The Complete Guide to Japanese Pronouns in All Their Forms

In English, referring to someone is as easy as saying “I” and “you.”

Japanese personal pronouns are quite a different matter. Whether you say “watashi,” “boku” or “atashi” can make a world of a difference in how you present yourself to others.

There are many other nuances to learn about Japanese pronouns. Let this guide be your map to proper pronoun usage in your Japanese studies.

Learn all about possessive, reflexive, interrogative and all the other pronouns in Japanese.

Whether you’re chatting with pals or diving into your favorite Japanese show, understanding pronouns like a pro adds a whole new level to your language game!

Contents

- Personal Pronouns in Japanese

- Possessive Pronouns in Japanese

- Reflexive Pronouns in Japanese

- Relative Pronouns in Japanese

- Demonstrative Pronouns in Japanese

- Interrogative Pronouns in Japanese

- Indefinite Pronouns in Japanese

- And One More Thing...

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Personal Pronouns in Japanese

Personal pronouns are used to replace specific nouns, particularly names of people. They’re classified based on the grammatical person (first person, second person and third person) and number (singular or plural).

The main personal pronouns in English are “I,” “you,” “he,” “she,” “it,” “they” and “we.”

In Japanese, there are a number of different ways of expressing personal pronouns, and which one you use can say a lot about yourself. Some personal pronouns are considered more masculine or feminine, formal or informal and some are even downright rude. Below are some of the most common personal pronouns.

Throughout this post, I’ll share plenty of examples for each type of pronoun. Click on any word or example sentence to hear it pronounced! And if you want further help studying each pronoun, I recommend looking them up on FluentU, for plenty of more context in authentic media.

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

First person personal pronouns

- 私 (watashi) — formal, gender-neutral “I”

私は日本が大好きです。 (Watashi wa Nihon ga daisuki desu.) — I love Japan.

- 僕 (boku) — informal masculine “I”

僕は毎日新しいことを学びます。 (Boku wa mainichi atarashii koto wo manabimasu.) — I learn new things every day.

- 俺 (ore) — informal and often masculine “I”

俺は友達と一緒に冒険に行くのが好きだ。 (Ore wa tomodachi to issho ni bouken ni iku no ga suki da.) — I like going on adventures with friends.

More ways to say “I”:

Beyond Watashi: A Quick Guide to Saying “I” in Japanese | FluentU Japanese Blog

Watashi is not the only way to say “I” in Japanese! Check out this guide to learn about 7 different phrases you can use to refer to yourself in Japanese. You’ll learn what…

Second person personal pronouns

- あなた (anata) — informal “you,” sometimes considered rude and too direct

あなたの笑顔は素敵ですね。 (Anata no egao wa suteki desu ne.) — Your smile is lovely.

- 君 (kimi) — informal “you”

君と一緒にいると楽しい時間が過ごせる。 (Kimi to issho ni iru to tanoshii jikan ga sugoseru.) — Spending time with you is enjoyable.

More ways to say “you”:

How to Say “You” in Japanese and Avoid Calling Your Boss “Darling” | FluentU Japanese Blog

Saying “you” in Japanese can be complicated, but this guide will show you five words that you can use to refer to everyone from your spouse to your worst enemy!…

Third person personal pronouns

- 彼 (kare) — He (also means “boyfriend”)

彼は音楽が好きです。 (Kare wa ongaku ga suki desu.) — He likes music.

- 彼女 (kanojo) — She (also means “girlfriend”)

彼女は毎週新しい本を読みます。 (Kanojo wa maishuu atarashii hon o yomimasu.) — She reads a new book every week.

First-person plural pronoun

- 私たち (watashitachi) — formal, gender-neutral “we”

私たちはよく一緒に旅行します。 (Watashitachi wa yoku issho ni ryokou shimasu.) — We often travel together.

- 僕たち (bokutachi) — informal masculine “we”

その部屋を掃除したのは僕たちです。 (Sono heya wo souji shita nowa bokutachi desu.) — We are the ones who cleaned the room.

Third-person plural pronoun

- 彼ら (karera) — mixed-gender or masculine “they”

彼らは新しいプロジェクトに取り組んでいます。 (Karera wa atarashii purojekuto ni torikundeimasu.) — They are working on a new project.

- 彼女たち (kanojotachi) — feminine “they”

彼女たちは一緒に映画を見に行きました。 (Kanojotachi wa issho ni eiga wo mi ni ikimashita.) — They went to see a movie together.

Possessive Pronouns in Japanese

Possessive pronouns are the type that show belonging and ownership, like “my,” “his” and “theirs.” In Japanese, forming the possessive pronoun is as easy as combining the appropriate pronoun with the possessive particle の (no).

- 私の (Watashi no) — My

彼らは私の友達です。 (Karera wa watashi no tomodachi desu.) — They are my friends.

- あなたの (Anata no) — Your (singular)

あなたの意見は重要です。 (Anata no iken wa jūyō desu.) — Your opinion is important.

- 彼の (Kare no) — His

彼の趣味は映画鑑賞です。 (Kare no shumi wa eiga kanshō desu.) — His hobby is watching movies.

- 彼女の (Kanojo no) — Hers

私は彼女の夢が叶うことを願っています。 (Watashi wa kanojo no yume ga kanau koto wo negatte imasu.) — I hope her dreams come true.

- 私たちの (Watashitachi no) — Our

私たちの友情は永遠です。 (Watashitachi no yūjō wa eien desu.) — Our friendship is eternal.

- あなたたちの (Anatatachi no) — Your (plural)

あなたたちの意見を聞かせてください。 (Anatatachi no iken o kikasete kudasai.) — Please share your opinions.

- 彼らの (Karera no) — Their (masculine)

私は彼らの計画に反対した。 (Watashi wa karera no keikaku ni hantai shita.) — I opposed their plan.

- 彼女らの (Kanojora no) — Their (feminine)

彼女らのスタイルは本当に素敵ですね。 (Kanojora no sutairu wa hontō ni suteki desu ne.) — Their style is truly lovely.

Reflexive Pronouns in Japanese

Reflexive pronouns are pronouns that refer back to the subject of the sentence, indicating that the subject is also the recipient of the action. In English, reflexive pronouns are formed by adding the suffix “-self” or “-selves” to personal pronouns, like “myself,” “yourself” and “ourselves.”

Unlike English, which has a range of reflexive pronouns, Japanese primarily uses one word: 自分 (jibun). This versatile pronoun can express self-action in various situations. For example:

- 私自身 (watashi jishin) — literally “I myself”

この計画には私自身の時間を捧げるつもりです。 (Kono keikaku niwa watashijishinn no jikan wo sasageru tsumori desu.) — I intend to dedicate my own time to this plan.

- 彼自身 (kare jishin) — literally “he himself”

彼自身がその計画の主導権を握っています。 (Kare jishin ga sono keikaku no shudōken o nigitteimasu.) — He himself is taking the lead in that plan.

- 私たち自身 (watashitachi jishin) — literally “we ourselves”

私たち自身がこの問題に対処する必要があります。 (Watashitachi jishin ga kono mondai ni taisho suru hitsuyō ga arimasu.) — We ourselves need to address this issue.

You can also use 自分自身 (jibun jishin) to add emphasis to the reflexive action. Use it when you want to highlight the self-directed nature of the action or for clarity. For example:

- 私は自分自身でこの問題を解決する。 (Watashi wa jibun jishin de kono mondai o kaiketsu suru.) — I will solve this problem myself.

Relative Pronouns in Japanese

Relative pronouns are words that introduce relative clauses in a sentence. These pronouns serve as a link between the main clause and the subordinate (relative) clause, providing additional information about a noun or pronoun in the main clause. Common relative pronouns in English include “who,” “whom,” “whose,” “which” and “that.”

Unlike English, Japanese doesn’t have direct equivalents to relative pronouns. Instead, it uses a different approach to express relationships between nouns within a sentence. Here’s a breakdown of this system:

Here are two common ways to create relative clauses in Japanese:

Using 〜の (no)

This particle is often used to indicate possession and is also used to create relative clauses.

For example:

- 読むのが好きな本 (yomu no ga suki na hon) — the book that I like to read

Using 〜こと (koto)

〜こと (koto) is a nominalizing particle that turns a verb into a noun. It can be used to create relative clauses.

- 行ったことがある町 (itta koto ga aru machi) — the town where I have been

Relative clauses in Japanese are flexible, and the choice between using 〜の (no) or 〜こと (koto) depends on the nature of the clause and the verb involved. Understanding these structures is essential for constructing complex sentences in Japanese.

Demonstrative Pronouns in Japanese

Demonstrative pronouns are words used to identify or point to specific nouns in a sentence. They indicate whether the noun is near or far in distance or time. In English, the primary demonstrative pronouns are “this,” “that,” “these” and “those.”

In Japanese, demonstrative pronouns are often expressed using demonstrative determiners along with the noun they modify. The most common demonstrative determiners are これ (kore), それ (sore), あれ (are) and their variations. While these aren’t standalone pronouns, they function similarly to demonstrative pronouns in English.

- これ (kore) — This (for items close to the speaker)

これは私の本です。 (Kore wa watashi no hon desu.) — This is my book.

- それ (sore): That (for items close to the listener)

それはあなたの車ですか? (Sore wa anata no kuruma desu ka?) — Is that your car?

- あれ (are) — That (for items away from both the speaker and the listener)

彼女の家はあれです。 (Kanojyo no ie wa are desu.) — That is her house.

- これら (kore-ra) — These (for items close to the speaker)

これらは新しい商品です。 (Kore-ra wa atarashii shōhin desu.) — These are new products.

- それら (sore-ra) — Those (for items close to the listener)

それらは私の古い漫画です。 (Sore-ra wa watashi no hurui manga desu.) — Those are my old comic books.

- あれら (are-ra) — Those (for items distant from both speaker and listener)

あれらは山の向こうにあります。 (Are-ra wa yama no mukō ni arimasu.) — Those are beyond the mountain.

Additionally, these demonstrative determiners can be combined with the particle “の” (no) to modify nouns directly. For example:

- この (kono)

この車は高額です。 (Kono kuruma wa kougaku desu.) — This car is expensive.

- その (sono)

その携帯電話は壊れています。 (Sono keitai denwa wa kowarete imasu.) — That cellphone is broken.

- あの (ano)

あの建物は古いです。 (Ano tatemono wa furui desu.) — That building is old.

Interrogative Pronouns in Japanese

Interrogative pronouns are pronouns used to introduce questions. They help seek information about people, things, or qualities. In English, the main interrogative pronouns are “who,” “whom,” “whose,” “what” and “which.” Here they are in Japanese:

- 誰 (Dare) — Who

私のコンピュータを勝手に使ったのは誰だ? (Watashi no konpyu-ta wo katte ni tsukatta nowa dare da?) — Who used my computer without permission?

- どなた (Donata) — Who (formal)

どなたがお茶をご希望ですか? (Donata ga ocha o go-kibō desu ka?) — Who would like tea? (formal)

- 何 (Nani) — What

あなたは何がお好きですか? (Anata wa nani ga o-suki desu ka?) — What do you like?

- どこ (Doko) — Where

バス停はどこですか? (Basu-tei wa doko desu ka?) — Where is the bus stop?

- いつ (Itsu) — When

学校を卒業したのはいつですか? (Gakko wo sotsugyo shita nowa itsu desu ka?) — When did you finish school?

- どうして (Doushite) — Why

私は彼がどうしてそんなことを言ったのか分かりません。 (Watashi wa kare ga doushite sonna koto o itta no ka wakarimasen.) — I don’t know why he said such a thing.

- なぜ (Naze) — Why (formal)

なぜこのプロジェクトが遅れているのか説明してください。 (Naze kono purojekuto ga okurete iru no ka setsumei shite kudasai.) — Please explain why this project is delayed. (formal)

It’s important to note that the choice of interrogative pronoun depends on the specific question you want to ask. For example, you would use 誰 (dare) to ask about a person, but 何 (nani) to ask about an object.

Here are some additional interrogative pronouns, used less frequently:

- どの (Dono) — Which (of a specific group)

あなたが好きなのはどの本ですか? (Anata ga suki nanowa dono hon desu ka?) — Which book is your favorite?

- どれくらい (Dore kurai) — How much/many

このプロジェクトにはどれくらいの時間がかかりますか? (Kono purojekuto ni wa dore kurai no jikan ga kakarimasu ka?) — How much time will this project take?

- 何人 (Nanin) — How many people

このクラスには何人の学生がいますか? (Kono kurasu ni wa nanin no gakusei ga imasu ka?) — How many students are in this class?

- いくつ (Ikutsu) — How many (things)

リンゴはいくつありますか? (Ringo wa ikutsu arimasu ka?) — How many apples are there?

- どれほど (Dore hodo) — To what extent

この政策がどれほど効果的かはまだ分かりません。 (Kono seisaku ga dore hodo kōkateki ka wa mada wakarimasen.) — We still don’t know how effective this policy is.

- どんな (Donna) — What kind of

どんな本が好きですか? (Donna hon ga suki desu ka?) — What kind of books do you like?

- 誰の (Dare no) — Whose

この財布は誰のですか? (Kono saifu wa dare no desu ka?) — Whose wallet is this?

- どこの (Doko no) — Where (of something)

この料理はどこの国の料理ですか? (Kono ryōri wa doko no kuni no ryōri desu ka?) — What country’s cuisine is this dish from?

- いつの (Itsu no) — When (of something)

あなたが引っ越したのはいつのことですか? (Anata ga hikkoshita nowa itsu no koto desu ka?) — When did you move?

Indefinite Pronouns in Japanese

Indefinite pronouns are words that don’t refer to any specific person, thing or amount. They’re general and vague, representing non-specific items or individuals. Common examples include words like “everyone,” “someone,” “anybody,” “nothing” and “each.” These pronouns are used when the identity or quantity of the subject is unknown or irrelevant to the context.

Here are some common indefinite pronouns in Japanese:

- 誰か (Dareka) — Someone

誰かがドアをノックしています。 (Dareka ga doa o nokku shiteimasu.) — Someone is knocking on the door.

- 誰でも (Dare demo) — Anyone

このプログラムは誰でも利用できます。 (Kono puroguramu wa dare demo riyou dekimasu.) — Anyone can use this program.

- 誰も (Dare mo) — No one

この部屋には誰もいません。 (Kono heya ni wa dare mo imasen.) — No one is in this room.

- 何か (Nanika) — Something

何か問題がありますか? (Nanika mondai ga arimasu ka?) — Is there something wrong?

- どこか (Dokoka) — Somewhere

彼女はどこかへ旅行に行きたいと言っていました。 (Kanojo wa dokoka e ryokou ni ikitai to itteimashita.) — She said she wants to travel somewhere.

- どこでも (Doko demo) — Anywhere

このチケットはどこでも有効です。 (Kono chiketto wa doko demo yuukou desu.) — This ticket is valid anywhere.

- いつでも (Itsu demo) — Any time

いつでも助けが必要なら教えてください。 (Itsu demo tasuke ga hitsuyou nara oshiete kudasai.) — If you need help anytime, let me know.

Pronouns are such an important part of everyday speech, that it’s crucial to learn them. By getting to the end of this thorough guide to Japanese pronouns, you’re well on your way to sounding more natural in the language. Well done, you!

And One More Thing...

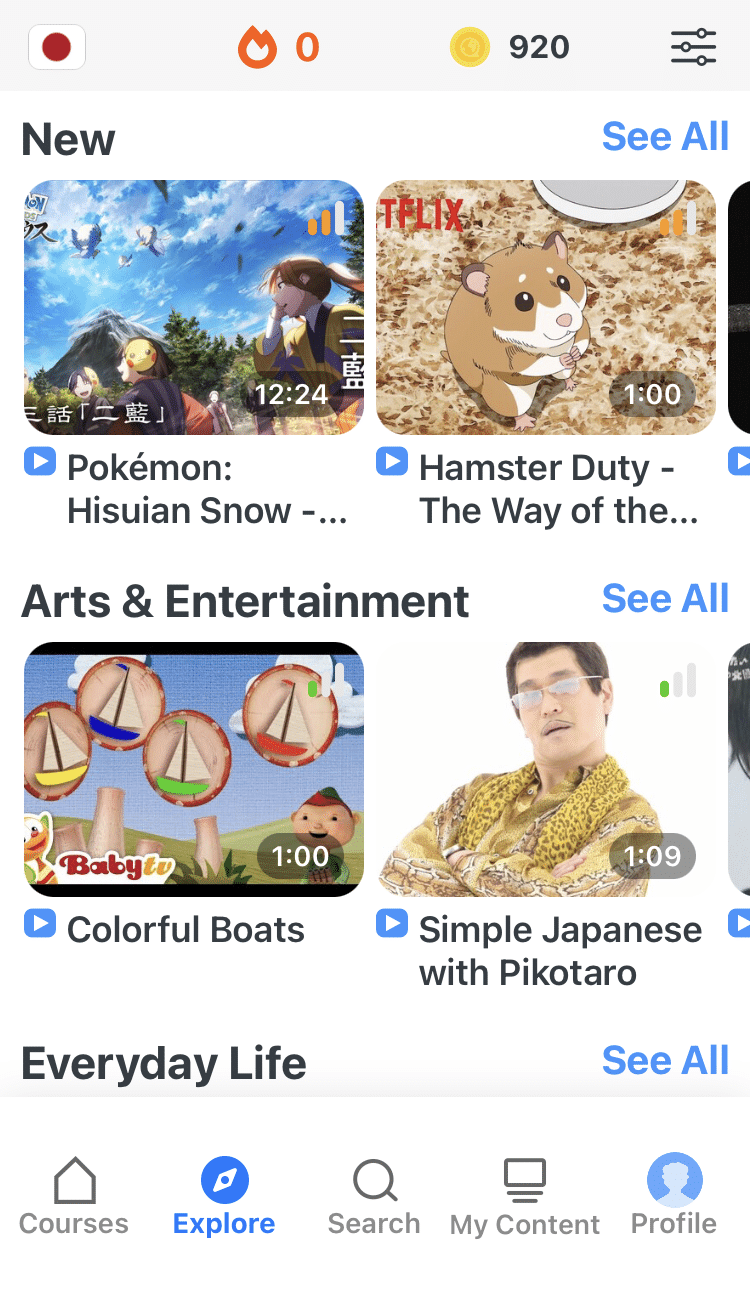

If you love learning Japanese with authentic materials, then I should also tell you more about FluentU.

FluentU naturally and gradually eases you into learning Japanese language and culture. You'll learn real Japanese as it's spoken in real life.

FluentU has a broad range of contemporary videos as you'll see below:

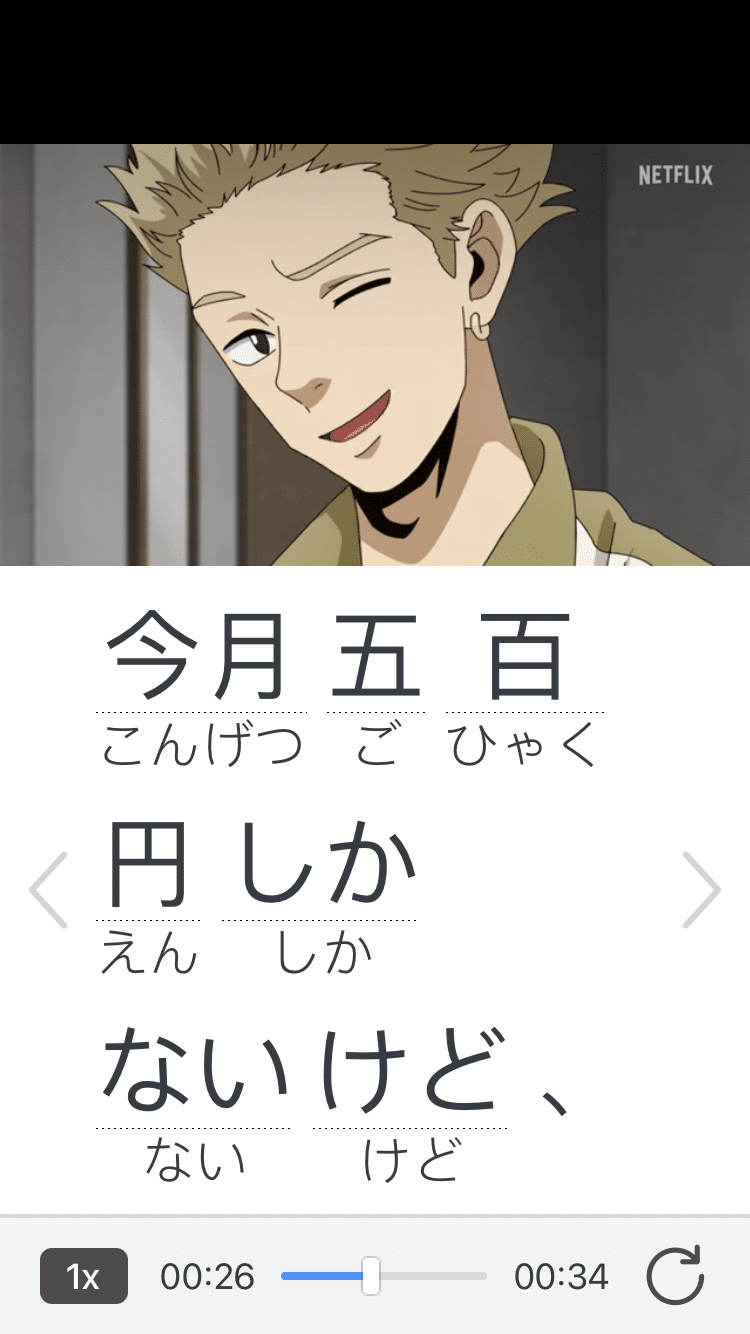

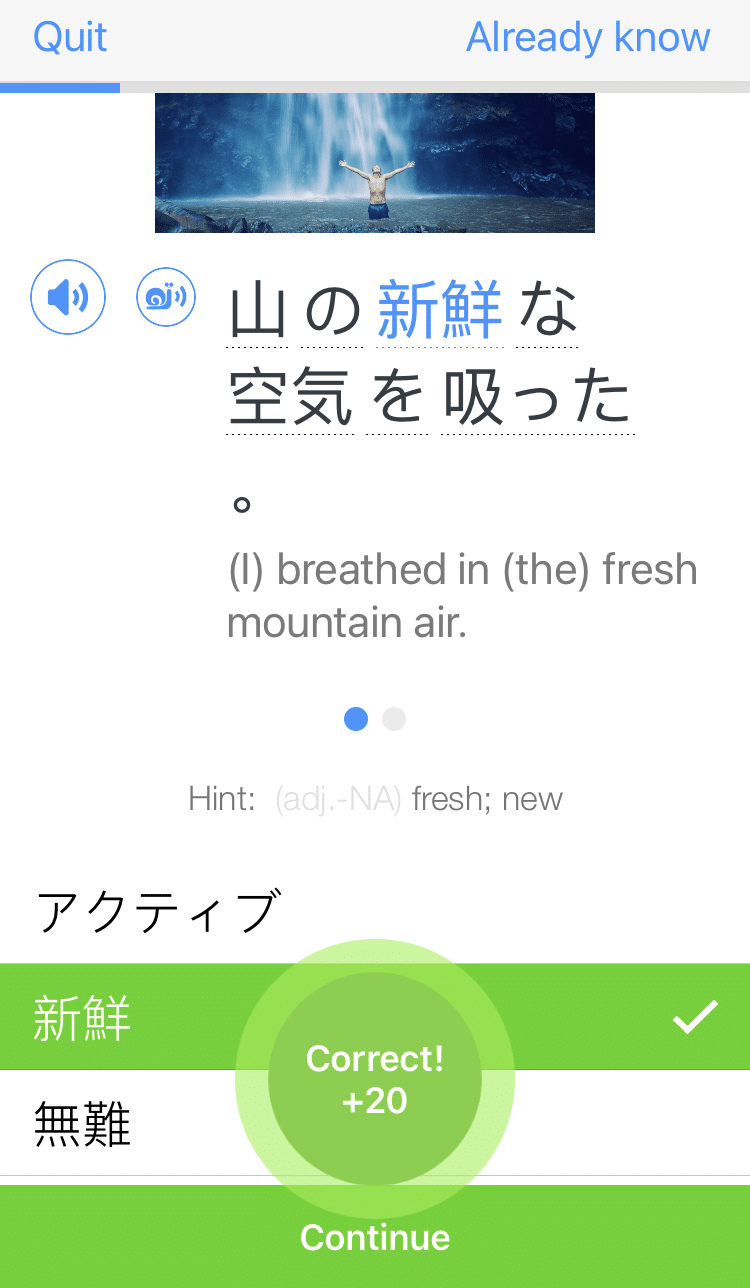

FluentU makes these native Japanese videos approachable through interactive transcripts. Tap on any word to look it up instantly.

All definitions have multiple examples, and they're written for Japanese learners like you. Tap to add words you'd like to review to a vocab list.

And FluentU has a learn mode which turns every video into a language learning lesson. You can always swipe left or right to see more examples.

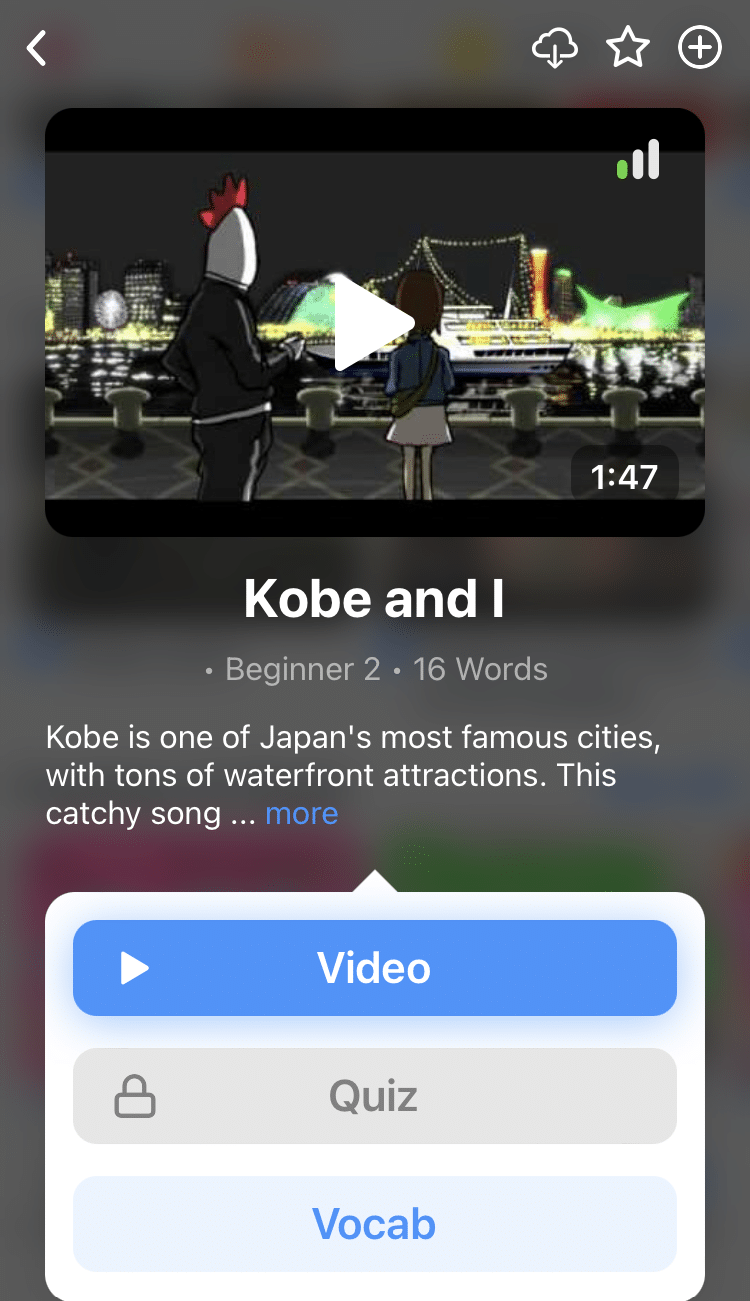

The best part? FluentU keeps track of your vocabulary, and gives you extra practice with difficult words. It'll even remind you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. You'll have a 100% personalized experience.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)