German Irregular Verbs: 5 Tips to Conjugate Them

If you’ve been studying German for a while, it should come as no surprise that the language has some wacky irregular verb forms.

And chances are that you’ve been getting some of them wrong.

“Great,” you’re probably thinking. “There are already more than enough ways to embarrass myself in German.”

But don’t worry! Just study our list below of five ways to get those irregular verbs right, and you’ll be talking flawlessly about eating in the past in no time.

Contents

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

What Are German Irregular Verbs?

To understand what German irregular verbs are, you need to understand their opposite: regular or “weak” verbs. These verbs follow a simple conjugation pattern.

Let’s use sagen (to say) as an example. Here’s how you’d conjugate it:

- Ich sage (I say)

- Du sagst (You say)

- Er/sie/est sagt (He/she/it says)

- Wir sagen (We say)

- Ihr sagt (You all say)

- Sie sagen (They say)

- Partizip II (Past Participle): Ich habe gesagt (I said)

- Präteritum (Simple Past Tense): Ich sagte (I said)

Simple, right? Just take the stem sag- and change the succeeding letters (or preceding letters, as in the case of the Partizip II) according to the pronoun or tense you’re using.

Now, imagine you really want to tell some friends a story in German. Let’s say this story is about a character who had ordered some food and was eating it.

You know that essen means “to eat” and you need the Präteritum to describe that action.

So…sie esste? Is that right?

If only. It’s actually, completely illogically, sie aß (she ate).

Essen is an example of an irregular German verb (also known as a “strong” verb). It’s “irregular” because it doesn’t follow the simple and straightforward conjugation rules that regular verbs do.

Remember our “to eat” example? In English, the past tense of “eat” is “ate” rather than “eated.” So “eat” is also an irregular verb in English!

That’s the good news: the concept of German irregular verbs isn’t that much different from its English counterpart. The bad news is that the conjugation rules for irregular verbs in German can be just as confusing as the English ones (for non-natives, anyway).

So how do you conjugate irregular German verbs? Without further ado, let’s dive right into the tips.

5 Ways to Get German Irregular Verbs Right

1. Learn the conjugations for the present tense.

Remember how, when conjugating verbs like sagen, the stem (sag-) remained the same in all the tenses? Unfortunately, the stem of many irregular verbs changes based on the conjugation, as well as in the two past tenses.

Some of these stem changes in the present tense simply involve adding an ä or ö in place of an a or o. Other stems in the present tense undergo a complete change.

A good way to tackle these verbs is to remember that they don’t all follow different rules. The verbs with vowel changes often follow similar patterns, for example, and the more you study German, the more you’ll develop a sense for how these verbs actually change.

Check out this helpful list for a study guide.

Let’s take a look at fahren (a verb with a vowel change) and geben (a verb with a complete stem change).

| Pronoun | fahren to go | geben to give |

|---|---|---|

| Ich I | Ich fahre I go | Ich gebe I give |

| Du You | Du fährst You go | Du gibst You give |

| Er He | Er fährt He goes | Er gibt He gives |

| Wir We | Wir fahren We go | Wir geben We give |

| Ihr You (all) | Ihr fahrt You (all) go | Ihr gebt You (all) give |

| Sie They | Sie fahren They go | Sie geben They give |

2. Learn the conjugations for the past tense.

All right, so you studied the pattern-following irregular verbs and memorized the really wacky ones. Present tense is no problem for you.

Then you realize you still want to tell that story about that character who ate something. You learned the irregular stem for essen (to eat): isst . Is the past form isste? No! The past tense of essen is aß , remember? How are you supposed to learn all of these forms?

Unfortunately, verbs like essen break the rules for Particip II and Präteritum as well.

But you’ll be glad to know there are still some patterns you can remember! The past participles of irregular verbs almost always end on -en rather than -t: essen (to eat) becomes gegessen, fahren (to travel) becomes gefahren. Many irregular verbs also have a vowel change in the past participle too: singen (to sing) becomes gesungen and trinken (to drink) becomes getrunken.

It helps to start by learning the most common ones that’ll serve you in many situations like bleiben (to stay), essen (to eat), fahren (to travel), gehen (to go), lesen (to read), schreiben (to write), sehen (to see) and trinken (to drink). You’ll soon start to get an innate sense of when to expect a vowel change, so they won’t shock you so much when you come across them!

Something I found helpful when memorizing unpredictable past tense stems is a little song. My German teacher played this tune for my class, and its gentle but persistent chant helped me slowly but surely stick these forms into my mind. You can find the lyrics here and follow along.

In general, listening can really help in hammering home verb forms, whether it’s listening to music or really any kind of audio material

Let’s look at common verbs like essen (to eat), lesen (to read) and rufen (to call).

| Verb | Particip II | Präteritum |

|---|---|---|

| essen to eat | Ich habe gegessen I ate | Ich aß I ate |

| lesen to read | Ich habe gelesen I read | Ich las I read |

| rufen to call | Ich habe gerufen I called | Ich rief I called |

3. Understand what a mixed verb is.

All right, so there are regular and irregular verbs.

Some verbs fall into an in-between category. If you’ve been saying Ich habe gedenkt instead of Ich habe gedacht (I was thinking), you’ve stumbled across the mixed verb problem.

Almost all mixed verbs are regular in the present tense, but in the past tense, they combine the ending –t for Particip II, and –te for Präteritum with the vowel change of an irregular verb.

The good news? There aren’t too many mixed form verbs. Look at the examples below to find out about the most common.

| Verb | Präteritum | Particip II |

|---|---|---|

| haben to have | hatte had | gehabt had |

| kennen to know | kannte known | gekannt knew |

| wissen to know | wusste known | gewusst knew |

| denken to think | dachte thought | gedacht thought |

| bringen to bring | brachte brought | gebracht brought |

| rennen to run | rannte ran | gerannt* ran |

| nennen to call | nannte called | gennant called |

| brennen to burn | brannte burned | gebrannt burnt |

4. Know how –ieren verbs work.

An –ieren verb is, as its name suggests, one of a handful of verbs (many of which came to German through French) that end in –ieren. They follow the pattern of regular verbs, except in one way.

In the Particip II form, instead of putting ge- at the beginning, you simply put a –t on the end.

| Verb | Particip II |

|---|---|

| Diskutieren to discuss | Ich habe diskutiert I discussed |

| Existieren to exist | Ich habe existiert I existed |

| Fotografieren to take pictures | Ich habe fotografiert I took pictures |

You also need to watch out for verbs with non-separable prefixes like beginnen, vergessen or verlieren. These verbs just take the irregular past participle ending of -en as well as any vowel changes, but don’t need a -ge at the beginning: beginnen – begonnen, vergessen – vergessen, verlieren – verloren.

5. Learn how to conjugate modal and auxiliary verbs.

Here’s the thing about modal and auxiliary verbs—they’re all irregular.

Unfortunately, they also show up frequently in German.

For example, the modal verbs include:

- können (can)

- müssen (must)

- wollen (want to)

- sollen (should)

- dürfen (to be allowed to)

- mögen (to like to)

As you can imagine, modal verbs are used in a wide variety of contexts. For example:

- Ich kann singen. (I can sing.)

- Wir dürfen ins Kino gehen. (We are allowed to go to the movies.)

- Sie darf nicht in der Disco tanzen. (She is not allowed to dance in the club.)

- Ich bin müde. (I am tired.)

- Sie müssen einen Computer finden. (They must find a computer.)

Meanwhile, the following auxiliary verbs are all used as helping verbs, which means you’ll need them a lot:

You use haben and sein to form the Particip II, which is the past tense most commonly used in spoken language. You use werden to form the passive tense, as well as for a panoply of other purposes. And, of course, these three common verbs are all irregular.

Luckily, you can read all about conjugating German modal and auxiliary verbs here.

German irregular verbs are a wild excursion into uncertainty and vowel changes, that’s for sure!

But once you’ve figured out how to conjugate all types of German verbs correctly, you’ll be well on your way to never making a conjugation mistake again.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing...

Want to know the key to learning German effectively?

It's using the right content and tools, like FluentU has to offer! Browse hundreds of videos, take endless quizzes and master the German language faster than you've ever imagine!

Watching a fun video, but having trouble understanding it? FluentU brings native videos within reach with interactive subtitles.

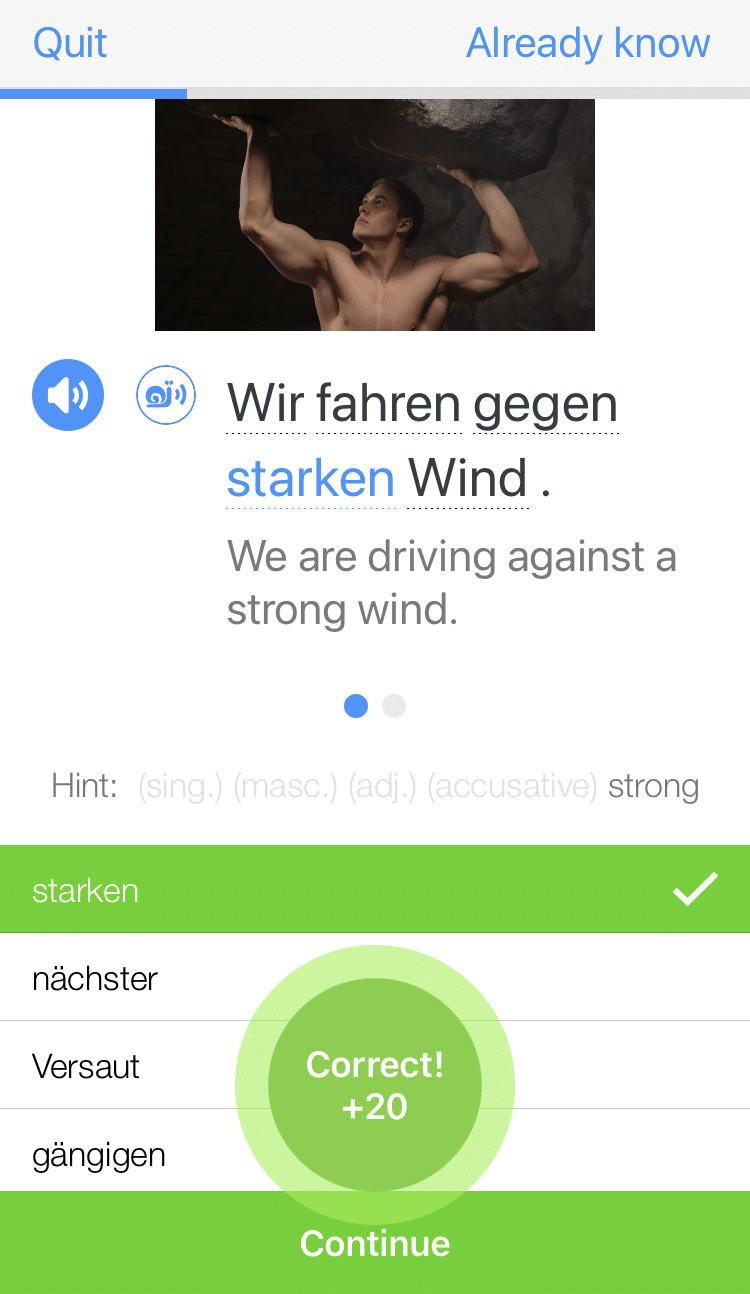

You can tap on any word to look it up instantly. Every definition has examples that have been written to help you understand how the word is used. If you see an interesting word you don't know, you can add it to a vocabulary list.

And FluentU isn't just for watching videos. It's a complete platform for learning. It's designed to effectively teach you all the vocabulary from any video. Swipe left or right to see more examples of the word you're on.

The best part is that FluentU keeps track of the vocabulary that you're learning, and gives you extra practice with difficult words. It'll even remind you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)