How Long Does It Take to Learn Chinese? The Honest (and Surprising) Truth

Figuring out how long it takes to learn Chinese depends on various factors—such as your native language, current level, experience with languages, etc.

And most importantly: your goal.

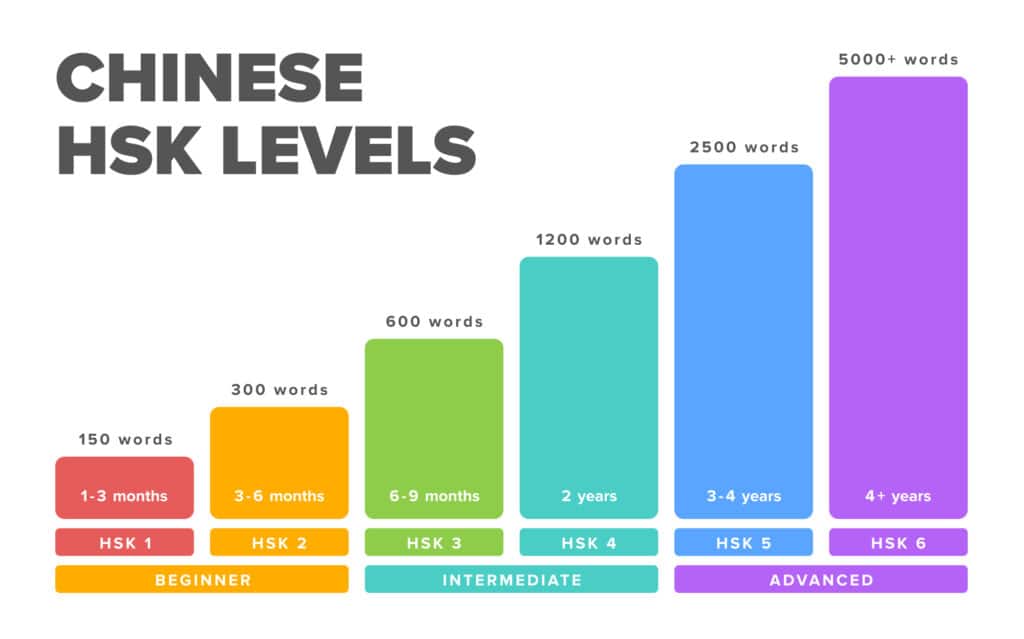

Becoming fluent and highly proficient in Mandarin Chinese (and passing the HSK Level 6) requires you to know 5,000 characters or more and takes four or more years.

Whereas reaching a conversationally fluent level (such as HSK Level 4) requires you to know about 1,200 characters and takes around two years.

In this post, we’ll discuss how long it takes to learn Chinese based on your goal fluency level and six key factors.

Contents

- The 5 Levels of Learning Chinese

- How Long It Takes to Learn Chinese (By Level)

- 6 Factors that Determine How Long It Will Take You to Learn Chinese

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

The 5 Levels of Learning Chinese

HSK is the official Chinese proficiency exam and stands for 汉语水平考试 (hàn yǔ shuǐ píng kǎo shì).

There are six levels. Level 1 is the lowest and Level 6 is the highest.

Each requires you to know a certain amount of characters.

The Foreign Service Institute has classified Mandarin Chinese as a Category 5 language—meaning it’s one of the most difficult languages to learn alongside Cantonese, Korean, Japanese and Arabic.

They’ve also broken down Chinese proficiency into five categories:

| Proficiency Level | Description |

|---|---|

| Elementary Proficiency | You can form basic sentences, including asking and answering questions. |

| Limited Working Proficiency | You're able to communicate at a basic level in a work and social environment. This level includes "small talk." |

| Professional Working Proficiency | You can perform most work tasks in Chinese, including participating in meetings and communicating with clients, superiors and coworkers. Your vocabulary is extensive at this level, but you might still not catch every word or informal nuances. |

| Full Professional Proficiency | This is the level you'll likely need if you're working for a Chinese company or one that communicates regularly with Chinese-speaking clients and investors. At this level, you can carry out both professional and casual conversations with ease. |

| Native/Bilingual Proficiency | You did it! You're full-on fluent in Chinese! Congratulations! |

To get to the fifth (most advanced) level, the FSI estimates it takes around 2,200 hours of active learning (approximately 88 weeks).

Another way to determine how long it will take you to learn Chinese is to consider how many characters you need to know to pass each HSK level.

How Long It Takes to Learn Chinese (By Level)

Lower Beginner Level (HSK 1) – 1 to 3 Months

HSK 1 is the most beginner level of Mandarin Chinese. To pass, you need to know 150 characters and some basic grammar points.

This can take anywhere from one to three months.

You can expect to achieve the HSK 1 level in one month if you learn 4-5 characters a day for 31 days. Studying 2-3 characters daily will get you there in 60 days, and 1-2 characters will get you there in 90 days.

Upper Beginner Level (HSK 2) – 3 to 6 Months

HSK 2 represents the upper beginner (or pre-intermediate) Chinese level. You need to know 300 characters total and learn some new basic grammar points.

This usually takes three to six months.

Note that you’ll need to know 300 words total. This means you’ll be learning 150 new characters to add on to the ones you learned in HSK 1.

Lower Intermediate Level (HSK 3) – 6 to 9 Months

Reaching HSK Level 3 takes approximately six to nine months, and requires you to know 600 words total. So you’ll be learning 300 new characters after you’ve achieved HSK 1 and 2.

Learning 3-4 new characters from the HSK 3 level will let you learn all 300 new words in about three months.

However, remember that you’ll also be introduced to new, more challenging grammar concepts.

Upper Intermediate Level (HSK 4) – About 2 Years

The HSK 4 has 1,200 words total, which means learning an additional 600 words after reaching HSK 3.

The grammar points get more challenging and complex, and you should prioritize getting lots of speaking practice during this level to get comfortable expressing yourself.

Lower Advanced Level (HSK 5) – 3 to 4 Years

HSK 5 is as high as many learners choose to go. You’re usually considered conversationally fluent at this level, knowing around 2,50o characters.

You can expect to reach HSK level 5 after three to four years of consistent studying.

Advanced Level (HSK 6) – About 4+ Years

The last level is HSK 6. This level is full of much more technical vocabulary. In fact, you probably rarely use several of these words in English.

It takes a minimum of four years of consistent study for most learners to reach, and you’ll need to know at least 5,000 characters.

6 Factors that Determine How Long It Will Take You to Learn Chinese

1. Your Time Commitment Each Day

While you don’t necessarily need to spend 10 hours a day for 72 days, if you want to achieve a conversational level without taking a decade, you should at least put in 30 minutes to an hour daily.

Putting in this amount of time is also the most beneficial for long-term memory.

When memorizing large amounts of information over an extended period of time, you risk everything you learned being put into your short-term memory.

In other words, it’s easier and more effective to learn in smaller chunks of content and time.

Whether you have hours a day to spare or not, the biggest takeaway from this factor is that you incorporate Chinese learning, studying and practicing into your daily life.

2. The Quality of Your Learning Resources

Believe it or not, the obstacle in your path to faster fluency could very well be the resources you’re using.

It’s crucial that your primary resources be very high quality.

What does this look like exactly?

Your resources should be:

- Full of practical lessons

- Easy to use

- Fun and exciting

- Challenging

- Diverse in content and practice material

- Modern and relevant

Here’s a roundup of some of the best free Chinese learning resources:

3. How Motivated You Are (and Stay)

The more excited you are to learn, the more you’ll learn, which means the faster you’ll see progress.

It’s easy to be a motivated go-getter in the early stages of learning, but eventually, you might find that your steam has run out. This is especially true if you take on too much in the beginning (like studying for 10 hours a day).

No matter what level you are, every learner has their good and bad days. And no one is immune to becoming unmotivated and falling into a plateau.

But the good news is there are ways to prevent it (and combat it).

My favorite way is to constantly immerse myself in Chinese media.

I love browsing the internet for Chinese YouTube videos, listening to Chinese music while I go for a run and chatting with my language partner (who’s now one of my best friends).

You can also use a resource like FluentU, which teaches you Chinese through authentic videos (like music videos, movie trailers, YouTube videos and more).

You can use learning tools like interactive subtitles and SRS flashcards to practice all of your language skills without getting bored.

4. Previous Language Learning Experience

Let’s face it—if Chinese is the first language you’ve ever tried to learn, it’ll likely be harder for you than someone who has learned a second or third language.

Someone who has experience with language learning will likely know their preferred way of learning, studying and practicing. Plus, already have some favorite resources.

As a beginner, you’re probably wondering:

- How much should I spend on resources?

- What does a good language routine look like?

- How do I even start learning?

It can take a while to get into the swing of things and find out what works best for you. So, don’t worry if you don’t sort all of that out right away! You’re not alone.

But don’t get discouraged if you’re a beginner, and don’t rush the process.

We all want to see progress fast, but rushing it will only demotivate you and cause you to overlook important first steps (like coming up with a language learning roadmap).

5. Your Organization and Chinese Learning Routine

Speaking of routines, let’s dive a little deeper here!

How well you organize and measure your progress—as well as abiding by a consistent routine—will play a critical role in your learning journey.

This can be as simple as keeping flashcards in one place, marking off a checklist or keeping a diary of what you do each day (my personal favorite).

Something important to note is that your learning routine will always be subject to change—and that’s okay!

As you approach new phases of life, reach new levels, face a potential learning plateau and finish resources and courses, your routine will need to adapt.

Rather than bringing yourself to the routine, bring the routine to you.

Besides, the whole point of having a solid language learning routine is to learn in the best and most efficient way possible for you!

6. Whether You Learn Characters or Not

Did you know it’s totally possible to learn Chinese without learning characters?

Not only will it save you some materials, notebooks and possibly a few headaches, but it’ll also save you time.

This is something I did for a long time.

Especially if you’re a beginner, mastering pronunciation, pinyin, vocabulary and grammar should take priority over learning how to write (at least for the moment).

If your goal is to communicate verbally, writing doesn’t need to be a top priority right now.

I’m not dissing characters, though.

They’re fun to learn and are simply part of the language!

But you have to be okay with the time it adds to your routine and pace.

Congratulations!

You’re now fully equipped with the information necessary for answering the question, “How long will it take me to learn Chinese?”

While there’s no magic number, if you consider these factors, I know you can come up with a solid action plan.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)