10 Famous Spanish Poems (with Translations)

Whether you’re a beginner, intermediate or advanced learner, delving into the world of Spanish poems can be a delightful and rewarding experience.

In this post, you’ll discover 10 well-known Spanish poems, organized by skill level so you can easily find exactly where to start.

Plus, I’ll share some tips on how to approach reading poems in Spanish so you can get the most out of them.

So, grab your metaphorical café con leche (coffee with milk), settle in and prepare to be swept away by the magic of Spanish poetry!

Contents

- Spanish Poems for Beginners

- Spanish Poems for Intermediate Learners

- Spanish Poems for Advanced Learners

- Tips for Reading Poems in Spanish

- And One More Thing…

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Spanish Poems for Beginners

Using children’s poetry is a brilliant way to bridge the gap between beginner and intermediate Spanish. Below are three poems by Douglas Wright, a famous writer of children’s poetry from Argentina.

His simple language and construction of imagery as perceived by a child makes it a good starting point for Spanish learners to get their feet wet.

1. “Bien tomados de la mano” (Holding Hands Firmly) by Douglas Wright

This sweet poem about walking hand in hand with someone helps you learn a lot of useful day-to-day vocabulary. Plus, the repetition along with fun, childish imagery makes it very easy to memorize (especially if you break it up into four different sections).

Qué lindo que es caminar,

bien tomados de la mano,

por el barrio, por la plaza,

¿qué sé yo?, por todos lados.

Qué lindo es mirar los árboles,

bien tomados de la mano,

desde el banco de la plaza,

en el que estamos sentados.

Qué lindo es mirar el cielo

bien tomados de la mano;

en nuestros ojos, volando,

dos pájaros reflejados.

Qué lindo que es caminar

bien tomados de la mano;

¡qué lindo, andar por la vida

de la mano bien tomados!

How nice it is to walk,

holding hands firmly,

through the neighborhood, through the plaza,

What do I know?, everywhere.

How nice it is to look at the trees,

holding hands firmly,

from the bench in the plaza,

in which we are sitting.

How nice it is to look at the sky

holding hands firmly;

in our eyes, flying,

two reflected birds.

How nice it is to walk

holding hands firmly;

how nice, to walk through life

with hands held firmly!

2. “Bajo la luna” (Under the Moon) by Douglas Wright

This quick, pretty poem is entirely about appreciating the silence. It begins and opens with the same phrase, meaning “everyone is quiet” and then lists everything that’s quiet on this night. A fun and short one to have stuck in your head!

Todos callados,

bajo la luna;

el bosque, el lago,

el cerro, el monte,

bajo la luna,

todos callados.

Everyone is quiet,

under the moon;

the forest, the lake,

the hill, the mountain,

under the moon,

everyone is quiet.

3. “El brillo de las estrellas” (The Shine of the Stars) by Douglas Wright

This sweet poem about the brilliance of the stars also brings up a couple of words most Spanish beginners probably won’t know, but these will definitely come in handy around the fourth of July (“fireworks: in Spanish are fuegos artificiales).

Mejor que todos los fuegos

que llaman artificiales,

el brillo de las estrellas,

esos fuegos naturales.

Better than all fires

they call artificial,

the shine of the stars,

those natural fires.

Spanish Poems for Intermediate Learners

Once you have some children’s poetry under your belt, you can move on to simple poetry for adults. Don’t feel put off by classic Spanish poetry—much of it is actually very accessible, even when it’s on the longer side! Check out our picks below.

4. “Cancioncilla sevillana” (Seville Song) by Federico García Lorca

Playwright and poet Federico García Lorca was born in the Andalusia region of Spain. He was the son of a wealthy landowner and grew up surrounded by the beauty of the land he loved. The countryside influenced his poetry.

“Cancioncilla Sevillana” draws from nature, but the poet also names a woman, leaving the reader to wonder just exactly what the author had in mind. This poem is short and sweet, which makes it ideal for Spanish language learners.

Amanecía

en el naranjel.

Abejitas de oro

buscaban la miel.

¿Dónde estará

la miel?

Está en la flor azul,

Isabel.

En la flor,

del romero aquel.

(Sillita de oro

para el moro.

Silla de oropel

para su mujer.)

Amanecía

en el naranjel.

Dawn

in the orange grove.

Golden bees

were looking for honey.

Where could it be,

the honey?

It’s in the blue flower,

Isabel.

In the flower,

of that rosemary.

(Gold chair

for the Moor.

Tinsel chair

for his wife.)

Dawn

in the orange grove.

5. “Viento, agua, piedra” (Wind, Water, Stone) by Octavio Paz

Octavio Paz was a Mexican poet and essayist who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1990. “Viento, agua, piedra” (“Wind, water, stone”) speaks to the way that all is connected and beautifully paints a picture of how humans, nature and situations impact each other.

A Roger Caillois

El agua horada la piedra,

el viento dispersa el agua,

la piedra detiene al viento.

Agua, viento, piedra.

El viento esculpe la piedra,

la piedra es copa del agua,

el agua escapa y es viento.

Piedra, viento, agua.

El viento en sus giros canta,

el agua al andar murmura,

la piedra inmóvil se calla.

Viento, agua, piedra.

Uno es otro y es ninguno:

entre sus nombres vacíos

pasan y se desvanecen

agua, piedra, viento.

For Roger Caillois

The water has hollowed the stone,

the wind dispersed the water,

the stone stopped the wind.

Water, wind, stone.

The wind sculpts the stone,

the stone is a cup of water,

the water runs off and is wind.

Stone, wind, water.

The wind sings in its turnings,

the water murmurs as it goes,

the immovable stone is quiet.

Wind, water, stone.

One is the other and is neither:

Among their empty names

they pass and disappear

water, stone, wind.

6. “Oda a los calcetines” (Ode to My Socks) by Pablo Neruda

Pablo Neruda was a Chilean poet who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1971. In “Oda a los calcetines”(“Ode to My Socks”), he compares a pair of socks he’s been gifted to many things, taking you on an image-filled journey.

You might feel intimidated by the length, but the story-telling nature makes it easy to follow. It’s one of my favorite poems, and one of the first I learned to recite.

Me trajo Maru Mori

un par de calcetines

que tejió con sus manos de pastora,

dos calcetines suaves como liebres.

En ellos metí los pies

como en dos estuches

tejidos con hebras del

crepúsculo y pellejo de ovejas.

Violentos calcetines,

mis pies fueron dos pescados de lana,

de azul ultramarino

atravesados por una trenza de oro,

dos gigantescos mirlos,

dos cañones;

mis pies fueron honrados de este modo

por estos celestiales calcetines.

Eran tan hermosos que por primera vez

mis pies me parecieron inaceptables

como dos decrépitos bomberos,

bomberos indignos de aquel fuego bordado,

de aquellos luminosos calcetines.

Sin embargo resistí la tentación

aguda de guardarlos como los colegiales

preservan las luciérnagas,

como los eruditos coleccionan

documentos sagrados,

resistí el impulso furioso de ponerlos

en una jaula de oro y darles cada

día alpiste y pulpa de melón rosado.

Como descubridores que en la selva

entregan el rarísimo venado verde

al asador y se lo comen con remordimiento,

estiré los pies y me enfundé

los bellos calcetines y luego los zapatos.

Y es ésta la moral de mi Oda:

dos veces es belleza la belleza,

y lo que es bueno es doblemente bueno,

cuando se trata de dos calcetines

de lana en el invierno.

Maru Mori brought me

a pair of socks

that she knitted herself with her sheepherder’s hands,

two socks as soft as rabbit fur.

Into them I slipped my feet

as though into two cases

knit with thread of

twilight and sheepskin.

Violent socks,

my feet were two fish made of wool,

two large sharks

of sea-blue

crossed by one golden thread,

two immense blackbirds,

two cannons;

my feet were honored in this way

by these heavenly socks.

They were so beautiful that for the first time

my feet seemed to me unacceptable

like two decrepit firemen,

firemen unworthy of that woven fire,

of those glowing socks.

Nevertheless, I resisted the sharp temptation

to save them somewhere as schoolboys

keep fireflies,

as learned men collect

sacred texts,

I resisted the mad impulse to put them

into a golden cage and give them every

day birdseed and pink melon flesh.

Like explorers in the jungle

who hand over the very rare green deer

to the spit and eat it with remorse,

I stretched out my feet and pulled on

the magnificent socks and then my shoes.

And this is the moral of my Ode:

beauty is twice beauty,

and what is good is doubly good,

when it is a matter of two socks

made of wool in winter.

7. “Soneto XVII” (Sonnet XVII) by Pablo Neruda

Here’s another one by Pablo Neruda. This is one of the most celebrated poems in his collection “Cien sonetos de amor” (One Hundred Love Sonnets). In it, he expresses his love for someone in a unique way, claiming that it’s simple and direct yet also secretive.

No te amo como si fueras rosa de sal, topacio

o flecha de claveles que propagan el fuego:

te amo como se aman ciertas cosas oscuras,

secretamente, entre la sombra y el alma.

Te amo como la planta que no florece y lleva

dentro de sí, escondida, la luz de aquellas flores,

y gracias a tu amor vive oscuro en mi cuerpo

el apretado aroma que ascendió de la tierra.

Te amo sin saber cómo, ni cuándo, ni de dónde,

te amo directamente sin problemas ni orgullo:

así te amo porque no sé amar de otra manera,

sino así de este modo en que no soy ni eres,

tan cerca que tu mano sobre mi pecho es mía,

tan cerca que se cierran tus ojos con mi sueño.

I love you as if you were a rose of salt, topaz,

or arrow of carnations that propagate fire:

I love you as certain dark things are loved,

secretly, between the shadow and the soul.

I love you as the plant that doesn’t flower and carries

hidden within itself the light of those flowers,

and thanks to your love, darkly in my body

the tight aroma that arose from the earth lives on.

I love you without knowing how, or when, or from where,

I love you directly without complexities or pride:

so I love you because I don’t know any other way to love,

except this way in which I am not nor are you,

so close that your hand on my chest is mine,

so close that your eyes close with my dreams.

Spanish Poems for Advanced Learners

In addition to improving your language skills, more complex poetry is also a great way to advance your interest in different areas of Latin American culture. Many poems in Spanish denote the author’s preoccupations with events or themes in their home country.

8. “Cultivo una rosa blanca” (I Cultivate a White Rose) by José Martí

This poem by Cuban poet José Martí has a repetitive element, but there’s a lot to dig into. Deceptively complex but still short and easy to memorize, this is a good poem to get you deeper into the language.

Cuba has long been rife with churning political waters, and this author’s politician/writer combination will appeal to history buffs. As a writer, Martí is heralded as one of the fore-founders of Modernist literature in Latin America.

Cultivo una rosa blanca

en junio como enero

para el amigo sincero

que me da su mano franca.

Y para el cruel que me arranca

el corazón con que vivo,

cardo ni ortiga cultivo;

cultivo la rosa blanca.

I cultivate a white rose

in June and January

for the true friend

who gives me his sincere hand.

And for the cruel one who rips out

the heart with which I live,

I don’t cultivate the thistle or the nettle;

I cultivate the white rose.

9. “Desde mi pequeña vida” (From My Small Life) by Margarita Carrera

This powerful poem reflects on the injustice suffered by many people in Guatemala during the Civil War. The author talks about those who died defending an ideal, in contrast to her small, insignificant life where she feels like she can’t make much of a difference.

Margarita Carrera was born in the late 1920s, and her writing has tons of historical relevance as she was the first woman to graduate from the University of San Carlos of Guatemala.

Desde mi pequeña vida

te canto

hermano

y lloro tu sangre

por las calles derramada

y lloro tu cuerpo

y tu andar perdido.

Ahora estoy aquí

de nuevo contigo

hermano.

Tu sangre

es mi sangre

y tu grito se queda

en mis pupilas

en mi cantar mutilado.

From my small life

I sing to you

brother

and I cry your blood

shed in the streets

and I cry your body

and your lost walk.

Now I am here

again with you

brother.

Your blood

is my blood

and your scream stays

in my pupils

in my mutilated singing.

10. “Walking around” by Pablo Neruda

“Walking Around” is a more advanced poem by Pablo Neruda that talks about a man who seems to be going around normally about his everyday life. Deep down, though, he’s feeling intense anger and despair about what it’s like to be human in modern times.

These are only the first three stanzas of the poem, but you can read the whole thing at the link above.

Sucede que me canso de ser hombre.

Sucede que entro en las sastrerías y en los cines

marchito, impenetrable, como un cisne de fieltro

navegando en un agua de origen y ceniza.

El olor de las peluquerías me hace llorar a gritos.

Sólo quiero un descanso de piedras o de lana,

sólo quiero no ver establecimientos ni jardines,

ni mercaderías, ni anteojos, ni ascensores.

Sucede que me canso de mis pies y mis uñas

y mi pelo y mi sombra.

Sucede que me canso de ser hombre.

It so happens I am sick of being a man.

And it happens that I walk into tailor shops and movie houses

dried up, waterproof, like a swan made of felt

steering my way in a water of wombs and ashes.

The smell of barbershops makes me break into hoarse sobs.

The only thing I want is to lie still like stones or wool,

the only thing I want is to see no more stores, no gardens,

no more goods, no spectacles, no elevators.

It so happens that I am sick of my feet and my nails

and my hair and my shadow.

It so happens I am sick of being a man.

Tips for Reading Poems in Spanish

Poetry can be difficult to interpret even in your native language, so it’s completely understandable if these poems feel overwhelming to you. Here are my tips for making them more digestible:

- Start small. Beginning with children’s poetry primes you for the different tenses and structures of poems in Spanish. Children’s poems utilize simple repetition and literal imagery, so they’re great for building your vocabulary. They can be used as a strong stepping-stone to reading and understanding more complex poetry in Spanish.

- Read aloud. Reading aloud will help with your general speaking ability because speaking Spanish is really the only way to get better at it! As speaking is often the element language learners struggle with the most, you’ll be ahead of the game if you take a deep breath and practice out loud.

- Put the poem where you’ll see it. What’s the point of working to pronounce a poem if you’re just going to forget what you’ve read? By printing out little copies of each poem and sticking them in places you’ll be sure to see them (think: mirrors, doors, refrigerators), both the poem and the Spanish will stay in your mind for the long term.

- Write it out from memory. Once you’re familiar with the poem, take a pad of paper and try to write it from memory. This can be a good gauge to see if you’ve really learned what the words mean. Maybe you forget a word part-way through but fill in the correct one based on the rhyme or theme of the poem.

- Have some tools on hand to help you. There are plenty of places to find learning tools online. To start with, it’s helpful to keep translation apps or dictionaries on hand. Check out some of our recommendations for flashcard apps as well, or do some exploration of the app stores on your own.

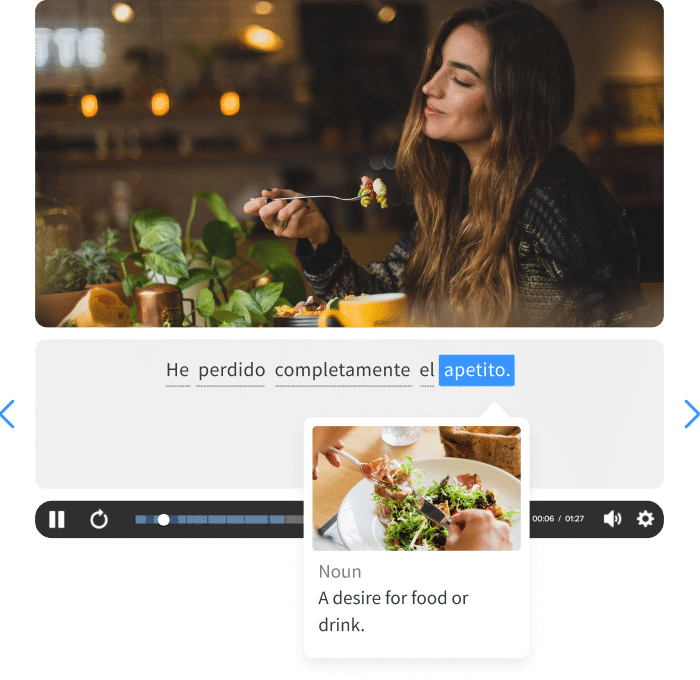

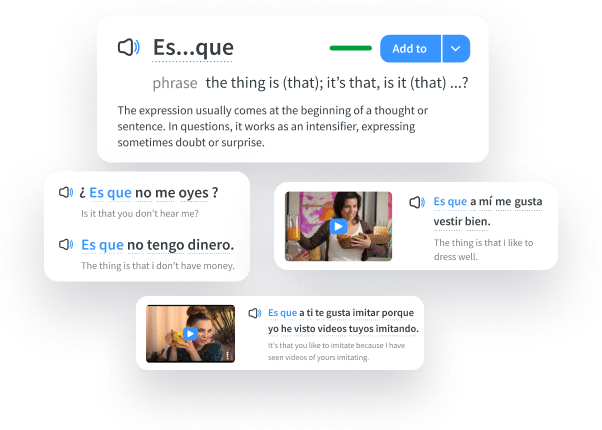

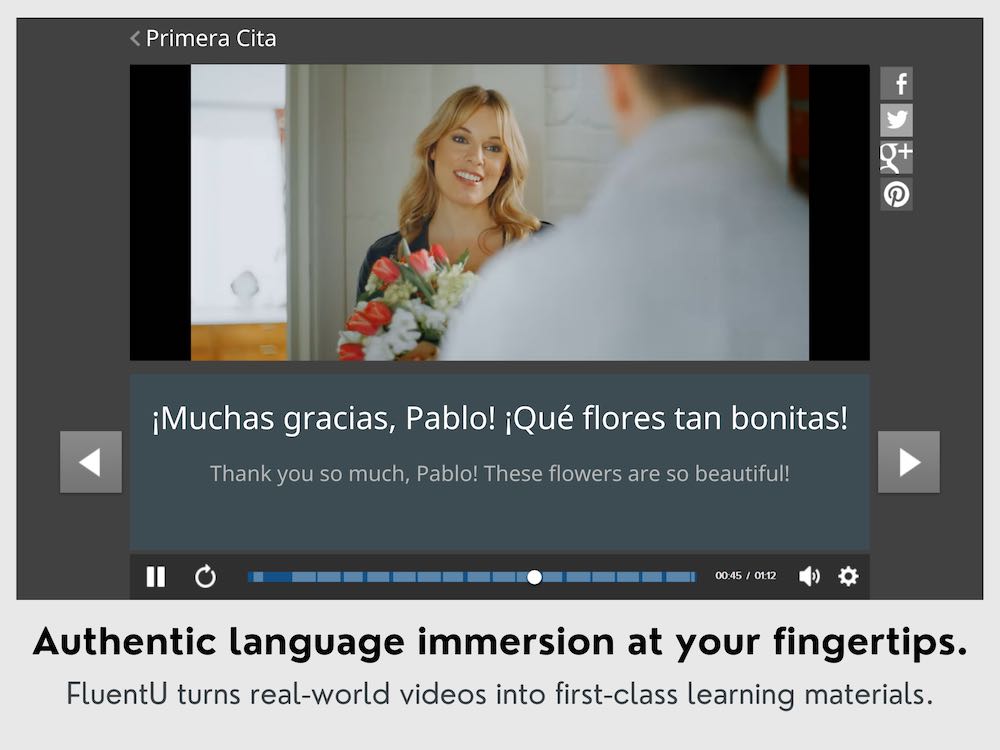

For a more diverse resource, there’s FluentU, which lets you see Spanish words in context through Spanish videos.

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Once you’ve got some inspiration from these Spanish poems, you can try writing your own.

Who knows? You might be the next Douglas Wright or Pablo Neruda!

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing…

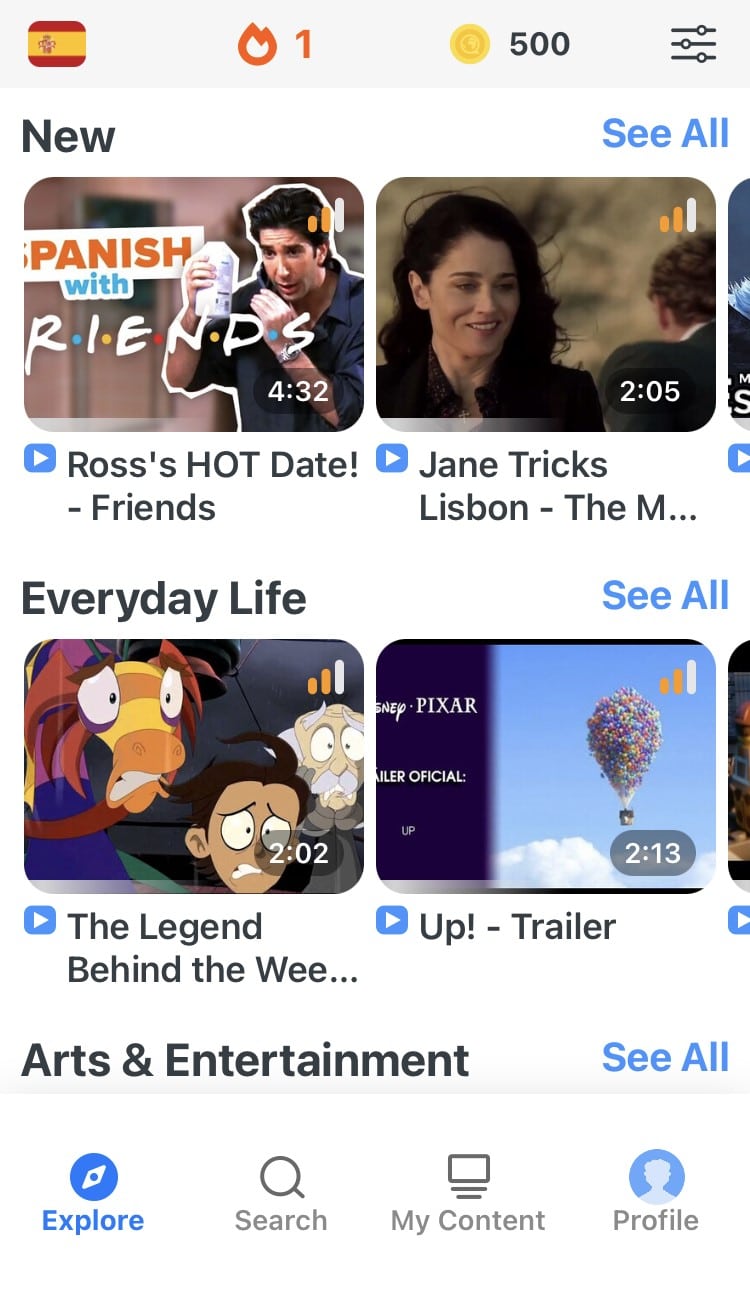

If you've made it this far that means you probably enjoy learning Spanish with engaging material and will then love FluentU.

Other sites use scripted content. FluentU uses a natural approach that helps you ease into the Spanish language and culture over time. You’ll learn Spanish as it’s actually spoken by real people.

FluentU has a wide variety of videos, as you can see here:

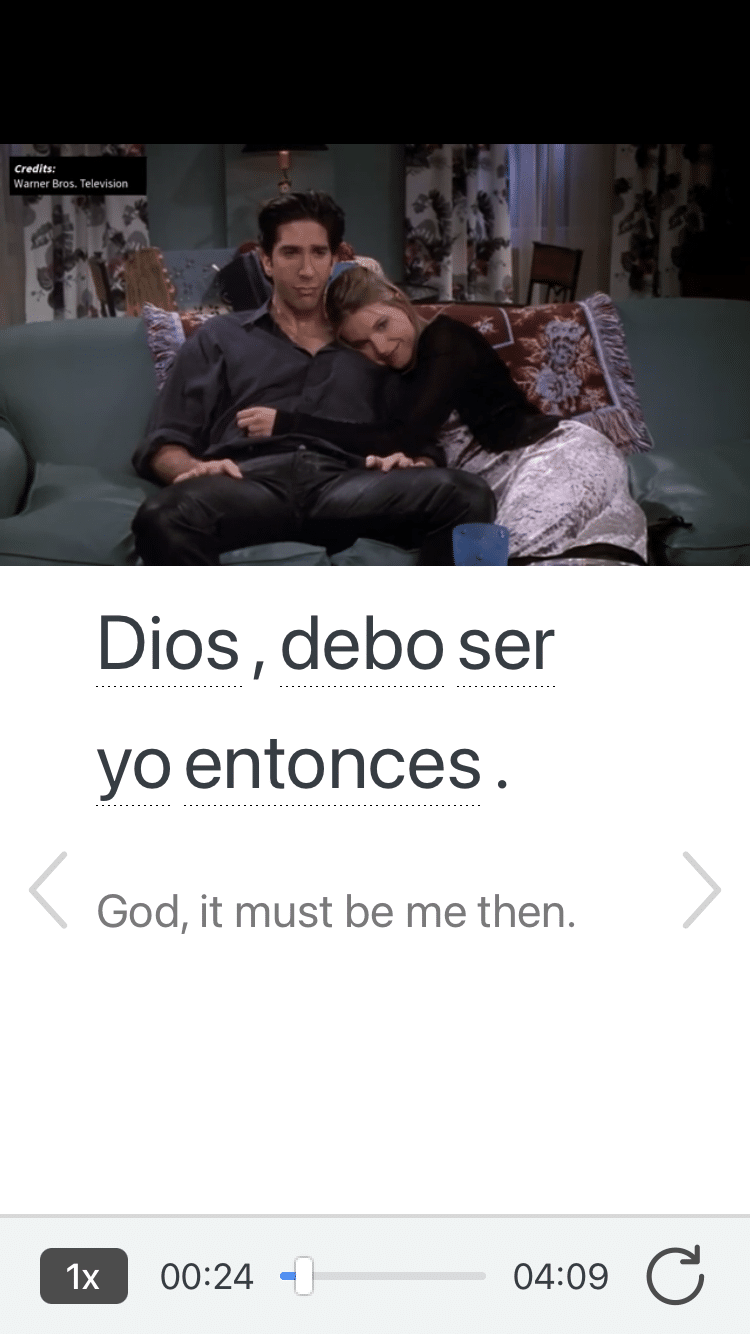

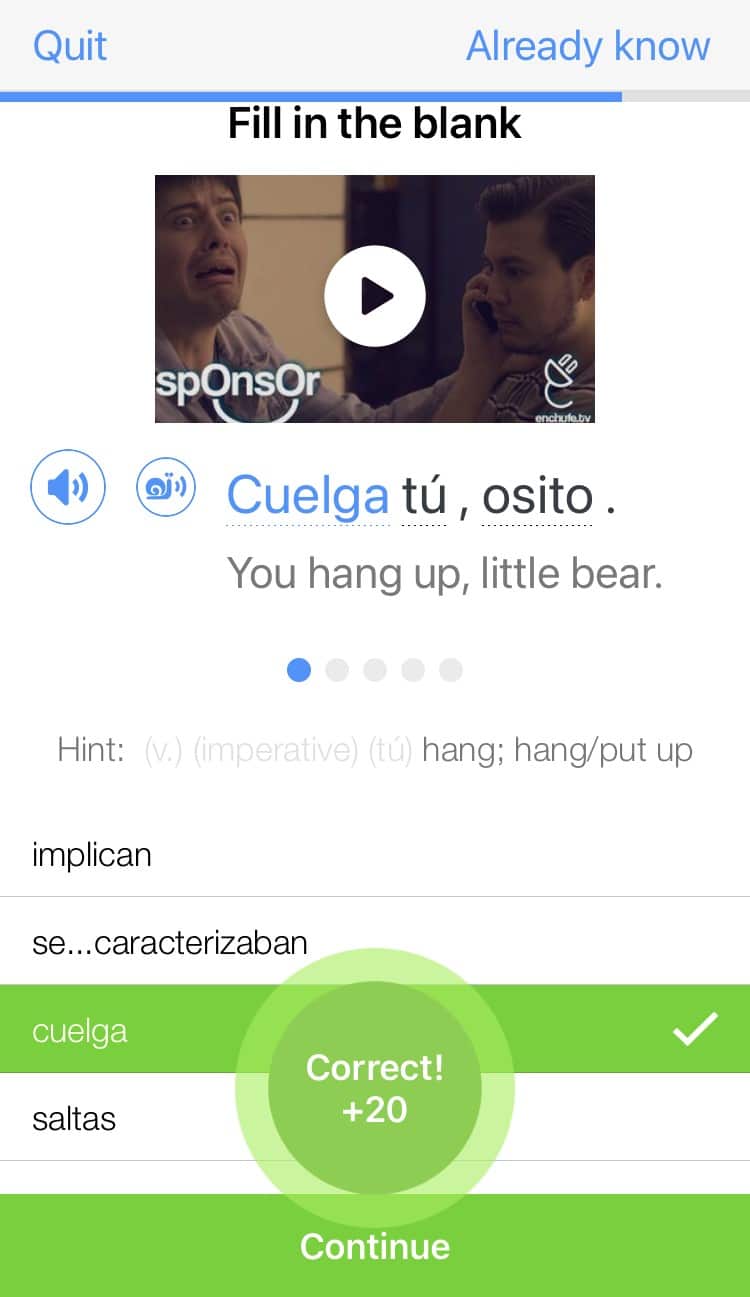

FluentU brings native videos within reach with interactive transcripts. You can tap on any word to look it up instantly. Every definition has examples that have been written to help you understand how the word is used. If you see an interesting word you don’t know, you can add it to a vocab list.

Review a complete interactive transcript under the Dialogue tab, and find words and phrases listed under Vocab.

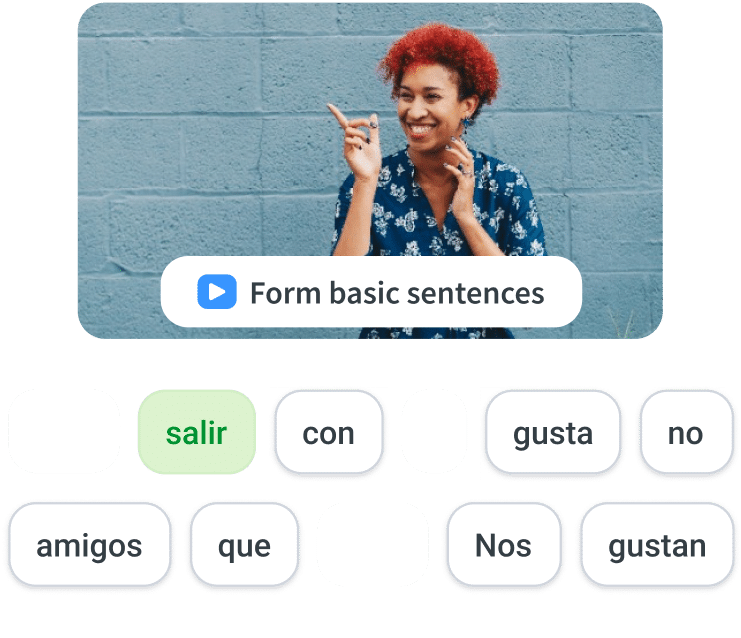

Learn all the vocabulary in any video with FluentU’s robust learning engine. Swipe left or right to see more examples of the word you’re on.

The best part is that FluentU keeps track of the vocabulary that you’re learning, and gives you extra practice with difficult words. It'll even remind you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. Every learner has a truly personalized experience, even if they’re learning with the same video.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)