How to Master Chinese Tones: A Comprehensive Guide

Chinese is a tonal language, which means that the tone or pitch you use when you say a word determines its meaning.

It might sound intimidating, but I promise it’s simpler than you’d expect. After all, we use tones in English all the time to indicate questions and emotions.

Let’s get familiar with the sounds of Mandarin Chinese tones and learn how to master them.

Contents

- What Are Chinese Tones?

- What Is Chinese Pitch Contour?

- Chinese Tone Changes

- Chinese Tone Pairs

- How to Practice Chinese Tones

- And One More Thing...

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

What Are Chinese Tones?

Every language has its own unique sound system. Linguists call the study of these systems phonology.

Mandarin Chinese has its own sound system too, and tones are an essential part of it.

In Chinese, the tone of a word is what gives it meaning. When you change the tone—or accidentally use the wrong one—you change the meaning of the word. Take, for example, these words:

妈 (mā) — mom

麻 (má) — hemp or flax

马 (mǎ) — horse

骂 (mà) — to scold or verbally abuse

吗 (ma) — a question particle

While each of these words looks as if they sound the same, they have different tones—which give them different meanings.

1. First tone (flat tone)

The first tone is made when your voice becomes higher and flatter. The pitch is raised and the syllable is pronounced with a drawn-out tone that doesn’t drop or rise.

In pinyin, the first tone is written as a long line above the vowel or as the number 1 (for example, instead of mā you might occasionally see ma1). The numerical version isn’t near as common as the actual tone mark, so you likely won’t see it as often.

喝 (hē) — to drink

天 (tiān) — sky

黑 (hēi) — black

一 (yī) — one

发 (fā) — to send

深 (shēn) — deep

瓜 (guā) — melon

猫 (māo) — cat

三 (sān) — three

出 (chū) — to go out

2. Second tone (rising tone)

The second tone is made with a rising voice. The pitch starts out low and then becomes higher. In pinyin, it’s written as a rising dash above the vowel or the number 2 (i.e. mang2):

忙 (máng) — busy

球 (qiú) — ball

龙 (lóng) — dragon

喉 (hóu) — throat

来 (lái) — to come

明 (míng) — bright

难 (nán) — difficult, hard

还 (hái) — to return

时 (shí) — time

房 (fáng) — house

3. Third tone (dip tone)

The third tone is one of the hardest for Mandarin learners. The pitch falls lower before rising higher again.

In pinyin, the third tone is written as a dip above the vowel or the number 3 (i.e. wo3):

我 (wǒ) — I/me

好 (hǎo) — good

你 (nǐ) — you

很 (hěn) — very

点 (diǎn) — point

姐 (jiě) — elder sister

也 (yě) — also

狗 (gǒu) — dog

小 (xiǎo) — small

可 (kě) — can

4. Fourth tone (falling tone)

To pronounce the fourth tone correctly, say the word with force, making your pitch fall. In pinyin, the fourth tone is written as a falling slant or dash above the vowel, or the number 4 (i.e. shi4):

是 (shì) — to be

后 (hòu) — behind

不 (bù) — no, not

热 (rè) — hot

日 (rì) — day

四 (sì) — four

爸 (bà) — dad, father

那 (nà) — that

下 (xià) — down

去 (qù) — to go

5. Fifth tone (neutral tone)

Whether the fifth tone is actually considered a tone is up for debate. Instead of making your voice go up or down, this tone is simply neutral—which means the word has no tone.

Pinyin doesn’t mark the fifth tone because there’s nothing you have to change or emphasize, although you’ll sometimes see it represented by the number 5 (i.e. ma5).

For example, the previously mentioned question particle 吗 turns statements into yes/no questions and is pronounced with a neutral (or no) tone.

Other neutral tone words include:

吧 (ba) — suggestion particle (turns a statement into a suggestion)

子 (zi) — child/son (usually comes at the end of words, like 孩子 (hái zi) — child)

儿 (er) — R sound

的 (de) — possessive particle

呢 (ne) — particle for asking questions back to the original asker

What Is Chinese Pitch Contour?

Knowing the five levels of contour is meant to help you determine which pitch to use when pronouncing each tone. But if it doesn’t help (or makes you more confused), you’re welcome to ignore it.

There are five pitch contour levels:

5 = High

4 = Mid-high

3 = Middle

2 = Mid-low

1 = Low

Let’s take a look at the pitch levels of each tone:

First Tone = Level 5 to Level 5 (or, “high pitch” to “high pitch”)

Second Tone = Level 3 to Level 5 (or, “middle pitch” to “high pitch”)

Third Tone = Level 2 to Level 1 to Level 4 (or, “mid-low pitch” to “low pitch” to “mid-high pitch”)

Fourth Tone = Level 5 to Level 1 (or, “high pitch” to “low pitch”)

Fifth Tone = no pitch

Chinese Tone Changes

You should be aware that Chinese tones can change when used in specific sequences.

In other words, certain tones become different tones when paired with others.

Third tone changes

Third tone + third tone = second tone + third tone.

If one word with a third tone is followed by another word with a third tone, the first one becomes a second tone.

For example:

我很忙 (wǒ hěn máng) — “I am busy” becomes 我很忙 (wó hěn máng)

Note that in pinyin, the tone change is not written. You simply must remember that you need to change the first word to a second tone.

The third tone can become neutral.

When followed by another tone, the third tone can become neutral or dropped.

This is optional, but many Chinese speakers do it, as it requires less effort and makes speech faster.

Even if you don’t use it, it’s important to be prepared for when a Chinese speaker does. For example, 考试 (kǎoshì) — “test” can become 考试 (kaoshì). Again, this tone change is not marked by pinyin.

一 (yī) tone changes

一 (yī) + fourth tone = 一 (yí) + fourth tone.

When the word 一 (yī) — “one” is followed by a fourth tone, it changes to a second tone.

You’ve probably seen this happen without even realizing it. Unlike most other tone changes, many textbooks and online courses mark this tone change for you.

For example:

一下 (yī xià) — “a bit” becomes 一下 (yí xià)

一定 (yī dìng) — “definitely” becomes 一定 (yí dìng)

一 (yī) + any tone = 一 (yì) + any tone.

Any time 一 (yī) is paired with another tone, it changes to a fourth tone: 一 (yì).

For example:

一般 (yī bān) — “usually” becomes 一般 (yì bān).

一起 (yī qǐ) — “together” becomes 一起 (yì qǐ).

一 (yī) can become a neutral tone.

Similar to the third tone, 一 (yī) can drop its tone when placed in between two words.

Dropping the tone is optional, but if you don’t, the same rules apply.

For example:

休息一下 (xiūxi yī xià) — “to rest a bit” becomes either:

休息一下 (xiūxi yí xià) with a second tone, or

休息一下 (xiūxi yi xià) with a neutral tone.

快一点 (kuài yī diǎn) becomes either:

快一点 (kuài yì diǎn), or

快一点 (kuài yi diǎn).

The number 一 (yī) stays the same.

When counting, the number 一 (yī) does not change its tone.

However, the number 一百二十六 (yī bǎi èr shí liù) — “126” becomes 一百二十六 (yì bǎi èr shí liù).

This is also true when counting items, such as 一个苹果 (yī gè píng guǒ) — “one apple,” which changes to 一个苹果 (yí gè píng guǒ).

不 (bù) tone changes

不 (bù) + fourth tone = 不 (bú) + fourth tone.

When the word 不 (bù) — “no/not” is followed by another fourth tone, it changes to a second tone. For example:

不是 (bù shì) — “to not be” becomes 不是 (bú shì).

It can be neutral when in between two words.

When placed between two words to make a phrase, 不 (bù) can become a neutral tone. Although this is optional, it’s important to be prepared for when native speakers do it.

For example:

吃不完 (chī bù wán) — “can’t finish eating” can become 吃不完 (chī bu wán)

差不多 (chà bù duō) — “more or less” can become 差不多 (chà bu duō).

去不去 (qù bù qù) — “will you go?” can become 去不去 (qù bu qù).

Chinese Tone Pairs

You’ll rarely find full-length sentences in Chinese that only use one tone.

In fact, many Chinese words consist of two tones. When this happens, you’ve come across a tone pair.

First tone pairs

First Tone + First Tone: 今天 (jīn tiān) — today

First Tone + Second Tone: 经常 (jīng cháng) — often

First Tone + Third Tone: 多少 (duō shǎo) — how many

First Tone + Fourth Tone: 帮助 (bāng zhù) — to help

Second tone pairs

Second Tone + First Tone: 明天 (míng tiān) — tomorrow

Second Tone + Second Tone: 同学 (tóng xué) — classmate

Second Tone + Third Tone: 还有 (hái yǒu) — and

Second Tone + Fourth Tone: 前面 (qián miàn) — in front

Third tone pairs

Third Tone + First Tone: 喜欢 (xǐ huān) — to like

Third Tone + Second Tone: 警察 (jǐng chá) — police

Third Tone + Third Tone: 哪里 (nǎ lǐ) — where

Third Tone + Fourth Tone: 礼貌 (lǐ mào) — polite

Fourth tone pairs

Fourth Tone + First Tone: 信息 (xìn xī) — news

Fourth Tone + Second Tone: 地图 (dì tú) — map

Fourth Tone + Third Tone: 入口 (rù kǒu) — entrance

Fourth Tone + Fourth Tone: 现在 (xiàn zài) — now

How to Practice Chinese Tones

The key to mastering tones in a short amount of time isn’t just repetition. It’s how you practice and what resources you practice with.

Use these methods to practice Chinese tones until they become second nature:

Write the tones out

Not only is listening to tones important but writing them out is too, as it makes remembering tone pairs a bit easier.

A great resource for learning how to use, write and understand tones and tone pairs is the Yoyo Chinese Pinyin Series on YouTube. This video breaks down everything you could need to know about Chinese tones as well as how to properly study them.

Every Chinese learner should also bookmark this Yoyo Chinese Pinyin Chart. This user-friendly, simple chart has every type of pinyin you’ll ever use in the Chinese language. Any level of learner could use this chart, but it’s especially valuable for beginners.

Say the tones with gestures

For those that are just starting out, this strategy will keep your tone pronunciation in check. All you have to do is mimic the movement of the tone with either your finger or your whole hand, kind of like a conductor of an orchestra.

These are the gestures you can use as you’re reading characters with different tones:

- First tone (—) — Draw a straight line above your head to keep your pitch high and level. Notice how characters in the first tone tend to sound longer than the others, so try to draw a longer line or draw the imaginary line slowly.

- Second tone (/) — Draw a diagonal quickly from the bottom left to the top right to slightly increase the pitch of your voice.

- Third tone (V) — Draw a “V” or a “U” as a guide to scoop or drop, and then raise your pitch.

- Fourth tone (\) — Draw a diagonal quickly from the top left to the bottom right to add a hard stress to the pinyin.

- Fifth/Neutral tone (.) — Draw a dot to keep the pronunciation short and succinct.

Practice repeating tone pairs out loud

A good resource to help practice your tone pairs is Sinosplice. Mandarin Chinese Tone Pair Drills is a type of Sinosplice software that takes a radical, unique approach to teaching students tonal Chinese.

You’ll need to have some foundational knowledge of tones before using this product, but it can certainly help you forge a more fluent bond with tones through regular use.

Listening Practice

Hearing and recognizing tones can be just as tricky (if not more) than pronouncing them yourself. Finding a good audio source, listening to it and trying to identify tones and tone pairs is a great way to improve listening comprehension.

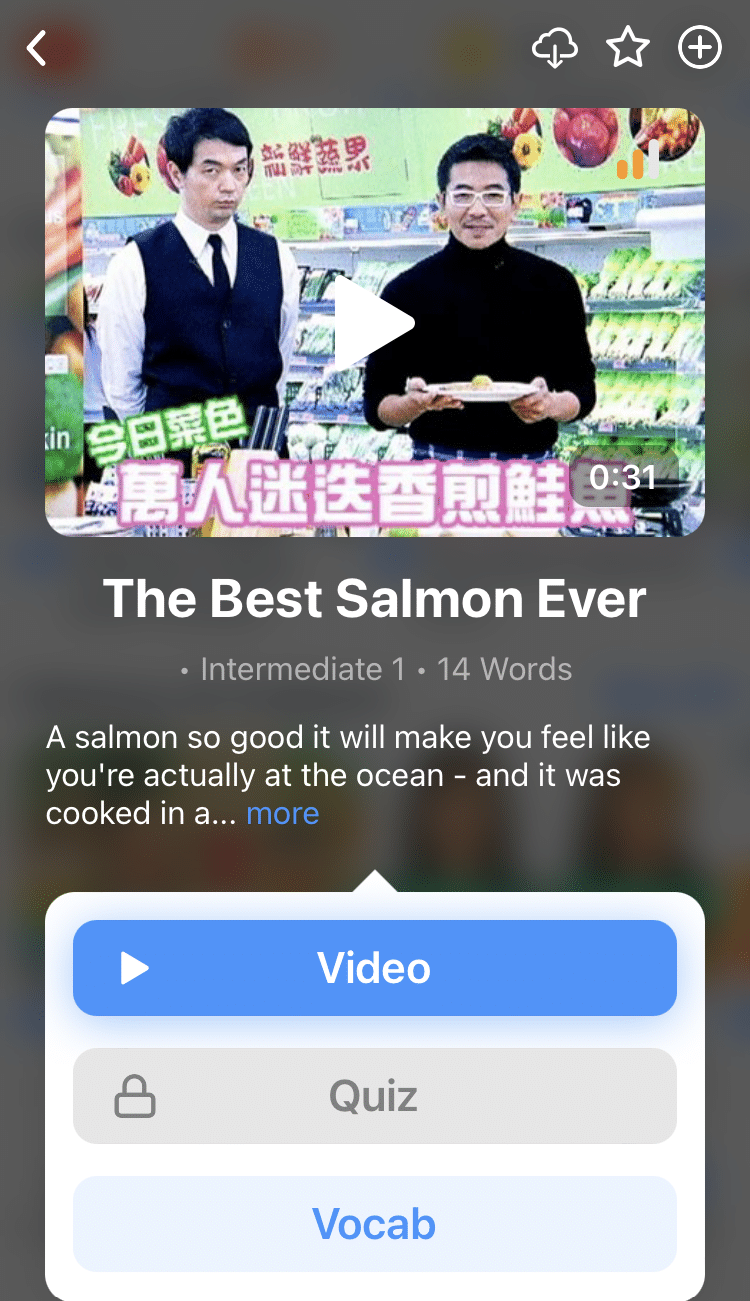

Using a resource, such as language learning program FluentU, can be a helpful way to familiarize yourself with Mandarin tones through authentic videos and audio clips.

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Learning with content from native speakers will help your ability to recognize and remember tones.

You can also practice with resources like Arch Chinese Mandarin Chinese Pinyin Tone Drill which will help you improve your listening skills through multiple-choice quizzes.

Exaggerate the tones

Whether you’re reading a passage or doing your tone pair drills, say the tones with gusto!

Giving that extra punch increases the chance of you actually remembering how the tones should sound, and the more you do this, the more you will improve your pronunciation.

If you want to hear the tones broken down to a simple level, you can also check out Learn Chinese with Litao’s video “Chinese finals “a, o, e, i, u, ü” & tones.”

This video lecture covers several aspects of the Chinese language:

- All of the simple vowel finals

- Five different tone basics

- Spelling rules for selected Chinese syllables and tone changes

There’s also a premium “full” version of this lesson that covers even more about tones, including all of the initial consonants, simple and compound vowels, spelling rules for syllables, tone changes and much more.

Slow down audio resources

Whether you’re listening to an audio course or clicking on the first YouTube video in Chinese you can find, slow the audio down so you can better identify tones (and, if you want to go the extra mile, repeat them out loud).

Podcasts are one of the best resources to use for this exercise, and you can always adjust their speed. In fact, there are plenty of podcasts specifically designed for Mandarin learners, such as the Slow Chinese podcast, where the speakers talk at a slower rate and use relatively simple vocabulary.

Use tone pairs in your own sentences

Practice talking to yourself out loud, pronouncing each tone to the best of your ability. Since each word has its own tone, you’ll need to get used to pronouncing multiple tones for just one sentence.

It might seem like a daunting task at first, but it’s not impossible, and hearing your voice make those beautiful, melodic Chinese sounds is quite satisfying.

Mark each tone with a different color

For those visual learners out there, a mnemonic device that might help is color coding. When a text is composed of so many different characters and sentences, tones can be tough to keep up with.

To make sure you’re reading the text correctly, you can assign each tone a different color, marking each character with the corresponding tone in order to read the passage correctly and fluently.

Remember that this strategy might not work for everyone, so don’t spend time highlighting or marking characters if you don’t find this kind of visual aid helpful.

Always have a dictionary

Pocket dictionaries, albeit a bit of a hassle to carry around, are really handy for those emergency situations where the person you’re talking to hasn’t got a clue what you’re trying to ask. Having that dictionary will help you correct yourself, shed clarity on the situation and hopefully you won’t be making the same mistake twice.

Of course, a physical dictionary isn’t absolutely necessary for moments like this, as there are a whole bunch of apps, from offline dictionaries and free resources for getting the tones right that you can rely on.

You can also use an app like Pleco, which functions as an integrated dictionary, document reader and flashcard system with handwriting input, so it’s fully equipped to assist you with any of your translation needs.

And that’s all there is to Chinese tones!

You’re officially ready to dive in and start sounding like a native Mandarin speaker.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing...

If you want to continue learning Chinese with interactive and authentic Chinese content, then you'll love FluentU.

FluentU naturally eases you into learning Chinese language. Native Chinese content comes within reach, and you'll learn Chinese as it's spoken in real life.

FluentU has a wide range of contemporary videos—like dramas, TV shows, commercials and music videos.

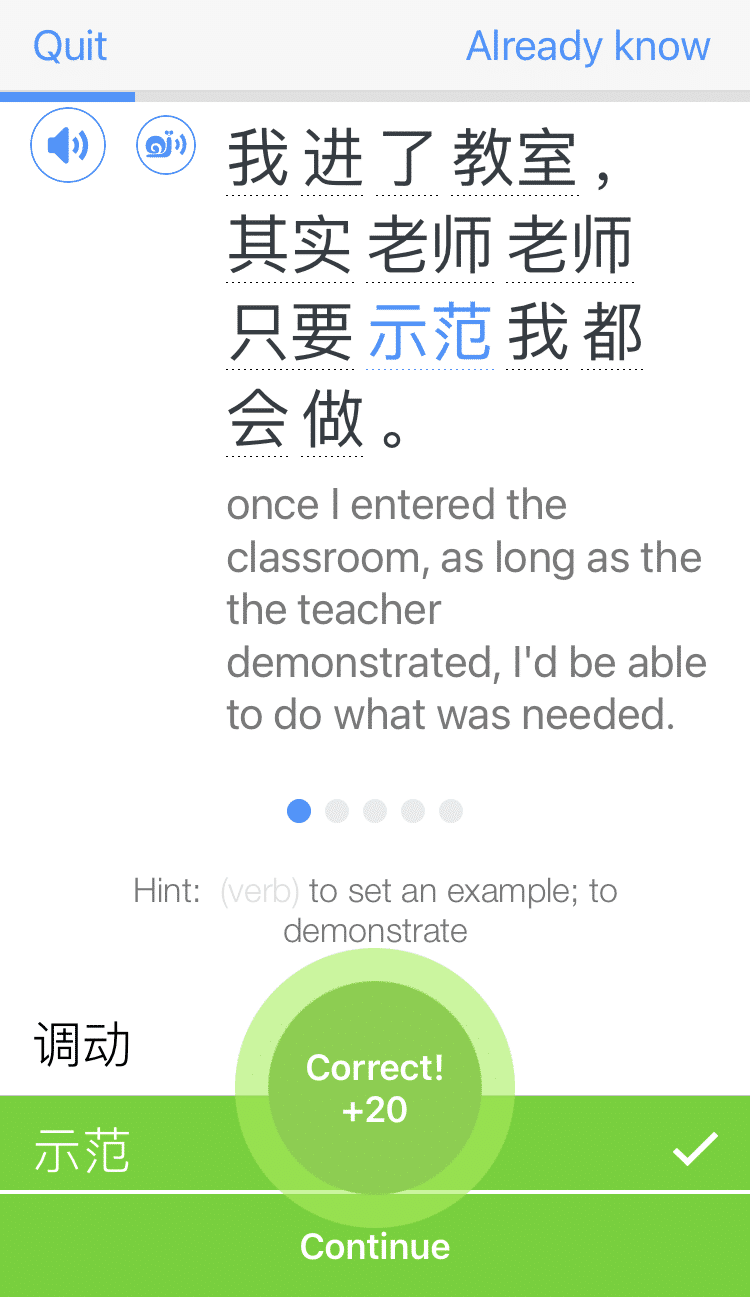

FluentU brings these native Chinese videos within reach via interactive captions. You can tap on any word to instantly look it up. All words have carefully written definitions and examples that will help you understand how a word is used. Tap to add words you'd like to review to a vocab list.

FluentU's Learn Mode turns every video into a language learning lesson. You can always swipe left or right to see more examples for the word you're learning.

The best part is that FluentU always keeps track of your vocabulary. It customizes quizzes to focus on areas that need attention and reminds you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. You have a 100% personalized experience.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)