Imparfait vs. Passé Composé: What Are The Differences?

If you pay attention, you’ll find yourself using the past tense several times throughout your day.

The past tense in French will come up often and what can be difficult for French learners is that there are different tenses to talk about the past and each tense describes a certain kind of action that happened.

In this post, we’ll show you what you need to know about French’s two main past tenses: the imparfait (imperfect tense) and passé composé (perfect tense). You’ll see how to form them and when to use them with examples.

Contents

- How to Form and Use the Imparfait

- How to Form and Use the Passé Composé

- How to Use the Imparfait and Passé Composé Together

- Where to Practice the Imparfait and Passé Composé

- And one more thing...

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

How to Form and Use the Imparfait

The imparfait, or imperfect past, is used to describe conditions and continual/repeated actions, which we’ll explain in greater depth later on.

First, let’s look at how to form the imparfait.

Conjugating (Most) Verbs in the Imparfait

The imparfait isn’t difficult to conjugate. All verbs follow the same pattern, with the sole exception of être (to be), which we’ll cover separately below.

That means that whether the ending of the verb’s infinitive is -re, -ir or -er, the endings are the same.

You can check out this video to learn how to conjugate -er verbs in French:

All we have to do is simply:

- Identify the verb’s nous form.

- Remove the -ons ending from the nous form.

- Add the ending for the appropriate subject, following the pattern below.

Je (I): -ais

Tu (You): -ais

Il/Elle/On (He/She/One): -ait

Nous (We): -ions

Vous (You): -iez

Ils/Elles (They): -aient

Not quite sure what we mean?

Let’s say you want to describe one of your hobbies from high school—playing violin. The verb you need here is jouer (to play), as in, je joue du violin (I play violin).

Following the steps above, we would get:

- The nous form for the verb jouer is jouons (we play).

- Removing the -ons ending from that form, we come up with jou.

- Since you’re talking about yourself, the subject is je. That means we must add the ending -ais.

Thus, the verb form we get is jouais and our new sentence is:

Au lycée, je jouais du violin. (In high school, I played the violin.)

Starting to get the idea? Let’s take a look at what the imparfait for other common verbs would be.

For regarder (to watch), all the forms would be:

| Je regardais | I watched |

| Tu regardais | You watched |

| Il/Elle/On regardait | He/She/One watched |

| Nous regardions | We watched |

| Vous regardiez | You watched |

| Ils/Elles regardaient | They watched |

Similarly, the full imparfait conjugation for devenir (to become) is:

| Je devenais | I became |

| Tu devenais | You became |

| Il/Elle/On devenait | He/She/One became |

| Nous devenions | We became |

| Vous deveniez | You became |

| Ils/Elles devenaient | They became |

Now you’re well on your way to smoothly forming the imparfait. You may need to think about it at first, but as you practice, it’ll become more natural.

Conjugating Être in the Imparfait

To conjugate the exception verb être (to be), instead of modifying the nous form (sommes), we modify the stem ét-.

Then, you can use the same endings as above.

The full conjugation would look like:

| J'étais | I was |

| Tu étais | You were |

| Il/Elle/On était | He/She/One was |

| Nous étions | We were |

| Vous étiez | You were |

| Ils/Elles étaient | They were |

When to Use the Imparfait

So, now we know how to form the imparfait, but how do we know when to use it?

There are four main situations in which we’ll use the imparfait:

- Actions taking place over a period of time

- Conditions

- Repeated/habitual actions

- Physical descriptions

Actions taking place over a period of time

If a certain action covers a significant period of time, we’ll use the imparfait because it’s a continuous action. This contrasts with the passé composé, which as you’ll see later in this post, describes a single, completed action.

Let’s look at a couple of examples of what we’re talking about.

- Robespierre était la tête de la Régime de Terreur. (Robespierre was the head of the Reign of Terror.)

We use the imparfait form of être because the Reign of Terror, unfortunately, lasted almost a year (September 1793 to July 1794) and claimed many lives.

- Quand les nazis occupaient la France, le marché noir était répandu. (When the Nazis occupied France, the black market was prevalent.)

Here, we use the imparfait for both of the verbs because both of these events took place over a period of time. The Nazis occupied France for four years (1940 to 1944) and the black market flourished throughout this period.

Conditions

We use the imparfait to describe conditions or the backdrop to the main action. This is one reason why the imparfait and passé composé are often used in the same passage or phrase—the imparfait sets up the main action by giving the background, while the passé composé is used for the primary, completed action.

The biggest example of a condition is weather, but could include other kinds of conditions, such as age.

- Il neigeait beaucoup hier soir. (It snowed a lot last night.)

This one’s pretty straightforward. Since snow describes the weather, we use the imparfait.

- Quand elle avait huit ans, elle visitait sa grand-mère tous les week-ends. (When she was eight years old, she visited her grandmother every weekend.)

We use the imparfait because the fact that she was eight years old is a condition that sets up the rest of the sentence. We put visiter in the imparfait because it’s a habitual/repeated action (which we’ll talk about next). She visited her grandmother, not just once, but on a regular basis.

Repeated/habitual actions

This might be the most common use of the imparfait. When we’re describing a routine we used to practice, a habit we used to have or anything else that was repeated, we’ll use the imparfait.

- Quand ils habitaient en France, ils visitaient le parc tous les samedis. (When they lived in France, they visited the park every Saturday.)

Since they lived in France over a period of time, habiter is in the imparfait, and since the action of going to the park was part of a routine, visiter must also be put in the imparfait.

- Pendant l’été, tu allais à la plage tous les week-ends. (During summer, you went to the beach every weekend.)

Because you went to the beach every weekend (living the dream!) we use the imparfait.

Physical descriptions

This one’s also rather simple. Whether it’s hair color, height or clothing, we use the imparfait when we describe how a person or thing was.

- Elle avait les cheveux bouclés. (She had curly hair.)

Hair is obviously a physical trait, so we use the imparfait.

- Vous portiez une robe rouge. (You wore a red dress.)

Similarly, clothing falls under physical description.

How to Form and Use the Passé Composé

The passé composé has two parts and does have a greater variety of forms than the imparfait. However, we don’t need to list and explain each of the uses for this tense, as it’s essentially used whenever the imparfait is not.

In other words, if the action in question doesn’t fall under one of the imparfait categories listed above, it’ll be in the passé composé.

Conjugating (Most) Verbs in the Passé Composé

Passé composé literally means “compound past.” This is because the tense is made up of two parts.

Here’s how you do it for the majority of verbs (as always, there are exceptions, which we’ll get to):

1. Identify the appropriate form of the verb avoir (to have) depending on your subject.

In case you need a quick review, here’s the avoir present conjugation:

| J'ai | I have |

| Tu as | You have |

| Il/Elle/On a | He/She has |

| Nous avons | We have |

| Vous avez | You have |

| Ils/Elles ont | They have |

2. Add the participe passé (past participle). Here’s the tricky part. The past participle is different for different kinds of verbs. Memorizing them will take practice, but we’ll walk you through the most common patterns and show you how to use them.

For regular verbs ending in -er, we simply remove the -r from the infinitive and add an accent to the e. For example, the past participle for manger (to eat) is mangé. The past participle for jouer (to play) is joué.

For regular verbs ending in -re, we remove the whole -re ending from the infinitive and replace it with -u. Thus, attendre (to wait for/expect) becomes attendu and entendre (to hear) becomes entendu.

For regular -ir verbs, all we have to do is remove the -r from the infinitive. So, finir (to finish) becomes fini and choisir (to choose) becomes choisi.

Of course, some verbs just have to be special, and their past participles don’t follow any particular pattern. The main three include:

Être (to be) becomes été.

Avoir (to have) becomes eu.

Faire (to do/to make) becomes fait.

If you come across other irregular verbs that don’t seem to fall into any of these categories, or just want to double-check, try out Reverso’s conjugation tool. You can type in a verb and they’ll show you every possible conjugated form, including the participe passé.

Conjugating “Dr. Mrs. Vandertramp” Verbs

There are always those few rogue verbs that just feel like breaking the rules. For this small group, known among many French teachers and students as “Dr. Mrs. Vandertramp” verbs, we use the conjugated form of être instead of avoir like above.

Why this strange name? It’s a mnemonic to help you remember the verbs in this group:

Devenir (To become)

Revenir (To come back)

Monter (To go up)

Retourner (To return)

Sortir (To go out)

Venir (To come)

Aller (To go)

Naître (To be born)

Descendre (To go down)

Entrer (To enter)

Rentrer (To go home/to return)

Tomber (To fall)

Rester (To remain)

Arriver (To arrive)

Mourir (To die)

Partir (To leave)

…Okay, one more! Passer par (to pass) also takes être in the passé composé.

So for example, here’s how you would use these verbs in context with the passé composé:

Je suis rentré(e) chez moi à 2 heures du matin. (I went home at 2:00 in the morning.)

Note that when using verbs that take être in the passé composé, the past participle must agree with the gender of the subject.

When to Use the Passé Composé

Good news! The function for the passé composé is so much simpler than the imparfait.

While the imparfait is used for specific situations, the passé composé, as mentioned earlier, simply describes a completed action. It’s essentially used to form the past tense whenever the imparfait isn’t employed.

A few simple examples include:

J’ai pris un examen à l’école aujourd’hui. (I took a test at school today.)

Ils ont acheté une pizza pour le dîner. (They bought a pizza for dinner.)

Avant le déjeuner, vous avez pratiqué le violin. (You practiced the violin before lunch.)

What if you want to say that something didn’t happen? The proper word order is:

ne + conjugated form of avoir (or être) + pas + past participle

Let’s try a couple examples:

Je n’ai pas assisté au match. (I didn’t attend the match.)

Pourquoi tu n’as pas fait tes devoirs? (Why didn’t you do your homework?)

How to Use the Imparfait and Passé Composé Together

As we mentioned above, these two tenses are regularly used together, in the same passage or even the same sentence. If you read a short story in French or listen closely to a conversation, you’ll notice both tenses being juggled.

Perfectly natural for native speakers—often a struggle for learners. But we’ll explain some examples.

Generally speaking, the imparfait will “set up” a certain condition or context, while the passé composé will complete the thought by supplying the main, finished action. Let’s take a look:

- Hier, quand il pleuvait, on a annulé le pique-nique. (Yesterday, when it rained, we cancelled the picnic).

The imparfait, in describing the weather (a condition), sets up the completed action of cancelling the picnic. Because it was raining, it was necessary to cancel the picnic.

- Il devenait fâché et m’a frappé. (He became angry and hit me.)

The imparfait describes how someone was and tells us that his anger was building up (taking place over a period of time). The passé composé tells us what that anger led to. In this case, unfortunately, it was violence.

- Elle a perdu sa tante quand elle avait dix ans. (She lost her aunt when she was ten years old.)

In this case, the main completed action comes first: her aunt died. Then we get details about the condition surrounding the aunt’s death—it happened when the girl was ten years old.

Where to Practice the Imparfait and Passé Composé

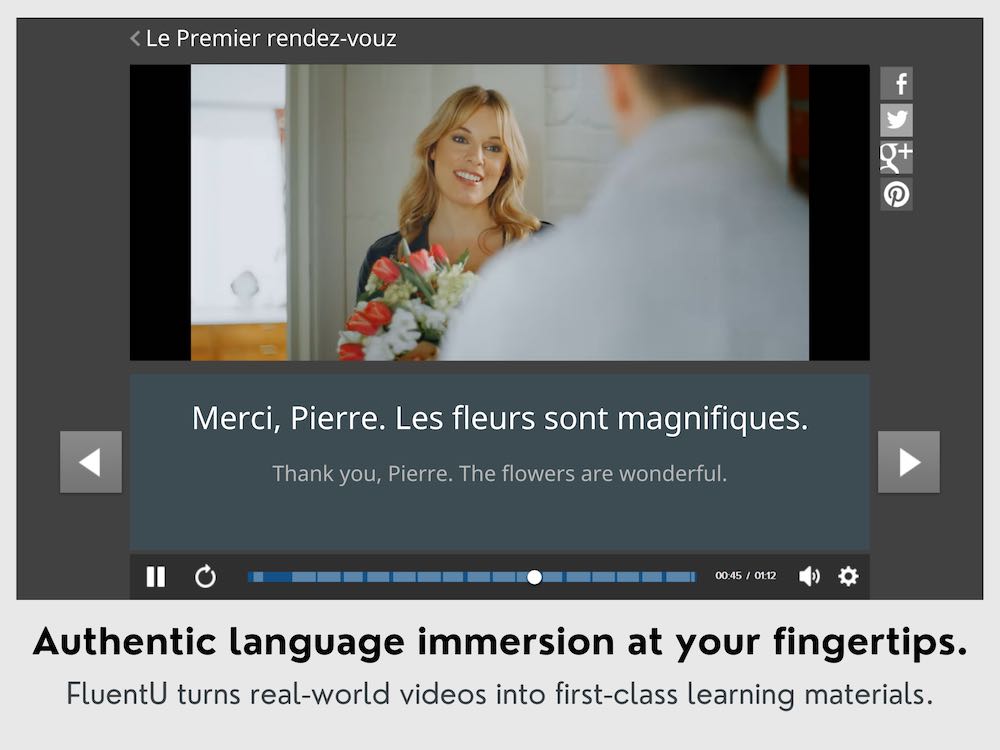

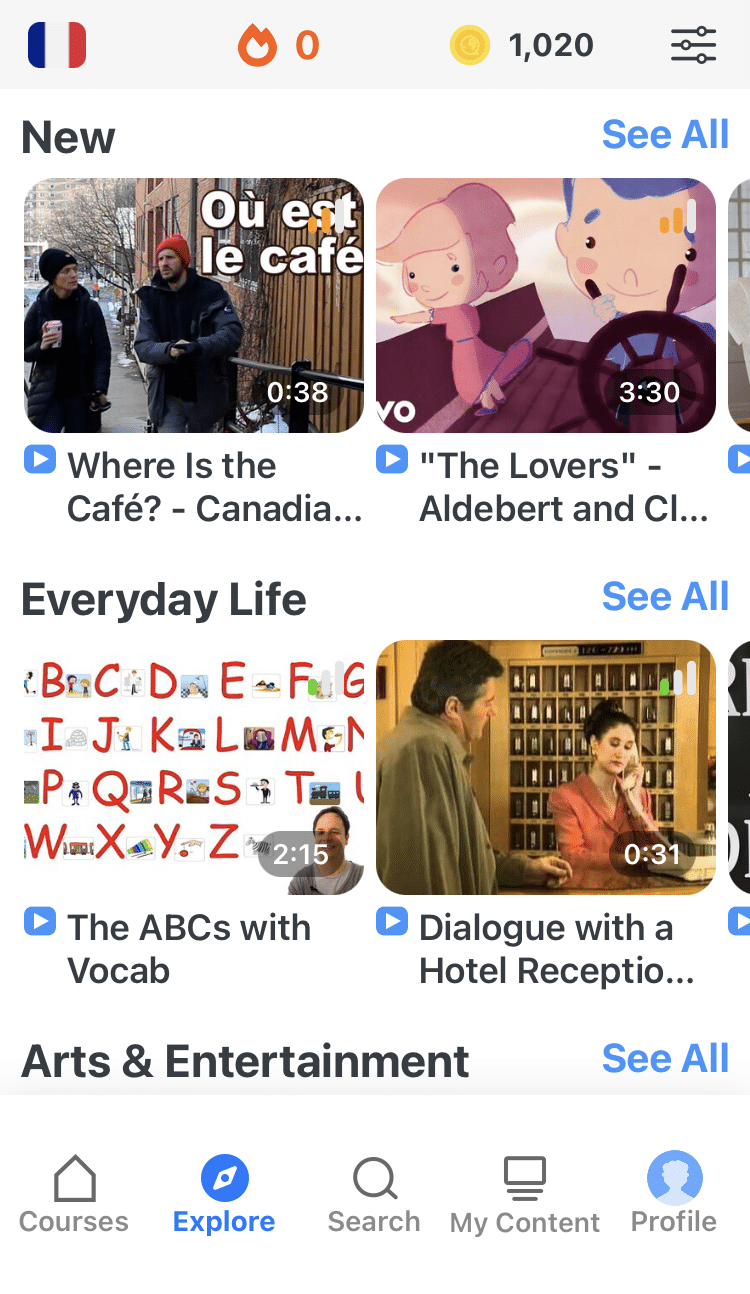

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

As with learning anything new about language, the key to mastery is practice. Here are some fun and useful options for applying the rules you just learned:

- Reading: When you read French text in the past tense, you’re sure to see a smooth mixture of imparfait and passé composé. As you see more and more when each is used and how they work together, your brain will begin to make connections and using them yourself will become much more natural.

For example, check out this cute and simple story, which seamlessly blends tenses. The page also shows you how certain adverbs often accompany a certain tense. For instance, tous les jours often signals the imparfait because it indicates a habit.

- Online exercises: Quia has a helpful quiz testing your ability to form these tenses and when to use them. ToLearnFrench has an exercise that has you conjugate verbs in the context of a passage, giving you yet another example of how these tenses work as a team.

Félicitations! (Congratulations!) You’re well on your way to speaking comfortably about the past in French. It does take practice, but we’ve given you the tools you need to build up your skills. Now you need simply to use them. Bonne chance! (Good luck!)

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And one more thing...

If you like learning French on your own time and from the comfort of your smart device, then I'd be remiss to not tell you about FluentU.

FluentU has a wide variety of great content, like interviews, documentary excerpts and web series, as you can see here:

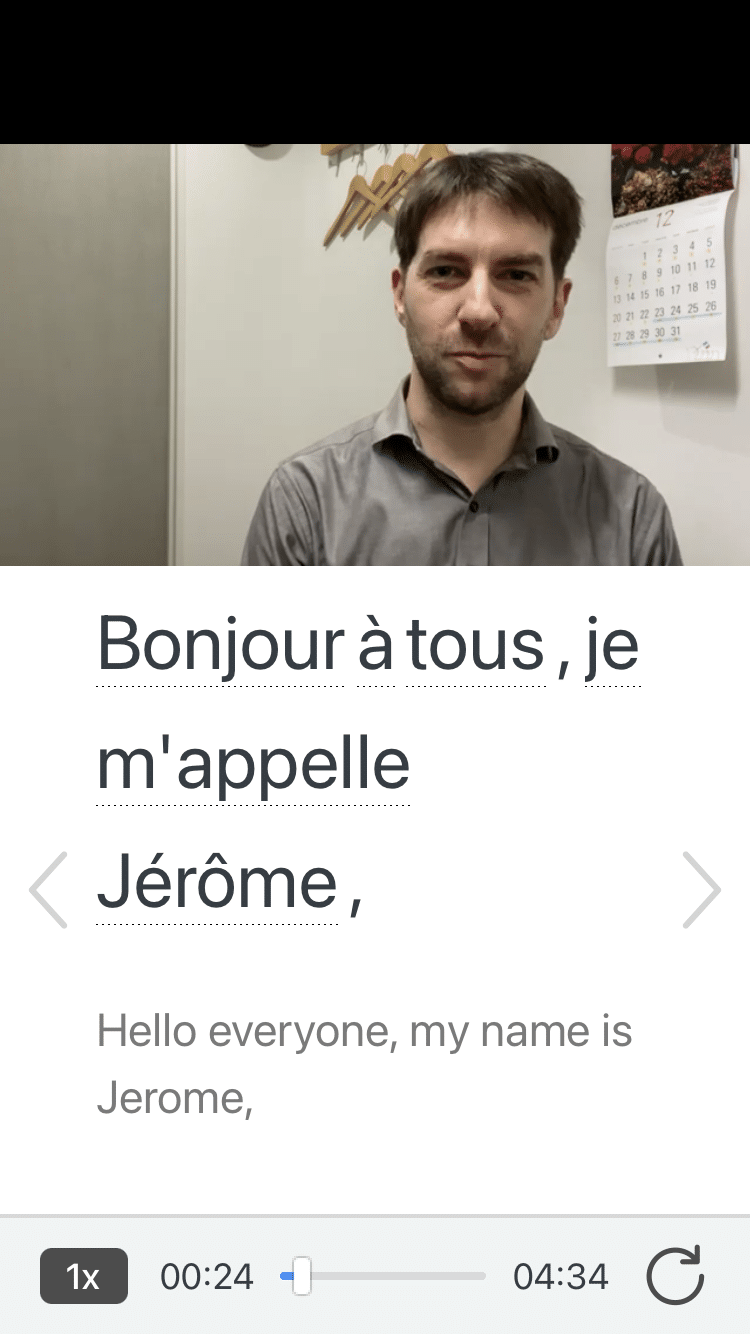

FluentU brings native French videos with reach. With interactive captions, you can tap on any word to see an image, definition and useful examples.

For example, if you tap on the word "crois," you'll see this:

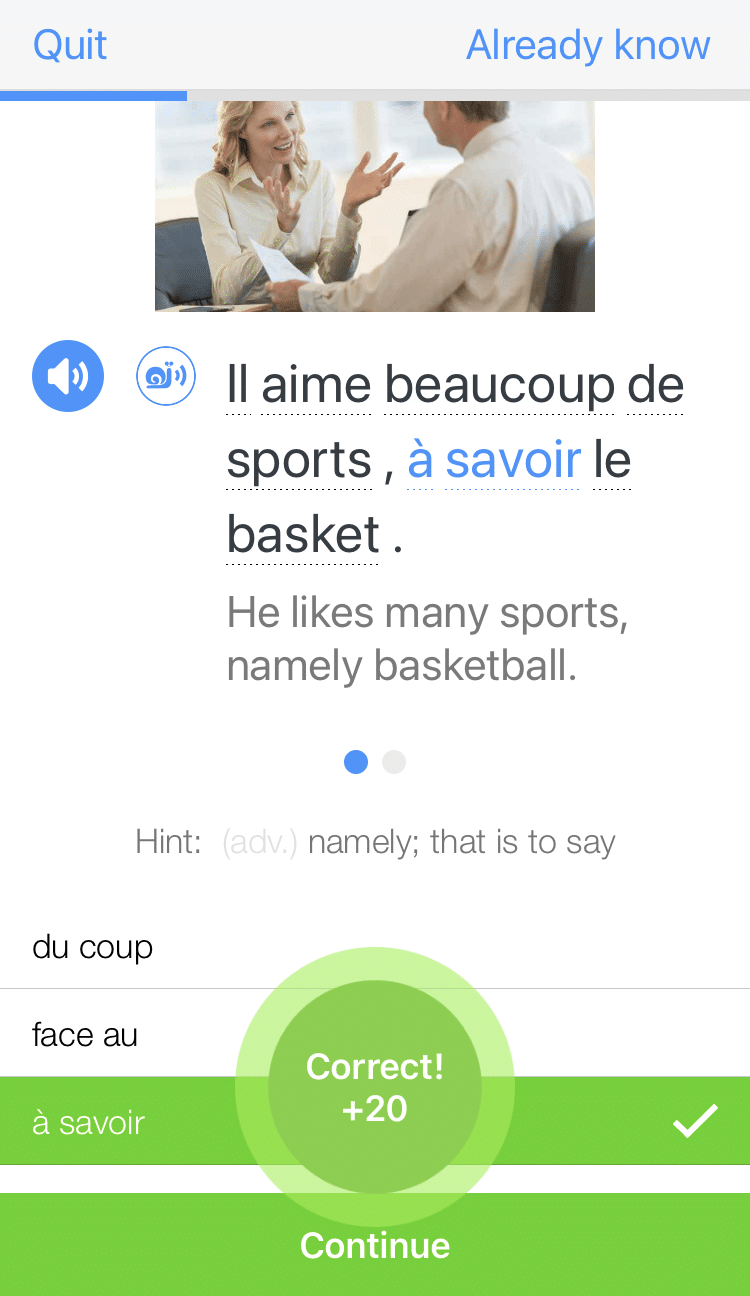

Practice and reinforce all the vocabulary you've learned in a given video with learn mode. Swipe left or right to see more examples for the word you’re learning, and play the mini-games found in our dynamic flashcards, like "fill in the blank."

All throughout, FluentU tracks the vocabulary that you’re learning and uses this information to give you a totally personalized experience. It gives you extra practice with difficult words—and reminds you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)