3 Simple Uses of Zu in German

Let’s talk about a two-letter word that’s incredibly versatile: the German preposition zu .

By itself, the word expresses direction towards someone or something.

But paired up with other words, it has tons of other possibilities.

So the next time you’re playing (German) Scrabble, don’t worry if you only have “z” and “u” left!

Contents

- Why Focus on Zu?

- How to Form Contractions with Zu

- A Word of Many Meanings: How to Use the German Word Zu

- And One More Thing...

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Why Focus on Zu?

Think about the words you use all the time in your mother tongue. Can you list a few?

You’ve probably included words that describe your daily life (like I, you and me) and probably a few verbs, too. You need those verbs to tell others what you had for breakfast, what happened to you on the way to work or what happened at school that day. Most German native speakers will have a similar list of common words, since we all share basic needs.

Remember sein (to be) and haben (to have)? Those verbs are essential to the German language as (1) basic statements about the state of something or what someone has; and (2) as helping verbs.

Learning zu is the next step in building your German language foundation.

It’s not necessarily a word you’ll use everyday, but it’s one you’ll see often. It’s also a very versatile word, so learning the different meanings of zu and how it works is crucial to expressing yourself fluently in a variety of situations.

How to Form Contractions with Zu

Before we dive into our zu guide below, we’ll need to cover German contractions so you can recognize how the word is used in different example sentences.

Since zu is a dative preposition, we need to select the correct dative article for our noun. Then, we then take the last letter of the new article (m, r, m) and add that on to the end of zu, like so:

| Type of Noun | Dative Article | Zu Phrases | Contractions of Zu Phrases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Masculine | dem | zu dem | zum |

| Feminine | der | zu der | zur |

| Neuter | dem | zu dem | zum |

(For a comprehensive rundown or refresher on German articles for different genders and cases, the University of Michigan has a helpful chart.)

This is also a handy way to figure out the gender of a noun you don’t know. If you see zur, you’ll know that the noun following is feminine. Likewise, nouns following zum are either masculine or neuter.

These can be difficult concepts to master, so it’s best to get a lot of practice with them through exposure. Seeing how native speakers use zu and other grammar concepts in real conversations is a great way to build your understanding of them.

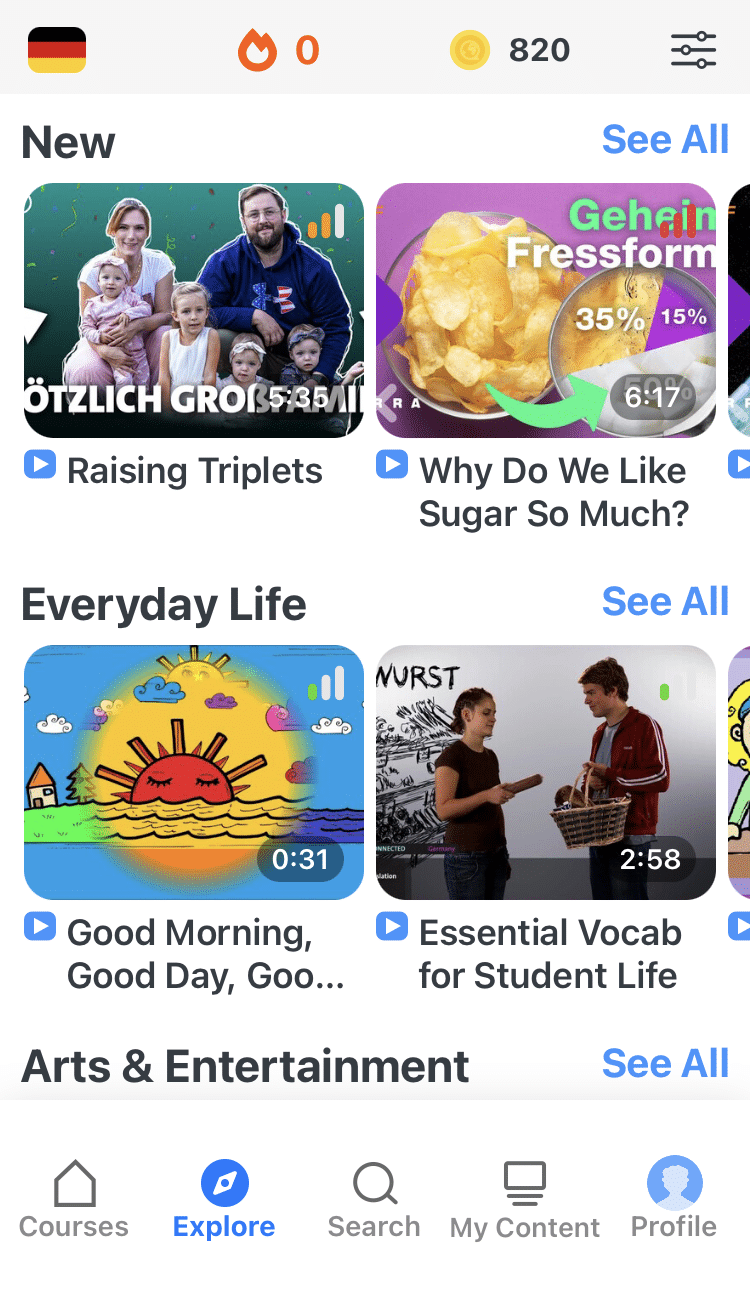

You can see these concepts in action by watching native German speakers on FluentU.

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

The program sorts videos by difficulty and subject matter, so you can easily find videos that feature the words and grammar you want to review.

Zu is only two letters long, but it deserves a lot of study and practice. Once you really learn how it can work in different contexts, you can make some pretty versatile German sentences.

A Word of Many Meanings: How to Use the German Word Zu

1. When Zu Means “To” or “Towards”

One of the most common forms of zu is the dative preposition. In this context, it means “to” or “towards” something or someone, and it changes the case of the following noun to dative.

Let’s look at a few examples:

| German Sentence With Zu | English Translation | Literal Translation |

|---|---|---|

| Kommst du zur Party? | Are you coming to the party? | Come you to the party? |

| Wir fahren mit dem Auto zum Supermarkt. | We're driving to the grocery store. | We travel with the car to the supermarket. |

| Sie rennen zum Bahnhof. | They run to the train station. | They run to the train station. |

| Ich fahre dieses Wochenende zu meiner Tante. | I'm going to my aunt's this weekend. | I travel this weekend to my aunt. |

Zu is sometimes confused with nach , which usually indicates a more distant destination or direction:

- Nächste Woche fahre ich nach München. (Next week, I’m travelling to Munich.

- Wir gehen zum Supermarkt. (We go to the supermarket.)

This one’s a bit confusing, because Germany and the supermarket are both destinations, technically. But a helpful rule of thumb is to think of the distance. Zu tends to be appropriate for locations that are closer to you, whereas nach is appropriate for locations that are farther away. Think about it like walking somewhere versus having to fly or drive for several hours.

It’s important to keep in mind, however, that prepositions are notorious for having numerous exceptions, where the reasoning for using one over the other is often just “because that’s the way it is.”

For example, you might expect to see zu when saying “to go home”, but zu Hause actually means you’re already “at home”—no journey needed. “To go home” is actually a set phrase using nach—nach Hause—however far away you are from your abode.

There are also a lot of locations that you tend to use the preposition in for, like ins Kino (to the movie theater). So sometimes, you just need to learn what preposition is used through experience.

These patterns and rules are still immensely useful when trying to figure out which preposition to use if you’re stuck though! So note them down!

2. When Zu Expresses Causes or Conditions

For this usage of zu, we’ll need to create infinitive constructions. These are basically a fancy way to express cause or condition.

For example, in order to become fluent in German, you’ll have to study grammar. You can’t speak German without knowing how to conjugate verbs, and instead of speaking in English all the time, you should speak in German more often to get practice.

Below are the German infinitive constructions with zu you should know. These constructions use the infinitive of a verb, much like modals do, but are set off by a comma. You’ll place the verb after zu, and the rest of your phrasing between zu and um, ohne or (an)statt.

For example:

| German Infinitive Constructions With Zu | Example Sentence | English Translation |

|---|---|---|

| um... zu in order to | Ich fahre nach Frankfurt,um meine Mama zu besuchen. | I'm travelling to Frankfurt to visit my mom. |

| ohne... zu without | Sie haben das Restaurant verlassen, ohne die Rechnung zu bezahlen | They left the restaurant without paying the bill. |

| (an)statt... zu instead of | Anstatt ihre Hausaufgaben zu machen, spielt sie mit ihren Freunden. | Instead of doing her homework, she plays with her friends. |

3. When Zu Is Used in Infinitive Clauses

For this usage, zu is combined with the infinitive in dependent clauses where the subject is the same as the first clause.

- Nina versucht, ihre Hausaufgaben zu machen. (Nina tries to do her homework.)

“Nina” is the subject in both clauses, so here we need to use zu before the infinitive.

Zu and the infinitive is also used for impersonal expressions, where there is no subject in at all in the second clause:

- Es ist schön, mit dir zu reden. (It’s nice to talk to you.)

So how do you form this? With inseparable verbs, it’s as easy as it looks—the zu just slots in before the verb:

- Hast du Lust darauf, ins Kino zu gehen? (Do you fancy going to the cinema?)

It gets a tiny bit trickier with those pesky separable verbs. Here, the zu slots in between the separable prefix and the verb stem. Check out this example with the verb anrufen, where the an is the separable prefix:

- Ich habe versucht, dich anzurufen. (I tried to call you.)

Sometimes you need a comma to set the clause off. If there’s more to the clause than just zu and your infinitive, you need a comma. Otherwise it’s optional. This is really just to help clarify the sentence and show proper word order.

Dartmouth’s German Studies Department has a lot of good examples to show you when you need to set the clause off by a comma, and when you don’t.

4. When Not to Use Zu

With Modal Verbs

German modal verbs include könnnen (to be able to), müssen (to have to), wollen (to want to), mögen (to like to), etc.

You might think that when we use modals in German sentences, we would need zu. However, modals never require the word zu in German.

Take the English sentence, “I want to sing.” Our German modal would be wollen. But if we said, “Ich will zu singen,” we’d be wrong.

Rather than meaning, “I want to sing,” this is grammatically incorrect, because modals already have the “to” built in. The correct way to say this would be, “Ich will singen.”

I know, I know—this is a little confusing, especially in comparison to the infinitive clauses with zu discussed above. Here’s a handy online worksheet where you can compare these two contexts further and practice applying zu the right way.

With Indirect Objects

Similarly, you don’t always need zu when referring to indirect objects, because the dative case can do the work for you!

Let’s say you wanted to translate the sentence “We give him a cake.”

In German, you can just say, “Wir geben ihm einen Kuchen.”

The sentence above reflects proper German word order, as indirect objects come before direct objects. By using the dative pronoun “ihm” , you are indicating he is receiving the direct object, der Kuchen. No zu is needed.

You can read up more about the wonders of the dative case in our article here!

Practice your zu usage and soon you’ll know the difference between all its uses—and be that much closer to fluency!

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing...

Want to know the key to learning German effectively?

It's using the right content and tools, like FluentU has to offer! Browse hundreds of videos, take endless quizzes and master the German language faster than you've ever imagine!

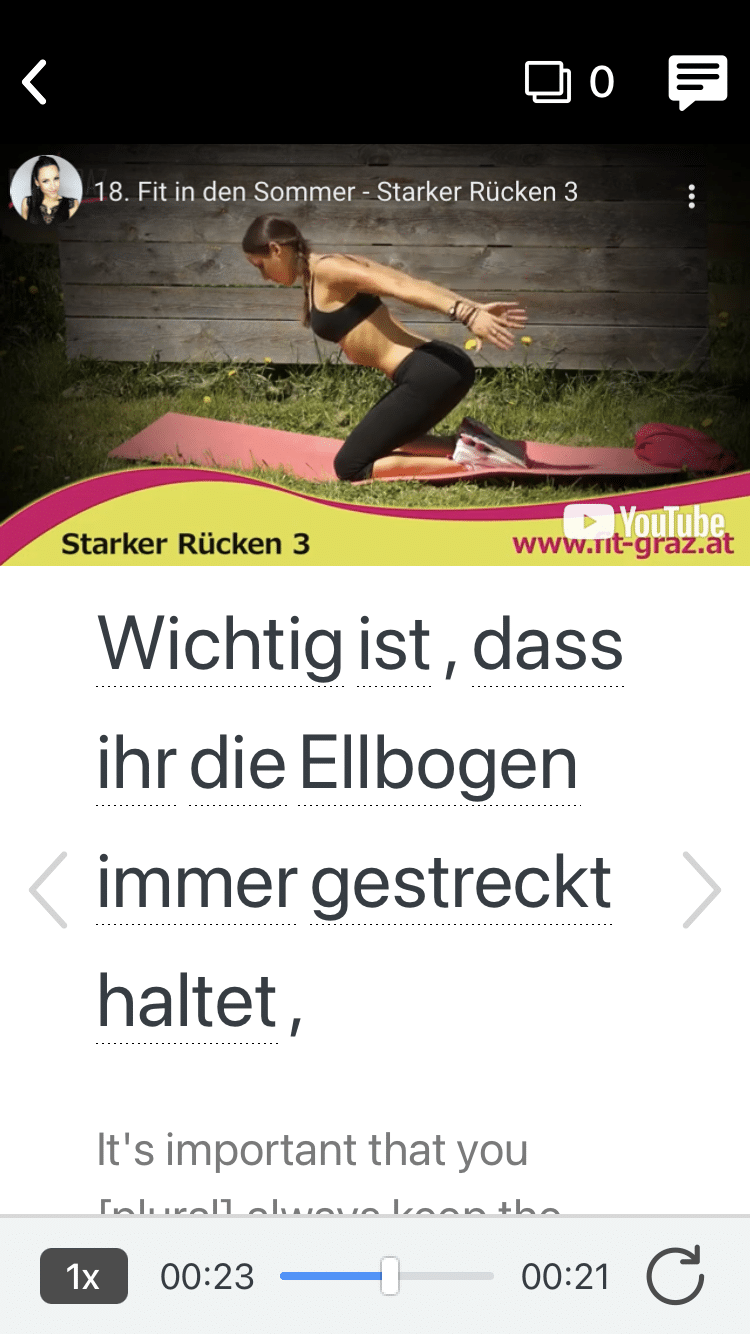

Watching a fun video, but having trouble understanding it? FluentU brings native videos within reach with interactive subtitles.

You can tap on any word to look it up instantly. Every definition has examples that have been written to help you understand how the word is used. If you see an interesting word you don't know, you can add it to a vocabulary list.

And FluentU isn't just for watching videos. It's a complete platform for learning. It's designed to effectively teach you all the vocabulary from any video. Swipe left or right to see more examples of the word you're on.

The best part is that FluentU keeps track of the vocabulary that you're learning, and gives you extra practice with difficult words. It'll even remind you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)