathered, Ecuadorians are very polite and humble in their speech. This is especially true for people you’re doing business with.

Overall, Ecuadorians are some of the warmest, kindest and most generous people you’ll ever meet, and they manage to take their kindness to extremes.

Because of this, they don’t want to say the word “no.”

People will often nod their heads, smile and say “sí, sí” even if they disagree with you, don’t understand your broken Spanish question or don’t know how to give you directions properly.

That’s why I live by the “rule of 3.” Don’t just ask one person. Ask three people that same question and take the answer that 2 of 3 people give you.

Hey, at least it’s great speaking practice!

Casual Racism

Ecuadorians tend to be far more open to discussing race and have no fear of being politically incorrect. This is often shocking to newcomers.

Casual racism takes two forms: nicknames and generalizations.

So, for nicknames, people are often referred to lovingly with things like la negrita (the black girl) or la chinita (the Chinese girl, the girl who looks Chinese, the girl with Chinese-looking eyes).

Western-looking people are often called la blanquita (the white girl) or la gringuita (the American girl).

You may notice that all of the above nicknames use diminutive suffixes, thus expressing affection. When someone is described with these words and they’re not made diminutive, this is more of a way to refer to someone descriptively without expressing personal connection or affection.

For example, la gringa might be a random foreigner who walked by the storefront yesterday, while mi gringuita might be used by a homestay mom to refer to her foreign exchange student.

Groups of people are primarily generalized with overarching terms like los negros (black people), los gringos (all Western-looking foreigners) and los chinos (all Asian people).

I advise you to look beyond the words the person uses and instead to their intentions. Do they mean to speak in a derogatory manner? Or is it just about the vocabulary that they grew up with?

Kichwa

Numerous indigenous groups once thrived in Ecuador. To this day, many communities celebrate Kichwa heritage and strive to keep their language and culture alive.

Not only is the strong presence of these communities felt, but many Ecuadorians recognize that they have descended from indigenous peoples to some extent. This rich heritage is a national point of pride, so it’s not surprising that Kichwa melds together with Spanish in Ecuador.

Quite a few common words and phrases come from Kichwa and are found in everyday Ecuadorian conversations.

Take a look at these Kichwa words which are used constantly by Ecuadorians:

- mishki (sweet) — You’ll often hear this in the context of tripa mishki (sweet tripe), which is a typical Ecuadorian dish.

- cuy (guinea pig) — We keep them as pets, but they’re raised for (very little) meat in Ecuador.

- achachai (cold) — Exclaim “achachai!” when you climb up Cotopaxi and start feeling chilly.

- arrarrai (hot) — You can shout “arrarrai!” (with those rolled rr‘s dramatically elongated) when you burn your hand on the stove.

- sumak (good, great, excellent) — This isn’t spoken as much, but it’s often seen in the names of hotels, hostels, resorts and restaurants.

- chuchaki (hungover) — Self-explanatory.

- mashi (friend) — Former President Rafael Correa posts from the Twitter handle @mashirafael and—fun fact—he speaks great Kichwa.

- chakra (small family farm) — Many people in rural areas have small farms owned by their immediate family to supply food for household consumption.

- ñaño (brother) — Ñaña is sister. You can also say ñañito or ñañita.

- wawa (baby) — Isn’t that a cute onomatopoeia?

- chicha (a fermented drink made from yucca—cassava root) — This is drunk by members of rural communities at all hours of the day. It keeps you full and gives you energy for the work day, but stronger batches can be quite alcoholic.

- cancha (field for sports) — You may have already learned this word, and now you know it’s derived from Kichwa!

- morocho (type of corn) — This corn is made into a thick, hot, sweet and deliciously creamy drink that goes by the same name, morocho.

- runa (person, being fully alive) — Runa is a beautiful Kichwa word used to refer to a person or community. This was previously used as a racial slur years ago (and sometimes crops up nowadays), but the true meaning of the word is being strongly reclaimed by indigenous communities today.

Loan Words

Like many parts of the Spanish-speaking world, you’ll discover that you can whip out many English loan words and have people understand you.

To name a few: cool, fresh, chill, relax and full.

All of these words mean they same things they do in English, with one slight exception.

The word full is informal and fun, so you’ll sound extra chill.

Take a look at all the various uses of full:

A: “¿Había mucha gente en la fiesta anoche?” (Were there a lot of people at the party last night?)

B: “¡Sí! ¡Full gente!” (Yes! There were tons of people!)

A: “Wow, me imagino que esa casa pequeñita estaba full.” (Wow, I imagine that tiny house was full!)

B: “Sí, man. ¡Full farra!” (Yeah, man. It was a total rager!) Farra is what you’d call a wild party.

Armed with all this awesome Ecuadorian Spanish, you have a way more colorful vocabulary to pack when you travel. Can you feel your Spanish horizons broadening yet?

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing…

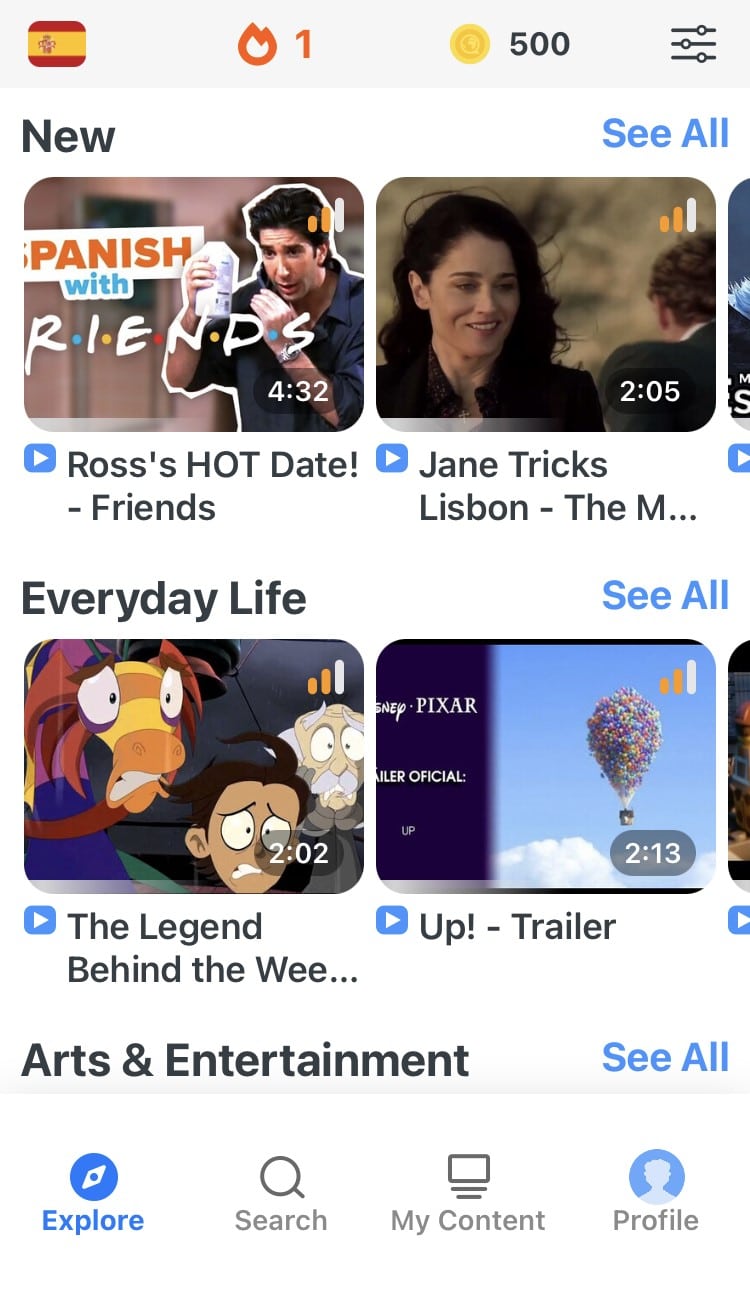

If you've made it this far that means you probably enjoy learning Spanish with engaging material and will then love FluentU.

Other sites use scripted content. FluentU uses a natural approach that helps you ease into the Spanish language and culture over time. You’ll learn Spanish as it’s actually spoken by real people.

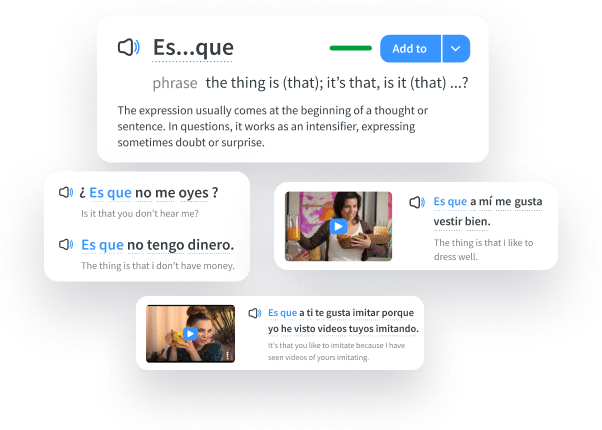

FluentU has a wide variety of videos, as you can see here:

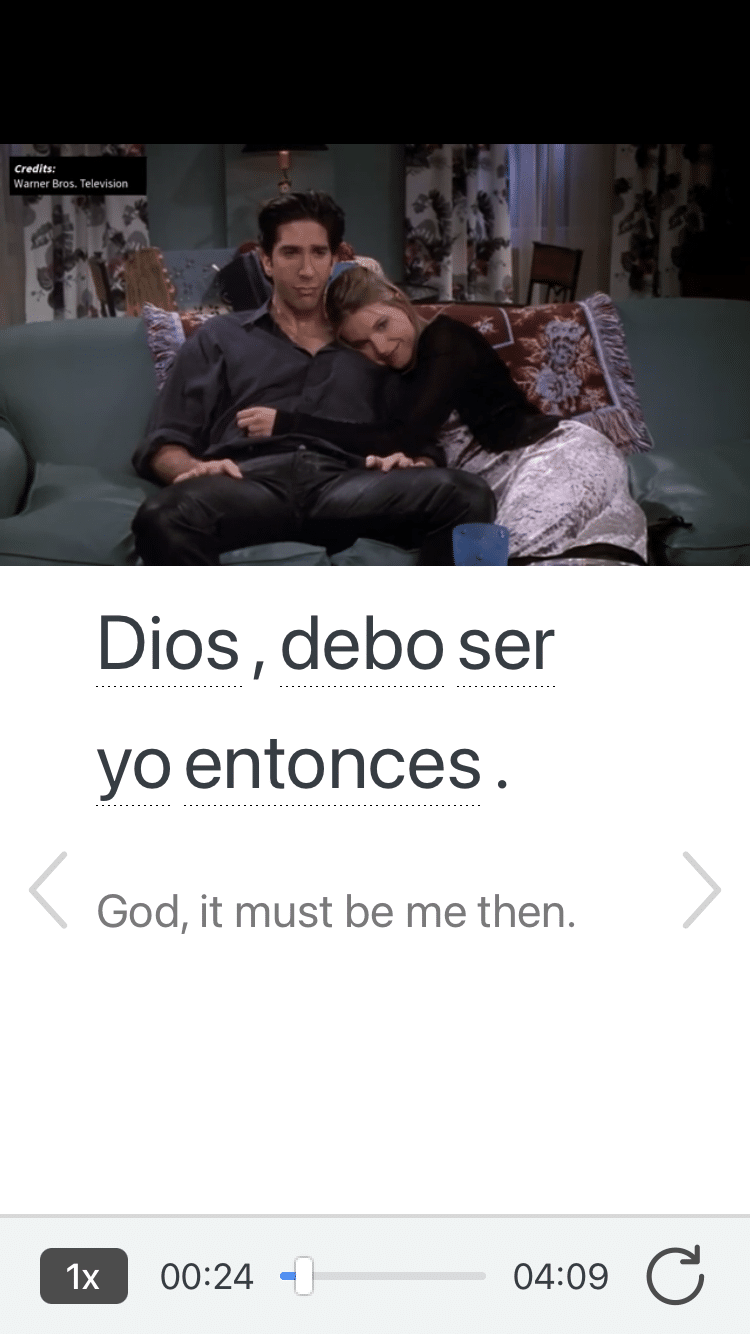

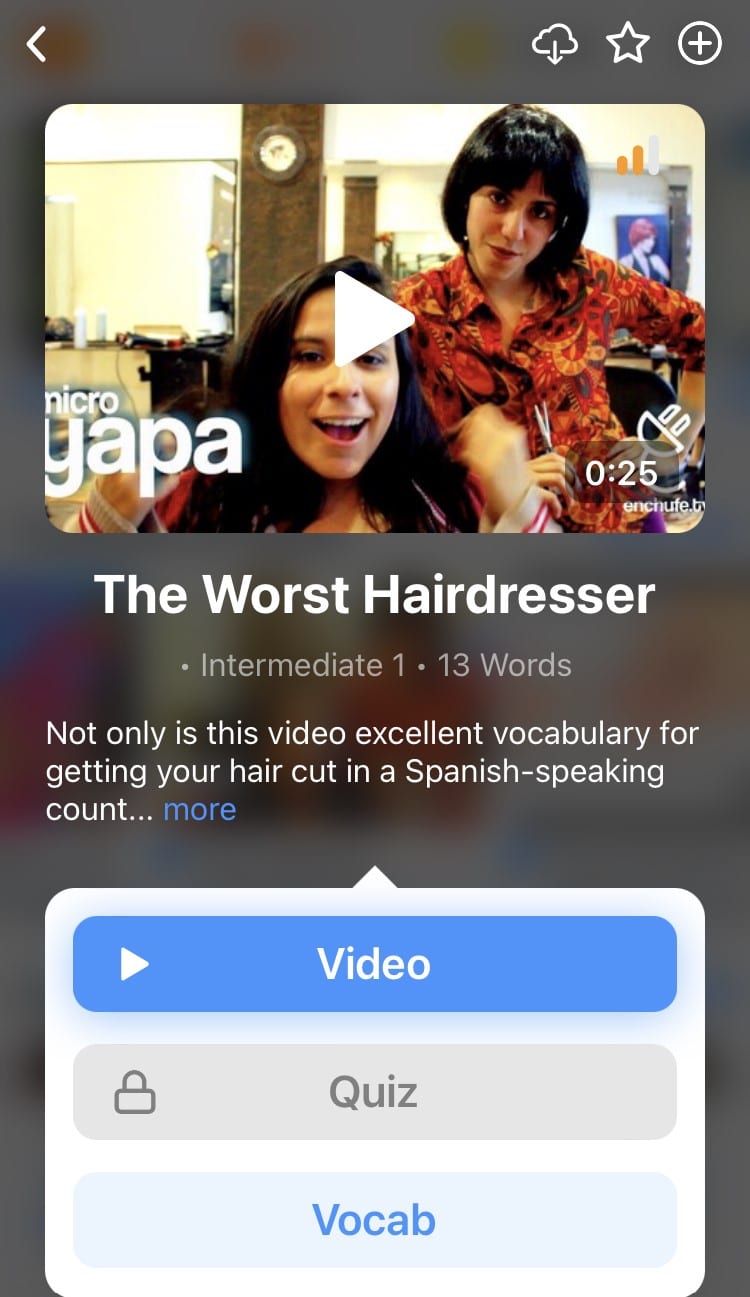

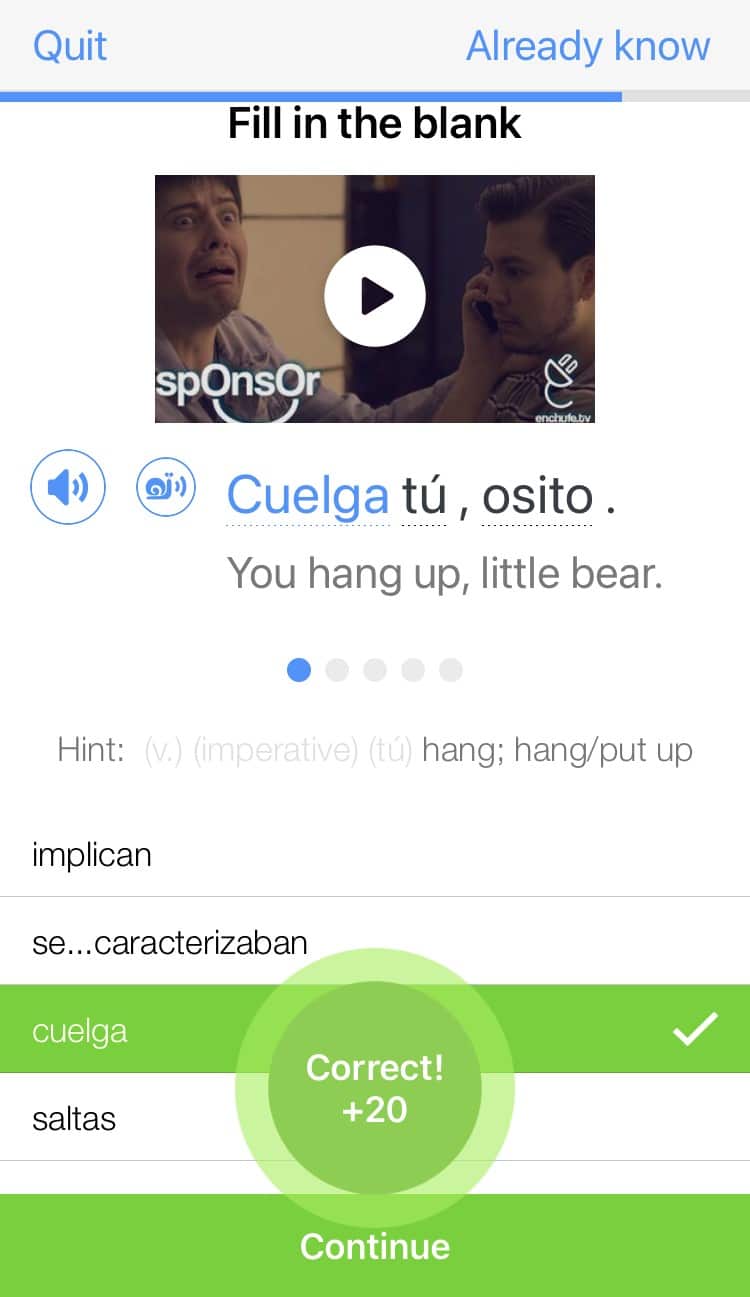

FluentU brings native videos within reach with interactive transcripts. You can tap on any word to look it up instantly. Every definition has examples that have been written to help you understand how the word is used. If you see an interesting word you don’t know, you can add it to a vocab list.

Review a complete interactive transcript under the Dialogue tab, and find words and phrases listed under Vocab.

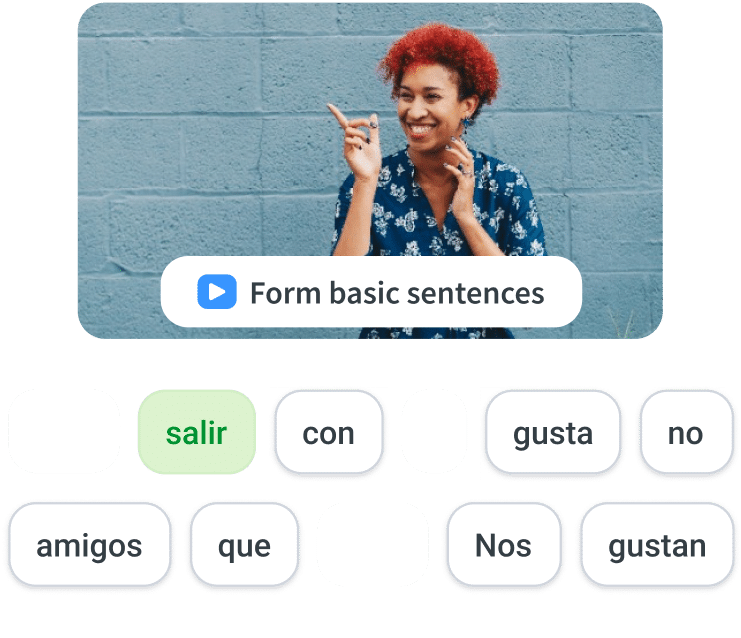

Learn all the vocabulary in any video with FluentU’s robust learning engine. Swipe left or right to see more examples of the word you’re on.

The best part is that FluentU keeps track of the vocabulary that you’re learning, and gives you extra practice with difficult words. It'll even remind you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. Every learner has a truly personalized experience, even if they’re learning with the same video.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)