Simplified vs. Traditional Chinese: How They Differ and Which You Should Learn

The Chinese language has two official writing systems: simplified Chinese and traditional Chinese.

But what’s the difference? Which is more common? Where are they used?

And which should you learn?

We’ll cover these answers and more in this complete guide to simplified vs. traditional Chinese.

Note that Chinese words in this article will be written as “simplified/traditional,” then accompanied by the pronunciation and meaning, as in: 中国 / 中國 (zhōng guó) — China. Characters that are the same in both forms will only appear once.

Contents

- Simplified vs. Traditional Chinese: In a Nutshell

- Differences Between Simplified and Traditional Chinese

- The Four Types of Simplified Characters

- The Historical Significance of Chinese Characters

- Simplified vs. Traditional Chinese: Which Should You Learn?

- And One More Thing...

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Simplified vs. Traditional Chinese: In a Nutshell

Chinese can be written using either simplified characters or traditional characters.

Some examples include:

- 见 / 見 (jiàn) — see

- 车 / 車 (chē) — car

- 发现 / 發現 (fā xiàn) — discover

Traditional Chinese has existed in a recognizably familiar form since at least the first century AD. Simplified Chinese was introduced by the government of the People’s Republic of China in the 1950s in order to improve literacy rates in the country.

Many traditional Chinese characters require significantly more writing strokes than their simplified counterparts. This was in fact the main goal of simplification—to reduce the effort needed to both read and write Chinese characters.

The use of one system versus the other mostly depends on location, as we’ll discuss in more detail below. But while it is easier for traditional users to understand simplified characters than the other way around, both systems use (for the most part) very similar vocabulary, grammar and sentence structures.

Differences Between Simplified and Traditional Chinese

To dive deeper into what makes simplified and traditional Chinese characters different, here’s what you need to know.

Where They’re Used

For quick reference, these are the major Chinese-speaking regions of the world and the characters they use:

| Region | Character Set |

|---|---|

| China | Simplified |

| Taiwan | Traditional |

| Hong Kong* | Traditional |

| Singapore | Simplified |

| Malaysia | Simplified |

*Hong Kong speaks Cantonese Chinese, while the others on this list speak Mandarin Chinese.

Traditional Chinese is used by Chinese speakers in Hong Kong and Taiwan, as well as the majority of Mandarin and Cantonese speakers who live in other countries.

Territories that use traditional characters generally use them exclusively.

Although some locals may be familiar with simplified forms through news channels and online articles, simplified Chinese really hasn’t found its way into everyday life in those areas.

Simplified Chinese is used by both Mandarin and Cantonese speakers living in China, Malaysia and Singapore. Most Cantonese speakers in China live in 广东 / 廣東 (guǎng dōng) — Guangdong province. Because they’re part of China, they use the simplified writing system.

In areas where simplified characters are the main form, traditional characters do show up on occasion in everyday life. They’re generally used in very formal business settings, as well as in any situation involving high-level professional writing (contracts, government papers, etc.).

Traditional characters may also be used by anyone who wants to stand out from others, similar to how cursive script fonts might be used in the US to represent elegance.

What They Look Like

The traditional writing system is regarded as being richer in meaning than simplified. Traditional characters typically contain historical and/or cultural references as well as pictorial descriptions that reflect the thinking of earlier times.

The cultural and historical significance of a character isn’t usually easy to figure out. An example is 发 / 髮 (fà) — hair.

Hair has always had political and social implications in Chinese history. If you had long hair, you supported the controlling rulers. Your long hair would be put up and pinned as part of your coming-of-age ceremony.

If you wore your hair down, you were a rebel or dissenter. If you were being punished, your hair would be cut, or you would be shaved bald.

Notice the top two components of the traditional character for hair, 髮:

- 长 / 镸 (cháng) — long

- 彡 (shān) — hair

Remove those two components, and you’re left with 发, which is the simplified version of the character.

Pictorial characters are a little easier to understand. An example of a pictorial character is 门 / 門 (men) — door. The traditional character looks similar to saloon doors, while the simplified character looks somewhat like a doorframe.

Most characters, both simplified and traditional, have built-in meaning in some way. However, one of the big arguments in favor of traditional Chinese is that the meaning is clearer and deeper.

The most common character used for arguing this point is 爱 / 愛 (ài) — love. In the simplified version, 心 (xīn) — heart has been removed from the middle of the character. You can imagine why many people view this omission as significant!

As arbitrary as the difference in characters may seem sometimes, there is a reason for it, as a lot of simplified characters are based on those from a previously used script—we’ll discuss types of simplified characters as well as older scripts below.

The simplified writing system does have a lot of practical value. The most obvious pro-simplified viewpoint is that it takes less time and is much easier to write.

Consider 发 / 髮 again. The simplified character has five strokes, while the traditional character has 15.

Here are a few more examples:

- 书 / 書 (shū) — book (four strokes vs. 10 strokes)

- 华 / 華 (huá) — magnificent (six strokes vs. 11 strokes)

- 广 / 廣 (guǎng) — wide (three strokes vs. 15 strokes)

Number of Characters

A side-by-side comparison of traditional and simplified characters will show that a good chunk of them are actually the same in both character sets.

According to the Table of General Standard Chinese Characters (2013), there are 8,105 simplified characters, though this number includes those that are the same in both forms.

There are roughly 3,500 characters used commonly (however, knowing about 2,000 characters is usually enough for Chinese learners to successfully get by).

The total number of traditional characters used over the centuries is thought to number over 100,000, but a majority of these are no longer in use or appear only very rarely.

It’s important also to note that traditional and simplified character forms are not always a one-to-one.

Consider again the simplified character 发. To mean “hair,” the traditional counterpart is 髮. In the word “discover,” however, the simplified version uses 发 while the traditional version uses 發: 发现 / 發現 (fā xiàn).

The Four Types of Simplified Characters

So, which characters were simplified? They fall into the following four categories.

1. Components as Characters

These are components of traditional characters that function as their own characters in simplified Chinese, such as 习 / 習 (xí) — habit.

Simply put, these are parts of traditional characters that became their own characters.

The top component of the traditional character, 羽, is an official radical, but the form was further simplified to 习, which was never considered an individual component before the simplification process.

So, the other conditional for this category is that the simplified characters do not function as radicals for other characters. That detail was included so 习 wasn’t mistaken as a radical for the character 羽, which is, again, a full radical by itself.

2. Left-side Radicals

These characters were simplified as left-side radicals but maintained the traditional form when used as other character components or standalone characters.

An example is 言 (yán) — speech/words, which looks the same in both simplified and traditional form, but its radical form became 讠in simplified form so that characters with this radical would have fewer strokes. Take a look:

- 说 / 説 (shuō) — speak

- 语 / 語 (yǔ) — language

- 谈 / 談 (tán) — discuss/converse

Other characters in this category include 食 (shí) — food (simplified as 饣) and 金 (jīn) — metal/money (simplified as 钅):

- 饿 / 餓 (è) — hungry

- 饭 / 飯 (fàn) — food, specifically cooked rice

- 错 / 錯 (cuò) — mistake/error

- 钦 / 欽 (qīn) — admire/respect

Note that when these characters function as a component and not as a left-side radical, they keep their traditional form:

- 誓 (shì) — oath

- 鉴 / 鑒 (jiàn) — reflect

- 餐 (cān) — meal

Characters also keep their traditional form when paired with other characters to form words:

- 语言 / 語言 (yǔ yán) — language

- 食物 (shí wù) — food

- 现金 / 現金 (xiàn jīn) — cash

3. Fully Simplified

The third category of simplified characters were simplified regardless of whether they functioned as a radical, component or individually as part of a word.

Characters in this category include:

- 见 / 見 (jiàn) — see

- 现 / 現 (xiàn) — present

- 觉 / 覺 (jué) — sense/feel

- 见面 / 見面 (jiàn miàn) — meet up

4. Shorthand Characters

These characters were simplified based on shorthand versions of characters and may be completely different from their traditional counterparts.

An example of this is 卫 / 衛 (wèi) — defend/guard.

The center component of the traditional character is 韋, which has a simplified version: 韦. But because the shorthand version of the simplified character, 卫, made it even easier, that was chosen as the official simplified version.

Another example of a simplification that doesn’t seem to fit the rules is 夸 / 誇 (kuā) — exaggerate.

It seems like this character should have the simplified 言 radical 讠to the left of 夸. However, it wasn’t simplified that way because the form 夸 was already an officially accepted form of the traditional character 誇 in other types of script.

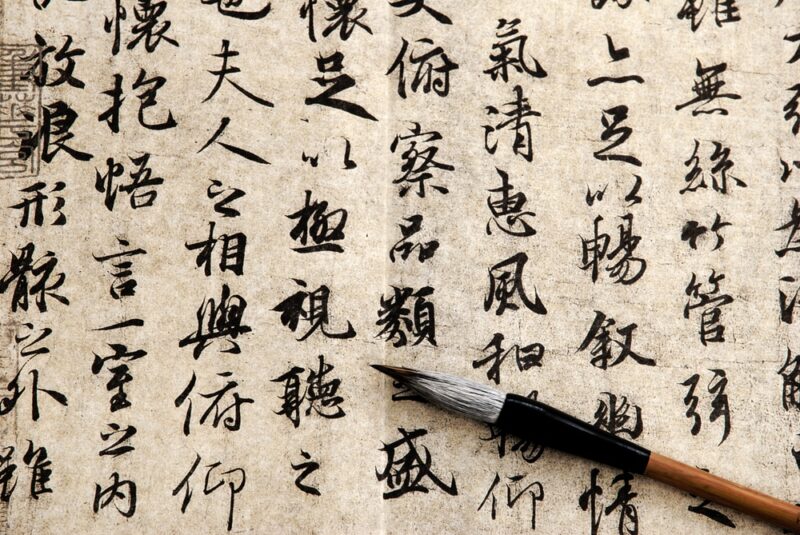

The Historical Significance of Chinese Characters

When I encountered native Chinese speakers in the States, I asked them which writing system they prefer. The answer was usually “traditional”—often said with a very strong, slightly offended tone.

The use of simplified characters can be a hot button issue.

Here’s a little bit of the cultural history to help you understand why, starting with the seven historical Chinese scripts. These are the four that evolved into today’s traditional Chinese writing:

- 甲骨文 (jiǎ gǔ wén) — Oracle Bone Script, which is about 3,500 years old. This script was mainly pictographs, or very simple pictures representing objects.

A pictograph and its opposite (for example, “rain” and “no rain”) would be etched into turtle shells or animal bones. The shells or bones would be heated until cracks appeared, and the cracks pointed to the answer to the question. (This is why “oracle” is part of the name.)

- 大篆 (dà zhuàn) — Greater Seal, about 3,100 years old. This script existed around the same time as the oracle bone script but was written on cast bronze vessels. There’s a slight difference between the two, mostly because of the material they were written on.

- 小篆 (xiǎo zhuàn) — Lesser Seal. This is regarded as the forerunner to modern traditional Chinese. It was the first script to use radicals and become less pictorial.

- 隶书 / 隸書 (lì shū) — Clerical Script. This was mainly used by government officials. The characters in the script have fewer strokes and a more flowing style of writing than Lesser Seal. It made writing faster, especially with a brush. Clerical Script and traditional characters have the same forms.

After Clerical Script, Chinese writing got more and more cursive-like. These are the three scripts used today, mostly in calligraphy:

- 楷书 / 楷書 (kǎi shū) — Standard Script. This is a slightly more stylized version of Clerical Script, using only traditional characters. Certain Clerical Script strokes were straight lines, but in Standard Script, they finish with a slight hook to give the character… character.

- 行书 / 行書 (xíng shū) — Running Script. This is the cursive version of Standard Script, and a lot of strokes are combined into one, much like how English cursive works.

- 草书 / 草書 (cǎo shū) — Grass Script. This is cursive-ness to the extreme. There are more combined strokes than in Running Script, and some strokes are completely left out.

As new scripts were developed through the dynasties, Chinese writing became more and more functional.

Pronunciation keys were added, the concept of radicals was introduced and character components were added, giving indications of the meaning. These still exist in today’s traditional Chinese writing system.

The arguments for a simplified character set began in the early 1900s, but simplification wasn’t implemented until the People’s Republic of China was formed in 1949. Interestingly, the eventual goal of character simplification was to completely Romanize the Chinese writing system.

This is why pinyin was invented and promoted around the same time. The simplified characters were developed and promoted in education systems in the 1950s with the goal of increasing literacy, especially among the older population.

The plan seems to have worked. When the simplified writing system was first being taught, China’s literacy rate was around 20%. The literacy rate is now estimated to be around 95%.

People in favor of traditional characters argue that the simplified writing system has outlived its purpose. After all, children in Hong Kong and Taiwan do perfectly fine learning traditional characters.

Those who advocate for simplified characters continue to argue that the simplified set still has advantages in more rural areas where formal education isn’t so accessible.

Regardless of which political or social viewpoint you have, understanding the differences between simplified and traditional Chinese characters will help you better understand the language as a whole.

Simplified vs. Traditional Chinese: Which Should You Learn?

If you’re trying to learn Chinese, the question of which characters you should focus on is (usually) pretty easy to answer. First, ask yourself these three questions:

- Where will you be traveling/living? If you will be traveling or living in a place that uses simplified characters, then that’s going to benefit you most. If the place uses traditional characters, go traditional.

- Who will you most commonly communicate with in Chinese? Maybe you won’t be living in a predominantly Chinese-speaking region. Maybe you just have friends or family who speak the language. Perhaps you live in an area where Chinese is a minority language. If that’s the case, choose the version that the people around you use.

- Which character set do you find more interesting? If you like the deeper meanings and history of the traditional characters, learn traditional. If you like to be able to read small fonts and want to write more quickly, simplified might be the way to go.

One important note is that simplified Chinese is the more common writing system, simply because China has way more people than the other areas that use Chinese. (Don’t write off traditional characters just because of numbers, though!)

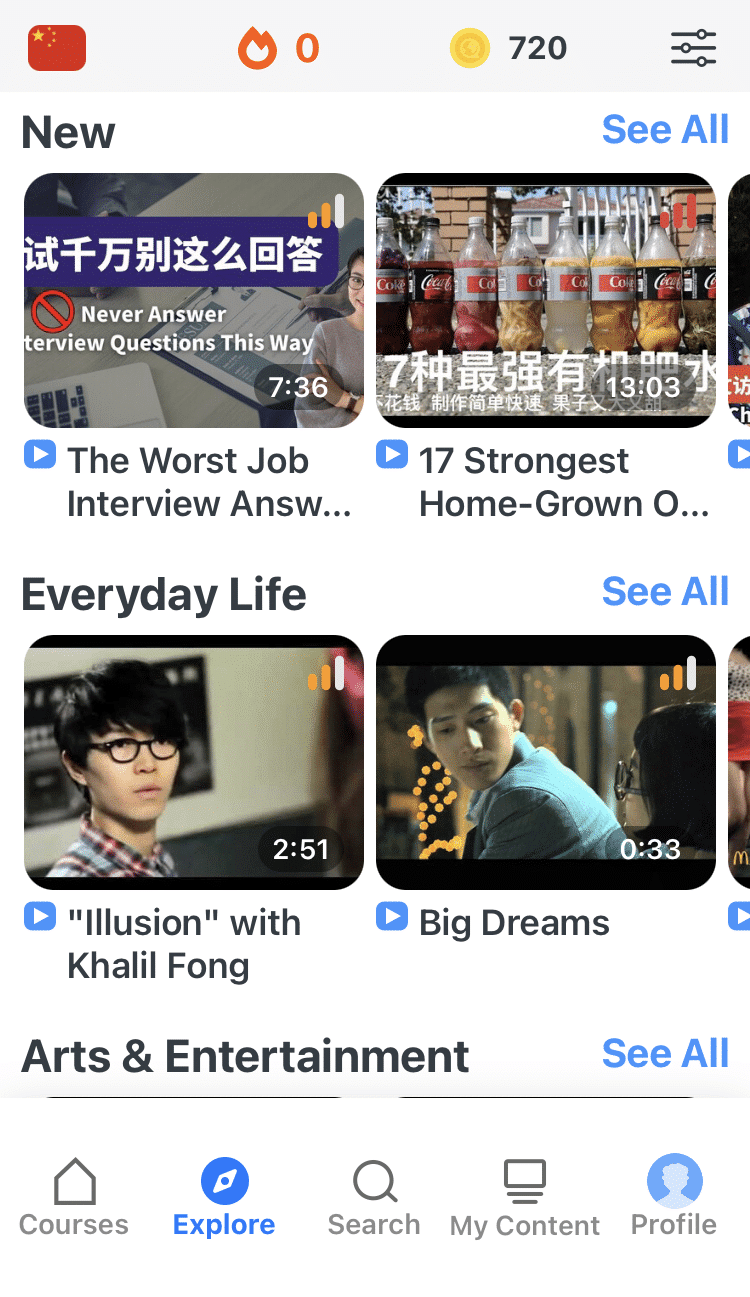

While there is a slight bias in learning resources towards simplified characters because of this, many Chinese language learning apps and programs allow you to choose which characters you want to study.

For example, FluentU is a video-focused language learning program that lets you display either simplified or traditional Chinese in the subtitles.

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Digital learning resources are convenient for a variety of reasons, and the ease of choosing between traditional and simplified Chinese is definitely one of them.

The ability to write well earns sincere respect from Chinese people (they know it’s difficult, especially for foreigners!).

And using the form of the language that the locals use will certainly endear you to them, whether you’re a student, business traveler or just someone who’s interested in Chinese.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing...

If you want to continue learning Chinese with interactive and authentic Chinese content, then you'll love FluentU.

FluentU naturally eases you into learning Chinese language. Native Chinese content comes within reach, and you'll learn Chinese as it's spoken in real life.

FluentU has a wide range of contemporary videos—like dramas, TV shows, commercials and music videos.

FluentU brings these native Chinese videos within reach via interactive captions. You can tap on any word to instantly look it up. All words have carefully written definitions and examples that will help you understand how a word is used. Tap to add words you'd like to review to a vocab list.

FluentU's Learn Mode turns every video into a language learning lesson. You can always swipe left or right to see more examples for the word you're learning.

The best part is that FluentU always keeps track of your vocabulary. It customizes quizzes to focus on areas that need attention and reminds you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. You have a 100% personalized experience.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)