German Articles

Why does German have so many articles? No wonder you can’t remember them all!

In this article, I’ll tell you exactly how to learn German articles quickly and easily.

Let’s get started!

Contents

- What Are Articles?

- The Definite Articles: Der, Die and Das

- The Indefinite Articles: Ein and Eine

- Demonstrative Articles

- Possessive Articles

- How to Remember German Articles

- And One More Thing...

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

What Are Articles?

German articles, which are roughly the equivalent of the and a in English, go alongside nouns. They indicate whether you’re referring to a specific noun (the box) or an unspecified noun (a box).

German articles take many forms to indicate a lot more information about the structure of a sentence.

Cases

German articles are spelled differently in different cases. A noun’s case indicates its relationship to other words in the sentence, like whether it’s the subject or object of a sentence.

There are four cases. Put (very) simply, a noun that’s the subject of a sentence is nominative, a noun that’s the direct object is accusative, a noun that’s the indirect object is dative and a noun that belongs to something else (i.e. showing possession) is genitive.

Gender

German articles also indicate the gender of the noun they’re referring to.

German has three grammatical genders: masculine, feminine and neuter. The rules for determining which nouns are in each category are very complex. Many of them simply have to be memorized.

Number

German articles also change depending on whether the noun is singular or plural. Read our complete guide to plural nouns in German here.

The Definite Articles: Der, Die and Das

Definite articles are the equivalent of the.

Here’s what they look like in each case, for each gender.

| Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | Plural | |

| Nominative | Der | Das | Die | Die |

| Accusative | Den | Das | Die | Die |

| Dative | Dem | Dem | Der | Den |

| Genitive | Des | Des | Der | Der |

Let’s have a look at some examples of these.

Ich gebe dem Lehrer den Apfel. (I give an apple to the teacher.)

Here, Lehrer (teacher) is a singular, masculine noun in the dative case. Apfel (apple) is a singular, masculine noun in the accusative case.

Sie sah das Auto der Ärztin. (She saw the car of the [female] doctor.)

And in this example, Ärztin (doctor) is a singular, feminine noun in the genitive case. Auto (car) is a singular, neuter noun in the accusative case.

The Indefinite Articles: Ein and Eine

Indefinite articles are the equivalent of a/an.

In German, the indefinite article can have various different forms, and like in English, there’s no plural form. When it’s used without an adjective, it takes on a form remarkably similar to the definite article.

| Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | |

| Nominative | Ein | Ein | Eine |

| Accusative | Einen | Ein | Eine |

| Dative | Einem | Einem | Einer |

| Genitive | Eines | Eines | Einer |

Here are a couple of examples to illustrate that usage.

Hier ist eine Frau. (Here is a woman.)

Easy! A singular, feminine noun in the nominative case.

Hier ist eine Frau mit einem Glas. (Here is a woman with a glass.)

Now we’ve added Glas (glass), a singular, neuter noun in the dative case.

So you see, with no adjective between the article and the noun, the indefinite article behaves very much like the definite article.

What happens when we add an adjective?

In that case, the adjective must also be modified depending on the gender and case.

I’ll add the adjective gut (good) to the chart above to illustrate:

| Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | |

| Nominative | Ein guter | Ein gutes | Eine gute |

| Accusative | Einen guten | Ein gutes | Eine gute |

| Dative | Einem guten | Einem guten | Einer guten |

| Genitive | Eines guten | Eines guten | Einer guten |

Now, there are additional rules about adjective declension (modifying a word for gender/case) that fall beyond the scope of this particular discussion.

The most important thing for you to learn right now is how to internalize the gender of each noun.

Demonstrative Articles

Demonstrative articles are a way of specifying a specific noun, usually to the exclusion of another: Not these pineapples, those pineapples.

The demonstrative articles in English are this, that, these, and those. German, on the other hand, only has one– well, one base, dies-, which takes an ending just like other articles. This is how they work in each case and gender:

| Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | Plural | |

| Nominative | dieser | dieses | diese | diese |

| Accusative | diesen | dieses | diese | diese |

| Dative | diesem | diesem | dieser | diesen |

| Genitive | dieses | dieses | dieser | dieser |

You’ll notice it’s pretty much identical to the other charts. The main difference is that dies doesn’t typically stand alone as a base word, the way ein or das do.

Let’s look at some demonstrative articles in action.

Dieser Mann wohnt in diesem Haus. (This man lives in this house.)

Ich nehme diese Jacke mit. (I take this jacket with me.)

Possessive Articles

Possessive articles (also called possessive adjectives or possessive pronouns) are pronouns that show ownership of another noun, like his, your, or our. They may seem tricky at first, since there’s so many pronouns, but they function just like every other article in terms of case and gender.

ichLet’s first go through all of the pronouns we have to work with:

| English | German | German Possessive |

| I | ich | mein |

| he | er | sein |

| she | sie | ihr |

| it | es | sein |

| they | sie | ihr |

| you (formal) | Sie | Ihr |

| you (singular) | du | dein |

| you (plural) | ihr | euer |

| wir | wir | unser |

Mein, sein, and dein are all basically ein with an extra letter at the beginning: they function the exact same way.

That leaves ihr/Ihr, euer, and unser. By now you can probably guess where this is going.

In the neuter form, ihr/Ihr, euer, and unser all stay exactly the same. In the feminine case an -e is added to the end; in the masculine, an -er.

And they change for cases just like normal.

| Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | Plural | |

| Nominative | ihrer eurer unserer | ihr euer unser | ihre euere unsere | ihre euere unsere |

| Accusative | ihren euren unseren | ihr euer unser | ihre eure unsere | ihre eure unsere |

| Dative | ihrem eurem unserem | ihrem eurem unserem | ihrer eurer unserer | ihren euren unseren |

| Genitive | ihres eures unseres | ihres eures unseres | ihrer eurer unserer | ihrer eurer unserer |

The only unusual one is euer. Whenever an ending is added, the second e is dropped. So the masculine becomes eurer instead of euerer, the feminine becomes eure instead of euere, and so on. This may look a little strange on paper, but it’s a lot more natural in speech to say eurem instead of euerem. In all likelihood, you’ll stop noticing it at all after a few practices.

These articles might seem intimidating at first, but as you keep reading and listening to German,, the less you’ll have to consciously memorize these patterns.

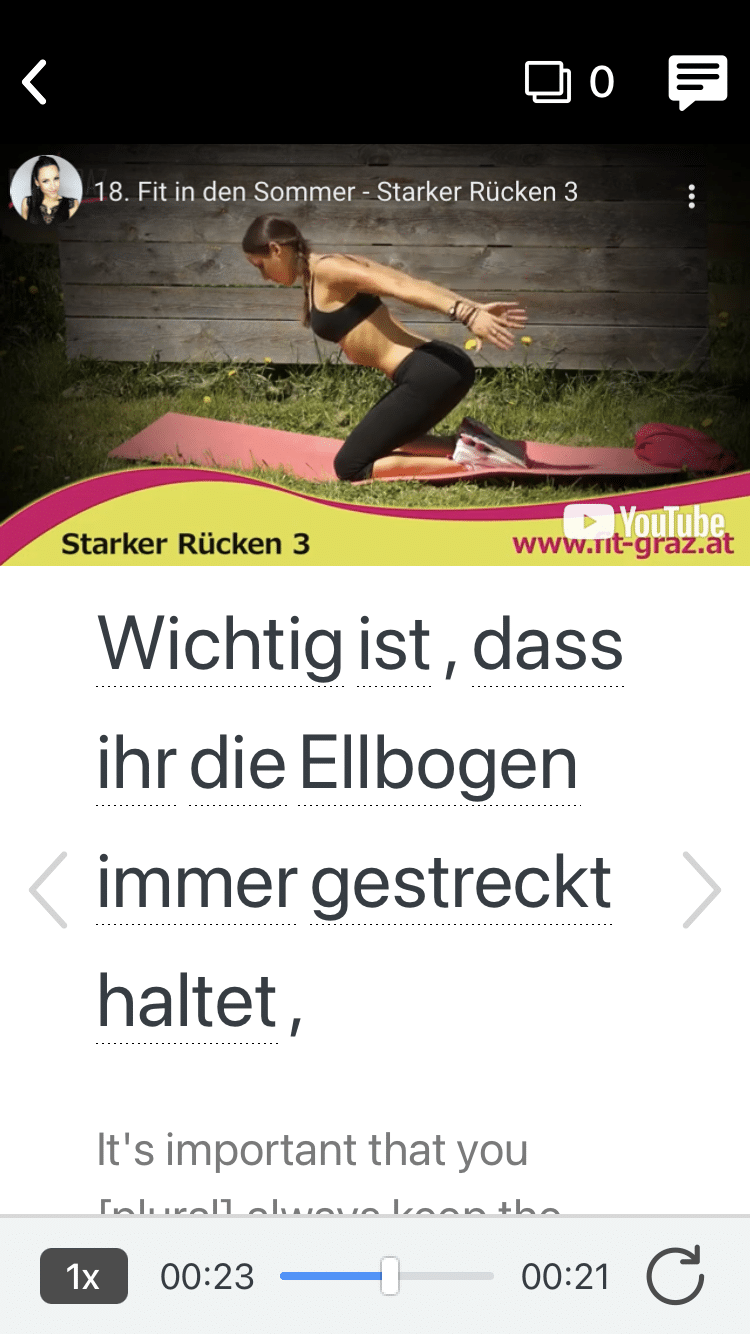

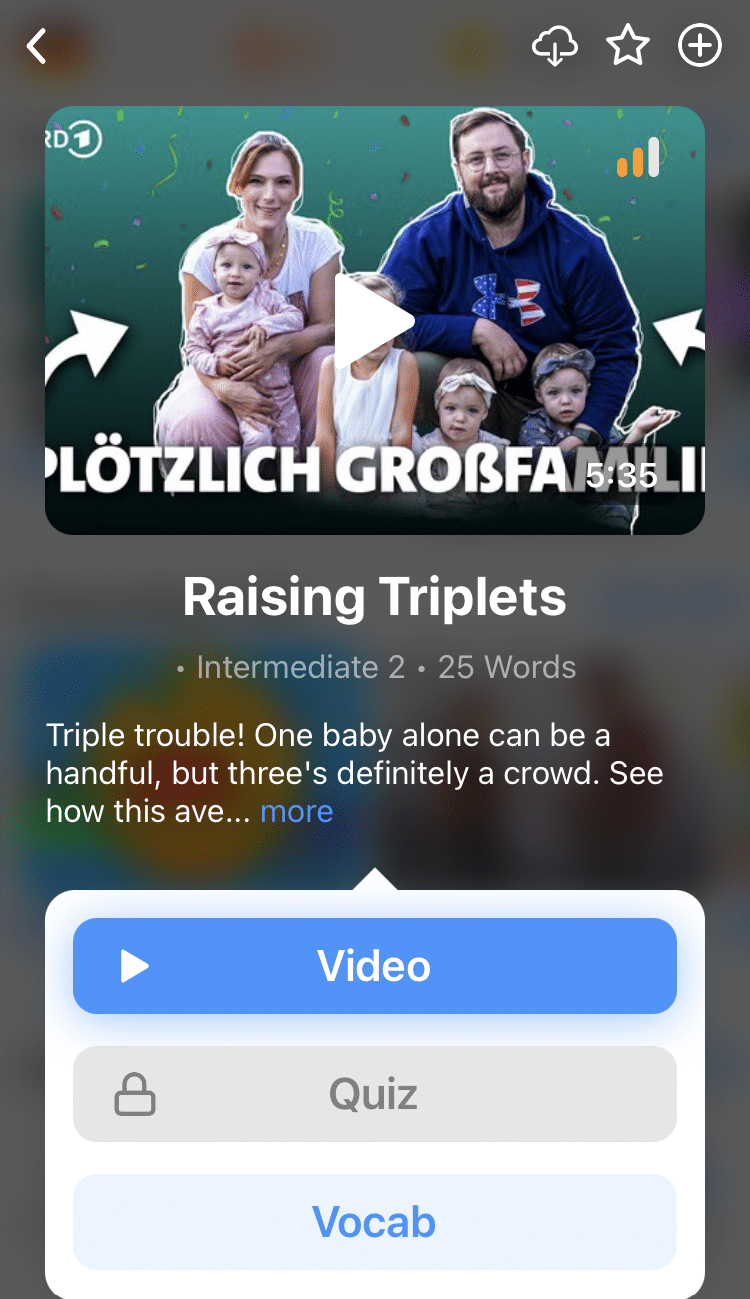

One way to do this is by using a language learning program such as FluentU.

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

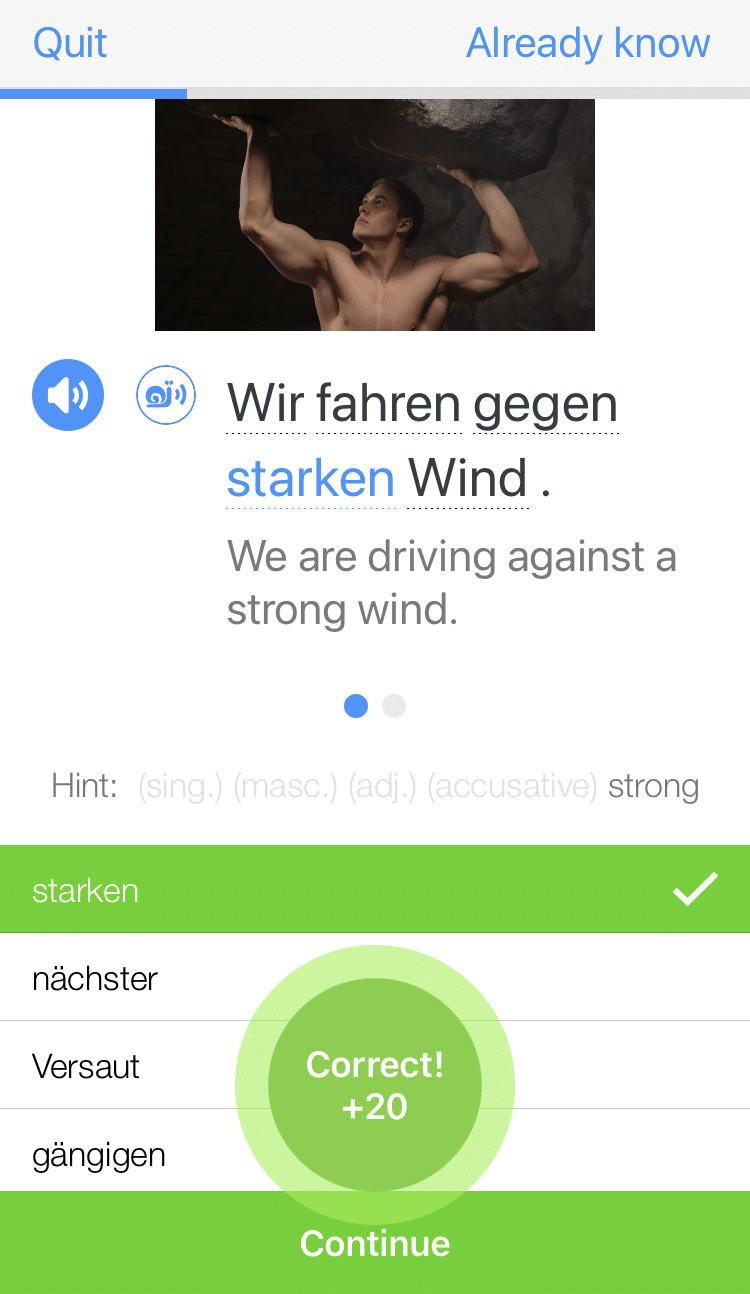

How to Remember German Articles

Why is it that Germans know this stuff and we don’t?

It just sounds right to them to say die Brücke (the bridge) instead of das Brücke, in the same way that English speakers think “change a diaper” sounds better than “switch a diaper.”

Native speakers simply don’t get confused about articles. By hearing, reading and speaking German every day for hours on end since childhood, they’ve absorbed these articles in a fundamental way.

Fortunately, there are a few ways to really nail German articles without that time commitment.

Guess noun genders strategically

Any student of German will probably tell you that the single hardest part of speaking correctly is remembering which article goes with which noun based on its gender.

Perhaps even more so if they’re coming from a language like Italian or Russian, where a word’s gender is fairly predictable based on how it’s spelled.

It turns out though, that German word gender is predictable to an extent as well. You can get most of the way by knowing four things:

- Two-thirds of one-syllable words are masculine. If you guess, you’ve got a good chance of being right!

- Certain word endings are always feminine: -ei, -heit, -keit, -schaft, -ung

- Certain word endings are always neuter: -chen, -ium,-lein, -o, -um

- And here are the ones that are always masculine: -er, -ich, -ismus, -ist

You can now guess the gender of the vast majority of German nouns!

Use straightforward memorization

The stricter you are with yourself when starting out, the better you’ll do memorizing German articles forever.

That means regularly checking yourself on the words you know and the words you’re learning. You can do this very simply.

- Take a German word list that you’re familiar with, perhaps from a textbook, and copy it down without the articles.

- Go do something else for a few minutes to get your mind briefly distracted.

- Come back and try to rewrite all the articles from memory.

If pencil and paper isn’t your thing, you can try an app like Der Die Das on Android or German Articles Buster on iOS.

It might sound like a real grind. But by applying yourself and really forcing yourself to make these things automatic in your speech and writing, you’ll save lots of time in the long run.

Remember set phrases

Once you can reliably produce the article for any given noun you know (putting you, to be honest, well above most German learners), you have to turn that into real language use.

Simply look at a bit of running text like a short article or a subtitled video. Then write down or otherwise point out to yourself the noun phrases. For example, take this line:

In einem deutschen Gasthaus würde man niemals einen Fernseher mit Basketball im Hintergrund sehen. (In a German restaurant one would never see a TV with basketball in the background.)

From this, we can easily parse out the phrases in einem deutschen Gasthaus, einen Fernseher sehen and in dem Hintergrund.

That means in the future when you want to say, for instance, “in a Mexican restaurant” you can simply switch the adjective while keeping the endings intact: in einem mexikanischen Gasthaus.

This way, you pick up and reinforce the adjective ending rules automatically! Again, this is more memorization but just think of it as a fast track to a native-level Sprachgefühl, or “language feeling.”

So there you have it! Now you’re all set to waltz into a beer hall and confidently order a drink using the exact right German articles.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing...

Want to know the key to learning German effectively?

It's using the right content and tools, like FluentU has to offer! Browse hundreds of videos, take endless quizzes and master the German language faster than you've ever imagine!

Watching a fun video, but having trouble understanding it? FluentU brings native videos within reach with interactive subtitles.

You can tap on any word to look it up instantly. Every definition has examples that have been written to help you understand how the word is used. If you see an interesting word you don't know, you can add it to a vocabulary list.

And FluentU isn't just for watching videos. It's a complete platform for learning. It's designed to effectively teach you all the vocabulary from any video. Swipe left or right to see more examples of the word you're on.

The best part is that FluentU keeps track of the vocabulary that you're learning, and gives you extra practice with difficult words. It'll even remind you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)