How to Practice Chinese Tones: 11 Foolproof Tips to Mastering Pronunciation

Tones are one of the biggest challenges beginners face when they start learning Chinese.

But the good news is, you definitely don’t need to visit or be in China to get this linguistic feature down pat.

In this post, I’ll show you exactly how to practice Chinese tones using 11 methods, plus why they’re so important.

And by the end, you’ll certainly be on your way to hearing a surprised, “你的汉语很好!” (nǐ de hàn yǔ hěn hǎo — your Chinese is very good!).

Contents

- What Are the Chinese Tones?

- 11 Tips to Practice Mandarin Chinese Tones

-

- 1. Learn to hear tones

- 2. Think about how your native language uses pitch

- 3. Listen for aspects of tone besides pitch

- 4. Practice hearing tones on one syllable, then in combination

- 5. Test yourself

- 6. Use online resources for practicing tones

- 7. Practice pronouncing tones

- 8. Work with a native speaker

- 9. Record yourself

- 10. Practice until the tones start to come naturally

- 11. Memorize tones

- Why Do I Need to Learn Chinese Tones, Anyway?

- And One More Thing...

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

What Are the Chinese Tones?

Mandarin Chinese is a tonal language, which means the tone you use when pronouncing a word changes its meaning.

There are five tones in Mandarin Chinese, and they’re represented by tone marks placed above the vowel that is being stressed or pitched a certain way.

The five tones are:

- First tone (Flat)

- Second tone (Rising)

- Third tone (Falling-Rising)

- Fourth tone (Falling)

- Fifth tone (Neutral)

Here’s an example of tone marks, sounds and how the tones alter a word’s meaning:

To an untrained ear, these words can be hard to differentiate.

But luckily, there are several ways you can fine-tune your listening skills and learn to recognize tones easily.

11 Tips to Practice Mandarin Chinese Tones

1. Learn to hear tones

When you were a baby, you could hear the difference between mā ma (mother) and mà mā (swear at one’s mother).

Or at least you could have, if you had been listening to some extraordinarily impolite person speak Mandarin.

But your brain has long since determined that this isn’t important information. Now, many years later, you need to retrain your brain to think of pitch as an important feature again.

But how?

Many people characterize Chinese as sounding “sing-songy.”

If you’re one of them, good news: You’re hearing tones!

The pitch moving up and down from word to word is what gives English speakers this impression. You can hear tones, so now you just have to figure out how to process them.

If you don’t recognize tones yet, I highly recommend practicing with Chinese videos or podcasts.

Even though you won’t understand everything, it’ll help get your ear used to hearing the tones and native speaker pronunciation.

Make sure they’re not speaking too fast though. You can use a resource like FluentU, which lets you learn Chinese with native-speaker videos even at the beginner stage.

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Or you can start listening to Chinese podcasts, like the ones mentioned here.

2. Think about how your native language uses pitch

You may not be a native speaker of a tone language, but all spoken languages use pitch to distinguish some sort of meaning.

If you’re a native English speaker, the pitch of your voice conveys things like whether you’re asking a question or making a statement.

It also shows how sure you are of what you’re saying, and how you feel about it.

Try this: Say “yes” like you’re absolutely sure you mean it. Now say “Yes?” as if you’re not so sure.

Can you hear the difference?

Now try doing the same thing, but instead of an English word, say it with a syllable like ma.

Now, click the words to hear how mà and má are pronounced:

骂 (mà)

麻 (má)

Do you hear a resemblance to what you just said?

Listen again to the Chinese tones and think about what they sound like to you.

3. Listen for aspects of tone besides pitch

If you’re having a tough time hearing tones, listen for things besides pitch.

Do you hear creaky voice?

(That “I just got out of bed and can’t quite get my voice working correctly yet” croaking sort of sound).

Not all speakers have creaky third tones, but they’re pretty common.

Or try length. Was the syllable long and drawn out? Chances are good that was a third tone.

Really short? Probably a fourth tone at work.

These length differences start to disappear in real speech, but they’re real enough in the “reading a vocabulary list” type of speech you’re likely to hear in a dictation test. Let them work for you.

Or pretend you’re listening for stress.

That neutral tone? Think of it as an unstressed syllable and see whether you can hear it better.

4. Practice hearing tones on one syllable, then in combination

The first step to practicing your tone listening skills is, of course, to try to hear the four basic tones by themselves.

There are numerous recordings available that will let you do this.

Aside from tone tests in class and the odd one-syllable vocabulary word, you won’t often encounter solitary tones.

So I recommend that, as soon as possible, you move on to working on hearing tones in longer combinations—at least two syllables long.

Tones sound different in context than they do in isolation. The most dramatic example of this is third tone.

Chinese textbooks universally teach you that the third tone is falling-rising.

But—and this is really, really important—it’s only like that when you say it all by itself, or maybe at the end of a sentence.

In normal speech, the third tone is more often just a low tone.

If you spend too much time training yourself on one-syllable words, you may have a hard time hearing the difference between second and third tone in context.

(I just might be speaking from experience on this one).

The best resources for this kind of listening practice—aside from a real, and very patient Chinese speaker, of course—are recordings of real people speaking words or sentences.

You’re not trying to learn to speak to a computer, so don’t learn to listen from a synthesized voice.

Even tone-learning apps recorded by real people won’t help you learn what real speech sounds like if they rely on spliced-together syllables.

5. Test yourself

Use listening materials that force you to make a choice.

Which tone was it that you just heard?

This type of choosing, followed immediately by feedback, helps with learning.

Once you know where you consistently make mistakes, practice listening to those tones and then test yourself again.

Eventually, I promise, your brain will begin to sort it out, and you’ll start hearing differences.

6. Use online resources for practicing tones

Unfortunately, I haven’t come across the absolutely perfect online resource specifically made for learning tones.

However, here are a few that at least meet the minimal requirement of having real people and real speech.

Sinosplice has a really useful set of recordings for the four tones in isolation, and then the four tones (plus neutral tone) in every possible combination.

Use it when you want to listen to specific tones or pairs of tones.

Pinyin Practice lets you quiz yourself on one or two-tone combinations and keeps track of how many you have right and wrong.

This is the best resource I’ve found for testing yourself as I mentioned earlier.

Finally, Arch Chinese also lets you quiz yourself on the four tones in isolation.

I mention it here just because this gives you another person to listen to, and because they also have a pinyin chart with audio that you can use for practice when you just want to choose the pairs of sounds.

7. Practice pronouncing tones

So you can hear the difference between all four Mandarin tones now, right?

At least sort of, sometimes?

The next trick is to figure out how to say them yourself.

If you can already hear the tones, you should know what you’re aiming for.

- Listen and repeat. Listening and repeating is a tried and true form of learning to say words in a new language. So don’t underestimate its effectiveness. Practice repeating after native speakers as often as you can.

- Speak slowly at first. When you’re first learning Chinese, you’re training yourself to make all sorts of new sounds. When you’re practicing on your own, slow things down so you can fit everything in. Once your mouth gets the hang of it, it won’t seem so impossible.

- Exaggerate. Use the full range of your voice. Pretend you’re a voice actor telling a story. Sing if you have to! Get your highs up high and your lows down low. You don’t want to sound like this forever, of course, but it may help you get going in the beginning. Oh, but that neutral tone? Don’t exaggerate it at all. In fact, think anti-exaggeration. Aim for short and quick and in the middle, and you’ll probably get it right.

8. Work with a native speaker

If at all possible, find yourself a native Mandarin speaker who’s willing to give you honest feedback on your pronunciation.

Ideally, find someone who can explain what it is that you’re doing wrong—someone who can tell you that your low tone wasn’t low enough or that your rising tone didn’t really rise far enough.

If you’re having a tough time knowing what to do, or you feel like you get everything wrong, try starting with some simple mimicking—he or she says a word, and you copy it.

Sometimes, even though you think you can’t hear what people are doing, you can still mimic them correctly.

And once you’ve got that down, you can work from there to build the correct habits.

You can find native speakers on language exchange apps like HelloTalk and Tandem, or online tutoring platforms like italki.

(You can also check out our full, in-depth reviews of HelloTalk here and italki here.)

9. Record yourself

If you can’t find someone to work with, find recordings of a native Mandarin speaker instead.

Then record yourself saying the same things and compare. (And put your hard work hearing tones to good use!)

If you’ve put in your time with your listening practice, you should be able to get some feel for whether or not you’re on the right track.

Some useful beginning tone practice that you could use for this can be found on FluentU, like this one.

10. Practice until the tones start to come naturally

When do you decide you’ve spent enough time on tones?

If you can put a sentence together without thinking the whole time about pronunciation—and get your pronunciation correct—you’re well on your way.

If you say a word with the wrong tone and realize it sounds wrong, you’re in good shape.

Eventually, these things do start to come more naturally.

11. Memorize tones

This final tip isn’t as obvious as it seems: Make sure that you memorize the correct tones for all the words you learn.

If you use flashcards, don’t take a “close enough” approach—if the tone is wrong, you’re wrong, and you need to review it again.

Some people find it useful to color coordinate their flashcards according to the tone, and many programs for studying Chinese have this functionality built in.

If you’re more of a kinetic learner than a visual learner, maybe you’d find it helpful to use hand motions for the tones.

Or if you’ve nailed the pronunciation, try saying the correct answer out loud instead of reviewing silently. Saying and hearing the correct pronunciation will help to reinforce it.

If you find all of this memorizing business frustrating, remember, the more time you put into learning tones early on in your Chinese learning efforts, the less time you’ll have to spend unlearning bad habits later on.

Your hard work will pay off in the end—and even before then, you just may find your pronunciation to be the envy of your classmates.

Why Do I Need to Learn Chinese Tones, Anyway?

- Over half of the world’s languages use tone to distinguish words. This is a principle that will take you far in learning a new language and culture: Strange is going to become your new normal.

- If you ignore tones, you will be mispronouncing every single word. You might think you’re politely complimenting your mother-in-law on the food she ordered while in fact, you’re swearing at her! Not a mistake you want to make.

- Chinese people won’t understand you if your tones are wrong (without context). While my friend may do just fine with her ten toneless Chinese phrases that she uses during her two-week trip to China (and I’ve heard foreigners carry on entire conversations in toneless Chinese), there are some big spaces in between absolute beginner and fluent Chinese where correct pronunciation will be absolutely necessary.

- The best time to practice tones is when you start learning the language. And then keep practicing until you get it right. Although it may feel like something disjointed to you, tone isn’t a separate feature of the language. It’s much harder to fix deeply ingrained habits than it is to make the right habits from the beginning. You can put off memorizing characters, but you’ll regret putting off tones.

While tones are important, don’t let the fear of being misunderstood stop you from speaking.

Chinese speakers tend to be extremely forgiving of foreign accents.

This may be because there’s a large amount of diversity in the way Chinese people pronounce tones, so they’re used to hearing tones that differ from the standard Putonghua (Mandarin).

Most Chinese people I’ve met are happy just to hear a foreigner try to speak their language, so don’t wait until your pronunciation is perfect to start trying.

And there you have it—11 easy ways to train your English-hearing ear to identify and understand Chinese tones.

Consistently use these best practices and you’ll be on your way to better Chinese listening comprehension in no time.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing...

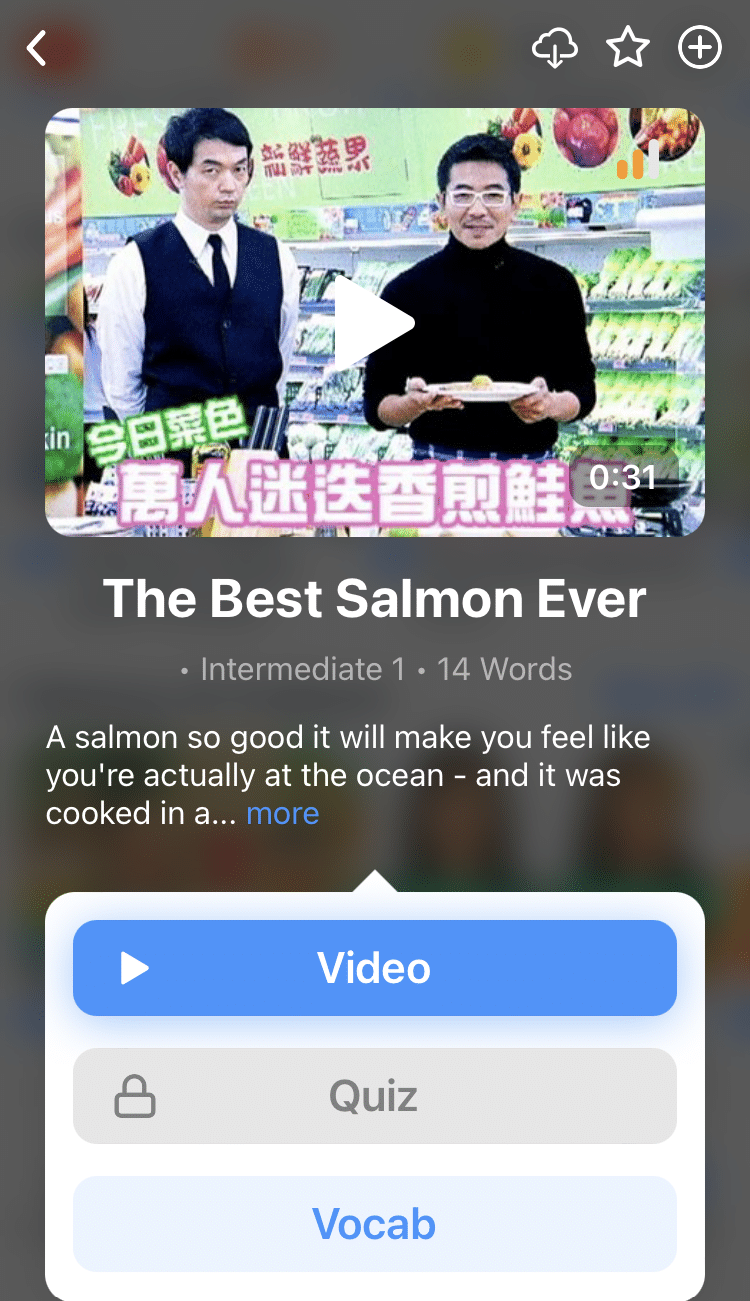

If you want to continue learning Chinese with interactive and authentic Chinese content, then you'll love FluentU.

FluentU naturally eases you into learning Chinese language. Native Chinese content comes within reach, and you'll learn Chinese as it's spoken in real life.

FluentU has a wide range of contemporary videos—like dramas, TV shows, commercials and music videos.

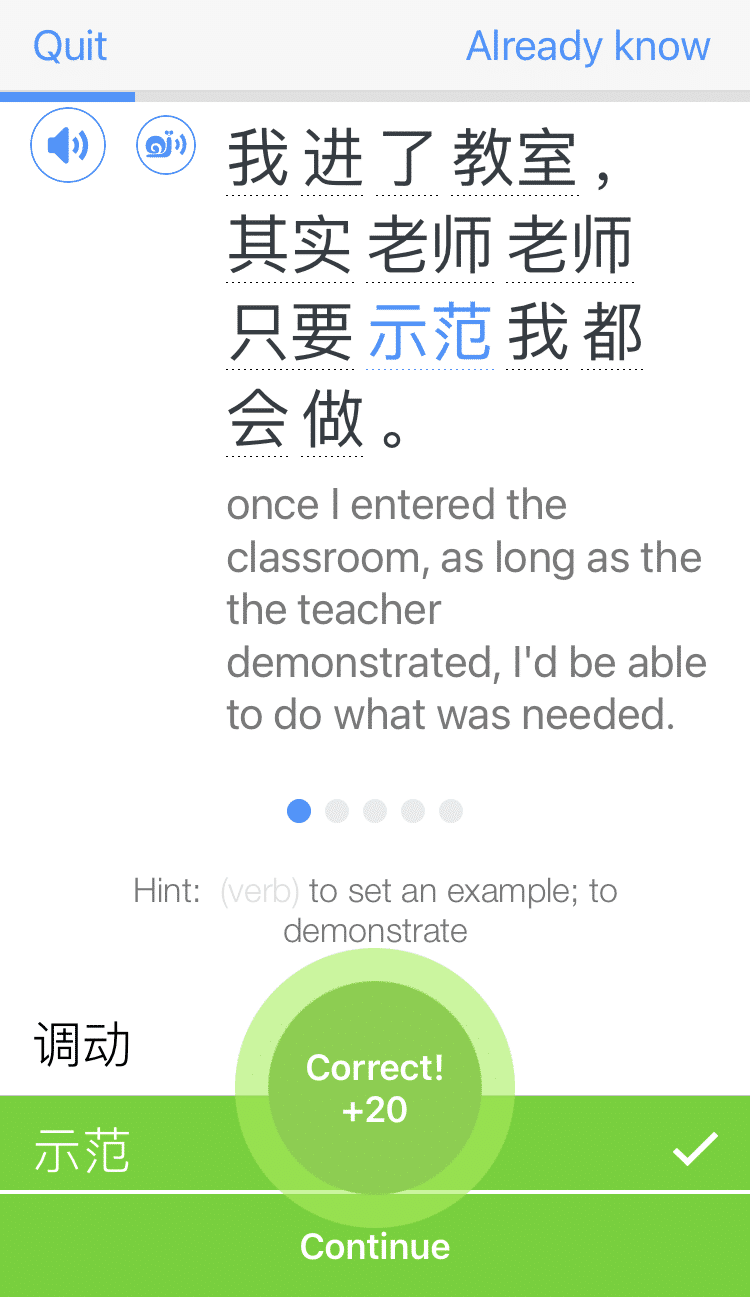

FluentU brings these native Chinese videos within reach via interactive captions. You can tap on any word to instantly look it up. All words have carefully written definitions and examples that will help you understand how a word is used. Tap to add words you'd like to review to a vocab list.

FluentU's Learn Mode turns every video into a language learning lesson. You can always swipe left or right to see more examples for the word you're learning.

The best part is that FluentU always keeps track of your vocabulary. It customizes quizzes to focus on areas that need attention and reminds you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. You have a 100% personalized experience.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)