7 Easy Tricks to Learn Conversational Japanese for Human Beings

I had made—yet another—social blunder.

I used a phrase that sounded way too formal and made it seem like I was putting distance between my friend and me.

Japanese learners might find themselves unwittingly making the same social gaffe, but this is no reason to shy away from a conversation!

By following the seven steps below, you can ease your way into conversation and save yourself some embarrassment by knowing how to talk, listen and respond like a human being.

Contents

- 1. Drop Pronouns or Subjects if It’s Clear Who or What You’re Referring To

- 2. Use Subjects if Talking About Them for the First Time or They’re Unclear

- 3. Use “Giving” Verbs

- 4. Interrupt Everyone

- 5. Keep it Casual with Conversational Sentence Patterns

- 6. Speak Like a Girl or Guy

- 7. Learn to Embrace Slang

- And One More Thing...

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

1. Drop Pronouns or Subjects if It’s Clear Who or What You’re Referring To

The English language loves pronouns. Sentences are filled with I, me, you, their and other similar forms of address.

Japanese is the opposite: oftentimes, pronouns are omitted altogether if the subject can be inferred. In other words, if the subject is clearly yourself or the person you’re talking to, it sounds more natural if you drop pronouns like “I” or “you.”

眠い! (ねむい!)

I’m sleepy!

(Literally: Sleepy!)

お腹が空いたよ!お昼にしようね。(おなかが すいたよ!おひるに しようね。)

I’m so hungry! Let’s have lunch.

(Literally: Stomach is empty! Do lunch, okay?)

お店に行くの?コーヒー買って来てくれない? (おみせに いくの?こーひー かってきてくれない?)

Are you going to the store? Can you get me a coffee?

(Literally: Store going to? Can please buy coffee for me?)

Note how there aren’t any pronouns like 私 (わたし or “I, me”) in the example above. When there’s never any subject to begin with, the speaker is usually talking about themselves or a group they’re included in.

Also, when a person makes a simple statement in Japanese without the rising question inflection at the end, you can automatically assume they’re probably talking about themselves.

2. Use Subjects if Talking About Them for the First Time or They’re Unclear

Although you should avoid overusing pronouns or subjects to sound more natural, there will be times when you might feel confused about who or what someone’s referring to.

This actually happens a lot in conversation, so feel free to ask for clarification:

A: 朝ご飯を食べましたか? (あさごはんをたべましたか?)

A: Did (you) eat breakfast?

B: 私ですか? (わたしですか?)

B: Me?

A: ええ。

A: Yeah.

A: 厳し過ぎるよ。 (きびしすぎるよ。)

A: He/She’s) too strict.

B: 先生のこと? (せんせいのこと?)

B: You mean (our) teacher?

A: ううん、校長。 (ううん、こうちょう。)

A: No, the principal.

If you leave off the subject when actually talking about someone else, it can sound like you’re talking about yourself. You may mean to say “you’re hungry” but actually end up saying “I’m hungry.”

When you’re making a simple statement, not a question, you should use a subject to clear up any confusion.

は and が

Another way to know what’s being talked about in a conversation is to keep track of は and が. The は or が post-participle in Japanese indicates the topic of the conversation. What everyone says afterward refers to it until someone mentions another topic with the は or が markers.

For example, if you have a bowl with a variety of fruits and you want to point out which one is the apple, you can pick up the fruit and say:

これは林檎です。 (これはりんごです。)

This is an apple.

The conversation will then follow with sentences along the lines of:

あ、(林檎は)赤過ぎる! (あ、(りんごは)あかすぎる!)

Ah, (the apple is) so red!

As you can see, there’s no need to mention the subject (the apple) since it’s already clearly the topic of conversation. If the subject changes, you’ll have to use は or が again.

そして、これは桃です。 (そして、これはももです。)

Likewise, this one is a peach.

3. Use “Giving” Verbs

Luckily for us English speakers, who suffer from an unreasonable insistence that people actually mention the things and people they’re talking about, there are grammatical markers that can be used to indicate the subject without saying it directly. These are “giving verbs”—verbs you can add to the end of a sentence to indicate that something is being given.

あげる

This means “to give,” but it can be helpful when determining the subject and the direction of speech. あげる indicates giving something away from the speaker to someone else.

If you give someone a present, this is the form you would use. In other words, when you attach あげる to a verb, it means you—the speaker—are doing it. It serves to add an invisible subject to the sentence. In effect, you’re saying “I.”

お金をあげる。 (おかねをあげる。)

I’ll give (someone) money.

プレゼントをあげました。 (ぷれせんとをあげました。)

I gave (someone) a present.

When you attach あげる to the end of a verb, it means not giving something to someone, but doing something for someone. Remember that the verb you attach it to will be conjugated in the て form.

電話してあげる。 (でんわしてあげる。)

I’ll call you.

次のビールを奢ってあげる。 (つぎのびーるをおごってあげる。)

I’ll buy you the next beer.

くれる

This is another commonly used “giving” verb that indicates the opposite direction from あげる. When you use くれる, it means someone is giving something to you, the speaker.

For example:

おもちゃをくれた。

(Someone) gave me a toy.

Similar to あげる, you can attach くれる to the -て form of a verb, and it means that somebody is doing something for you:

助けてくれてありがとう。 (たすけてくれてありがとう。)

Thank you for helping me.

This makes the other person the subject of the sentence. You’re the receiver of the action. Japanese speakers use these two verbs, あげる and くれる, at the end of sentences to indicate who is doing what for whom.

明日、東京スカイツリーに連れて行ってくれる。(あした、とうきょうすかいつりーにつれていってくれる。)

Tomorrow, (he’s/she’s/you’re/they’re) taking me to Tokyo Sky Tree.

貰う (もらう)

Like くれる, this is something being given towards the speaker. It has the nuance of having something done for you.

(私は)彼女にプレゼントをもらいました。 ((わたしは)かのじょにぷれぜんとをもらいました。)

(I) received a gift from her.

(Literally: I from her present received.)

As you can see from the literal translation, the structure for a sentence that uses もらう seems a bit complicated on the surface. However, it still follows the “subject + object + verb” structure: 彼女 (かのじょ or “her”) is the subject, プレゼント (ぷれぜんと or “present”) is the object and もらいました (もらいました or past form of もらう) is the verb.

So, if it’s understood that you’re the receiver, you can also drop 私は (わたしは) and translate the sentence as “She gave me a present.”

Also like the other giving verbs, もらう has a -て form. When you say – てもらう , it means you’re getting someone to do something for you.

お姉さんに来てもらう。 (おねーさんにきてもらう。)

(I will) get my (older) sister to come.

頂く (いただく)

いただく is essentially the more polite version ofくれる and もらう. This is used often in 敬語 (けいご) , the super-polite register of Japanese used for customer service or other formal situations.

ご住所をいただけますか? (ごじゅうしょをいただけますか?)

May I please have your address?

やる

This is used to indicate giving away from the speaker like あげる, but is giving much further downward. It’s used for children, people of a lower social position and animals.

(私は)猫に餌をやります。 ((わたしは)ねこにえさをやります。)

The cat received food (from me).

Again, in Japanese, it’s best to use subjects sparingly. Try to only use subjects when absolutely necessary. Use voice inflection, giving verbs and other devices to suggest who you’re talking about without actually referring to them directly.

If you want to learn more about useful Japanese verbs, you’ll love this post!

4. Interrupt Everyone

Another way to sound more natural in a conversation is to forget what you’ve been taught about how rude interrupting someone can be.

Interjecting an “Uh-huh” or gasping “No way!” ensures that you’re appearing attentive and interested in what someone has to say—even if they’re recapping that episode of Sailor Moon. Word-for-word. Again.

A typical conversation might go like:

A: イタリアンレストランで食事をしてから。 (いたりあんれすとらんでしょくじをしてから。)

A: We had dinner at an Italian restaurant.

B: うん。

B: Uh-huh.

A: 映画を見たの。いい人だから。 (えいがをみたの。いいひとだから。)

A: Then, we watched a movie. He’s a nice guy.

B: うん。

B: Uh-huh.

A: 日曜日にコーヒーでも飲みに行かないって誘ったの。 (にちようびに こーひーでも のみにいかないって さそったの。)

A: So I invited him for coffee on Sunday.

B: いいね。

B: Sounds great.

You get the point.

The “art of interruption” is called 相槌 (あいづち – giving responses). When you don’t use aizuchi while conversing, the other party will think you’re disinterested in what they have to say.

If you’re constantly being asked, “Are you listening to me?” in a conversation (despite your polite nodding and eye contact), make sure you give aizuchi a try. Mastering aizuchi will guarantee you have a smoother, more fluent-sounding conversation!

Here are some more quick, aizuchi-like interjections you can use.

いいね

On Facebook, いいね is used to say, “like!” Depending on your tone, pronunciation and the situation, いいね can have multiple connotations.

If you say it with enthusiasm and cheer, いいね sounds like, “That’s great!” If you were to sigh いいね instead, the meaning would sound more like, “It must be great…”

A: 彼が「また、電話してもいい?」って言ったの。 (かれが「また、でんわしてもいい?」っていったの。)

A: He said, “Can I call you again?”

B: いいね!

B: That’s great!

A: さとみちゃんは私の携帯を借りておきながら、家に忘れて来ちゃったのよ!おまけに… (さとみちゃんは わたしのけいたいをかりておきながら、いえにわすれてきちゃったのよ!おまけに…)

A: Satomi borrowed my cell phone and then left it at home! On top of that…

B: いいねぇ…

B: That’s nice…

A: 彼女、また海外に行ってるの?この間ヨーロッパへ行ったばかりじゃない。(かのじょ、またかいがいに いってるの?このあいだ よーろっぱへ いったばかりじゃない。)

A: She’s traveling overseas again? She just got back from Europe, didn’t she?

B: うん。いいねぇ…

B: Yeah. It must be nice (to be her).

でしょう and だよね

でしょう and だよね are ways to show agreement. This sounds like “I know, right?” or “Isn’t it?” A more masculine form of でしょう is だろう .

A: 映画は本当に感動的だった。 (えいがは ほんとうに かんどうてきだった。)

A: That film was really moving.

B: でしょう!私もそう思う。 (でしょう!わたしも そうおもう。)

B: Wasn’t it? I think so too!)

A: これはなかなかいい曲だよね。 (これは なかなか いいきょくだよね。)

A: This is a pretty good song, isn’t it?

B: だよね!

B: Heck yeah, it is!

あのね

あのね is おね way to start off a sentence. It’s similar to the English phrase, “You know.” Depending on your tone, あのね could serve as a small reminder or afterthought: “You know, now that I think about it, he was kind of rude.” Or if you’re getting angry, “You know — you’re way too ungrateful!”

あのね、ゆうきさんって かわいくない?

Say, don’t you think Yuuki is cute?

あのねぇ、結構大変だよ。 (あのねぇ、けっこう たいへんだよ。)

I’m telling you, it’s not that easy.

あのね、このケーキ試してみて。 (あのね、このけーき ためしてみて。)

Hey, try this cake.

あのね…金のアイフォンを買いたかったんだけどね... (あのね…きんのあいふぉんをかいたかったんだけどね...)

You know… I wanted to buy the gold iPhone…

気の毒 (きのどく)

気の毒 (きのどく) means “that’s a pity.”

Just like in English, this phrase can have different connotations depending on the tone you use. “What a pity,” “That’s too bad” and “What a shame” can all sound empathetic with a sincere tone in English, but can also be used sarcastically or with little sympathy—just like 気の毒 in Japanese.

気の毒ですね。 (きのどくですね。)

That’s a pity.

それは本当に気の毒ですよ。 (それはほんとうに きのどくですよ。)

I’m really sorry to hear that.

You can also use 気の毒 in an informal context as a way to say, “Too bad,” or “Tough luck.”

A: 携帯がトイレに落ちた! (けいたいが といれに おちた!)

A: My phone fell into the toilet!

B: はっ!お気の毒にね! (はっ!おきのどくにね!)

B: Ha! Sucks to be you!

信じられない (しんじられない)

信じられない (しんじられない or “Unbelievable!”) is a way to express that something is beyond belief or comprehension. You can use it to express your astonishment like exclaiming, “Oh my gosh!” or even say something is too unbelievable to be true.

そんなの信じられない! (そんなの しんじられない!)

No way / Get out!

しん君から今聞いたこと、信じられないんだけど! (しんくんから いま きいたこと、しんじられないんだけど!)

You won’t believe what Shin just told me!

信じられないよ!君は私にダイエットしろって言ったのに、それが今じゃ自分はガンガン食べるってわけか! (しんじられないよ!きみはわたしに だいえっとしろっていったのに、それがいまじゃ じぶんは がんがん たべるってわけか!)

I can’t believe you! You told me to diet, and now you’re the one pigging out?

Use these interjections and your speech with automatically sound smoother and more natural in conversation.

5. Keep it Casual with Conversational Sentence Patterns

So far, we’ve covered what not to do in a conversation (overuse pronouns and be a passive listener). Now it’s time to stop talking like a walking textbook and use real Japanese sentences and expressions.

Use the Backwards Sentence

A lot of Japanese textbooks will introduce their readers to the basic sentence pattern of “subject + object + verb” to construct sentences like 私はコーヒーを飲みました。 (わたしはこーひーをのみました。 – “I drank coffee”).

This kind of structure is very useful and still exists in conversational Japanese, but it’s used less outside of formal contexts. Many conversational sentences will seem “backwards” when compared to the “subject + object + verb” structure, so instead of これは何ですか? (これはなんですか? – “(literally) This is what?”), you’ll probably hear a friend say 何これ? (なにこれ? – “What’s this?”)

There are two really convenient situations where this particular sentence structure is used:

1. To clarify a sentence, or add something as an afterthought (which is very helpful when subjects and pronouns are dropped):

行ったこと [が] ありますか?パリに。 (いったこと [が] ありますか?ぱりに。)

Have you been before? To Paris.

2. To combine two sentences:

それは何? (それはなに? – “That is what?”)becomes 何それ? (なにそれ? – “What’s that?”).

Replace Words with Onomatopoeia

If you take away anything from this post, let it be onomatopoeia! Japanese onomatopoeia are a language learner’s secret weapon to sounding like a native speaker in a conversation.

Onomatopoeia are words used to represent sounds (the onomatopoeia of a bird chirping is tweet tweet). Not only is onomatopoeia used to replace adjectives and emphasis verbs in daily conversation, but it’s super easy to remember.

Even if you don’t use it, you should know some common onomatopoeia like ぺこぺこ (the sound of your stomach growling), わくわく (the sound of being excited) and ニコニコ (にこにこ or the imagined sound of someone smiling broadly).

A friend or family member is likely to say お腹がぺこぺこ (おなかがぺこぺこ or “My stomach’s growling”) once in a while instead of お腹が空いた ( おなかがすいた or “I’m hungry”).

Omit Sounds

In every language, we tend to slur or shorten sounds in conversation. In Japanese, the “r” sound (ら、り、る、れ、ろ)often gets reduced to the ん sound. You’ve probably already heard this in dramas, movies and even podcasts.

An example of this is when 分からない (わからない or “I don’t know”) changes into 分かんない (わかんない):

何のことだかさっぱりわかんないよ。 (なんのことだか さっぱりわかんないよ。)

I don’t know what you’re talking about.

Another common example is してる (doing), which turns into してん:

何してんの? (なにしてんの?)

What are you up to?

まだ勉強してんの? (まだ べんきょうしてんの?)

Are you still studying?

Think of this like abbreviating the words “going to” and “want to” into “gonna” and “wanna.” It’s best not to use this speech pattern in a formal context, but it’s useful to know—especially if you need to search for a word or phrase in a dictionary.

6. Speak Like a Girl or Guy

As you learn conversational Japanese, you’ll notice that men and women tend to use distinct speech patterns.

Depending on where you are, female speakers will often use a polite form of a word (even in casual situations) while male speakers use plain forms of words more often. Sentence-ending particles are also used differently between genders.

You don’t have to be a specific gender to use feminine or masculine manners of speech. However, it’s important to be aware of the slight differences as it will help you better understand your friends and recognize any nuances in your own speech.

でしょう vs. だろう

In this case, でしょう and だろう are both used when you’re presuming something.

If you want to say “Hiro’s room is probably messy”:

ひろくんの部屋は汚いでしょう 。(ひろくんのへやは きたないでしょう。)(female)

ひろくんの部屋は汚いだろう。 (ひろくんのへやは きたないだろう。) (male)

If it’s “I heard Yuki’s sick, so she probably won’t come tonight”:

ゆきちゃんは風邪引いたそうで、今夜来ないでしょう。 (ゆきちゃんは かぜ ひいたそうで、こんや こないでしょう。) (female)

ゆきちゃんは体調悪いそうで、今夜来ないだろう 。(ゆきちゃんは たいちょう わるいそうで、こんや こないだろう。) (male)

As you saw earlier, you can also use でしょう and だろう to show agreement:

A: このケーキは美味しいよ! (このけーきはおいしいよ!)

A: This cake is delicious!)(female)

B: でしょう?

B: Isn’t it?

A: 美味い、このケーキ! (うまい、このけーき!)

A: This cake is delicious! (male)

B: だろう?

B: I know, right?

Since でしょう is more formal sounding, it’s considered more feminine if it’s used in casual conversation. In formal situations, however, it’s gender-neutral and can take the place of でしょうか :

この色はいかがでしょうか? (このいろは いかがでしょうか?)

How about this color?

三時でどうでしょうか? (さんじで どうでしょうか?)

How does three o’clock sound?

ね vs. な

The particles ね and its masculine counterpart な serve many purposes. Their main uses are to seek agreement from the listener (as in “Right?” or “Isn’t it?”), to make a statement or request sound softer or to get someone’s attention (like “Hey!”).

The particle ね can be used by both genders. It does have a gentle ring to it, so it’ll make your speech sound softer. In fact, it sounds more feminine at times. Among friends, guys may use な and だろう instead of ね.

If you’re asking for a favor or making a request, go ahead and use ね:

ここで待っててね。 (ここで まっててね。)

Please wait here.

トムくんによろしくね。 (とむくんに よろしくね。)

Say hello to Tom for me.

If you want to say “It’s hot today, isn’t it,” you can say:

今日は暑いね。 (きょうはあついね。)(female/male)

今日、暑いな。 (きょう、あついな。)(male)

今日、暑いだろう。 (きょう、あついだろう。)(male)

If you want to express agreement or say “That’s right!” these expressions will work best:

そうだね! (female/male)

そうだな! (male)

The “ の ” misconception

The particle の serves many purposes. Aside from being a possessive particle, の can be placed at the end of a sentence to create a question or to give an explanation.

It’s a common misconception that when の is placed at the end of a sentence, it sounds feminine. It can at times, but males use this sentence structure often enough! The particle の is gender-neutral when you are asking a question and expecting an explanation.

For example:

A: 買うの?それ。 (かうの?それ。)

A: You’re buying that?

B: かわいいでしょう?

B: It’s cute, isn’t it? (I’m buying it because it’s cute.)

A: 食べるの? (たべるの?)

A: You’re eating?

B: 朝ご飯を食べなかったの。 (あさごはんを たべなかったの。)

B: I didn’t have breakfast. (I’m eating because I didn’t have breakfast,)

The particle の becomes more feminine when it’s used to ask/answer questions that don’t call for an explanation, or when making a statement:

このかばんは高かったの。 (このかばんは たっかたの。) (female)

This purse was expensive.

It can also be feminine when you combine の with other sentence-ending particles:

彼は悔しいのね? (かれは くやしいのね。)(female)

He’s pretty annoying, isn’t he?

そうなのよ! (female)

You said it!

7. Learn to Embrace Slang

Personally, I tend to shy away from the term “slang.” I hear “slang” and think “street terms” or “language-I-should-only-use-with-really-close-friends.”

Unfortunately, avoiding this part of speech can be detrimental if you’re trying to make “really close friends.” This is because using the formal register can make you feel distant from close colleagues, friends and even host families. If someone is trying to have an intimate or friendly conversation with you, replying to them in a formal manner can sound impersonal.

You can use the following two dialogues as an example:

A: Hey, what’s up?

B: I’m very well, thank you. And yourself?

vs.

A: Hey, what’s up?

B: Nothing much. You?

It’s the same in emails or text messages. What message would you expect from a friend:

Would you like to get lunch with me at noon?

vs.

Wanna grab a bite later?

Which conversation sounds more friendly and intimate? In other words, which conversation makes the speaker sound more fluent?

Of course, the more we hear these conversational tricks and colloquialisms, the easier it becomes to actually use them in your own speech. Native content is key, especially subtitled Japanese movies and variety shows, as the text makes it easier to spot these speech patterns. The interactive subtitles on FluentU’s Japanese media clips also support this kind of contextual learning.

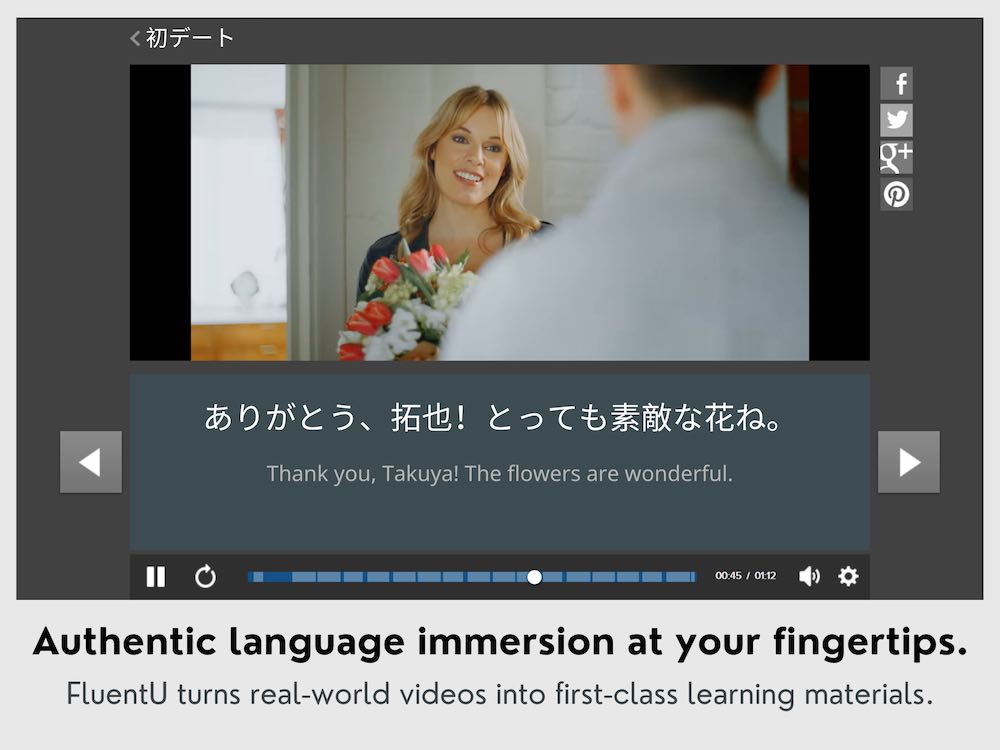

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Remember: your friends, family and that vendor down the street will all forgive you if you make a few mistakes during a conversation. The most important thing is to talk, keep talking and talk some more!

習うより慣れろだよ。 (ならうより なれろ だよ。) Practice is the best teacher!

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing...

If you love learning Japanese with authentic materials, then I should also tell you more about FluentU.

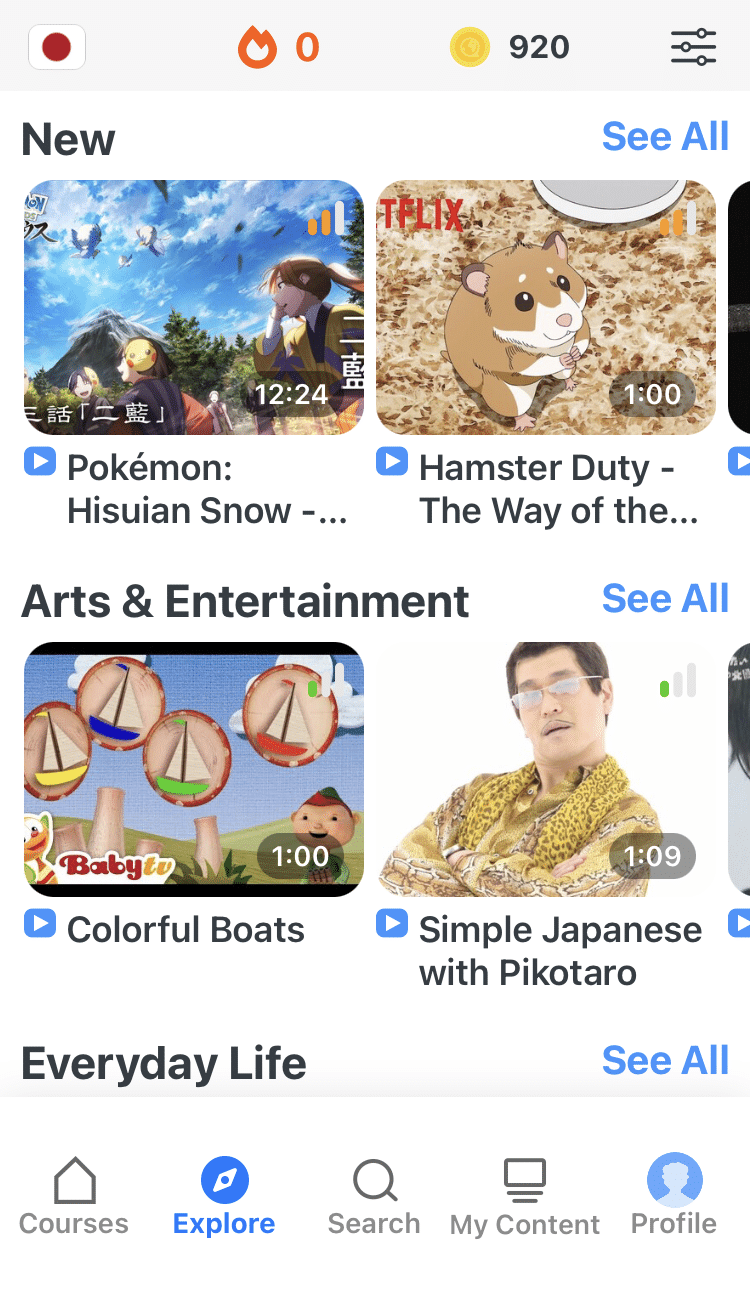

FluentU naturally and gradually eases you into learning Japanese language and culture. You'll learn real Japanese as it's spoken in real life.

FluentU has a broad range of contemporary videos as you'll see below:

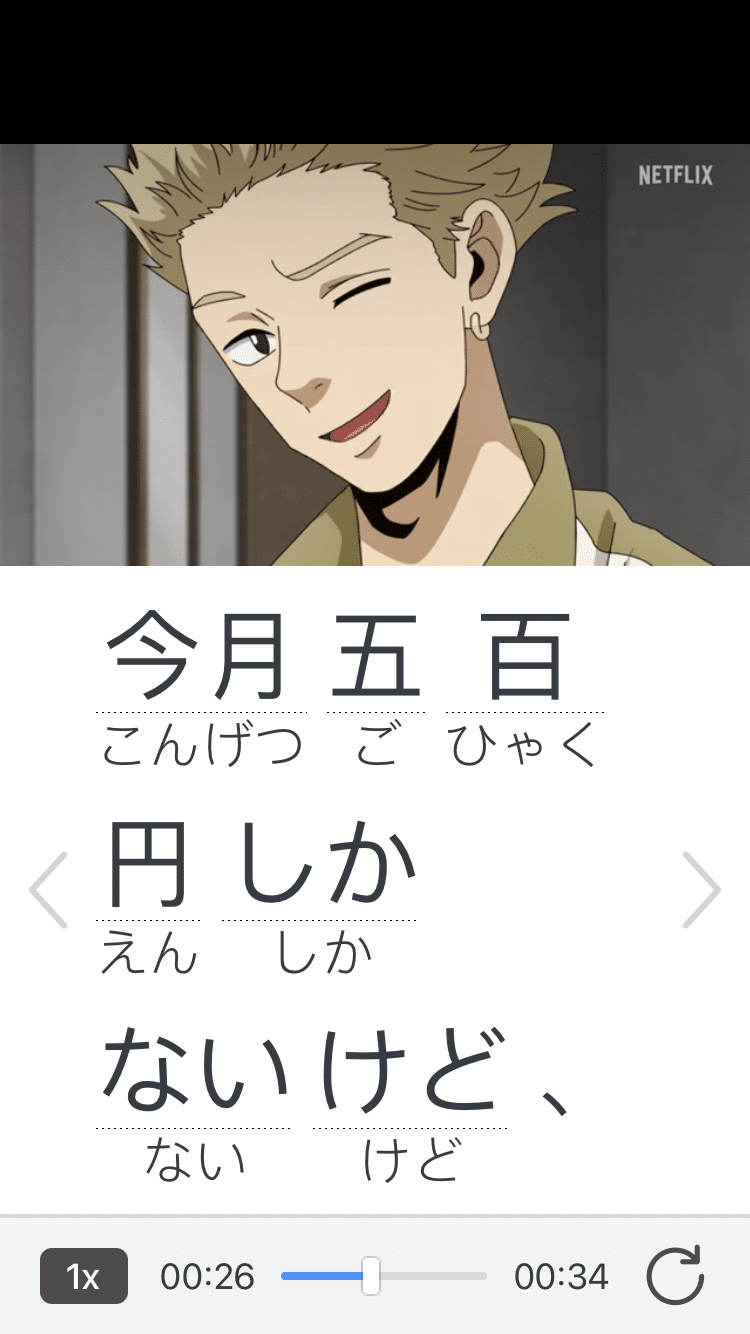

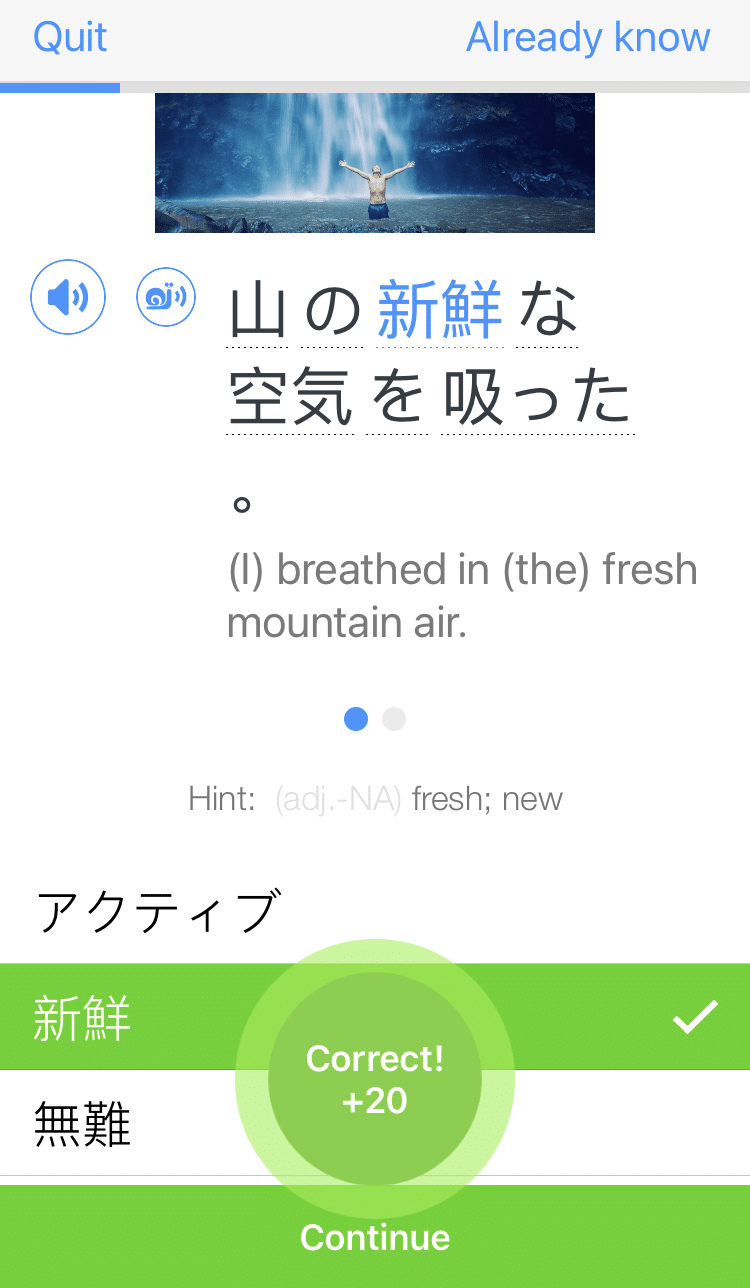

FluentU makes these native Japanese videos approachable through interactive transcripts. Tap on any word to look it up instantly.

All definitions have multiple examples, and they're written for Japanese learners like you. Tap to add words you'd like to review to a vocab list.

And FluentU has a learn mode which turns every video into a language learning lesson. You can always swipe left or right to see more examples.

The best part? FluentU keeps track of your vocabulary, and gives you extra practice with difficult words. It'll even remind you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. You'll have a 100% personalized experience.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)