How Many Chinese Characters Are There? Full Explanation and Guide for Fluency

Some official lists include anywhere from 80,000 to 100,000+ entries.

Even some dictionaries contain up to 20,000 items.

That’s a lot of Chinese characters.

But wait!

The answer to “How many Chinese characters are there?” is very different from the answer to “How many Chinese characters do I need to know?”

In this post, we’ll walk you through the number of Chinese characters, how many you actually need to know, how to learn them and why you should. Let’s begin!

Contents

- How Many Chinese Characters Are There?

- How Many Chinese Characters Do You Need to Know?

- How to Learn Chinese Characters

- Why Learn Chinese Characters?

- And One More Thing...

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

How Many Chinese Characters Are There?

A lot, as you now know!

But, while there’s upwards of 80,000 Chinese characters in total, you only need to know around 2,000 Chinese characters to be literate.

By 3,500 characters, you’ll recognize nearly 99.5% of modern Chinese writing. Even college-educated Chinese people only know around 8,000 characters.

To really understand the Chinese writing system and why these numbers are so different, however, we’ll need to take a closer look at what exactly is being counted and how the whole system works.

The History of Chinese Characters

Chinese characters have actually evolved over thousands of years. The first iterations date all the way back to the Shang Dynasty, which lasted from 1600 to 1046 BC.

Back then, Chinese characters were oracle bone inscriptions, or ancestral pictograms carved onto tortoise shells and animal bones.

These inscriptions were followed by symbols carved into bronze. Bronze inscriptions appeared at the end of the Shang Dynasty and were prevalent during the Zhou Dynasty or “Bronze Age,” which was from 1046 to 771 BC.

The bone and bronze inscriptions were quite similar, but the bronze characters were more structured and had thicker lines.

During the Warring States Period from 475 to 221 BC, there was no standard Chinese script. Different parts of the empire had their own scripts, but all that changed once emperor Qin Shi Huang united China.

The standard written language in the Qin Dynasty (221 to 206 BC) used small seal characters. These had proportional brush strokes and a sort of diamond shape. They’re also the foundation of the contemporary writing system.

The Han Dynasty (206 BC to 220 AD) ushered in the official script. This was where the written language looked less like pictograms and more like characters as we know them, with curved and broken strokes.

At the end of the Han Dynasty, the official script transitioned into the regular script, but it only became popular during the Northern and Southern Dynasties from 420 to 589 AD.

During this era, the regular script continuously underwent stylistic changes. It reached its final form in the Tang Dynasty, which spanned from 618 to 907 AD, and it’s what we’ve come to recognize as traditional Chinese.

It wasn’t until 1954 when the government simplified the traditional characters for printing use. This was to increase literacy throughout China by lessening the number of brush strokes needed to write many common characters.

Traditional Chinese vs. Simplified Chinese

Traditional characters make up the large majority of all Chinese characters.

The government began simplifying characters in the 1950s in order to improve literacy rates. By 1986, over 2,000 characters had been simplified.

According to the Table of General Standard Chinese Characters, there are currently 8,105 simplified characters, although that number includes common characters that remain the same in both forms.

You can read more about the difference between the forms in this post about simplified and traditional Chinese. Here is a video that explains the differences between traditional and simplified characters:

If you’re not sure whether to learn the traditional or simplified form of the language, consider your purpose for learning Mandarin.

Traditional Chinese is preferred in Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan, so if you plan on traveling or moving to one of those places, you’re better off studying the traditional form.

If you’re headed to China, Singapore or Malaysia, simplified Chinese is the way to go. And, in general, there are slightly more learning resources available for simplified characters.

Is There a Chinese Alphabet?

If you’re interested in learning to read and write Chinese characters, you may be wondering… How?

The truth is that there is no Chinese alphabet.

Some people refer to the pinyin system as the Chinese alphabet, but this is inaccurate. Pinyin uses the Latin alphabet to describe the pronunciation of Chinese characters, but it’s not actually used for creating words.

It’s a little confusing, and it doesn’t help that there are 26 letters in both the English alphabet and the pinyin system.

Just know that, unlike Western languages, Chinese doesn’t rely on letters (pinyin or otherwise) to formulate characters and words.

Even if you learn Chinese in Taiwan, which doesn’t use the pinyin system, there is no alphabet. Instead of (or in addition to) pinyin, you will learn the Zhuyin phonetic symbols, but that’s still all they are—a phonetic pronunciation guide, and not the basis of words or characters.

Chinese Radicals and Components

Instead of an alphabet, Chinese characters are composed of building blocks known as radicals and components.

Radicals index and categorize characters. Basically, they’re like the first letter of English words; they’re what we use to look them up in a dictionary. While you can look up words online using pinyin, it’s still pretty handy learning this classification for Chinese characters.

Check out this video to learn more about how radicals work:

For the most part, characters contain one main radical, which you can usually find either on the left or top of the character. There are 214 radicals in total.

An example is 匚 (fāng) which means “box,” and it’s included in characters like 区 (qū) meaning “area” and 匠 (jiàng) meaning “craftsman.”

The other important thing to know is components. There are two types:

- Phonetic components are parts of a character that offer pronunciation clues

- Semantic components are parts of a character that impart some sort of meaning

Radicals can also act as phonetic or semantic components. They may even be referred to as “phonetic radicals” and “semantic radicals.”

Let’s take a look at the character 妈 (mā) for “mother.” It’s composed of two parts:

- 女 (nǚ) — female

- 马 (mǎ) — horse

As you can see, 女 would be the semantic component or semantic radical that indicates the character refers to a female, while 马 would be the phonetic component that shares the same pinyin as 妈, just with a different tone.

Again, though radicals and components help you understand Chinese characters, they’re not the same thing as an alphabet. Many of the 214 radicals are also common words on their own.

Chinese Characters vs. Chinese Words

The final distinction to be aware of is the difference between Chinese characters and Chinese words.

As we just mentioned, some Chinese characters can represent standalone words. They can also represent components for creating other words, ideas and concepts. 女 and 马 from above are perfect examples of characters that are standalone words, as well as components for building other characters.

That means the combinations of characters like those form all kinds of words, which is great news for Chinese learners.

Basically, a handful of Chinese characters can be combined and reorganized to express a wide variety of ideas—you don’t need to learn a brand new Chinese character for every new object or action that you encounter.

For example, check out these characters that are each equivalent to a single English word:

- 吃 (chī) — eat

- 山 (shān) — mountain

- 好 (hǎo) — good

- 火 (huǒ) — fire

- 上 (shàng) — up

- 下 (xià) — down

- 头 (tóu) — head

- 车 (chē) — car

- 人 (rén) — person

Now let’s do a quick exercise. Using the nine characters in the list above, how would you say the following words?

- Volcano

- Mountain top

- Go up the mountain

- Come down the mountain

- Good guy

- Oppressive

- Per capita

- Delicious

- Train

- The front of a car

- Get on (as in getting on a bus)

- Get off (as in getting off of a bus)

Here are the answers:

- 火山 (huǒ shān) — literally “fire mountain”

- 山头 (shān tóu) — literally “mountain head”

- 上山 (shàng shān) — literally “up mountain”

- 下山 (xià shān) — literally “down mountain”

- 好人 (hǎo rén) — literally “good person”

- 吃人 (chī rén) — literally “eat people,” describing someone who takes advantage of other people

- 人头 (rén tóu) — literally “people heads,” kind of like how we say “headcount”

- 好吃 (hǎo chī) — literally “good eat”

- 火车 (huǒ chē) — literally “fire car,” referring to the wood and carbon fires that would power old-style trains

- 车头 (chē tóu) — literally “car head”

- 上车 (shàng chē) — literally “up car,” describing your action getting onto or into a vehicle

- 下车 (xià chē) — literally “down car,” describing your action when getting out of a vehicle

So, although the total number of Chinese characters is very large—and even if the number of characters you personally need to learn to get to a basic level seems large—remember that there are many cases in which you’ll be ahead of the game simply by knowing the most basic characters there are.

How Many Chinese Characters Do You Need to Know?

You can be fluent in English even if you don’t come close to knowing all 1,00,000 estimated words, or even the 470,000 included in the Merriam-Webster dictionary.

Chinese isn’t any different in this respect.

As you just learned, characters are both standalone words and components of other words and ideas. So, really, there are two questions that need an answer here:

- How many characters does one need for fluency?

- How many words does one need for fluency?

Well, the average person only needs to know around 2,000 Chinese characters to be fluent. Those characters represent a basic education level that can help you make it in day-to-day life.

Because Chinese fluency is generally measured by character count, it’s assumed that you’d be able to put those characters into words the way we did with the exercise above. However, that means word count, though a bit harder to quantify, is where your Chinese fluency goals really come into play.

To understand how your vocabulary knowledge impacts your fluency level, I recommend that you follow the standards set by the HSK Chinese proficiency test.

The HSK 2.0 exam is still being administered in many locations. Here are the requirements for that version of the test:

| Level | Basic Requirements | Characters to Know | Words to Know |

|---|---|---|---|

| HSK 1 | use very simple words and phrases | 178 | 150 |

| HSK 2 | exchange simple information | 349 | 300 |

| HSK 3 | communicate at a basic level | 623 | 600 |

| HSK 4 | fluently converse in Chinese | 1,071 | 1,200 |

| HSK 5 | read Chinese newspapers | 1,709 | 2,500 |

| HSK 6 | effectively express yourself | 2,633 | 5,000 |

The new version of the exam, the HSK 3.0, is scheduled to be rolled out worldwide over the next few years. Here’s what is currently known about the updated requirements:

| Level | Basic Requirements | Characters to Know | Words to Know |

|---|---|---|---|

| HSK 1 | have simple communication about familiar topics | 300 | 500 |

| HSK 2 | hold brief conversations about basic social situations | 600 | 1,270 |

| HSK 3 | complete daily interactions involving travel, study and work | 900 | 2,245 |

| HSK 4 | handle everyday conversations, including health issues and job seeking | 1,200 | 3,245 |

| HSK 5 | successfully express opinions, methods and suggestions | 1,500 | 4,315 |

| HSK 6 | hold discussions about professional topics, including issues and conflicts | 1,800 | 5,450 |

| HSK 7 | discuss subjects such as culture, art, sports and emotions with ease | 3,000 | 11,090 |

| HSK 8 | converse about topics including literature, politics, philosophy and religion without difficulty | 3,000 | 11,090 |

| HSK 9 | communicate easily about high-level topics in both casual and professional settings | 3,000 | 11,090 |

Keep in mind that knowing Chinese fluently also depends a lot on context. You might be fluent in English, but that doesn’t mean you can necessarily understand the legalese in a contract or sit in on a random business meeting and grasp all the jargon.

Base your character studies on what you actually read and use outside of your textbook. In other words, make sure you’re learning relevant Chinese characters.

The bottom line, if you really want a character count, is to start by aiming to learn about 2,000 characters. That means you should be able to learn around 3,500 to 4,000 words.

That will get you to basic fluency, around Level 4 of the HSK 2.0 test. Level 6 of that exam is when you can really, effectively express yourself in spoken or written Chinese.

How to Learn Chinese Characters

There are a number of ways you can learn your 2,000 (or however many) characters. Here are just a few.

Read Real Chinese Books

In school, you learn a subject, and you learn new words for that subject that involve related ideas. Basically, you passively learn the language you’re speaking in class.

Look for some Chinese elementary school classroom textbooks on topics that interest you and dig in. You might already know the concepts taught in those books, but you don’t know them in Chinese!

You can also read actual Chinese books—though I recommend starting with either children’s books or graded readers if you’re still at a lower level. Perhaps your ultimate goal could be to read a Chinese novel in its entirety.

Don’t limit your learning to simply memorizing a character and its meaning. Give the character practical context. And whenever you can, include your new words in conversation.

Watch Authentic Chinese Videos

Reading is important, but you’ll be missing a whole other world of the language if you don’t also use Chinese video or audio content. Authentic content is the stuff that Chinese speakers make for other Chinese speakers. It’s the kind of media that native speakers watch on their day off.

When you use this kind of content to learn Chinese, you’re getting the real language. You get to hear words in context and learn them naturally, which goes a long way when it’s time to use them in conversation. That’s why it’s so important to immerse yourself in authentic Chinese TV shows, YouTube channels—even podcasts and audiobooks.

Don’t think that watching authentic content has nothing to do with learning characters, either! There’s usually subtitles for video content, and you can often find transcripts for strictly audio material as well, though the quality of both can be iffy.

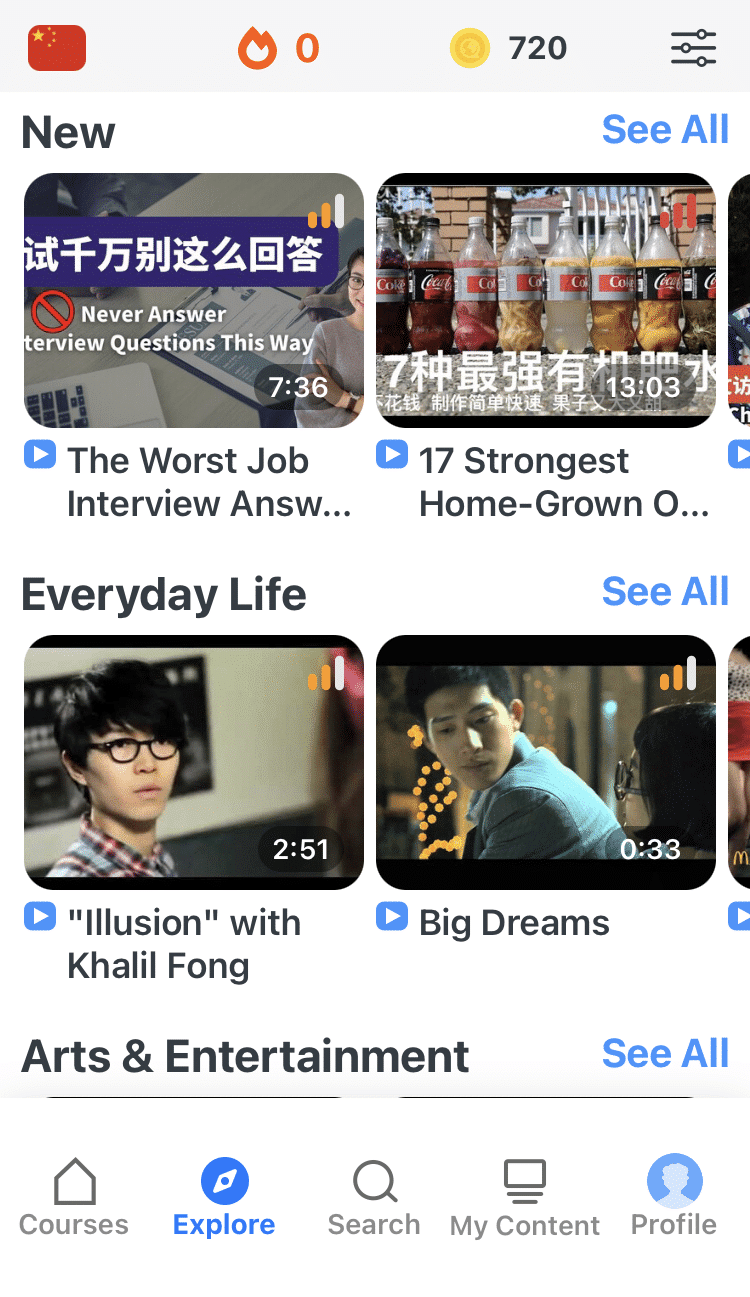

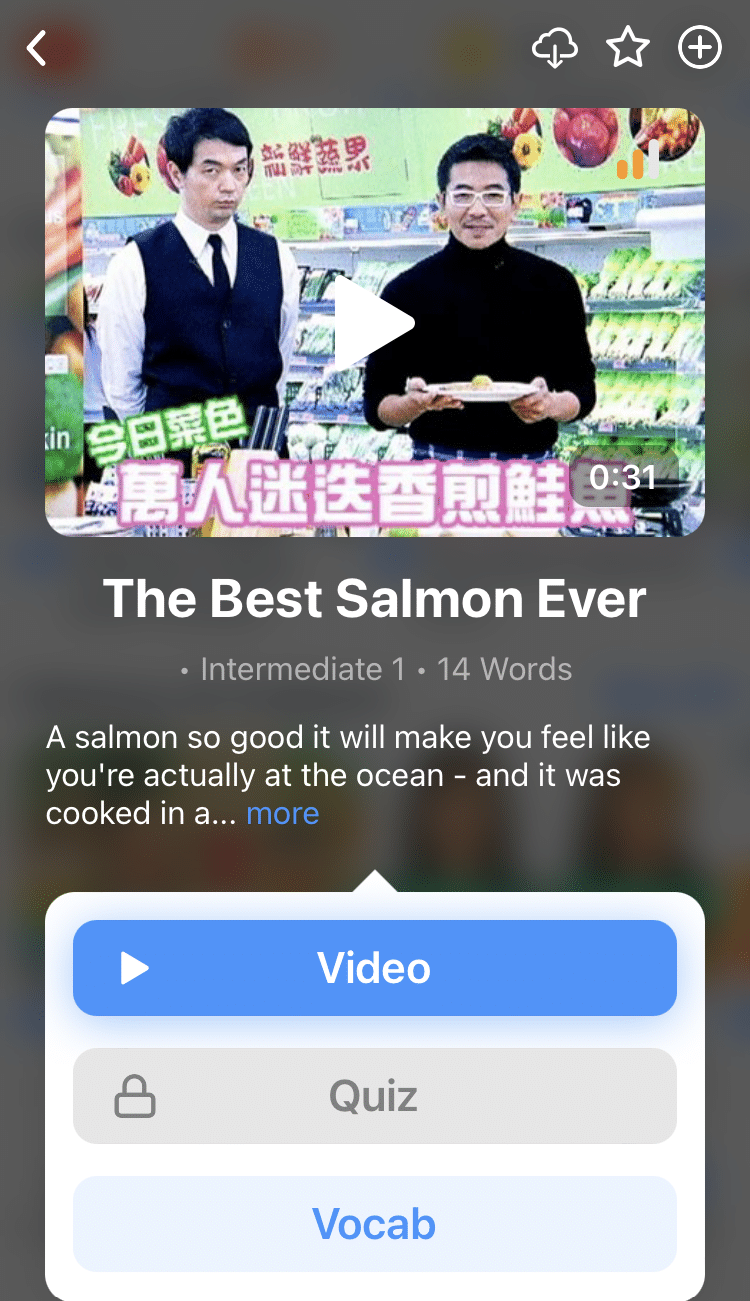

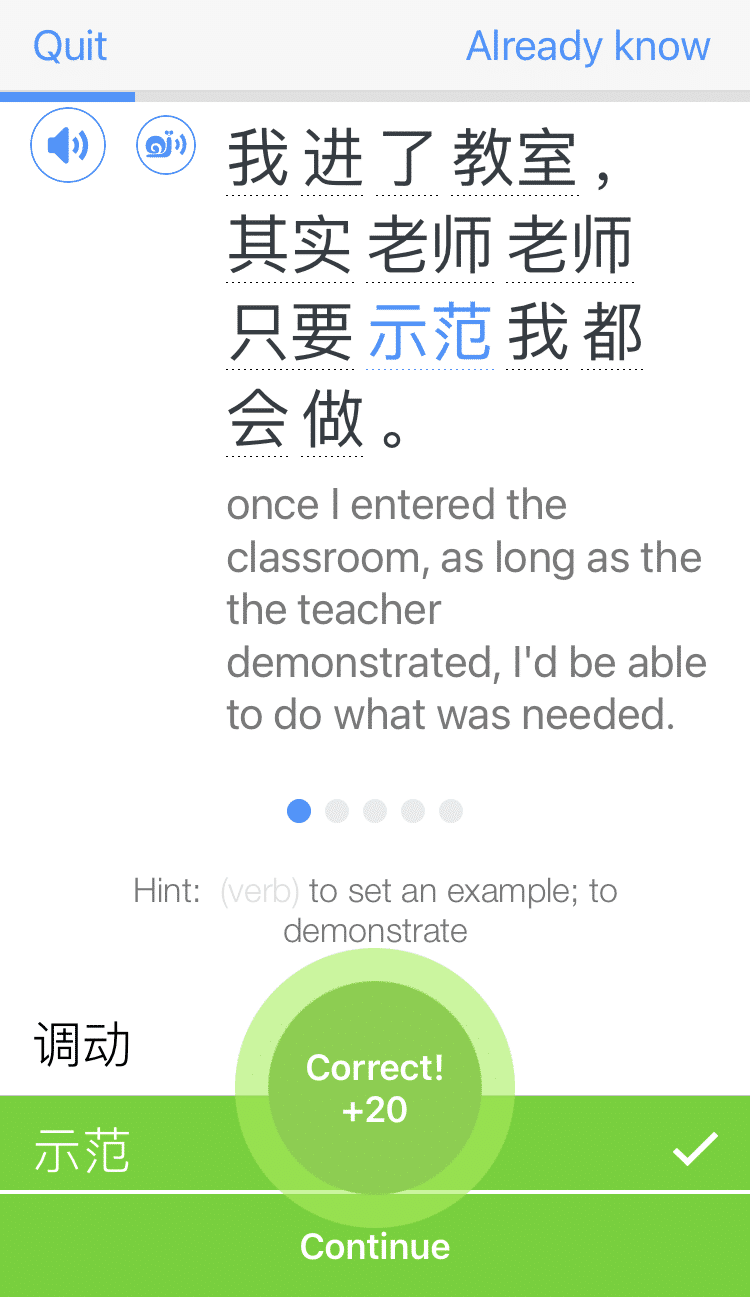

There are also programs designed to help you learn from authentic sources, such as FluentU, where you’re also given expert-vetted subtitles and full transcripts.

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Follow the HSK Levels

The HSK test is based on how you use the characters you know to form words. Following the standards of this language test can lead you to practical success. You can:

- Use HSK Mock tests to study, even if you don’t plan on taking the test. They’ll get you reading and writing with the most important Chinese characters.

- Use apps with sections that show you how characters are used, like the “words” section of Pleco. Pleco even has a built-in HSK vocabulary study list. The more thoroughly you know a character, the more useful it’ll become.

Use the HSK as a guide for character learning, whether or not you plan on taking the exam, and your understanding of Chinese characters will skyrocket.

Why Learn Chinese Characters?

One of the hurdles many Chinese students face is that learning the writing system can seem incredibly daunting. If one can learn to speak Chinese fluently without knowing the characters, then why bother?

It’s not just about writing and reading.

Studying Chinese characters can help you:

- memorize new words

- identify the meanings of unknown words

- understand the language in a more meaningful way

- connect with the culture more deeply

Here’s a personal example: I once bought a fridge for my apartment from a local seller. The seller insisted that we needed to catch a train to get it to the apartment—or so I heard.

Turns out she said 货车 (huò chē) — “delivery truck” and not 火车 (huǒ chē) — “train.” If I’d been familiar with the character 货 (huò), which refers to deliveries or goods, I’d have had a better chance of distinguishing between the words even when spoken.

Characters also help you remember words based on their components. Another example: A classmate of mine once had a discussion about how 安 (ān) — “peace” could be viewed as sexist, since the character is made up of a woman, 女 (nǚ), under a roof, 宀 (mián).

Calligraphy also happens to be an excellent study method. It helps you learn characters by practicing structure and stroke order, and your memory retention for characters will improve, but it also connects you to the culture.

Chinese calligraphy is a highly esteemed form of art in China, and therefore a great way to show some cultural appreciation. Plus, writing and reading this style of Chinese cursive writing will help you later down the line when you’re trying to decipher handwritten text.

So make those Chinese characters work for you. Each character conquered is another step towards Chinese fluency!

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing...

If you want to continue learning Chinese with interactive and authentic Chinese content, then you'll love FluentU.

FluentU naturally eases you into learning Chinese language. Native Chinese content comes within reach, and you'll learn Chinese as it's spoken in real life.

FluentU has a wide range of contemporary videos—like dramas, TV shows, commercials and music videos.

FluentU brings these native Chinese videos within reach via interactive captions. You can tap on any word to instantly look it up. All words have carefully written definitions and examples that will help you understand how a word is used. Tap to add words you'd like to review to a vocab list.

FluentU's Learn Mode turns every video into a language learning lesson. You can always swipe left or right to see more examples for the word you're learning.

The best part is that FluentU always keeps track of your vocabulary. It customizes quizzes to focus on areas that need attention and reminds you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. You have a 100% personalized experience.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)