German Possessive Pronouns vs. German Possessive Adjectives: The Complete Guide

Hast du meinen Hund gesehen? (Have you seen my dog?)

Dieser Hund ist meiner! (This dog is mine!)

Do you know the difference between these sentences?

The first uses the German possessive adjective meinen (my) to clearly express that I’m looking for the dog that belongs to me.

The second uses the German possessive pronoun meiner (mine) to complete replace the phrase “my dog,” while still expressing that the dog belongs to me.

Confused? Don’t be!

In this post, you’ll learn exactly how to form and take ownership of German possessive adjectives and German possessive pronouns in your own German sentences, plus plenty of other useful tips and tricks.

Contents

- Possessive Adjectives vs. Possessive Pronouns: What’s the Difference?

- Identify the Correct Possessive Stem

- German Possessive Adjectives

- German Possessive Pronouns

- How to Practice German Possessive Pronouns

- Why Learn German Possessive Pronouns?

- And One More Thing...

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Possessive Adjectives vs. Possessive Pronouns: What’s the Difference?

While both grammatical terms show possession, they are in fact different parts of speech: one is a pronoun while the other is an adjective. And, just like their English counterparts, pronouns replace nouns while adjectives describe those nouns.

In German, the endings for both terms are similar, as you’ll see, but that doesn’t mean they can be used interchangeably. Remember this distinction as you further develop your German grammar skills.

Identify the Correct Possessive Stem

The first step in constructing the correct possessive pronoun or adjective is choosing which pronoun stem you’ll build from. The following is a list of the pronoun stems you’ll use in the nominative case:

| German | English |

|---|---|

| mein | my/mine |

| dein | your/yours |

| sein | his |

| ihr | her/hers |

| sein | its |

| unser | our/ours |

| euer | your/yours (you plural) |

| ihr | their/theirs |

| Ihr | your/yours (you formal) |

Now we’ll go over each one in more detail. The basic pronoun for each possessive is included in parentheses for reference.

mein (ich) — my/mine (I)

Mein is the stem you’d use if you were trying to translate the following sentence, using the first person:

Ich habe einen kleinen Hund. Dieser Hund ist meiner.

(I have a small dog. This dog is mine.)

The correct possessive pronoun, therefore, is the one that corresponds to the owner of the noun being replaced, but also shows the case, gender and number of the noun, too.

“Meiner” shows that the noun, der Hund (the dog), is in the nominative case, masculine and singular via the -er ending to mein, which shows that the noun belongs to the subject “ich.”

We could say, “I have a small dog. This dog is my dog.” In the example above, however, the possessive pronoun “mine” replaces the entire “my dog” phrase. That’s why we can say, “This dog is mine” (“Dieser Hund ist meiner“)—the pronoun meiner replaces the noun mein Hund altogether.

dein (du) — your/yours (you singular)

Similarly, take the following example:

Du hast einen kleinen Hund. Dieser Hund ist deiner.

(You have a small dog. This dog is yours.)

Since the subject “you” owns the dog, we choose dein as the possessive pronoun stem. We again use the ending -er on the pronoun stem because the noun being replaced (der Hund) hasn’t changed from the last example. Only the ownership changes, from “I” (ich) to “you” (du).

sein (er) — his (he)

Er hat einen kleinen Hund. Dieser Hund ist seiner.

(He has a small dog. This dog is his.)

ihr (sie) — her/hers (she)

Sie hat einen kleinen Hund. Dieser Hund ist ihrer.

(She has a small dog. This dog is hers.)

sein (es) — its (it)

You probably won’t use the es form a lot, but it’s easy enough to remember—it’s the same as er—so the possessive here is seiner. That means you don’t have to memorize an extra pronoun!

unser (wir) — our/ours (we)

Wir haben einen kleinen Hund. Dieser Hund ist unserer.

(We have a small dog. This dog is ours.)

euer (ihr) — your/yours (you plural)

Ihr habt einen kleinen Hund. Dieser Hund ist eurer.

(You (all) have a small dog. This dog is yours.)

ihr (sie) — their/theirs (they)

Sie haben einen kleinen Hund. Dieser Hund ist ihrer.

(They have a small dog. This dog is theirs.)

Ihr (Sie) — your/yours (you formal)

Sie haben einen kleinen Hund. Dieser Hund ist Ihrer.

(You have a small dog. This dog is yours.)

German Possessive Adjectives

First we’re going to go over how to choose the right possessive adjective to put in front of your noun, as in: That’s my pen.

Keep those possessive stems in mind! You’ll need to know your base to determine the correct ending.

Here’s a chart of all the possible possessive adjective endings:

| Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | (none) | -e | (none) | -e |

| Accusative | -en | -e | (none) | -e |

| Dative | -em | -er | -em | -en |

| Genitive | -es | -er | -es | -er |

Important notes:

- If the chart says (none), you will simply use the possessive stem as is.

- The possessive stem euer drops the e after the u when it takes an ending (e.g., the singular feminine nominative form is euer + e = eure, while the singular neuter nominative does not take an ending and so is simply euer).

Now let’s take a closer look at exactly how to determine your possessive adjective ending.

Determine the Gender

In German, nouns are classed as either masculine, feminine or neuter. The noun’s gender dictates which form your possessive adjective will take.

Here’s a sentence with the possessive adjective “my” for each gender:

- Masculine:

Mein Hund ist groß.

(My dog is big.) - Feminine:

Meine Mutter heißt Anna.

(My mother is called Anna.) - Neuter:

Mein Lamm isst gerne Gras.

(My lamb likes to eat grass.)

It’s important to point out that all possessive adjectives follow this same pattern. That makes this one of the easier parts of German to learn!

So if you wanted to say: “Her mother is called Anna” the ihr would follow the same pattern as mein and have an e added to it because “mother” is a feminine noun:

Ihre Mutter heißt Anna.

(Her mother is called Anna.)

Determine the Case

The noun’s gender is not the only thing you need to pay attention to. In order to select the correct form for your possessive adjective, you also need to know which case it needs to be in.

The Nominative Case

This is the easiest case to master, as the possessive adjectives will not change—they’re exactly what you learned above. The examples in the previous section are all in the nominative case as well.

Think of the nominative case as the “naming” case. It’s used when we’re simply naming something. The subject of the sentence is always in the nominative case, like this:

Dein Computer ist kaputt.

(Your computer is broken.)

The nominative case also follows the verb ist (is):

Das ist sein Kaffee.

(That is his coffee.)

And let’s not forget about plural nouns, which are all treated the same regardless of the gender. For plural nouns in the nominative case, the possessive adjective just gains an -e ending.

Meine Kinder sind brav.

(My children are well-behaved.)

The Accusative Case

The direct object of the sentence—the thing that receives the action—takes the accusative case. Handily, the endings for feminine, neuter and plural nouns stay the same in this case, but for masculine nouns, the ending becomes -en, as shown here:

Kannst du meinen Computer reparieren?

(Can you fix my computer?)

Ich habe deinen Bruder gesehen.

(I saw your brother.)

Wir haben unseren Hund adoptiert.

(We adopted our dog.)

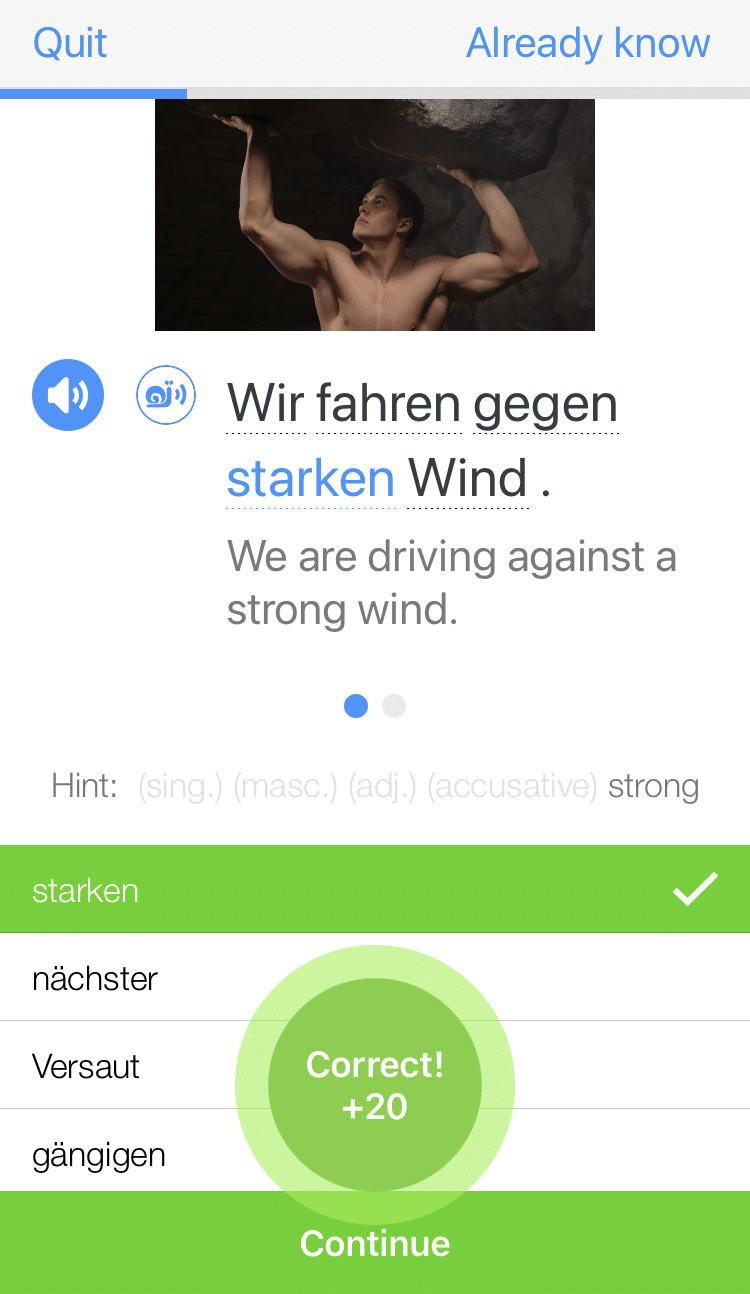

Further, there are certain German prepositions that require the following noun to be in the accusative case, including durch (through), entlang (along/alongside), für (for), gegen (against), ohne (without), um (at/around/for) and wider (against).

Das ist für meinen Vater.

(That is for my father.)

Ich gehe ohne meinen Freund.

(I’m going without my boyfriend.)

There are also some prepositions that take either the accusative or dative case, depending on what exactly is going on. If there’s movement in the sentence and it can answer the question wohin? (where to?), then it takes the accusative.

These prepositions include an (on), auf (up/on), hinter (behind), in (in), neben (near), über (over), unter (unter), vor (before) and zwischen (between).

Let’s look at some examples where there is movement onto the masculine nouns der Garten (the garden) and der Schoss (the lap).

Die Katze des Nachbarn ist in unseren Garten geklettert.

(The neighbor’s cat climbed into our garden.)

Ich habe mich auf seinen Schoss gesetzt.

(I sat down on(to) his lap.)

The Dative Case

The dative case can be quite difficult to learn because all of the possessive adjectives change their endings. It’s a super useful case to know, though—once you’re able to use it, you’ll notice that you can say a whole lot more!

The dative denotes the indirect object of the sentence. The indirect object is what receives the direct object.

So, if you give a present to your friend: the present is the direct object, and your friend is receiving it, so they are the indirect object.

The dative case affects possessive adjectives like this:

- Masculine nouns add an -em to their possessive adjectives.

Ich habe meinem Vater eine Krawatte gekauft.

(I bought my father a tie.) - Feminine nouns add an -er ending.

Du solltest deiner Freundin die Wahrheit sagen.

(You should tell your girlfriend the truth.) - Neuter nouns also take an -em ending, like the masculine form.

Er gibt seinem Baby einen Schnuller.

(He gives his baby a pacifier.)

Like I mentioned above, there are also dative-specific prepositions: aus (from/out), außer (besides), bei (near/by/with/on), mit (with), nach (to/after), seit (since), von (from/of), zu (to) and gegenüber (opposite).

Ich gehe mit meinen Freunden ins Kino.

(I’m going to the movies with my friends.)

Ich fahre zu meinem Opa.

(I’m driving to my grandfather’s.)

And remember the two-way prepositions I mentioned in the last section? This time, remember that if they’re used in a sentence without any movement, they take the dative case.

Ich wohne neben ihrem Bruder.

(I live next to her brother.)

Du kannst in seinem Bett schlafen.

(You can sleep in his bed.)

The Genitive Case

This case is typically used to show possession. For possessive adjectives in the genitive case, masculine and neuter nouns take an -es ending. You also need to add an -(e)s ending on to the noun itself when it is masculine or neuter:

Der Hund deines Onkels schläft.

(Your uncle’s dog is sleeping.)

Der Feind meines Feindes ist mein Freund.

(The enemy of my enemy is my friend.)

And for the feminine, just add -er to your possessive adjective:

Die Tasche seiner Frau ist rot.

(His wife’s bag is red.)

Note that there are also certain prepositions that require the genitive case.

These prepositions are: während (during), trotz (despite), statt/anstatt (instead of), wegen (because of), innerhalb (within/inside of), außerhalb (outside of), jenseits (beyond/across/over) and diesseits (here/now).

Ich wohne außerhalb des Stadtzentrums.

(I live outside of the city center.)

Was ist während meiner Abwesenheit passiert?

(What happened during my absence?)

German Possessive Pronouns

Now, we’ll switch gears and cover everything you need to know about choosing the correct possessive pronoun to replace the noun in your sentence, as in: That cute bag is hers.

Again, you’ll need to make sure you know which possessive stem you’re using.

Here’s a chart to help you figure out your possessive pronoun endings.

| Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | -er | -e | -es / -s | -e |

| Accusative | -en | -e | -es / -s | -e |

| Dative | -em | -er | -em | -n |

| Genitive | -es | -er | -es | -r |

Important notes:

- Once again, the stem euer drops the e after the u when you add an ending (e.g., the singular neuter nominative form would be euer + e + s = eures).

- You may see unser forms drop the e after the s. So the singular neuter nominative form would be unser + e + s, which may be unseres or unsres.

Determine the Gender

Like before, you’ll need to figure out the gender of the relevant noun.

Consider this previous example: “I have a small dog. This dog is mine.”

The object is “the dog” or der Hund in German. The noun being replaced dictates the possessive pronoun’s ending. This is a masculine noun, so you’d need a masculine ending.

Determine the Case

Now, again, determining the correct case will finalize your possessive pronoun ending.

The Nominative Case

All of the example sentences above that describe “this dog” as belonging to someone are in the nominative case. That’s why “I have a small dog. This dog is mine.” becomes “Ich habe einen kleinen Hund. Dieser Hund ist meiner.” in German.

Here’s a quick look at the nominative possessive pronoun endings for each gender:

- Masculine nouns such as der Hund (the dog) take an -er ending.

Dieser Hund ist meiner.

(This dog is mine.) - Feminine nouns such as die Katze (the cat) take an -e ending.

Diese Katze ist meine.

(This cat is mine.) - Neuter nouns such as das Haus (the house) take an -es ending, which may or may not include that middle -e-.

Dieses Haus ist meines/meins.

(This house is mine.)

If the noun being replaced is plural, simply add an -e ending to the pronoun stem. For example, “These stories are ours” would translate to, “Diese Geschichten sind unsere.”

The Accusative Case

In the accusative case, there are a few changes. Let’s look at a new example sentence:

Hast du einen Kuli? Ich habe meinen verloren.

(Do you have a pen? I’ve lost mine.)

Notice that the meinen possessive pronoun replaces the phrase einen Kuli. Though pen is masculine (der Kuli), we can’t use the nominative meiner in this situation.

That’s because the subject (ich) has lost their pen, so the pen is the direct object and therefore in the accusative case. So you’ll choose the -en ending to reflect this.

In summary:

- Masculine: -en ending

- Feminine: -e ending

- Neuter: -(e)s ending

- Plural: -e ending

The accusative case can also be indicated by accusative prepositions. These types of prepositions are another sign letting you know which case—and corresponding endings—to choose.

For example:

Wir essen mit meinem Vater aber ohne seinen.

(We eat with my father but without his.)

The Dative Case

As you know from above, the dative case incorporates an indirect object into the sentence. Or, this case can be indicated by a dative verb and/or dative preposition.

For example, let’s say you’re expressing that “his” parents aren’t here, so you’re eating with “yours” (meaning “your parents”). In German, this would be:

Seine Eltern sind nicht hier, also essen wir mit meinen.

The ending on mein must be in the dative case, so you’ll take mein + e + n to get the correct form meinen.

Dative possessive pronoun endings are as follows:

- Masculine: -em ending

- Feminine: -er ending

- Neuter: -em ending

- Plural: -en ending

Remember, dative verbs and prepositions will trigger this ending change as well.

The Genitive Case

The last case, the genitive, is all about showing possession.

Here’s exactly what that means:

- der Hut meines Vaters is “the hat of my father” or “my father’s hat”

- die Pizza deiner Schwester is “the pizza of your sister” or “your sister’s pizza”

- der Eingang seines Hauses is “the entrance to his house”

- die Geschichte ihrer Erfolge is “the story of their successes”

As you can see, the endings are unique to the genitive case.

Both masculine and neuter nouns take an -es ending when it comes to the possessive pronoun and an –(e)s ending for the possessor. The “e” is added to the end of nouns when necessary, just as with the possessive words.

Feminine and plural nouns add an -er ending to the possessive pronoun.

There are also the genitive prepositions. Like accusative and dative prepositions, these parts of speech will make the objects they describe change to the genitive case.

More examples of genitive prepositions include während (during), trotz (despite), (an)statt (instead of), wegen (because of), innerhalb (inside), außerhalb (outside), jenseits (on the other side) and diesseits (on this side of).

A special note: Alternatively, some Germans have come to accept using the singular “s” for possessives, albeit without the apostrophe. That means you can say Annies Haus (Annie’s house) or Raphaels Hund (Raphael’s dog) and even Sams Auto (Sam’s car).

How to Practice German Possessive Pronouns

If you’re looking to practice your newfound skill of owning possessive pronouns (or adjectives!), we’ve got the resources for you.

Quizlet offers a series of exercises and quizzes on possessive pronouns. Whether you’ve got a few moments or a few hours, see what you can accomplish with these practice exercises and quizzes.

German with Laura’s full tables tackle every possible possessive pronoun and possessive adjective (though these may seem a bit overwhelming!).

Why Learn German Possessive Pronouns?

In German, possessive pronouns are part of the larger grammar system, which governs the language as a whole. Knowing what possessive pronouns are and how to properly use them is just one way to play by the rules—German rules, that is.

It’s critical to have the correct possessive pronoun for the object you’re describing since the pronoun will replace the object.

For example, if you were to describe a masculine object while using the feminine possessive pronoun to replace it, you could create lots of confusion. This is especially true if there’s a feminine object in the sentence that you didn’t mean to refer to.

Let’s say I were to tell you, “There is a dog and a cat. The cat is mine.” In German, you would say, “Es gibt einen Hund und eine Katze. Die Katze ist meine.”

If you then wanted to tell me something about the dog but you referred to the cat, things could get messy.

For instance, if you said, “Meine bellt lauter” (“Mine barks louder”), you’d technically be talking about the cat. And cats don’t typically bark.

This is because “Meine,” using the -e ending, would refer to die Katze (the cat). The proper possessive pronoun would be “meiner” since you want to refer to the masculine noun mein Hund. The correct pronoun would use the -er ending to denote a masculine noun.

Circling back to grammar—and away from the drama—possessive pronouns can aid you in identifying cases and perfecting adjective endings. Knowing the correct adjective ending can be a pain to memorize, but with possessive pronouns, you’ll always have a hint.

And all of this gets you one step closer to being a better German speaker and becoming fluent!

There you have it! Enough said about German possessive pronouns and adjectives.

Once you practice these forms, you can use them with confidence in your German conversations and wow your German friends.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing...

Want to know the key to learning German effectively?

It's using the right content and tools, like FluentU has to offer! Browse hundreds of videos, take endless quizzes and master the German language faster than you've ever imagine!

Watching a fun video, but having trouble understanding it? FluentU brings native videos within reach with interactive subtitles.

You can tap on any word to look it up instantly. Every definition has examples that have been written to help you understand how the word is used. If you see an interesting word you don't know, you can add it to a vocabulary list.

And FluentU isn't just for watching videos. It's a complete platform for learning. It's designed to effectively teach you all the vocabulary from any video. Swipe left or right to see more examples of the word you're on.

The best part is that FluentU keeps track of the vocabulary that you're learning, and gives you extra practice with difficult words. It'll even remind you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)