Haben and Sein Conjugations

Just like in English, the German words haben (“to have”) and sein (“to be”) are arguably the most common verbs and are crucial to comprehending and mastering the German language.

Keep haben and sein in mind as we work through what we use these two verbs for and some common conjugations of each to memorize for daily use.

By the end of this post, you’ll be able to express your state of being, as well as what you have, with ease!

Contents

- What Are the Forms of Haben and Sein?

- Choosing Between Haben and Sein

- How to Conjugate Haben and Sein

- And One More Thing...

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

What Are the Forms of Haben and Sein?

When we say haben , we’re using the infinitive of the verb. In English, this would be “to have.”

But if we are to use this verb in a sentence, we’ll need to conjugate it!

Conjugation is how the verb changes depending on who you are talking about. We do this in English too: Look at how “to have” changes between the sentences “I have” and “she has.”

Now haben is rather irregular, but it does still follow the same patterns with its endings:

| Subject | Verb ending | Haben conjugation |

|---|---|---|

| ich (I) | -e | habe |

| du (you [informal, singular]) | -(e)st | hast |

| er/sie/es (he/she/it) | -t | hat |

| wir (we) | -en | haben |

| ihr (you [informal, plural]) | -t | habt |

| Sie/sie (You [formal]/they) | -en | haben |

That being said, as you can see, there are some identifiable patterns to keep in mind. The wir and Sie/sie forms always use the infinitive ending (-en), so conjugation for these subjects is simple.

In the case of haben, the du and the er/sie/es forms lose the b.

haben → du hast, er/sie/es hat

Sein is a verb all its own, much like the English “to be.” Forms of sein are usually memorized by German learners and kept fresh in the mind with frequent use.

Choosing Between Haben and Sein

As a general rule of thumb, expressing or translating instances of “to be” correlates to sein in German.

Similarly, using haben for the English “to have” is most often appropriate.

There are, as goes for any language, exceptions to this rule. You might consider these exceptions to be idioms of a certain sort, as they’re most often characterized by the German way to express a certain thing.

Exceptions often come about when describing certain needs or emotions. For example, being hungry or thirsty. Whilst you just literally translate from English and use the same adjectives, ich bin hungrig or ich bin durstig , it’s more idiomatic to say ich habe Hunger or ich habe Durst , literally “I have hunger/I have thirst.”

You also use haben instead of sein when expressing, “I am scared” as Ich habe Angst .

Here are some more common expressions that use haben in German:

| German | English | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Glück haben | To be lucky (lit. "to have luck") | Sie haben Glück, so viele Parks in ihrer Stadt zu haben. (They are lucky to have so many parks in their city.) |

| Recht haben | To be right (lit. "to have right") | Ich denke, wir haben Recht! (I think we are right!) |

| Unrecht haben | To be wrong (lit. "to have wrong") | Es tut mir leid, aber du hast Unrecht. (I am sorry, but you are wrong.) |

| Eile haben | To be in a rush (lit. "to have rush/hurry") | Ich habe es eilig, weil ich spät aufgewacht bin. (I am in a rush because I woke up late.) |

| Heimweh haben | To be homesick (lit. "to have homesickness") | Der Austauschstudent hat Heimweh. (The exchange student is homesick.) |

Most often these exceptions work in this way, where you are “having” something, rather than “being” something, but as you learn German, you’ll become familiar with these outliers.

How to Conjugate Haben and Sein

Ready to take a look at haben and sein conjugations in more detail? Let’s get started!

Present Tense

Since most of our everyday speech is spoken in the present tense, you’ll see haben and sein most often in the following forms.

Remember that we discussed the formulation of the present tense conjugation for haben—and regular verbs—previously. We begin with the infinitive, drop the -en ending and use the appropriate endings based on our subject:

| German | English |

|---|---|

| ich habe | I have |

| du hast | You have (informal, singular) |

| er/sie/es hat | He/she/it has |

| wir haben | We have |

| ihr habt | You have (informal, plural) |

| Sie/sie haben | You have (formal)/They have |

The conjugations for sein are as follows. Again, these forms should be memorized since they’re irregular.

| German | English |

|---|---|

| ich bin | I am |

| du bist | You are (informal, singular) |

| er/sie/es ist | He/she/it is |

| wir sind | We are |

| ihr seid | You are (informal, plural) |

| Sie/sie sind | You are (formal)/They are |

Let’s put what we’ve learned into action. I want to say, “I have a cat” in German. Since we are using “have,” we’ll choose haben. Our subject is ich, so the corresponding conjugation is habe. Last but not least comes eine Katze (a cat) to form:

What if you want to say how old you are? For this instance, we use sein, and since our subject is the same (I), we use ich bin. If you’re 13 years old, you would use dreizehn Jahre alt. Putting it all together, we have:

Simple Past Tense

After you’ve familiarized yourself with the present tense, take a look back in time to focus on the past. The simple past tense is a quick way to describe the past, much like the perfect past tense, which we’ll discuss next.

Haben and sein become hatten and waren in the simple past tense. Hatten follows the same rules of regular verbs:

| German | English |

|---|---|

| ich hatte | I had |

| du hattest | You had (informal, singular) |

| er/sie/es hatte | He/she/it had |

| wir hatten | We had |

| ihr hattet | You had (informal, plural) |

| Sie/sie hatten | You had (formal)/They had |

Just like its present tense form, the past tense of sein is completely different from the infinitive:

| German | English |

|---|---|

| ich war | I was |

| du warst | You were (informal, singular) |

| er/sie/es war | He/she/it was |

| wir waren | We were |

| ihr wart | You were (informal, plural) |

| Sie/sie waren | You were (formal)/They were |

Wait a minute, you say! How can the ich and the er/sie/es form be the same? Isn’t that why haben has different forms in the present tense?

The trick of the simple past is that the ich and er/sie/es forms are identical, no matter if the verb is regular or irregular. It just means you have one less verb form to memorize!

If you want to say, “We had an important meeting yesterday,” choose the wir, past tense form of haben and you get:

Wir hatten gestern eine wichtige Besprechung.

Or to say, “She was at home today,” choose the sie past tense form of sein and you get:

Perfect Past Tense

In many ways, the simple past and the perfect past tense do the same job.

The difference comes in how they are used and constructed. The perfect past tense is sometimes referred to as the “conversational” past tense, as this is what you tend to use more when speaking, whereas the simple past tense is better suited for written or formal contexts.

The perfect past is also constructed in a different way to its “simple” sibling. For the perfect past tense, you need two verbs: an auxiliary (helper) verb and a past participle.

Depending on the context, you use haben or sein as the helper verb, conjugated in the present tense, with the past participle of the main verb occurring at the end of the sentence.

Here’s what the conjugations for haben look like:

| German | English |

|---|---|

| ich habe gehabt | I had |

| du hast gehabt | You had (informal, singular) |

| er/sie/es hat gehabt | He/she/it had |

| wir haben gehabt | We had |

| ihr habt gehabt | You had (informal, plural) |

| Sie/sie haben gehabt | You had (formal)/They had |

Sein works the same way:

| German | English |

|---|---|

| ich bin gewesen | I was |

| du bist gewesen | You were (informal, singular) |

| er/sie/es ist gewesen | He/she/it was |

| wir sind gewesen | We were |

| ihr seid gewesen | You were (informal, plural) |

| Sie/sie sind gewesen | You were (formal)/They were |

So logic prevails and haben takes haben and sein takes sein as their auxiliary verbs. But how do you know whether to use haben or sein when it comes to other verbs?

Whilst there are several exceptions, a general rule of thumb is to always use haben, except for verbs that describe movement or a change of state. In this case, you want to use sein.

Check out these examples:

Ich habe ein Auto gekauft. (I bought a car.)

Kaufen (to buy) doesn’t describe movement or a change of state, so here we use haben.

Ich bin ins Kino gegangen. (I went to the movies.)

Gehen (to go), which has a past participle of gegangen, clearly describes movement, so here we use sein.

There are some examples that don’t follow these rules, like sich verwandeln (to transform) taking haben, or bleiben (to stay) taking sein. But the movement/change of state rule is generally good enough to get you by while you’re learning!

Pluperfect Tense

We’re going even further into the past now with this tense. When talking about something in the past tense, how do you talk about something that happened before that? You use the pluperfect!

This exists in English too, and we often use it when telling stories: “I had just woken up, when I heard a knock at my door…”

To form this in German, it’s actually really easy! We basically do exactly as we would do in the perfect past tense, but instead of using one of our auxiliaries haben or sein in the present tense, we just pop them in the simple past. We then add the past participle on at the end of the clause as normal.

So if you have a verb like sehen (to see) that takes haben, instead of saying Ich habe den Film schon gesehen (I have already seen the movie), it becomes— Ich hatte den Film schon gesehen. (I had already seen the movie.)

And the same rules apply as with the perfect, where some verbs, mostly those describing a movement or change of state, take sein. So here, instead of Ich bin krank gewesen (I have been ill) you say— Ich war krank gewesen. (I had been ill.)

Here’s some examples in context:

Ich konnte die Tür nicht öffnen, weil ich vorhin meinen Schlüssel verloren hatte. (I couldn’t open the door because I had lost my key earlier.)

Nachdem ich aufgewacht war, erwartete mich eine große Überraschung. (A big surprise was waiting for me after I had woken up.)

Wir waren spät angekommen und wollten direkt ins Bett gehen. (We had arrived late and wanted to go straight to bed.)

Future Tense

As you might already guess, the future tense describes an event that will happen, officially called the Futur I.

Luckily, this is formed almost exactly the same as it is in English, with an auxiliary and the infinitive.

The German verb that functions the same as “will” in this context is werden and is conjugated in the following way:

| German | English |

|---|---|

| ich werde | I will |

| du wirst | You will (informal, singular) |

| er/sie/es wird | He/she/it will |

| wir werden | We will |

| ihr werdet | You will (informal, plural) |

| Sie/sie werden | You will (formal)/They will |

So to say you’ll have something or be something, you just conjugate werden and then send either haben or sein to the end. Easy!

Let’s try saying: “You will be invincible.” Try this German line using sein:

What if you want to manifest getting on the property ladder and say, “I will have a huge house”? Use haben and say:

Ich werde ein riesiges Haus haben.

Future Perfect Tense

You may have been wondering—if there’s a Futur I, does that mean there’s a sequel in the works? Well, you’re right, as next up we’ve got the Futur II!

Luckily, this is also a tense we have a near identical equivalent of in English: You use the future perfect to talk about actions you believe you will have completed at some point in the future. For example: “By the end of this article, I will have learned all the conjugations of haben and sein.”

You form this by just squishing together the components for the perfect tense and the future. So we need werden conjugated to the subject, an auxiliary verb of either haben or sein and then a past participle. Because werden sends the second verb to the end, the auxiliary of haben or sein needs to go to the end of the clause.

Here are a couple of examples:

Ich werde meine Abschlussarbeit abgegeben haben. (I will have handed in my final thesis.)

Hoffentlich wird sie bis dahin eingeschlafen sein. (Hopefully, she will have fallen asleep by then.)

Conditional Tense

What if you want to say, “I would be” or “I would have”?

We call this the conditional tense and form it using wären and hätten which are forms of sein and haben respectively.

Haben is conjugated in the present tense via regular verb rules:

| German | English |

|---|---|

| ich hätte | I would have |

| du hättest | You would have (informal, singular) |

| er/sie/es hättet | He/she/it would have |

| wir hätten | We would have |

| ihr hättet | You would have (informal, plural) |

| Sie/sie hätten | You would have (formal)/They would have |

The same rules apply to wären:

| German | English |

|---|---|

| ich wäre | I would be |

| du wärst | You would be (informal, singular) |

| er/sie/es wäre | He/she/it would be |

| wir wären | We would be |

| ihr wärt | You would be (informal, plural) |

| Sie/sie wären | You would be (formal)/They would be |

“I would be thankful” translates to Ich wäre dankbar and “He would have a problem with that” becomes Er hätte ein Problem damit.

If you’re a grammar nerd, this is in fact the second form of the conditional tense, known as Konjunktiv II.

If that’s all seeming a bit too tricky for now, you can forgo the use of this proper form of the subjunctive, and form a conditional sentence by using würden (very similar to “would” in English). You then just insert haben or sein at the end of the sentence in the infinitive:

| German | English |

|---|---|

| ich würde | I would |

| du würdest | You would (informal, singular) |

| er/sie/es würde | He/she/it would |

| wir würden | We would |

| ihr würdet | You would (informal, plural) |

| Sie/sie würden | You would (formal)/They would |

The two examples above become:

and

Er würde ein Problem damit haben.

It’s more common to hear the aforementioned.

Bonus: Conditional Past Tense

The subjunctive forms of haben and sein—hätte and wäre—are also used in the conditional past tense with a past participle to express what someone “would have done” if it weren’t for something else. In German, this is called Konjunktiv II (Subjunctive II).

Just like with the normal perfect past tense, you need to choose between haben or sein depending on what verb you are using. The same rules apply here, so generally most verbs take haben, or in this case, hätte. Whereas those describing movement or a change of state take sein, or here, wäre.

Here are some examples of these verbs in use:

Wenn ich fleißiger gelernt hätte, hätte ich die Prüfung bestanden. (If I had studied harder, I would have passed the exam.)

Wenn wir es gewusst hätten, hätten wir dir geholfen! (If we had known, we would have helped you!)

Es wäre einfacher gewesen, mit dem Zug zu fahren. (It would have been easier to travel by train.)

There’s a unique grammar rule that often comes into play with sentences like these. Usually, you are used to sending the auxiliary verb, either haben or sein, to the end of the clause.

But if you have two verbs already, for example, in a modal construction like Ich muss arbeiten (I need to work), then your haben or sein actually get skipped straight to the front of your verb queue. Talk about V.I.P.! (Very Important Participle…)

Wenn ich nicht hätte arbeiten müssen, wäre ich zur Party gekommen. (If I did not have to work, I would have gone to the party.)

Reported Speech

If the aforementioned forms are the Konjunktiv II, what happened to the first one? Well spotted, because we’re not quite done with the subjunctive yet…

The Konjunktiv I is actually a form used for reported speech, so when reporting what someone else has said, and is used to make it clear that the statement does not come from the person saying it, but rather from someone else. In English, we often just use phrases like “apparently,” “according to” or use direct quotes.

It’s most often used in journalism, reporting or legal documents, so it’s not a form you need to learn for casual conversation. But being aware of it is certainly worth it to stop you getting bamboozled when tuning in to German news.

Haben is a good verb to start with, as it shows the main way this tense differs from the usual present tense:

| German | English |

|---|---|

| ich habe | I (supposedly) have |

| du hast | You (supposedly) have |

| er/sie/es habe | He/she/it (supposedly) has |

| wir haben | We (supposedly) have |

| ihr habt | You (supposedly) have |

| Sie/sie haben | You (supposedly) have [formal]/They (supposedly) have |

That’s right, the er/sie/es form ends on -e not -t! Aside from sein, this is the only way it differs from the standard present tense. So if you need to conjugate the verb in the third person plural, for example, you will instead rely on the Konjunktiv II form.

Sein is the only verb that is completely different in this form:

| German | English |

|---|---|

| ich sei | I (supposedly) am |

| du seiest | You (supposedly) are |

| er/sie/es sei | He/she/it (supposedly) is |

| wir seien | We (supposedly) are |

| ihr seiet | You (supposedly) are |

| Sie/sie seien | You (supposedly) are [formal]/They (supposedly) are |

Here’s some examples of it in use:

Die Regierung behauptet, sie habe die Situation unter Kontrolle. (The government claims they have the situation under control.)

Der Abgeordnete sagt, das Gesetz sei nicht sinnvoll. (The lawmaker says that the measure does not make sense.)

And now you know haben and sein, you can also use this form in the past tense. Woohoo!

Der Wissenschaftler betont, er habe nichts Neues entdeckt. (The scientist emphasizes that he has not discovered anything new.)

Giving Orders with the Imperative Form

Attention! Time to turn said attention to the matter of giving orders like “be quiet,” “be patient” or “don’t be scared!”

We can form lots of useful instructions with haben or sein. And as giving instructions requires another person you’re talking to in the mix, we only need to worry about the conjugations for du, wir, ihr and Sie. The wir form is similar to saying “let’s do…” in English.

Haben is conjugated in the standard way for infinitives. Pay close attention to the wir and Sie forms, where we still need to include the respective pronouns:

| Pronoun | German | English |

|---|---|---|

| du | hab | have (singular, informal) |

| wir | haben wir | let's have |

| ihr | habt | have (plural, informal) |

| Sie | haben Sie | have (formal) |

Sein is unique in that it conjugates completely differently in the imperative. But luckily, you’ve already seen this strange sei conjugation above for the indirect speech, or Konjunktiv I form. So nothing brand new to learn!

| Pronoun | German | English |

|---|---|---|

| du | sei | be (singular, informal) |

| wir | seien wir | let's be |

| ihr | seid | be (plural, informal) |

| Sie | seien Sie | be (formal) |

Here’s some examples of instructions using haben and sein in the imperative form.

Sei still! (Be quiet!)

Kinder, seid brav! (Children, be well-behaved!)

Seien wir doch ehrlich, sie kommt nicht! (Let’s be honest, she’s not coming!)

Hab keine Angst! (Don’t be scared!)

Bitte haben Sie etwas Geduld mit mir. (Please have patience with me.)

Now that you’ve seen all the haben and sein conjugations, it’s time to learn them!

One of the best ways to learn how to conjugate these two verbs is by immersing yourself in the language. It’ll take some input, but you’ll find that you’re slowly internalizing the structures and no longer need to think through how to change each verb to fit every situation.

Luckily, there’s no scarcity of resources across the internet. For example, you could check out the FluentU program.

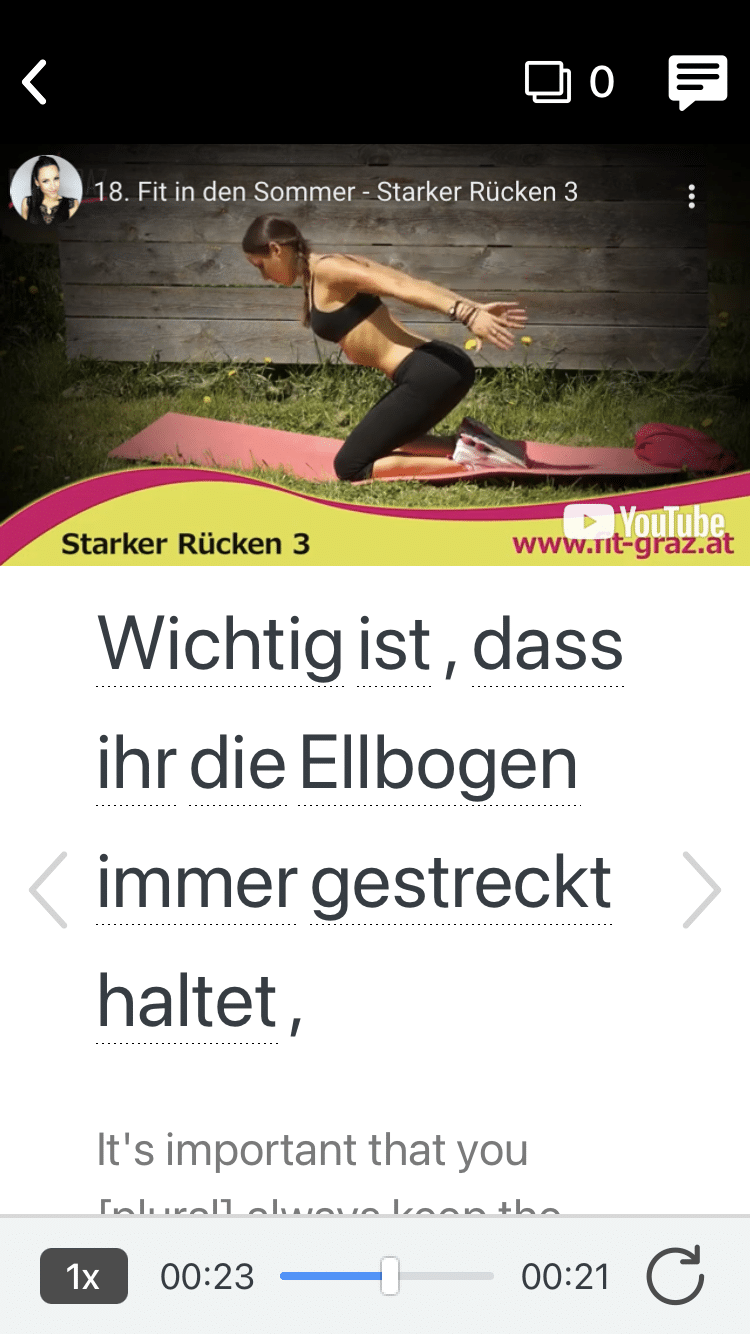

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

As with all things language, your skills will only improve if you continue to use the language.

Speak, read and write with haben and sein, and soon you’ll be on your way to understanding and mastering the German language!

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing...

Want to know the key to learning German effectively?

It's using the right content and tools, like FluentU has to offer! Browse hundreds of videos, take endless quizzes and master the German language faster than you've ever imagine!

Watching a fun video, but having trouble understanding it? FluentU brings native videos within reach with interactive subtitles.

You can tap on any word to look it up instantly. Every definition has examples that have been written to help you understand how the word is used. If you see an interesting word you don't know, you can add it to a vocabulary list.

And FluentU isn't just for watching videos. It's a complete platform for learning. It's designed to effectively teach you all the vocabulary from any video. Swipe left or right to see more examples of the word you're on.

The best part is that FluentU keeps track of the vocabulary that you're learning, and gives you extra practice with difficult words. It'll even remind you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)