How to Determine French Gender for Masculine and Feminine Nouns

Masculin ou féminin ? (Masculine or feminine?)

Oh, the woes this question has brought me, you and every other French learner out there.

While there are no strict rules to memorize and follow, there are some general trends that will help you avoid getting stuck on this question.

In this post, I’ll show you everything you need to know to master French gender for nouns so you can speak more confidently—and correctly!

Contents

- What Is French Gender?

- How to Determine French Gender

- Quiz on Gender of French Nouns

- How to Master French Gender

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

What Is French Gender?

In French, nouns have grammatical gender, which means they’re classified as masculine or feminine. For example:

Masculine nouns: le livre (the book), le chat (the cat)

Feminine nouns: la table (the table), la voiture (the car)

When you learn a French word, you’ll typically see it paired with either its definite or indefinite article:

| Indefinite articles or "a/an" in English | Definite articles or "the" in English | Partitive articles or "some" in English: | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Masculine | un | le | du |

| Feminine | une | la | de la |

| Plural | des | les | des |

Gender Agreement

French adjectives and articles must agree with the gender of the noun they modify. If you’re describing a feminine noun with an adjective, both the adjective and the article must be in the feminine form. For example:

Masculine: un beau lac (a beautiful lake)

Feminine: une belle fleur (a beautiful flower)

In some cases, the verb must also agree with the gender of the subject (when it’s a noun) or direct object.

Gender agreement is an essential aspect of French grammar needed to construct grammatically correct sentences. To keep genders straight, I recommend that you try to always learn new words with their genders.

How to Determine French Gender

Most French teachers and fellow French speakers will tell you there’s no rhyme or reason to whether a noun is masculine or feminine. While there’s some truth to this, there are some general trends to get most nouns on lock.

Be aware that there are some tricky counterintuitive noun genders, for example, le féminisme (feminism) is masculine and la masculinité (masculinity) is feminine.

Typical Endings of Masculine Nouns

Looking at the ending of a noun may be the most effective way to determine its gender when you’re stumped.

Here’s a list of common endings for masculine nouns, but keep in mind that these “rules” don’t apply 100% of the time (as you’ll see from the exceptions).

| Noun Ending | Examples | Exceptions |

|---|---|---|

| -ant, -ent | le restaurant (restaurant), le président (president) | la dent (tooth), la jument (mare) |

| -eur | le professeur (teacher), le danseur (dancer) | la fleur (flower), la couleur (color) |

| -ien | le musicien (musician), le chien (dog) | |

| -oir | le devoir (duty), le miroir (mirror) | |

| -on | le ballon (balloon), le bouton (button) | la nation (nation), la boisson (drink) |

| -ot | le robot (robot), le chat (cat) | |

| Consonant + s | le fils (son), le laps (lapse) |

Typical Endings of Feminine Nouns

Here are some common endings for feminine nouns in French. Again, you can’t rely on them all the time, but I still find them useful for determining the gender of many French nouns.

| Noun Ending | Examples | Exceptions |

|---|---|---|

| -ance, -ence | la chance (luck), la présence (presence) | le silence (silence) |

| -e | la table (table), la robe (dress) | le livre (book), le lobe (earlobe) |

| -ie, -ue | la vie (life), la rue (street) | le génie (genius), l'incendie (fire) |

| -ion | la nation (nation), la décision (decision) | le million (million), le bastion (stronghold) |

| -té | la beauté (beauty), la vérité (truth) | le comté (county), le côté (side) |

Masculine and Feminine Noun Categories

Certain categories of nouns tend to be masculine or feminine. The gender of the noun category will usually match the gender of the nouns in that category as well.

For example, since un mois (a month) is masculine, names of specific months, such as décembre (December), are masculine as well.

Here are some more common examples of masculine noun categories:

| Noun Category | Examples | Exceptions |

|---|---|---|

| Languages | le français (French), l'espagnol (Spanish) | une langue (a language) is feminine |

| Seasons | le printemps (spring), l'hiver (winter) | une saison (a season) is feminine |

| Planes | un avion (a plane), le Concorde (Concorde) | |

| Cheeses | le fromage (cheese), le Roquefort (Roquefort) |

Here are some examples of feminine noun categories:

| Noun Category | Examples | Exceptions |

|---|---|---|

| Fruits | une banane (a banana), une pomme (an apple) | un fruit (a fruit) is masculine |

| Scientific fields | la science (science), la physique (physics) | |

| Seas | la mer (the sea), la Méditerranée (the Mediterranean) |

Places

Continents and planets in French are feminine. For example, l’Asie (Asia) and la Terre (Earth).

Countries that end in -e are generally feminine. For example, la France (France) and la Suisse (Switzerland).

Countries that end in a different vowel or a consonant are generally masculine. For example, le Canada (Canada) and le Japon (Japan).

This is a pretty standard rule with only a handful of exceptions, noted below:

le Mexique (Mexico)

le Bélize (Belize)

le Cambodge (Cambodia)

le Mozambique (Mozambique)

le Zaïre (Zaire)

le Zimbabwe (Zimbabwe)

Derivative Nouns

Nouns derived from a verb — referring to something or someone carrying out that verb’s action — typically use the ending -eur, and will be masculine. For example:

l’aspirateur (the vacuum)

l’ordinateur (the computer)

Nouns that are derived from adjectives and end with –eur are feminine. For example:

la rougeur (the redness)

la largeur (the width)

la pâleur (the paleness)

Nouns That Have Masculine and Feminine Forms

Animals

When talking about certain animals in French, you refer to the male version of the species with a masculine noun and the female of the species with a feminine noun. For example:

un étalon (a stallion) / un cerf (a stag)

un lion (a male lion) / une lionne (a female lion/lioness)

Although, some nouns for animals refer to both genders. For example:

une souris (a mouse)

un cheval (a horse)

Job Titles

Most job titles have both a masculine and feminine form. Here are some examples:

| English Job Title | Masculine Form | Feminine Form |

|---|---|---|

| an actor | un acteur | une actrice |

| a baker | un boulanger | une boulangère |

| a nurse | un infirmier | une infirmière |

| a cashier | un caissier | une caissière |

| a lawyer | un avocat | une avocate |

| a pharmacist | un pharmacien | une pharmacienne |

| a student | un étudiant | une étudiante |

| a waiter | un serveur | une serveuse |

| an engineer | un ingénieur | une ingénieure |

| a painter | un peintre | une peintre |

Un professeur (a teacher) and un écrivain (a writer) are usually only employed in the masculine.

While une chef (a chef) is commonly accepted in Switzerland and Francophone Quebec, only un chef is generally used in France.

Quiz on Gender of French Nouns

Now that we’ve gone over all the basics about the gender of French nouns and the patterns they follow, it’s time to test what you’ve learned!

Take the quiz below (without looking at the answers above!) and just refresh the page if you want to start over or retake it.

How to Master French Gender

As you dive into the words and patterns above, you’ll want to have some go-to tools to apply what you’re learning. Here are some helpful places I recommend for practicing French noun gender:

- There are many useful quizzes you can use to practice French gender, like this Sporcle endings quiz, this 10-question quiz from Talk in French or these “Trial by Fire” exercises from LanguageGuide.org.

- Use Vocabulary Stickers to label things in your house with their French name. These durable (but easy-to-remove) stickers are color-coded for gender, adding a visual element for even easier memorization.

- Consume French content like films, books, comic books, and magazines that can help you learn vocabulary (with gender) and help increase your overall fluency.

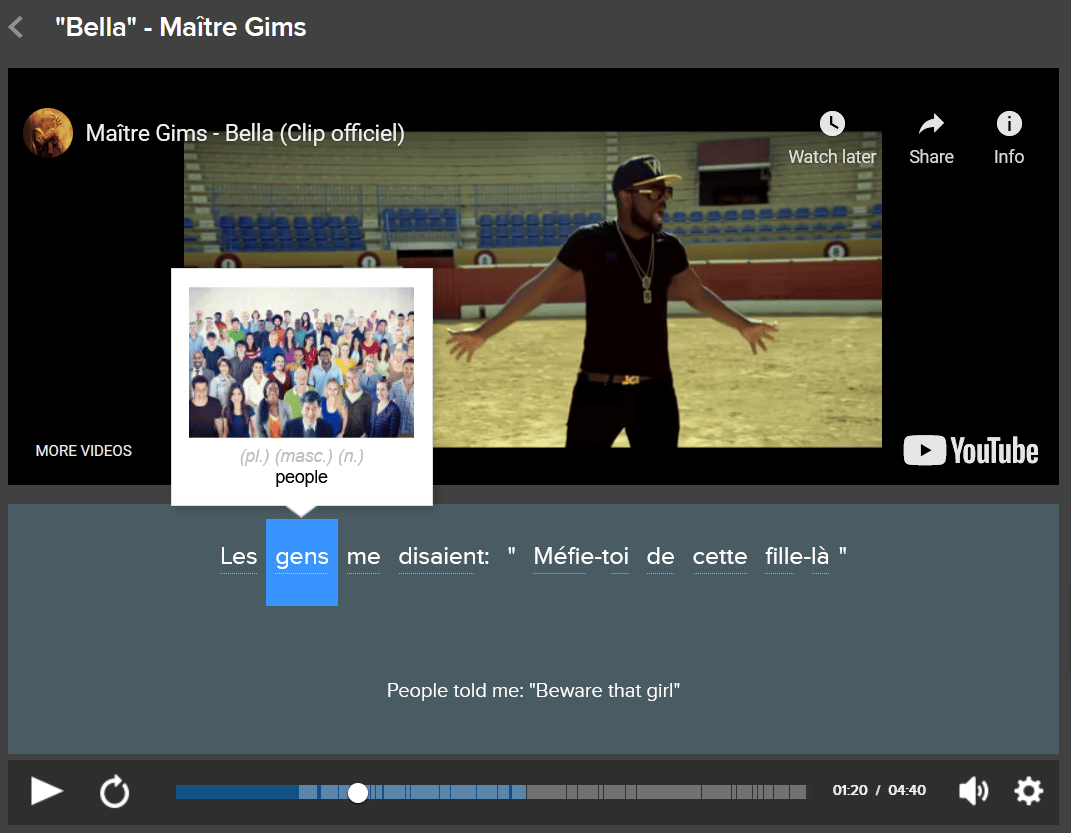

- Use an immersive language learning program like FluentU to see gender rules being applied in native French speech. FluentU has many authentic French videos like movie and TV show clips, news segments, vlogs and more—all with interactive subtitles.

Just hover over or click on any word to see its meaning, gender, example sentences and more. Save words you struggle with into a flashcard deck and practice them with personalized quizzes on the website or by downloading the iOS or Android app.

Games to Reinforce French Gender

Since French gender can be a bit of a dull topic, add some fun to your study time by playing games that will help you memorize the gender of common nouns.

- The Flashcard Race: Make or print about 50 flashcards with a French word on one side and the gender on the other. Then start the clock! Look at the word and say it aloud with the indefinite article. For every wrong answer, add 5 seconds to the clock. Your job is to defeat your earlier time!

- The Memory Game: Make 2 sets of matching cards, one set of French words and another of genders. Then find the matches by flipping each card and finding the appropriate matching indefinite article. When you’re done, check your work against a master list. You get points for every correct match. You can also make your own Memory Match game.

- Red Light Green Light: An arbitrator with a dictionary or app stands at the front of the room or yard. They call out a word with the gender—but they can choose whether they use the correct gender or not. If the gender is correct, you may step forward. If it’s incorrect, you may not. Those who run forward when the gender is incorrect must go back to the starting line. This game is even more fun if you blindfold the participants!

- Race! Irregular Feminine Forms: One person chooses a list of 20 masculine words with a feminine form (ideally irregular). When the timer begins, the other person comes up with as many feminine forms as possible in 1 minute. All correct answers get 1 point. All unanswered words get 0 points. All incorrect answers lose 1 point. Total up, and then it’s the other person’s turn to race. This game can also be played alone.

- Categories (with Gender Rules!): In the traditional Categories game, you’d give a category, for example, animals, and everyone would go around the circle listing words until someone either can’t think of one or repeats one that’s already been said. Gender rules can modify the game in several ways.

One version is simply to say that each word must be accompanied by an indefinite article. Another version is to say that the category is animals in the feminine. The last, most difficult version is to alternate between masculine and feminine words. For example: un zèbre (a zebra), une fourmi (an ant), un lion (a lion), une chienne (a female dog).

As you delve into the fun world of the past tense, pronouns and compound tenses, you’ll find the gender of your nouns becoming more and more important.

There may seem to be no sense to it—and often there isn’t—but it’s something we French speakers must try to conquer, both beginners and fluent speakers alike!

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)