9 Chinese Conversation Scripts to Prepare You for Real-world Dialogues

Textbook Chinese dialogues are the worst.

It doesn’t matter how many times you read through the conversations—once you go to a restaurant in China, you’ll likely be thrown for a loop within a sentence or two.

That’s because we can’t predict exactly what someone will say in any given situation.

Think of the Chinese dialogues in this post as guides—you don’t need to memorize them exactly.

Instead, these nine scripts will give you a sense of conversational flow and the kind of questions and responses you might run into in the real world to help prevent you from freezing up.

Let’s begin!

Contents

- Chinese Conversation Openers

- Chinese Dialogues to Use with Anyone

- Chinese Dialogues for Use in Your Country

- Chinese Dialogues to Use in China

- Helpful Phrases for Any Chinese Conversation

- Politeness in Basic Chinese Conversation

- And One More Thing...

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Chinese Conversation Openers

Before you start any conversation, you want to make sure that approaching someone in Chinese will not be offensive. People of other Asian nationalities probably won’t appreciate you assuming they’re Chinese.

If you aren’t sure whether the other person is Chinese or not, you can say “Hello” in English along with your 你好 (nǐ hǎo). Saying 你好 will work for you because you’re foreign, though it’s generally not how Chinese people greet each other.

If you can confirm that someone is Chinese before you start a conversation with them (for example, if you overhear them speaking Chinese), then you can skip the 你好 greeting altogether.

In that case, a much more natural way to start a conversation in Chinese is to state the obvious.

It’s like the way an English speaker might use a rhetorical question, like asking a colleague, “Hey, done with lunch?”—even though it’s clear that the colleague has already finished eating and gone back to work.

So in Chinese, you can try out these neutral conversation starter statements with a friend, a colleague, an acquaintance, your boss or even a stranger!

- 你回来了!(nǐ huí lái le!) — You’re back!

- 你来了!(nǐ lái le!) — You made it/You’re here!

- 好久不见!(hǎo jiǔ bù jiàn!) — Long time no see!

- 吃饭了吧。(chī fàn le ba.) — You’ve already eaten. (This is similar to asking “I take it you’ve already eaten?” and can be used if you’re meeting up with someone close to a mealtime. It’s also just a polite way to greet someone.)

- 最近很忙吧。(zuì jìn hěn máng ba.) — [It seems like] You’ve been busy lately.

- 你的新工作已经开始了吧。(nǐ de xīn gōng zuò yǐ jīng kāi shǐ le ba.) — So your new job has started.

- 这里的咖啡很好喝。(zhè lǐ de kā fēi hěn hǎo hē.) — The coffee here is great.

- 今天天气还不错。(jīn tiān tiān qì hái bù cuò.) — The weather is pretty good today.

Chinese Dialogues to Use with Anyone

These conversations can be used almost anywhere. You’ll have greater success if you can tweak the script to really fit your location and situation, but these base-level interactions will serve you well as is!

For each dialogue, you are person A and your conversation partner is person B.

Talk about them

Who doesn’t like talking about themselves sometimes? Inviting someone to do so is a great way to start a conversation.

The follow script could be a conversation in its own right, or simply the intro to a longer chat. Of course, if you’re in China, you’ll probably be safe skipping the first question.

A: 你是中国人吗?

(nǐ shì zhōng guó rén ma?)

Are you from China?

B: 是啊!

(shì ā!)

I am!

A: 中国哪里?

(zhōng guó nǎ li?)

Where in China are you from?

B: 我是__的。

(wǒ shì __ de.)

I’m from __.

A: 在那里有方言吗?

(zài nà li yǒu fāng yán ma?)

Is there a dialect in that area?

B: 有。

(yǒu.)

There is.

A: 你的母语是普通话吗?

(mǐ de mǔ yǔ shì pú tōng huà ma?)

Is Mandarin your mother tongue?

B: 是的 / 不是。

(shì de / bú shì.)

It is / No, it’s not.

Note that to answer the question 中国哪里?they may say either a Chinese province or a Chinese city, which you can learn more about here.

Talk about the weather

To expand on the above conversation (or start a new one—notice the conversation opener below!), you can engage the other person in further questions about their background, hometown or nationality.

Just as in English, these topics are fair game for small talk in the Chinese-speaking world.

A: 今天天气还不错。

(jīn tiān tiān qì hái bù cuò.)

The weather is pretty good today.

B: 是啊!

(shì a!)

True!

A: 请问,您是哪里人?

(qǐng wèn, nín shì nǎ lǐ rén?)

May I ask, where are you from?

B: 我是哈尔滨人。

(wǒ shì hā ‘ěr bīn rén.)

I’m from Harbin.

A: 哇, 哈尔滨!那里的天气怎么样?

(wa, hā ‘ěr bīn! nà lǐ de tiān qì zěn me yàng?)

Wow, Harbin! What is the weather like there?

B: 哈尔滨的天气非常冷!

(hā ‘ěr bīn de tiān qì fēi cháng lěng!)

Harbin’s weather is very cold!

To really be prepared for this conversation, brush up on your Chinese weather vocabulary. You can also practice including information about your own hometown and corresponding weather as well.

Talk about recent activities

Another casual conversation you can have (especially if you really hit it off with someone) is discussing what you or they have been up to.

This also works great if you run into an acquaintance or friend you haven’t see in a while. Here’s a sample dialogue between two old pals:

A: 好久不见!

(hǎo jiǔ bù jiàn!)

Long time no see!

B: 是的!

(shì de!)

Yeah!

A: 你最近怎么样?

(nǐ zuì jìn zěn me yàng?)

How have you been recently?

B: 我最近很忙。你呢?

(wǒ zuì jìn hěn máng. nǐ ne?)

I’ve been very busy. What about you?

A: 我也很忙,我每天都在学中文!

(wǒ yě hěn máng, wǒ měi tiān doū zài xué zhōng wén!)

I’ve been busy too. I’ve been studying Chinese every day!

B: 能听得出来!你的发音很有进步!

(néng tīng de chū lái! nǐ de fǎ yīn hěn yǒu jìn bù!)

I can hear the difference! Your pronunciation has really improved!

An easy continuation of this conversation could be asking them what hobbies they’ve been enjoying in their free time.

Talk about work

If you work with native Chinese speakers, they will probably greatly appreciate you learning their language.

Striking up a casual conversation with Chinese-speaking colleagues is a great way to build camaraderie and language skills.

Before diving into a work-related request or asking for help on a project, try easing into your conversation with a dialogue like this:

A: 你回来了!

(nǐ huí lái le!)

You’re back!

B: 回来了!

(huí lái le!)

I’m back!

A: 吃饭了吧?

(chī fàn le ba?)

You ate already?

B: 吃完了。

(chī wán le.)

[Yes,] I ate.

A: 那请问,你现在有空吗?

(nà qǐng wèn, nǐ xiàn zài yǒu kòng ma?)

Then may I ask, are you free right now?

B: 有,怎么了?

(yǒu, zěn me le?)

Yeah, what’s up?

A: 你可以帮我回一封邮件吗?

(nǐ kě yǐ bāng wǒ huí yī fēng yóu jiàn ma?)

Can you help me reply to an email?

B: 可以,没问题!

(kě yǐ, méi wèn tí!)

Sure, no problem!

Chinese Dialogues for Use in Your Country

The following few conversations are great to learn because you can ask a lot of the same questions and end up having totally different interactions in each situation.

Don’t forget to start with a basic greeting or quick “get-to-know-you” question first!

Talk to a Chinese worker

Perhaps you’ve bumped into a Chinese speaker out and about in your hometown. You can strike up a chat like this:

A: 你读书还是上班?

(nǐ dú shū hái shi shàng bàn?)

Are you studying or working here?

B: 上班。

(shàng bàn.)

Working.

A: 你住在这里多久了?

(nǐ zhù zài zhè li duō jiǔ le?)

How long have you lived here?

B: 我__年搬到这里了。

(wǒ __ nián bān dào zhè li le.)

I moved here in __ [referring to the year].

A: 习惯了吗?

(xí guàn le ma?)

Have you gotten used to living here?

B: 习惯了。

(xí guàn le.)

[Yeah,] I’ve gotten used to it.

There are, of course, plenty of alternative answers the other person could give in this conversation. For instance, other answers to the question 你住在这里多久了?may include:

- 已经__年了。(yǐ jīng __ nián le.) — It’s already been __ years.

- 已经__个月了。(yǐ jīng __ gè yuè le.) — It’s already been __ months.

- 就__天了。(jiǔ __ tiān le.) — It’s only been __ days.

- 我__年来了。(wǒ __ nián lái le.) — I got here in __ [referring to the year].

If it was recent enough, they may just tell you the date they arrived.

In Chinese, durations of time are generalized. The only two components you really need for this answer are duration of time (years, months, days, etc.) and numbers (one to 10 generally are good enough).

Another answer to 习惯了吗?could be 还没 (hái méi) — “Not yet.” Or, they might say 不习惯 (bù xí guàn) to mean “Not used to it,” which would usually be said when they’ve given up hope of getting accustomed.

Talk to a Chinese student

This conversation could start from the same questions as the last one. See where it diverges:

A: 你读书还是上班?

(nǐ dú shū hái shi shàng bàn?)

Are you studying or working here?

B: 读书。

(dú shū.)

Studying.

A: 你住在这里多久了?

(nǐ zhù zài zhè li duō jiǔ le?)

How long have you lived here?

B: 已经__个月了。

(yǐ jīng __ gè yuè le.)

It’s already been __ months.

A: 喜欢这边吗?

(xǐ huān zhè biàn ma?)

How do you like it here?

B: 不错!

(bú cuò!)

It’s not bad!

A: 你的父母还在中国吗?

(nǐ de fū mǔ hái zài zhōng guó ma?)

Are your parents still in China?

B: 还在。

(hái zài.)

They are.

Again, there are a range of answer options here, some of which we went over above.

In this example, the student answered 喜欢这边吗?with 不错, meaning “not bad” or “I’m liking it so far.” They could also say:

- 不太喜欢。(bú tài xǐ huān.) — I don’t like it so much. (As in, “I’m only here because I have to be.”)

- 还可以。(hái kě yǐ.) — It’s good. (As in, “It’s doable.”)

- 喜欢。(xǐ huān.) — I like it here. (As in, “Two thumbs up.”)

Next, the answer to 你的父母还在中国吗?could also be 不在 (bú zài) — “They aren’t.”

If the person is older, however, you may not want to ask about their parents for obvious reasons. It would be more appropriate to ask: 你的家人也在这里吗?(nǐ de jiā rén yě zài zhè li ma?) — “Is your family here, too?”

Talk to a Chinese traveler

We started the last two conversations with the same question: 你读书还是上班?

The word 还是 means “or” and creates a sort of multiple choice question for the other person to select one of the two options you’ve presented—in this case, working or studying.

But what if they’re not doing either?

In that case, they’ll likely respond by telling you what they’re doing instead. The most common answer: 旅游 (lǚ yóu) — traveling.

Here’s how you can continue chatting with a Chinese traveler:

A: 你多长时间在这边?

(nǐ duō cháng shí jiān zài zhè li?)

How long will you be here?

B: 一共__天。

(yǐ gōng __ tiān.)

In total __ days.

A: 你和家人一起旅游吗?

(nǐ hé jiā rén yī qǐ lǚ yóu ma?)

Are you traveling with your family?

B: 我一个人旅游。

(wǒ yī gè rén lǚ yóu.)

I’m traveling by myself.

A: 喜欢这边的天气吗?

(xǐ huān zhè biàn de tiān qī ma?)

How do you like the weather here?

B: 喜欢!

(xǐ huān!)

I like it!

A: 你觉得走来走去容不容易?

(nǐ jué de zǒu lái zǒu qù róng bù róng yì?)

Do you think it’s easy to get around here?

B: 可以的。

(kě yǐ de.)

It’s manageable.

Alternative responses to 你和家人一起旅游吗?might include:

- 和家人一起。(hé jiā rén yī qǐ.) — [Yes,] I’m with family.

- 我和__。(wǒ hé __.) — It’s me and __. (Likely a family member or 朋友 [péng yǒu] — friend.)

- 我出差了。(wǒ chū chāi le.) — I’m on a business trip.

And did you notice how we changed 喜欢这边吗?to 喜欢这边的天气吗?in this dialogue?

Adding this 的 + Noun structure is great for conversations, because it means, “Do you like the __ here?” You can try replacing 天气 with 菜 (cài) — food, or 人 (rén) — people.

Chinese Dialogues to Use in China

The following scripts will help you connect with locals as you travel through China or other Chinese-speaking regions.

Again, remember to start with a greeting or conversation opener!

Talk to a taxi driver

One of the most reliable conversation partners of any traveler is the curious cabbie.

In China, these drivers are so famously chatty that they’ve inspired entire blog posts about the full-immersion experience of learning Chinese in taxis!

Here’s how an example conversation could go:

A: 早上好。我要去语言学校。

(zǎo shang hǎo. wǒ yào qù yǔ yán xué xiào.)

Good morning. I’m going to the language school.

B: 好。

(hǎo.)

OK.

A: 请问,现在几点?

(qǐng wèn, xiàn zài jǐ diǎn?)

Excuse me, what is the time now?

B: 差一刻八点。您会说汉语啊?

(chà yī kè bā diǎn. nín huì shuō hàn yǔ a?)

It’s a quarter to eight. You can speak Chinese?

A: 我会说一点儿汉语。我现在要去上汉语课了。

(wǒ huì shuō yī diǎn er hàn yǔ. wǒ xiàn zài yào qù shàng hàn yǔ kè le.)

I can speak a little Chinese. I’m going to Chinese class right now.

B: 你们几点上课?

(nǐ men jǐ diǎn shàng kè?)

What time do you guys have class?

A: 八点上课。师傅,我们八点能到吗?

(bā diǎn shàng kè. shī fù, wǒ men bā diǎn néng dào ma?)

We have class at eight o’clock. Driver, can we arrive by eight?

B: 能到。您的汉语很好。

(néng dào. nín de hàn yǔ hěn hǎo.)

Yes, we can. Your Chinese is good.

Talk to a local

If you’re in an interesting area and want to get chatty, find someone nearby who seems friendly and give it a go!

A: 你是本地人吗?

(nǐ shì běn dì rén ma?)

Are you a local?

B: 是的。

(shì de.)

I am.

A: 我是__的。你认识过__人吗?

(wǒ shì __ de. nǐ rèn shi guò __ rén ma?)

I’m from __. Have you ever met a __ before?

B: 认识过。

(rèn shi guò.)

I have.

A: 你去过别的国家吗?

(nǐ qù guò bǐe de guó jiā ma?)

Have you been to any other countries?

B: 我去过__。

(wǒ qù guò __.)

I’ve been to __.

To say where you’re from, simply fill in the name of your country in Chinese. The name of a country followed by 人 (person) means someone is “a citizen of” said country. For example, 美国 (měi guó) means “America,” and 美国人 (měi guó rén) means “American.”

Other possible answers to “Have you met a __ person before?” might be:

- 我没有。(wǒ méi yǒu.) — I have not.

- 这是第一次。(zhè shì dì yī cì.) — This is the first time.

- 你是第一个。(nǐ shì dì yī gè.) — You’re the first.

If your conversation partner has never left China, they could answer 你去过别的国家吗?with 没去国外 (méi qù guó wài) — “I haven’t been to another country.”

Lastly, if they answer the first question with 不是 (bù shì), meaning that they’re not a local of the place you’re in, you could also ask them: 你喜欢__吗?(nǐ xǐ huān __ ma?) — “Do you like [the name of the city or province you’re in]?”

To this they might say some phrases you’ve already learned, like:

- 不太喜欢。(bú tài xǐ huān.) — I don’t like it that much.

- 还可以。(hái kě yǐ.) — It’s good/okay.

- 不错。(bú cuò.) — It’s not bad/pretty good.

- 喜欢。(xǐ huān.) — I like it here.

Helpful Phrases for Any Chinese Conversation

Memorizing these common phrases will help you out if any of your conversations go so off-track that you’re having trouble following along or keeping up.

不好意思 (bù hǎo yī si)

This is most commonly used like “Excuse me” is in English. You can use this phrase to apologize when you don’t understand what the other person is saying.

Of course, try to take the conversation sentence by sentence and not word by word. If you get the gist of what they’re trying to say—roll with it! And if it turns out later that you missed something important, you can apologize then.

(You can also learn the chorus to this song!)

对不起 (duì bù qǐ)

This is how you say “I’m sorry” in Chinese. It carries more weight than 不好意思, so it’s better to save this one for when you need to apologize because you have to chalk up the conversation as a loss (it happens).

Learning to apologize as a Chinese learner is culturally important. Apologizing for not understanding the other person shows that you won’t demand that they come down to your level of Chinese.

It also shows that you want to communicate with them despite your language limitations. An apology can be viewed as both respectful and endearing. After all, it’s not their fault they went “off script!”

没听懂 (méi tīng dǒng)

The literal meaning of this phrase is “Didn’t hear and get it,” which implies that while you did hear what they said, you don’t know what it means. Use 没听懂 when the other person says a word or phrase that you’ve never heard before.

Note that there’s a very similar phrase, 听不懂 (tīng bù dǒng), that basically means the same thing, but you’d say it as a reason to end a conversation instead of ask for explanation.

不明白 (bù míng bái)

Literally “Don’t understand,” the implied meaning here is “I heard and understood what you said, but I don’t understand your point.”

You can use this phrase if you know the words the other person is saying, but you don’t get the gist of what they’re trying to communicate.

不知道什么意思 (bù zhī dào shén me yī si)

What you’re saying with this phrase is, “I don’t know what [that] means,” as in “I don’t understand what that has to do with what we’re talking about.”

If you understood every word that was said and what those words or phrases mean on their own, but you don’t understand how it fits into the context of the conversation, you can say 不知道什么意思.

To be more specific about what you didn’t understand, you can say: [word/phrase]什么意思?(__ shén me yī si?) to ask “What does [word/phrase] mean?”

Politeness in Basic Chinese Conversation

To further hone your conversational prowess, try starting questions with 请问 (qǐng wèn) — “Excuse me” or “Please, may I ask…”

This is a polite way to start a question when speaking with someone you don’t know (or don’t know well), or someone who may hold a respected status—such as a manager, teacher or elderly family member.

In the latter scenario, you can also consider switching any instances of 你 (nǐ) — “you” to 您 (nín) — the honorific form of “you.”

Further, if you find yourself struggling to carry on a conversation, you can try ending responses with 你呢?(nǐ ne?) — “and you?” Like in English, this can be added onto responses like “I’m doing well” or “I’ve been busy lately” to bounce the question back to your partner.

Most Chinese dialogue scripts follow the same, very basic structure: a greeting, then a Chinese-language-based conversation. Again, the downside of a script is that, in real life, the other person could say anything at any point during the conversation.

You can continue preparing for this by consuming more realistic Chinese content. Movies and television will give you great examples of how native speakers really hold conversations in Chinese.

For help selecting the right video clips to watch, you can try using FluentU, an immersive language learning program. The video clips on this program come from authentic Chinese media, so you’ll learn the language as it’s actually spoken by native speakers.

Review the nine Chinese dialogues in this post and expose yourself to more Chinese conversations, and you’ll feel more and more prepared each time you meet a native Chinese speaker!

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing...

If you want to continue learning Chinese with interactive and authentic Chinese content, then you'll love FluentU.

FluentU naturally eases you into learning Chinese language. Native Chinese content comes within reach, and you'll learn Chinese as it's spoken in real life.

FluentU has a wide range of contemporary videos—like dramas, TV shows, commercials and music videos.

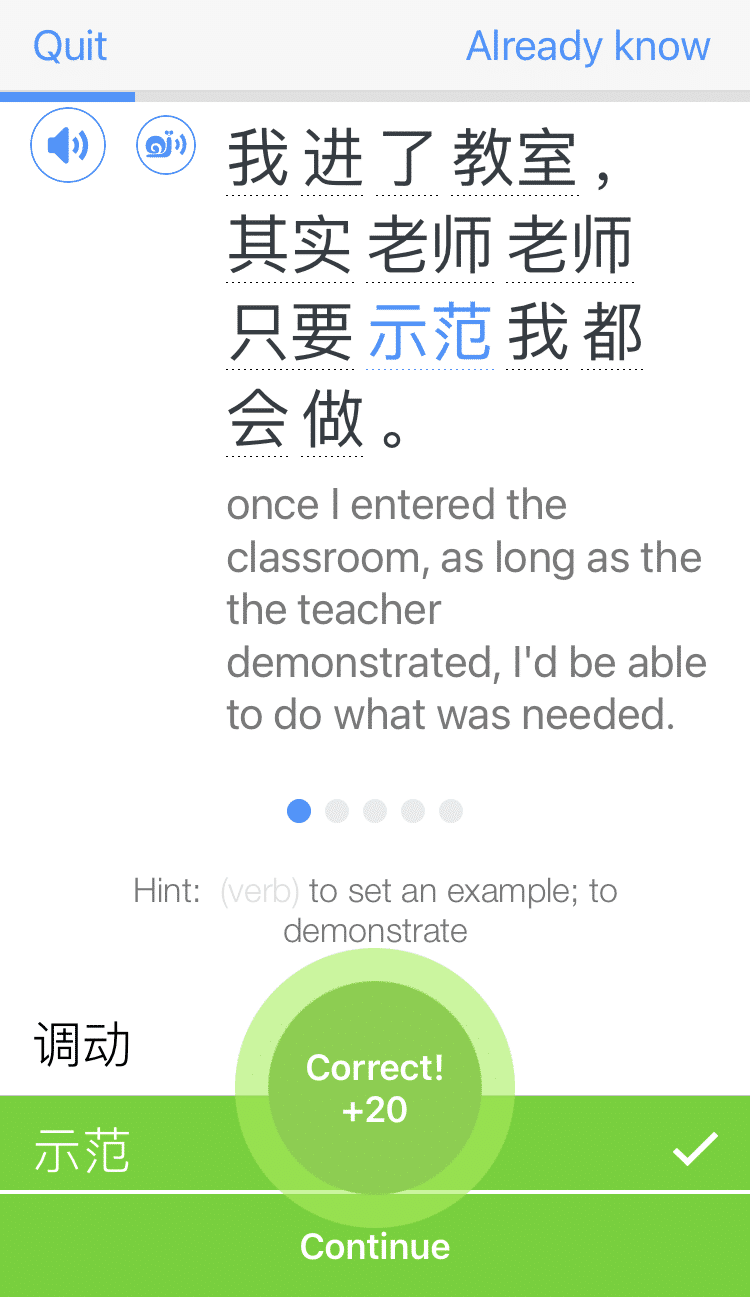

FluentU brings these native Chinese videos within reach via interactive captions. You can tap on any word to instantly look it up. All words have carefully written definitions and examples that will help you understand how a word is used. Tap to add words you'd like to review to a vocab list.

FluentU's Learn Mode turns every video into a language learning lesson. You can always swipe left or right to see more examples for the word you're learning.

The best part is that FluentU always keeps track of your vocabulary. It customizes quizzes to focus on areas that need attention and reminds you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. You have a 100% personalized experience.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)