9 Fantastic Free Japanese Learning Apps to Learn Japanese Today

Japanese language apps are the newest way to learn Japanese on your own time for free.

Using language learning apps is a fantastic way to learn the language whether you’re a beginner or an advanced learner.

In this post, you’ll find a list of free Japanese learning apps best for various learning needs and preferences so you can easily choose the one for you.

Contents

- Best Free Japanese Learning Apps

- 1. Best Overall: Duolingo

- 2. Best For Beginners: LingoDeer

- 3. Best For Video Game Based Learning: Mondly

- 4. Best For Learning Specific Topics: Learn Japanese Free (WingsApp)

- 5. Best For Visual Learners: Infinite Japanese

- 6. Best For Learning Vocabulary: Memrise

- 7. Best For Learning Writing and Reading: Write It! Japanese

- 8. Best For All Levels Learners: Bravolol Japanese

- 9. Best For Advanced Learners: Obenkyo

- Tips for Using Japanese Language Apps

- And One More Thing...

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Best Free Japanese Learning Apps

1. Best Overall: Duolingo

Access on: Web | iOS | Android

Is it really possible to learn Japanese in just five minutes a day? Duolingo sure thinks so, and it looks like they deliver.

Many people give up on learning a new language because they just can’t find the time to study. Duolingo focuses on light, quick lessons that you can take during your work break, on your commute home or whenever you can find just a few free minutes.

Duolingo is available for both Apple and Android devices, and it’s one of the few apps on our list that doesn’t charge for special features (the only charge is if you want to go commercial-free). The app’s creators are dedicated to free language learning for any level.

2. Best For Beginners: LingoDeer

Access on: Web | iOS | Android

This app aims to improve your Japanese level in just 21 days. It uses cute, interactive animations and features lesson plans designed by experienced Japanese teachers.

Each lesson is split into bite-sized chunks which teach vocabulary, writing and sentence structure through repetition and various types of questions. Words and entire sentences are paired with clear audio which can be slowed down for better understanding.

LingoDeer is available for Android and iOS devices and can be useful for all Japanese levels, though beginners will benefit the most from this app.

3. Best For Video Game Based Learning: Mondly

Turning something educational into a video game can make one more inclined to learn. At least, that’s the idea Mondly has based their language app around.

The more lessons you complete, the further you make it on the app’s map. The lessons mix kanji and spoken Japanese together so you can get a full education in a condensed package. Think Rosetta Stone but with a more goal-oriented spin.

The free version has plenty of content to keep you busy learning but you can also purchase a premium subscription, which includes benefits like exclusive lessons, modules and conversations.

4. Best For Learning Specific Topics: Learn Japanese Free (WingsApp)

Access on: Android

Instead of forcing you to adhere to a pre-designed lesson plan, this app allows you to pick and choose what you want to learn every time you use it.

Greetings, travel, love, friendship, food: You get to decide the topic you want to cover. And with over 65 topics to choose from, containing a huge total of 5000+ phrases and words to learn, you’ll always find something to interest you.

Beginner and intermediate learners will appreciate the vocabulary lookup options.

5. Best For Visual Learners: Infinite Japanese

If you’re a visual learner, Infinite Japanese will be right up your alley.

This app focuses on learning Japanese the “natural” way with absolutely no English. Instead, graphics help you associate Japanese words with their meanings.

There are six difficulty modes, so every kind of learner can benefit from this app.

The free portion of the app contains plenty of material but to get access to the many locked lessons you’ll need to pay for premium features through in-app purchases.

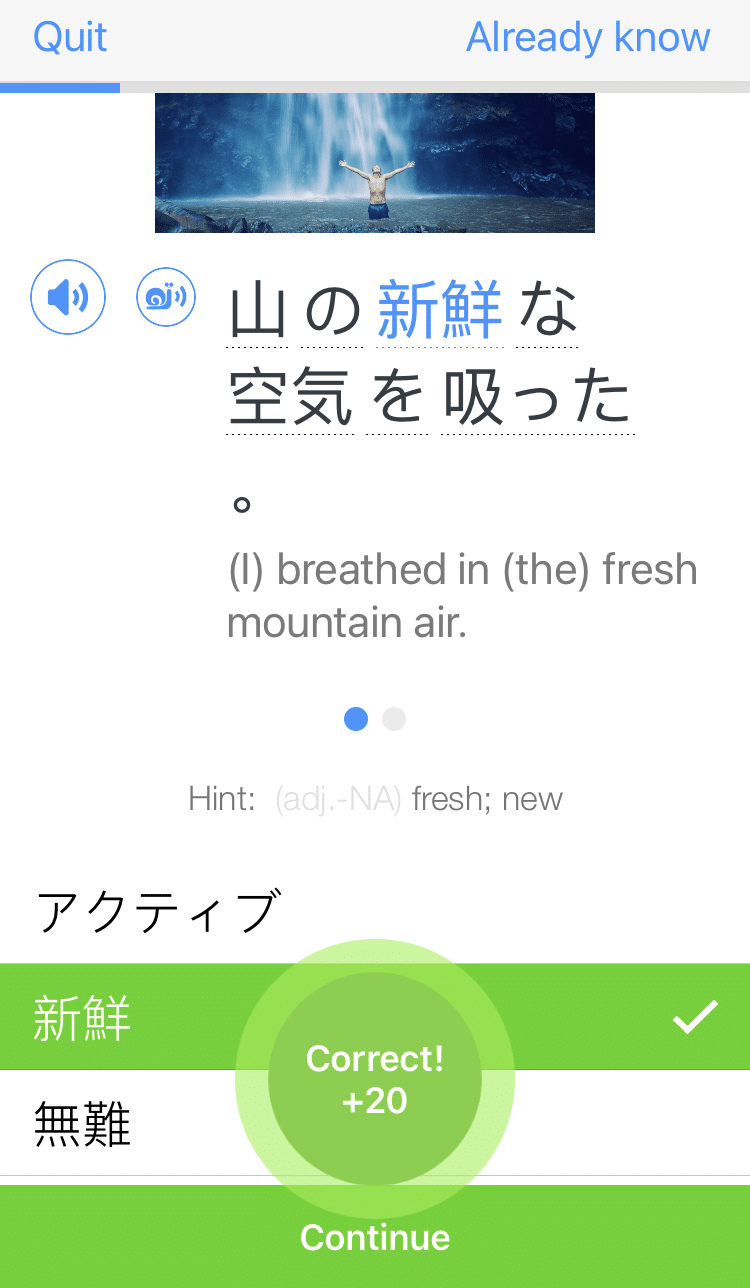

6. Best For Learning Vocabulary: Memrise

Access on: Web | iOS | Android

Like Infinite Japanese, Memrise takes a more visual approach to learning the language. Full of fun animations and set up very much like a video game, Memrise makes learning Japanese fun.

Like Infinite Japanese, Memrise takes a more visual approach to learning the language. Full of fun animations and set up very much like a video game, Memrise makes learning Japanese fun.

Memrise is primarily a vocabulary-learning app, with many different lists available to study from. The app uses repetition to perfect your memory of a word or phrase, which is then reinforced with frequent reminders of already-learned words. User-submitted visual and text mnemonic devices make it easier to remember certain words, and you can customize just how much you want to learn per day.

Memrise has a Beginner mode and an Advanced mode. The Pro version boasts perks like speed review, video stats and more.

7. Best For Learning Writing and Reading: Write It! Japanese

Access on: Android

If you’re an intermediate or advanced learner who wants to focus on writing and reading kanji and katakana, Write it! Japanese might just be what you’re looking for.

The smooth interface of this app is super user-friendly and focuses on stroke order, vocabulary and grammar. You can even build your own customizable tests.

8. Best For All Levels Learners: Bravolol Japanese

This app is geared towards all levels of language learners. Like WingsApp’s Japanese language app, you can pick and choose what you want to learn at any given time.

What really sets this app apart from the rest is its “snail” mode. If you’re having trouble keeping up with Japanese pronunciation, clicking the little snail next to each lesson slows the audio down.

The free version runs on ads, which can sometimes get intrusive. The premium version is ad-free.

9. Best For Advanced Learners: Obenkyo

Access on: Android

This app focuses on writing and reading Japanese characters. It’s also a fantastic Japanese dictionary to have on hand when you need to know what a romaji, kanji or hiragana word means. You can also build your own tests and flashcards to aid in your studies.

Since this app focuses mostly on stroke order and written Japanese, it would be ideal for intermediate or advanced learners.

Tips for Using Japanese Language Apps

The apps we recommend are pretty easy to use but we want to make sure you can benefit from them fully, so here are a few tips:

- Check your language app daily. Set notifications for lessons if the app contains such a feature, or add a reminder in your own daily calendar. Be consistent and be sure to schedule app time for when you aren’t busy and can find a quiet space to focus.

- Try using more than one app. Not every app on this list is ideal for every learner. Do some “app shopping” and test each option to find out which one works best for you. Since each app has different features, consider using two at once to reinforce your learning.

- Supplement with an outside class. These apps work wonderfully on their own, but the added aid of a class, online course or other Japanese language learning method will only improve your chances of achieving fluency.

- Check out apps with free trials. Free trials give you a good understanding of how certain apps work. As you learn, you may want to broaden your horizons and build a budget for learning. For example, the Lingvist app offers a free trial to test out their wonderful flashcard system.

While free apps are a great way to learn a language, language programs can complement these and help you to improve quicker.

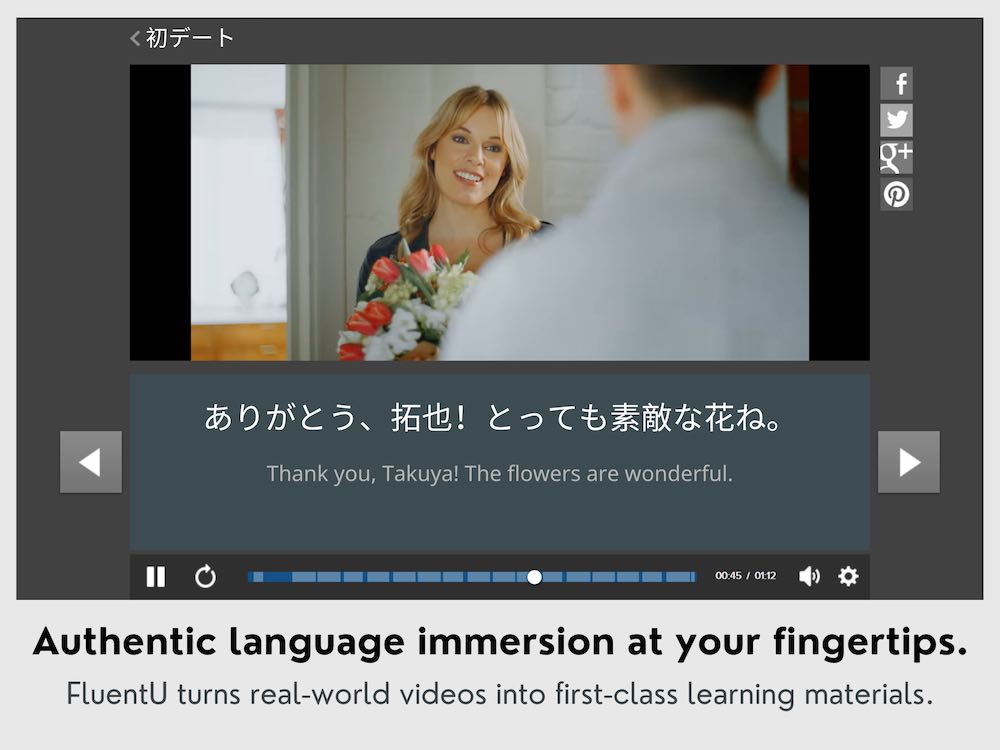

There are a lot of programs out there, like FluentU. This program gives you access to hundreds of Japanese videos with interactive captions.

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Who knew there were so many awesome language apps to choose from?

Learning Japanese has never been easier than it is today, with free apps! We suggest downloading all of them to test which ones work the best for your personal learning needs.

Good luck on your language journey and don’t forget to 勉強頑張ってね! (べんきょう がんばってね!)—study your hardest!

And One More Thing...

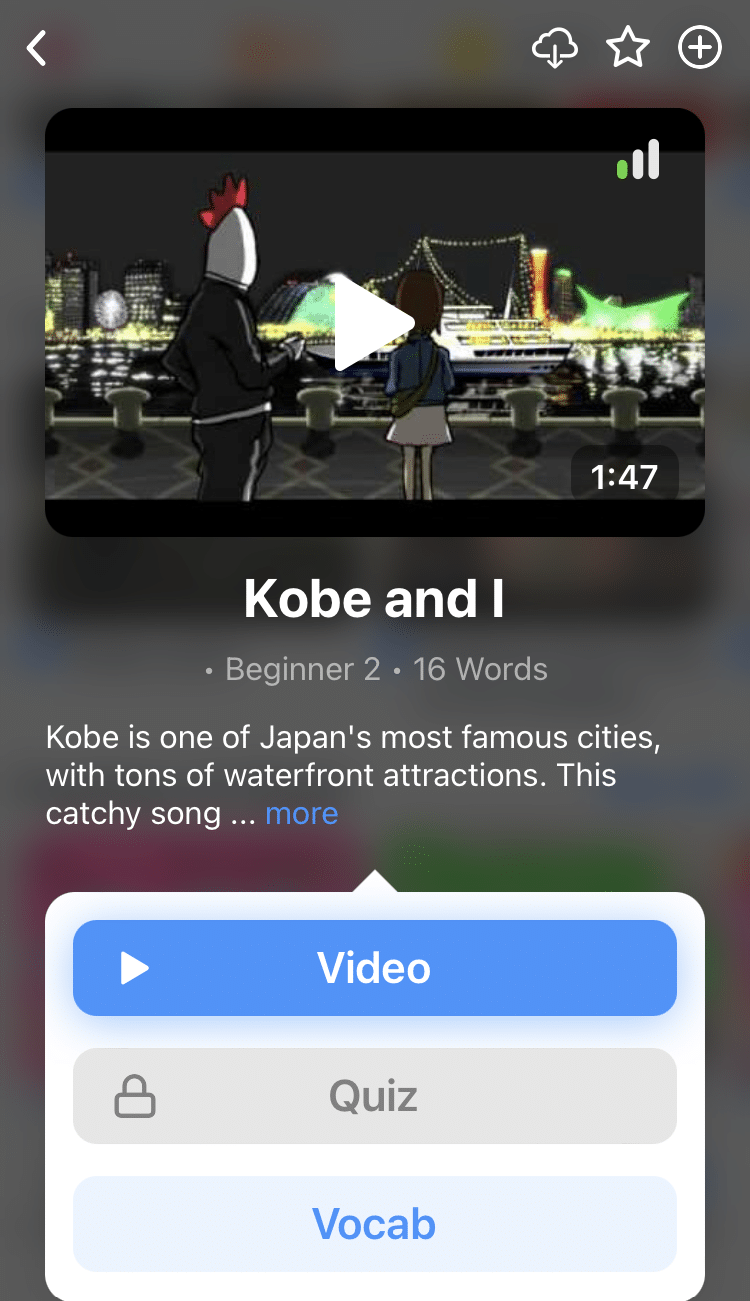

If you love learning Japanese with authentic materials, then I should also tell you more about FluentU.

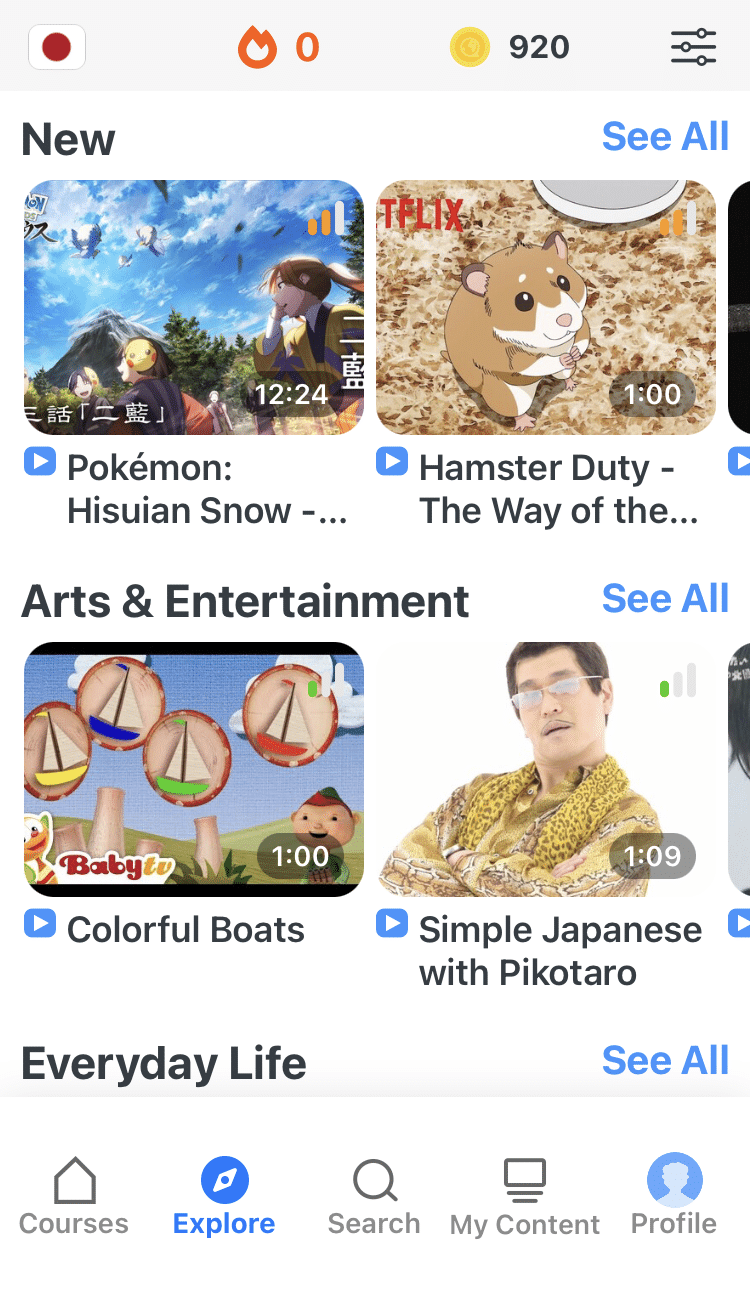

FluentU naturally and gradually eases you into learning Japanese language and culture. You'll learn real Japanese as it's spoken in real life.

FluentU has a broad range of contemporary videos as you'll see below:

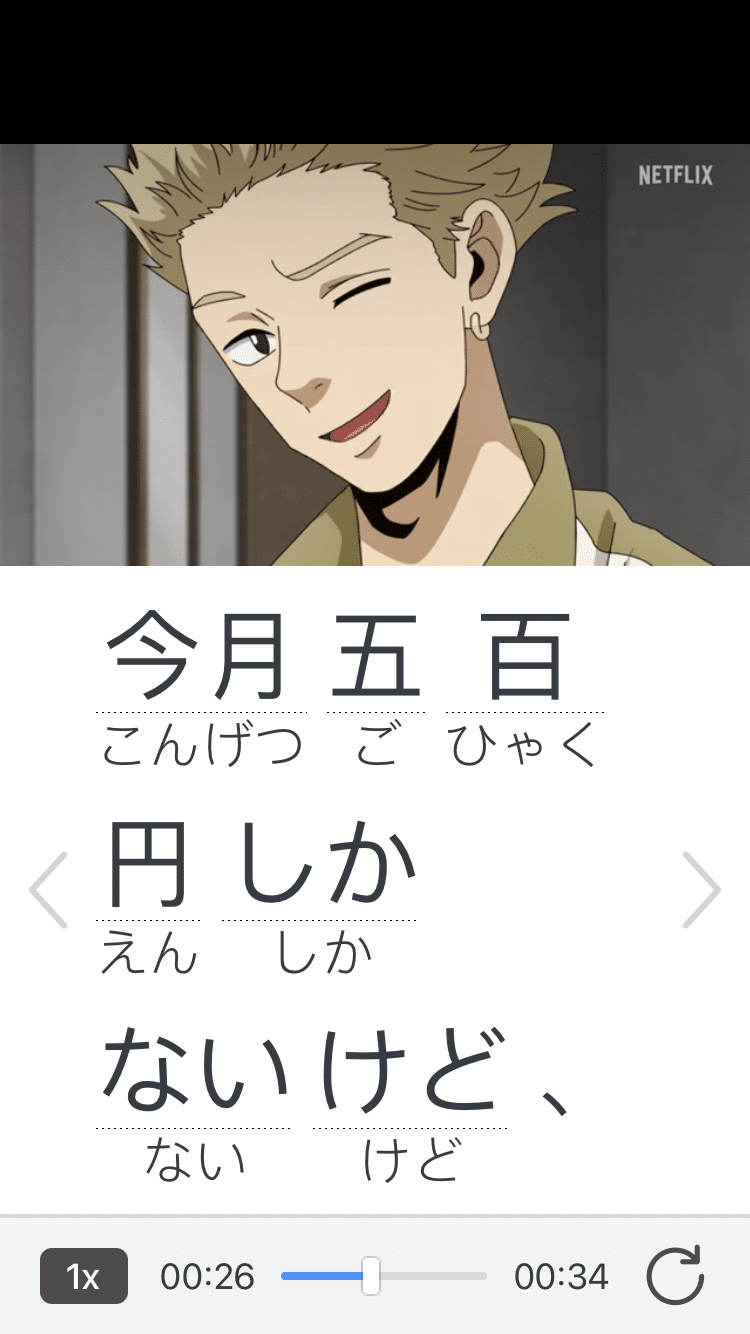

FluentU makes these native Japanese videos approachable through interactive transcripts. Tap on any word to look it up instantly.

All definitions have multiple examples, and they're written for Japanese learners like you. Tap to add words you'd like to review to a vocab list.

And FluentU has a learn mode which turns every video into a language learning lesson. You can always swipe left or right to see more examples.

The best part? FluentU keeps track of your vocabulary, and gives you extra practice with difficult words. It'll even remind you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. You'll have a 100% personalized experience.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)