15 Japanese Kanji Synonym Pairs + How to Learn Characters with Similar Meanings

One thing that nobody has ever said about kanji is that there are too few of them.

The jōyō kanji list, with its 2,136 characters, could have been made half as long and still pose a serious challenge for learners of Japanese.

So why does the list include so many characters that have identical kun-yomi readings and very similar meanings? Don’t we have enough to do without having to learn an endless string of apparent duplicates?

The thing is, those aren’t really duplicates at all.

The reason that many words can be written with several alternative characters is that kun-yomi (native Japanese) words tend to cover broad, general ideas, while kanji usually have narrow and specific meanings.

Each alternative character indicates a more or less distinct shade of meaning within the same word. It’s as if we wrote the English verb “hunt” with two different spellings—one standing for the literal sense of chasing and capturing an animal, and another for the figurative sense of actively trying to obtain something desirable such as a new job.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

The Origins of Japanese Kanji Synonyms

Kanji were originally used as independent words in ancient Chinese, and when they were imported to Japan they were already associated with their specific meanings.

What we now call kun-yomi isn’t an actual “reading” but simply a translation of those meanings into Japanese. Native words were used to describe what the characters meant—just like looking at the kanji 火 (kun-yomi: ひ and ほ; on-yomi: か) and saying “fire” in English instead of using the Chinese reading of huǒ.

The trouble is, native Japanese vocabulary was nowhere nearly as rich as the Chinese one. Many concepts that were expressed distinctly in Chinese using different words could only be mapped onto a single Japanese word that covered all of them simultaneously.

The Japanese, however, turned this problem on its head and took advantage of it to make their catch-all words much less ambiguous and confusing to read. Relying on the ability to express one word with many kanji, they used different characters to explicitly distinguish important meanings within the same word—meanings that could otherwise only be inferred from context.

This is how we got the one-to-many relationship between kun-yomi and kanji.

When Are These Japanese Synonyms Used?

Synonymous characters that share the same kun-yomi are called 同訓異義 (どうくんいぎ, “same reading, different definition”). Many common kun-yomi words have two, three or even more such characters associated with them, each one standing for a different shade of meaning.

There are cases where the distinction between characters is so subtle that few natives even know what it is, let alone bother to observe it in normal usage. But more often than not, it is necessary to have a good command of the proper meaning and usage of each kanji synonym if you’re going to write Japanese correctly and understand what you read.

To get you started in this wild but wonderful world of kanji synonyms, I’ll introduce you to 15 of the most common examples you’re likely to see in everyday language. To make things easier, all of these examples are pairs of jōyō characters—without getting into mammoth synonym groups that include multiple jōyō and non-jōyō characters such as おそれる (ten characters) or とる (six characters).

Each pair represents one kun-yomi word, but may also be related to other similar words that observe the same basic kanji distinction. For example, the adjective まるい is related to the verb まるめる, and using 丸 or 円 to write these results in the same nuance whether you’re writing the adjective or the verb.

So let’s start going over our 15 examples! After that, I’ll give you a few general tips on how to learn kanji synonyms effectively.

15 Sneaky Japanese Kanji Synonyms with Very Subtle Usage Differences

1. 有る vs. 在る

Hiragana: ある

Shared meaning: Being present.

有る: To be in the possession of someone. To be had. This is the Japanese equivalent of “have”, but the subject is the thing possessed rather than the person who possesses.

在る: To exist, to be in existence, generally in the world or specifically in some designated place.

Usage examples:

才能が有る (さいのう が ある)

To have a talent (for something)

アメリカに在る (あめりか に ある)

Located in America

2. 生まれる vs. 産まれる

Hiragana: うまれる

Shared meaning: Being born.

生まれる: Birth as a new beginning; the appearance of someone or something in the world.

産まれる: Birth as the biological phenomenon of emerging from the mother’s body.

Usage examples:

大阪で生まれた (おおさか で うまれた)

Born in Osaka

産まれる時間 (うまれる じかん)

The time of birth

3. 踊る vs. 躍る

Hiragana: おどる

Shared meaning: Moving energetically while lifting the feet off the ground.

踊る: To dance to music.

躍る: To leap, to jump forcefully.

Usage examples:

タンゴを踊る (たんご を おどる)

To dance the tango

胸が踊る (むね が おどる)

The heart leaps (with excitement).

4. 影 vs. 陰

Hiragana: かげ

Shared meaning: Being obscure, not directly lit.

影: Shadow, the dark shape created by a body that stands in the way of rays of light. Refers to that body’s shape as cast on a surface, or its silhouette when directly looked at.

陰: Shade, shadows, referring to a place hidden from direct light or the line of sight of observers. On top of its literal meaning, this word can also cover a range of related meanings such as “behind,” “under,” etc., in relation to something that acts as a shelter or obstruction.

Usage examples:

影が映る (かげがうつる)

To cast a shadow

木の陰で (きのかげで)

In the shade of a tree; under a tree

5. 乾く vs. 渇く

Hiragana: かわく

Shared meaning: Lack of water.

乾く: To become dry, to dry up, to be parched.

渇く: To become thirsty, to crave water. Also signifies the figurative sense of craving for something.

Usage examples:

乾いたシャツ (かわいた しゃつ)

A dry shirt (after doing the laundry)

喉が渇く (のど が かわく)

To be thirsty

6. 超える vs. 越える

Hiragana: こえる

Shared meaning: Going beyond a certain thing.

超える: To cross a certain point in time or space and move beyond it.

越える: To exceed, to surpass a certain scope, threshold, level, etc. To go above a certain point of reference.

Usage examples:

山を超える (やま を こえる)

To go over a mountain

気温が30度を越える (きおん が さんじゅうど を こえる)

The air temperature is above 30 degrees

7. 探す vs. 捜す (さがす)

Shared meaning: Attempting to find something or someone.

探す: To look for something you want to have or someone you want to reach. The emphasis is on making contact with the object and obtaining it.

捜す: To look for something or someone whose location is unknown. The emphasis is on discovering the whereabouts of the object.

Usage examples:

アルバイトを探す (あるばいと を さがす)

To look for a part-time job

落としたイヤリングを捜す (おとした いやりんぐ を さがす)

To look for a lost earring

8. 戦う vs. 闘う

Hiragana: たたかう

Shared meaning: Acting vigorously to defeat an opposing force.

戦う: To fight an adversary using force, skills, etc., in order to emerge victorious in a violent conflict or a contest.

闘う: To struggle, to battle against difficulties, hardships, limitations, etc. in order to overcome them.

Usage examples:

敵国と戦う (てきこく と たたかう)

To fight with an enemy nation

病気と闘う (びょうき と たたかう)

To battle an illness

9. 尊い vs. 貴い

Hiragana: とうとい / たっとい

Shared meaning: Being highly valued.

尊い: Noble, exalted. Often used for persons.

貴い: Valuable, precious. Often used for things.

Usage examples:

尊い身分 (とうとい みぶん)

High standing (in society)

貴い教訓 (とうとい きょうくん)

A valuable lesson

10. 始め vs. 初め

Hiragana: はじめ

Shared meaning: Beginning, start.

始め: The initial stage of something new. Has an active nuance that suggests the start of some deliberate action or process.

初め: The first part of something. Indicates a certain point on a tangible dimension in time or space.

Usage examples:

仕事の始め (しごと の はじめ)

The beginning of a job

冬の初め (ふゆ の はじめ)

The beginning of winter

11. 一人 vs. 独り

Hiragana: ひとり

Shared meaning: A single person.

一人: One person. The emphasis is on the simple number of people.

独り: Being alone, on one’s own, without interacting with other people. The emphasis is on the state of solitude.

Usage examples:

一人の女性 (ひとり の じょせい)

One woman

独りで歩く (ひとり で あるく)

Walking alone

12. 船 vs. 舟

Hiragana: ふね

Shared meaning: A vessel that travels on water.

船: A ship. Used for large vessels.

舟: A boat. Used for small vessels, often those made from light materials.

Usage examples:

船で行く (ふね で いく)

To travel by ship

舟を漕ぐ (ふね を こぐ)

To row a boat

13. 町 vs. 街

Hiragana: まち

Shared meaning: A densely built-up populated area.

町: An independent town within a county, or a neighborhood within a larger city.

街: A bustling street or quarter with many commercial establishments.

Usage examples:

町外れ (まち はずれ)

The outskirts of a town

街角 (まち かど)

A street corner

14. 丸い vs. 円い

Hiragana: まるい

Shared meaning: Roundedness.

丸い: Spherical, ball-shaped. Refers to a three-dimensional object.

円い: Round, circular. Refers to a two-dimensional shape.

Usage examples:

地球は丸い (ちきゅう は まるい)

The earth is round

円い窓 (まるい まど)

A round window

15. 柔らかい vs. 軟らかい

Hiragana: やわらかい

Shared meaning: Having low resistance to external force.

柔らかい: Flexible, supple, can be bent without being broken.

軟らかい: Soft, tender, can easily be reshaped.

Usage examples:

柔らかい毛布 (やわらかい もうふ)

Soft blanket

軟らかい粘土 (やわらかい ねんど)

Soft clay

How to Learn Your Japanese Kanji Synonyms

Your best guide to the differences between kanji synonyms is actual usage—the way that natural, native-written Japanese uses kanji in context.

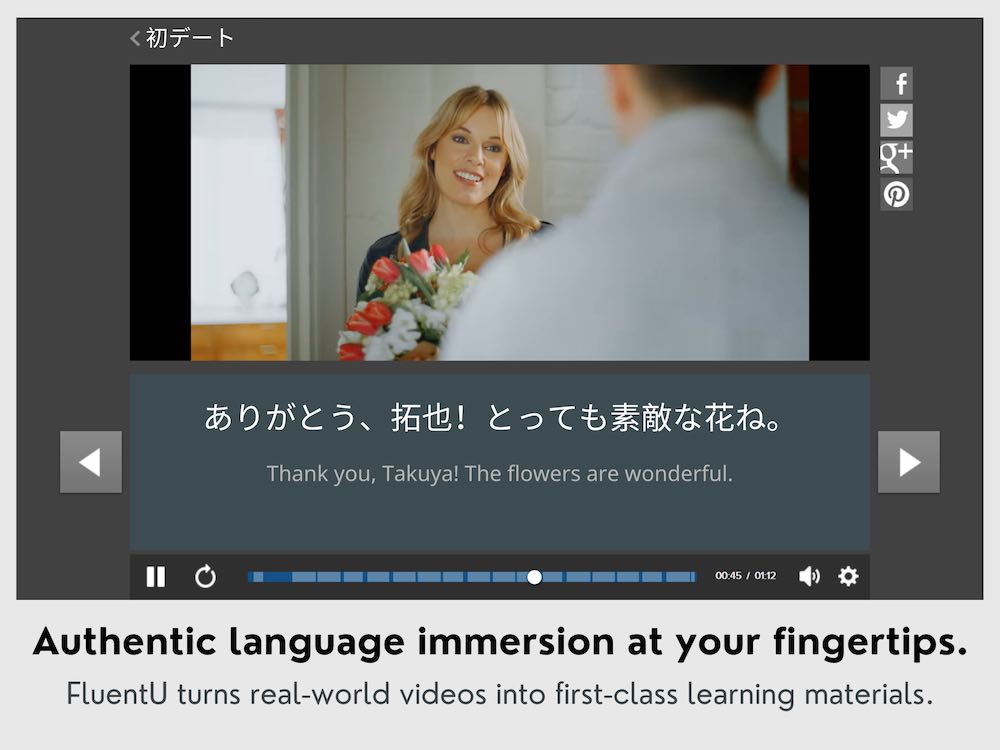

Pay close attention to how the same kun-yomi word is written using different characters in different cases; by routine exposure you will gradually absorb many distinctions without having to learn them consciously. Use a program like FluentU to further your understanding of how these words appear in context. The program uses a combination of videos and dual-language subtitles to help you understand every word you hear.

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Another thing that will help you is to look at how kanji are used in compound words. Characters are usually associated with the same shades of meaning whether they are used on their own or as elements in a compound, and regardless of their on-yomi or kun-yomi.

The third and most efficient thing to do is use specialized kanji synonym dictionaries. There are a few good ones online—I recommend those at Kanjipedia, Nihonjiten and Joyokanji.info. These three dictionaries are entirely in Japanese, but they are easy to navigate because they classify words by their sounds (written in hiragana).

The definitions are short and helpful, and also include example phrases that help you understand the actual usage of the characters. If you prefer printed dictionaries, there’s a variety to choose from—a good one to check out is Shizuka Shirakawa’s dictionary of kanji synonyms.

Well, that about covers everything you need to know about kanji synonyms and how to learn them.

Now that you’ve finished reading (よむ: 読む — not 詠む or 訓む) this article, you can go ahead and tackle those characters without letting them confuse you ever again!

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing...

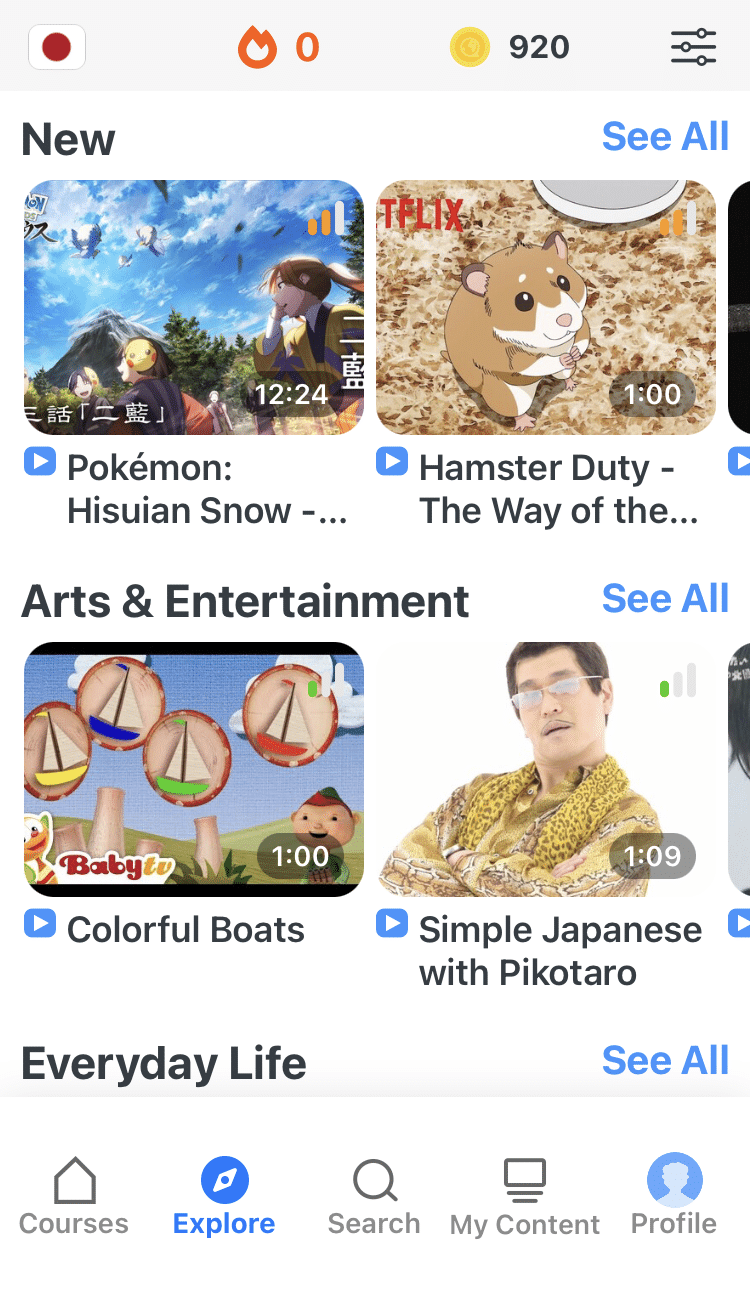

If you love learning Japanese with authentic materials, then I should also tell you more about FluentU.

FluentU naturally and gradually eases you into learning Japanese language and culture. You'll learn real Japanese as it's spoken in real life.

FluentU has a broad range of contemporary videos as you'll see below:

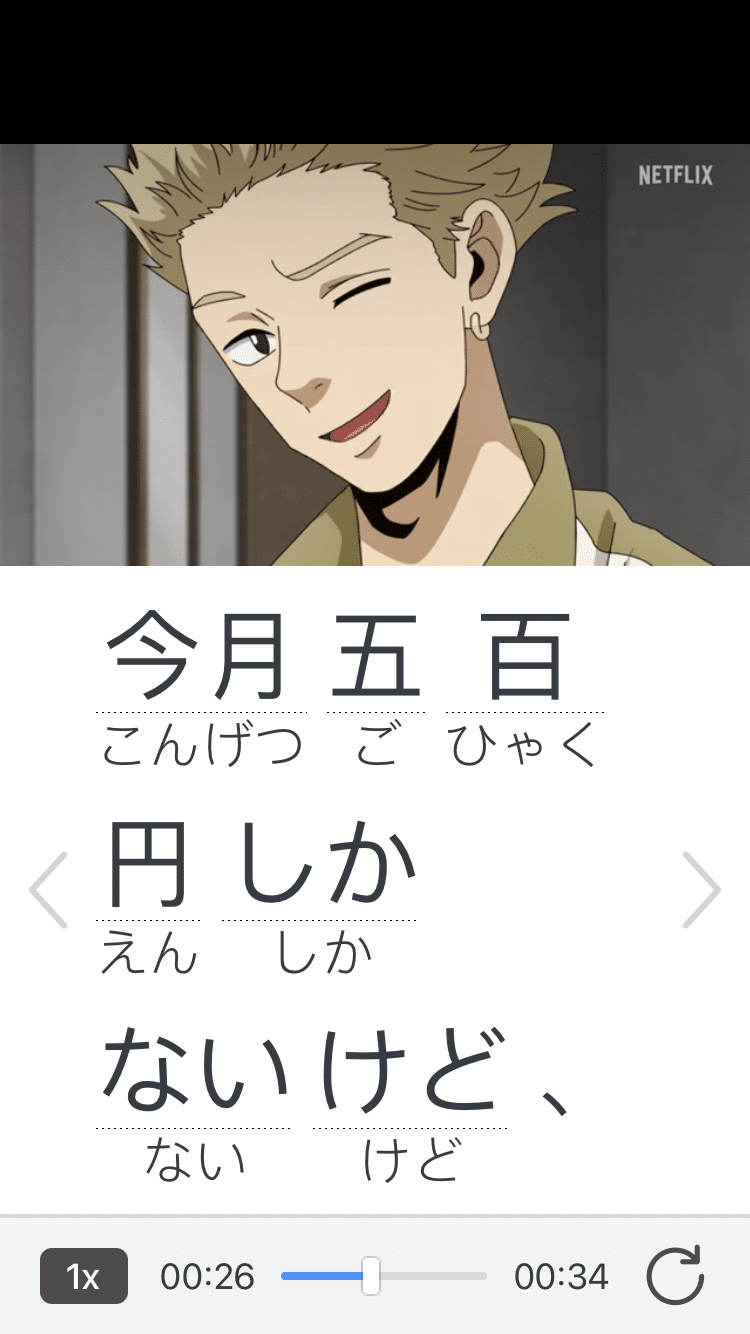

FluentU makes these native Japanese videos approachable through interactive transcripts. Tap on any word to look it up instantly.

All definitions have multiple examples, and they're written for Japanese learners like you. Tap to add words you'd like to review to a vocab list.

And FluentU has a learn mode which turns every video into a language learning lesson. You can always swipe left or right to see more examples.

The best part? FluentU keeps track of your vocabulary, and gives you extra practice with difficult words. It'll even remind you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. You'll have a 100% personalized experience.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)