Onyomi vs. Kunyomi: Because What You Kanji Isn’t What You Get

So, you just learned a brand new kanji character.

Then, you come across another weird word with that kanji read in a completely different way.

In some cases, a kanji can have more than seven readings.

This may seem overwhelming at first, but there’s a method to the madness.

Once you understand where all of this came from, you’ll understand more about how kanji readings work.

Contents

- The History Behind Japanese Kanji and Their Readings

- Onyomi and Kunyomi: What’s the Difference?

- When Should You Use Onyomi?

- When Should You Use Kunyomi?

- How to Learn Onyomi and Kunyomi Once and for All

- And One More Thing...

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

The History Behind Japanese Kanji and Their Readings

For a long time, Japan didn’t have a written language of its own.

Rather, kanji is believed to have made its way to Japan from China sometime between the fifth and eighth centuries AD. At least, that’s what the evidence suggests—we know that there were groups in Japan that studied the Chinese language around this time. (On another note, the katakana and hiragana writing systems came about in the ninth century AD.)

As you can imagine, any time a language translates from one culture to another, things get changed around. Because of word adoptions, trades and just your regular garden variety interpretations, Japanese became a language made up of many parts.

Of course, before its writing system developed into what it is today, Japan had a spoken language prior to the arrival of Chinese characters. The subsequent attempts to merge the two helped to create these natural variations in kanji readings.

Onyomi and Kunyomi: What’s the Difference?

As a result of the abovementioned history, Japanese learners have to adapt to the fact that there are two types of kanji readings: onyomi and kunyomi.

Onyomi translates roughly to “sound reading.” It means that the kanji is using the Japanese phonetic approximation of that character’s Chinese pronunciation. Kunyomi, on the other hand, is the fully Japanese version of the kanji reading.

For example, the onyomi reading of the character for “water” (水) would be すい , which almost sounds like the Chinese shuǐ. The kunyomi reading would be みず . Before Chinese characters were introduced to Japan, みず was how the native Japanese sounded out the word for “water” in their language. That pronunciation eventually merged with the Chinese character associated with that concept.

It’s worth noting that I used an oversimplified example to illustrate the main difference between onyomi and kunyomi. Chinese and Japanese words didn’t always have a one-to-one match, and over time, the Japanese language added its own connotations as needed. Hiragana was later added to kanji, tweaking readings and bringing more meaning to each kanji they’re associated with.

Now that you understand why Japanese words have onyomi and kunyomi readings, it’s time to talk about when to use each reading.

When Should You Use Onyomi?

- When you see multiple kanji strung together in a compound word. These words usually come from the original Chinese readings. Examples include 理解 ( りかい or “understanding”) and 短期 ( たんき or “short term”)

- When you see a word with no hiragana. See the same examples above.

- When you’re looking at a standalone kanji. If you see a kanji on its own, your go-to option should be one of the onyomi readings as with words like 一 ( いち or “one”) and 八 ( はち or “eight”).

When Should You Use Kunyomi?

- When you’re pronouncing family names (with a few exceptions). Examples include names like 木村 ( きむら ) and 藤井 ( ふじい ). This isn’t a hard-and-fast rule, though: names such as 陣内 ( じんない ), 伊藤 ( いとう ) and 佐藤 ( さとう ) are read in the onyomi style.

- When you’re pronouncing proper nouns that are the names of places (also with exceptions). You have 長野 ( ながの ), 旭川 ( あさひかわ ), 熊本 ( くまもと ) and 箱根 ( はこね ). On the other hand, places such as 北海道 ( ほっかいどう ) and 東京 (とうきょ う) are read aloud with the onyomi.

- When you see a single kanji followed by a hiragana character that makes up part of the word. You’ll see these frequently in adjectives and verbs. Think of 白い ( しろい or “white”) and 食べる ( たべる or “to eat”), for example.

By the way, the hiragana that follow kanji readings are called 送り仮名 ( おくりがな ). In fact, you’ll notice that 送りor “to send off” uses the kunyomi reading for the character 送! So 送り仮名 literally means “sending off letters.”

How to Learn Onyomi and Kunyomi Once and for All

The good news is that the rules I just laid out above apply to many cases. The bad news is that judging exactly when you need to use onyomi and kunyomi readings is something that is best learned through experience and frequent encounters with the Japanese language as it’s used by natives.

You need to listen to Japanese music, watch Japanese commercials and check out news reports. You can also use a language learning program like FluentU.

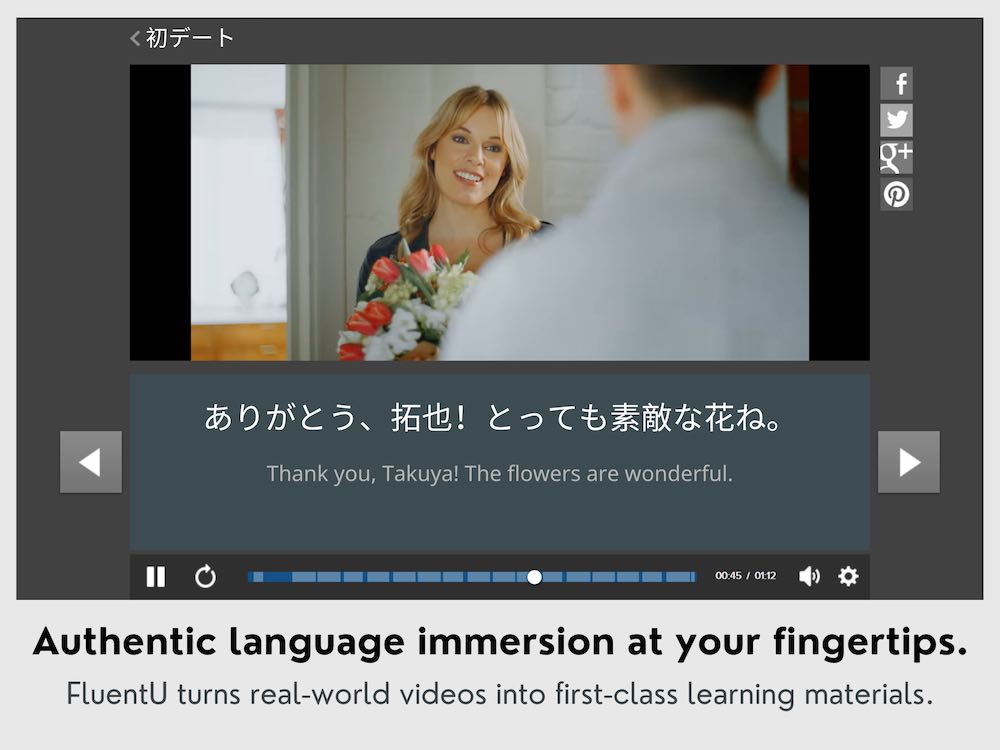

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

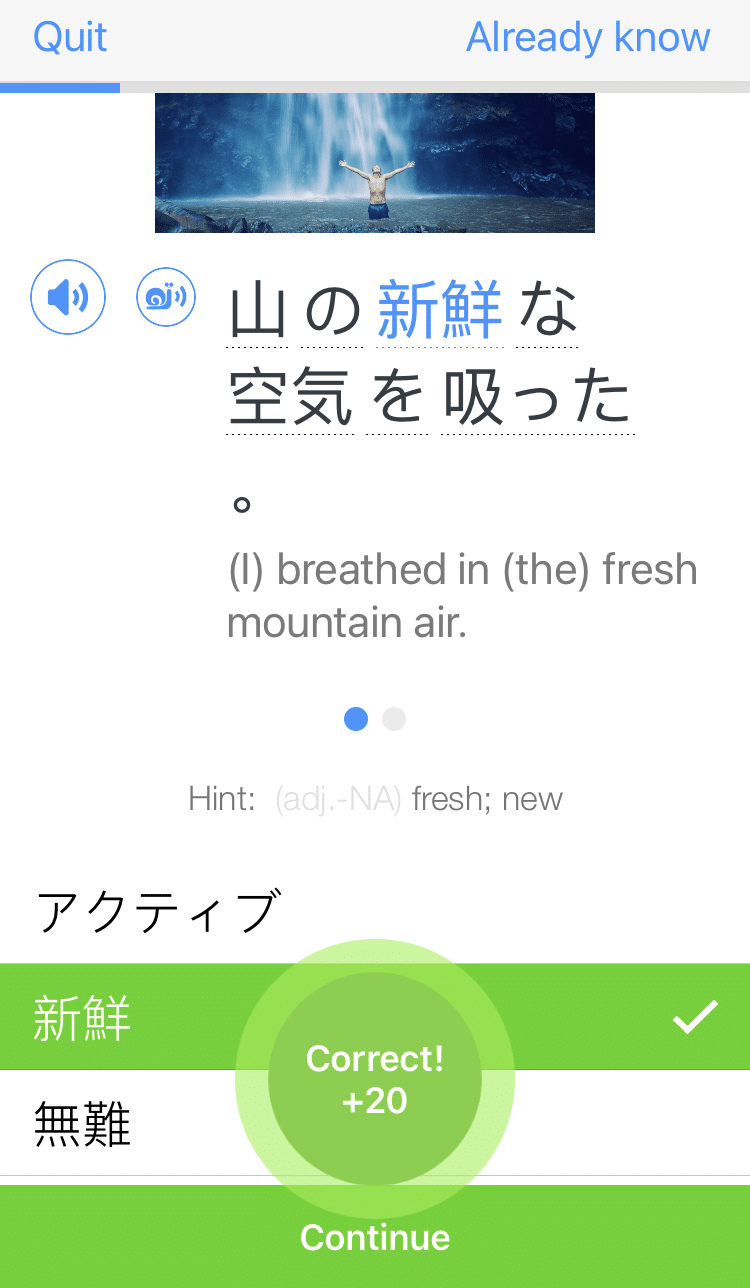

All you have to do is hover over any kanji in a video’s subtitles to instantly see its definition and pronunciation.

Whatever method you choose, the key is to learn new kanji and their proper readings in context to remember them better.

With practice, you’ll get better at choosing the right kanji readings at the right times.

Don’t be embarrassed to be wrong, and don’t be afraid to ask about words that you don’t know.

In time, as you get more familiar with the language, these differences will become second nature.

All languages have their quirks, and in the end, that’s what makes them unique and special.

And One More Thing...

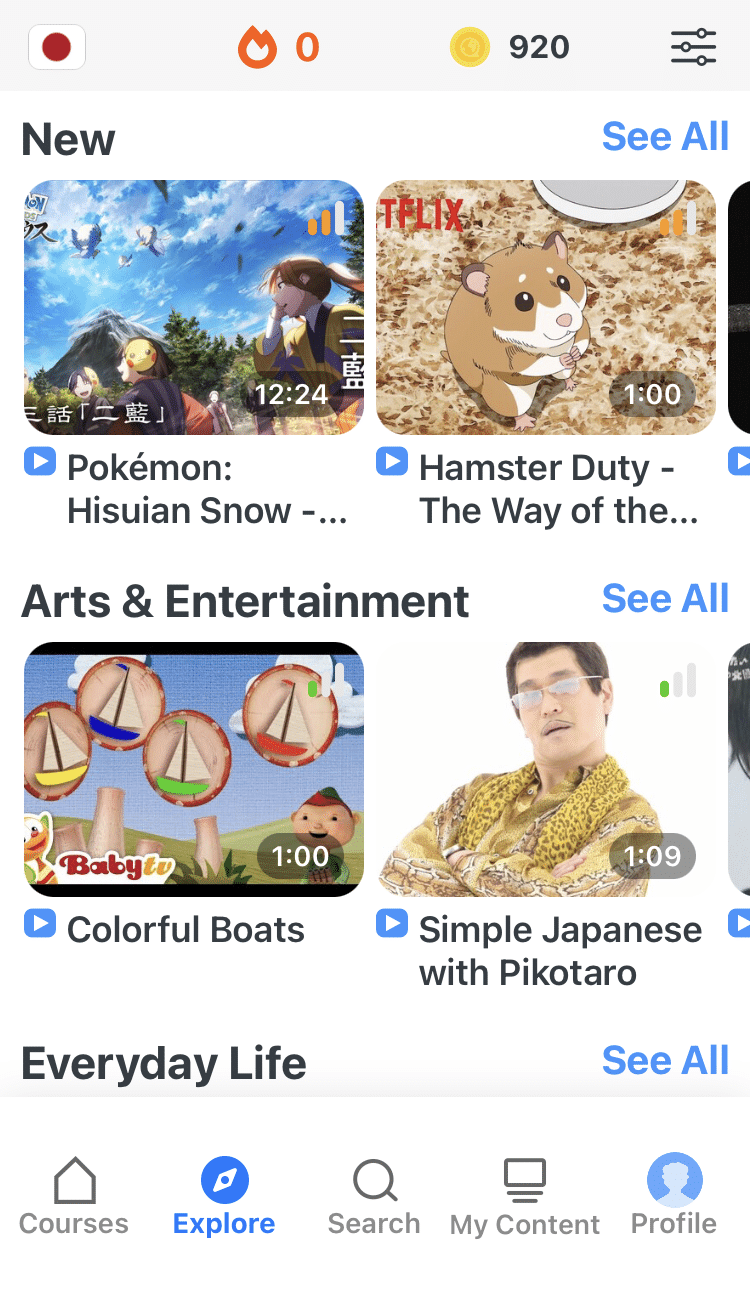

If you love learning Japanese with authentic materials, then I should also tell you more about FluentU.

FluentU naturally and gradually eases you into learning Japanese language and culture. You'll learn real Japanese as it's spoken in real life.

FluentU has a broad range of contemporary videos as you'll see below:

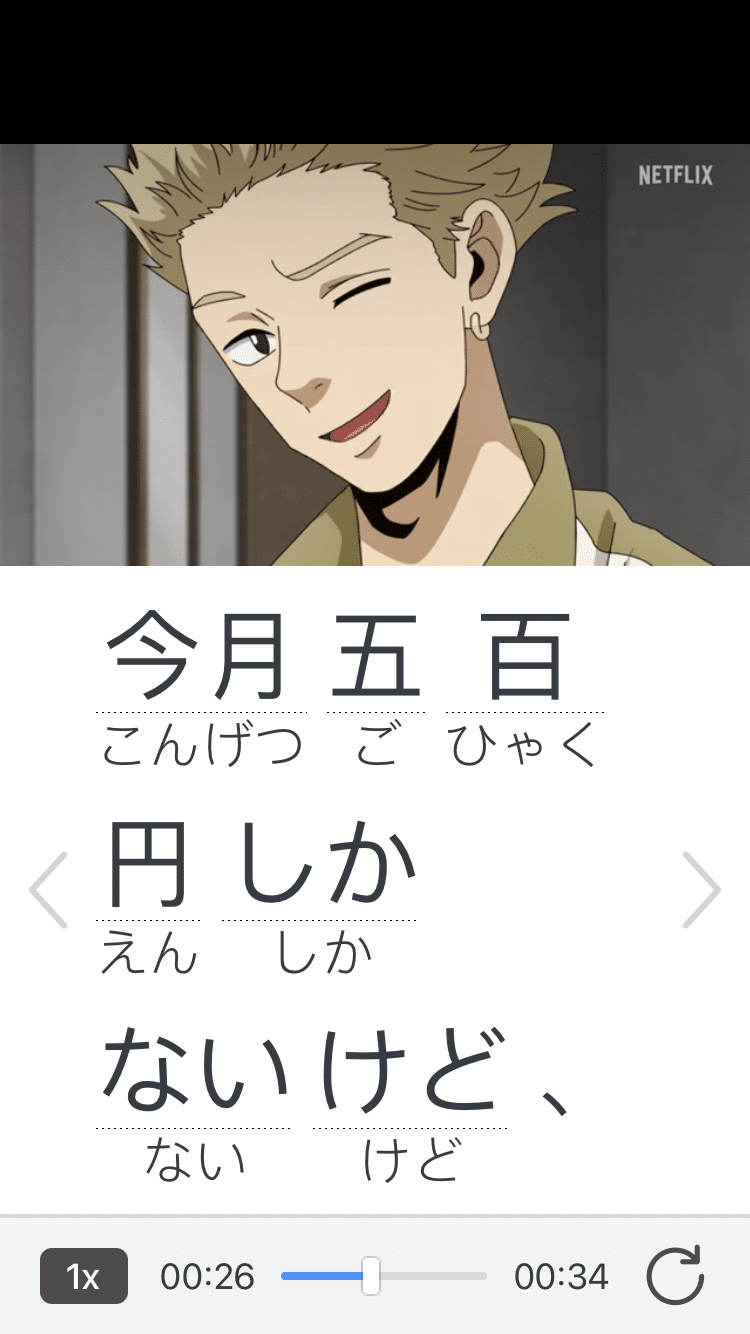

FluentU makes these native Japanese videos approachable through interactive transcripts. Tap on any word to look it up instantly.

All definitions have multiple examples, and they're written for Japanese learners like you. Tap to add words you'd like to review to a vocab list.

And FluentU has a learn mode which turns every video into a language learning lesson. You can always swipe left or right to see more examples.

The best part? FluentU keeps track of your vocabulary, and gives you extra practice with difficult words. It'll even remind you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. You'll have a 100% personalized experience.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)