10 Iconic Chinese Poems (With Translations, Notes and Vocabulary) to Deepen Your Cultural Knowledge

Poems and other forms of literature reveal various perspectives and truths that a typical history textbook may lack.

In addition to being a model for teaching language skills, poetry often contains references to epics, folktales and stories of historical significance.

In this post, I’m going to show you 10 Chinese poems to get you started, along with some background information on each and key terms to help you avoid confusion with the translations.

Contents

- Chinese Poems About Places

- Chinese Poems About Love

- Chinese Poems About Culture

- Chinese Poems About Life

- Tips for Studying Poems on Your Own

- And One More Thing...

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Chinese Poems About Places

1. 登鹳雀楼 (Dēng Guàn Què Lóu) — Climbing Stork Tower

bái rì yī shān jìn,

huáng hé rù hǎi liú;

yù qióng qiān lǐ mù,

gèng shàng yì céng lóu.

The sun sets behind the mountains,

And the Yellow River flows into the sea.

To thoroughly enjoy a thousand-mile sight,

Climb up another level.

About the Poet:

王之渙 (Wang Zhihuan) was a Tang Dynasty poet best known for penning this poem, which was included in the famous poetry anthology 唐诗三百首 (táng shī sān bǎi shǒu) or “Three Hundred Tang Poems.” Stork Tower is three levels tall, located between mountains and the Yellow River in Shanxi province.

Key Terms:

依 (yī) — to go along with

尽 (jìn) — (v.) to end; to use up; (adv.) to the greatest extent

欲 (yù) — (n.) desire; want; (v.) to wish for; to want

穷 (qióng) — (v.) to use up; to exhaust; (adv.) thoroughly; extremely; (adj.) poor; destitute

千里 (qiān lǐ) — a thousand miles; a long distance

2. 终南山 (Zhōng Nán Shān) — The Zhongnan Mountains

太乙近天都,

连山到海隅。

白云回望合,

青霭入看无。

分野中峰变,

阴晴众壑殊。

欲投人处宿,

隔水问樵夫。

tài yǐ jìn tiān dū,

lián shān dào hǎi yú.

bái yún huí wàng hé,

qīng ǎi rù kàn wú.

fēn yě zhōng fēng biàn,

yīn qíng zhòng hè shū.

yù tóu rén chù sù,

gé shuǐ wèn qiáo fū.

The Taiyi Mountains near the Heavenly Capital

Connects to the mountains to the corner of the sea.

Clouds, when I look back, close behind me,

Mists, when I enter them, are gone.

A central peak divides the two sides of the Mountains,

And sunny or cloudy alters in many remarkable gullies.

Needing a place to stay the night,

I ask the woodcutter over the river.

About the Poet:

18th-century influential poet 王维 (Wang Wei) wrote this poem about the Zhongnan mountains. Located south of Xi’an in Shaanxi Province, the Zhongnan mountains are historically known as a dwelling for Taoist hermits, possibly since before the Qin Dynasty. You can also listen to the audio file of this piece to improve your listening skills.

Key Terms:

太乙 (tài yǐ) — Taiyi Mountains, used interchangeably with 终南山 (zhōng nán shān) and 周南山 (zhōu nán shān)

天都 (tiān dū) — Heavenly Capital

隅 (yú) — corner

霭 (ǎi) — mist; haze; cloudy sky

殊 (shū) — (adj.) different; remarkable; (adv.) really; extremely

樵夫 (qiáo fū) — woodman; woodcutter

Chinese Poems About Love

3. 关雎 (Guān Jū) — The Crying Ospreys

guān guān jū jiū,

zài hé zhī zhōu.

yǎo tiǎo shū nǚ,

jūn zǐ hǎo qiú.

“Guan! Guan!” cry the ospreys,

On the islet on the river.

Elegant and graceful is the lady,

A fine match for the gentleman.

About the Poem:

This Chinese poem comes from 诗经 (shī jīng) — The Book of Songs, which dates back to 600 BCE. This one is a famous and beloved poem from Southern Zhou, and also includes Chinese animal sounds for onomatopoeia.

Key Terms:

鸠 (jiū) — (n.) turtledove; (literary) to gather

之 (zhī) — possessive particle equivalent to 的 (de); him; her; it

淑女 (shū nǚ) — lady; wise and virtuous woman

君子 (jūn zǐ) — gentleman; nobleman

逑 (qiú) — mate

4. 相思 (Xiāng Sī) — Lovesickness

hóng dòu shēng nán guó,

qiū lái fā jǐ zhī?

yuàn jūn duō cǎi xié,

cǐ wù zuì xiāng sī.

Red beans grow in the southern lands,

How many branches fall when spring arrives?

May the gentleman gather many of them

This is what makes him the most lovesick.

About the Poem:

王维 (Wang Wei) also penned this poem about one of China’s ancient symbols of love. Red beans (known as adzuki beans in other countries) represent yearning for love and fidelity. The original story tells of a woman waiting for her husband to return from war. She gets sick and dies from thinking about him too much. From her grave grows a red bean tree, pointing in her husband’s direction.

Key Terms:

愿 (yuàn) — to hope; to desire

采 (cǎi) — (n.) collection; (v.) to pick; to extract

撷 (xié) — to collect; to pluck

此 (cǐ) — this; these

相思 (xiāng sī) — (n.) lovesickness; (v.) to yearn; to pine

Chinese Poems About Culture

5. 乡愁 (Xiāng Chóu) — Nostalgia

小时候

乡愁是一枚小小的邮票

我在这头

母亲在那头

长大后

乡愁是一张窄窄的船票

我在这头

新娘在那头

后来啊

乡愁是一方矮矮的坟墓

我在外头

母亲在里头

而现在

乡愁是一湾浅浅的海峡

我在这头

大陆在那头

xiǎo shí hou

xiāng chóu shì yī méi xiǎo xiǎo de yóu piào

wǒ zài zhè tóu

mǔ qīn zài nà tóu

zhǎng dà hòu

xiāng chóu shì yī zhāng zhǎi zhǎi de chuán piào

wǒ zài zhè tóu

xīn niáng zài nà tóu

hòu lái a

xiāng chóu shì yī fāng ǎi ǎi de fén mù

wǒ zài wài tou

mǔ qīn zài lǐ tou

ér xiàn zài

xiāng chóu shì yī wān qiǎn qiǎn de hǎi xiá

wǒ zài zhè tóu

dà lù zài nà tóu

When I was a child,

Nostalgia was a tiny postage stamp.

I, on this side,

My mother, on the other.

When I was older,

Nostalgia became a small ship ticket.

I, on this side,

My bride, on the other.

Later,

Nostalgia was a shallow grave.

I, on the outside,

My mother, on the inside.

And now,

Nostalgia is a gulf, a shallow strait.

I, on this side,

The mainland, on the other.

About the Poet:

余光中 (Yu Guangzhong) passed away in 2017. A contemporary Taiwanese poet, he was best known for this piece “Nostalgia,” which highlighted the displacement and longing for cultural unity between the mainland and the Chinese diaspora.

Key Terms:

乡愁 (xiāng chóu) — homesickness; nostalgia

枚 (méi) — piece; measure word for coins, rings, badges, satellites, etc.

头 (tóu) — side; head; top; beginning; end; measure word for livestock

窄 (zhǎi) — narrow; badly off

方 (fāng) — square; side; place; measure word for square objects

坟墓 (fén mù) — grave; tomb

海峡 (hǎi xiá) — channel; strait

6. 桃夭 (Táo Yāo) — The Peach Tree Tender

桃之夭夭,

灼灼其华。

之子于归,

宜其室家。

桃之夭夭,

有蕡其实。

之子于归,

宜其家室。

桃之夭夭,

其叶蓁蓁。

之子于归,

宜其家人。

táo zhī yāo yāo,

zhuó zhuó qí huá.

zhī zǐ yú guī,

yí qí shì jiā.

táo zhī yāo yāo,

yǒu fén qí shí.

zhī zǐ yú guī,

yí qí jiā shì.

táo zhī yāo yāo,

qí yè zhēn zhēn.

zhī zǐ yú guī,

yí qí jiā rén.

The peach tree budding and tender,

Vivid and bright its flowers.

The maiden to be wed

Is fitting for the house.

The peach tree budding and tender,

Its seedlings abundant indeed.

The maiden to be wed

Is fitting for the home.

The peach tree budding and tender,

Its leaves luxuriant and lush.

The maiden to be wed

Is fitting for the family.

About the Poem:

This poem is also from the 诗经 (shī jīng) collection. In Chinese culture, peach trees and the fruits themselves are symbolic of health, longevity, vitality and (in some cases) immortality.

Key Terms:

桃之夭夭 (táo zhī yāo yāo) — (idiom) the peach trees are in full blossom

灼 (zhuó) — (v.) to burn; to scorch; (adj.) bright; luminous

归 (guī) — to return; to give back to; to be taken care of; to marry

室家 (shì jiā) — house; couple; family; household

蕡 (fén) — (n.) hemp seeds; (adj.) abundant; luxurious

家室 (jiā shì) — wife; family; residence

蓁 (zhēn) — abundant; luxuriant

7. 过故人庄 (Guò Gù Rén Zhuāng) — Visiting an Old Friend’s Farmhouse

故人具鸡黍,

邀我至田家。

绿树村边合,

青山郭外斜。

开轩面场圃,

把酒话桑麻。

待到重阳日,

还来就菊花。

gù rén jù jī shǔ,

yāo wǒ zhì tián jiā.

lǜ shù cūn biān hé,

qīng shān guō wài xiá.

kāi xuān miàn chǎng pǔ,

bǎ jiǔ huà sāng má.

dài dào chóng yáng rì,

hái lái jiù jú huā.

An old friend prepares chicken and millet,

And invites me to his farmhouse.

Green trees surround the entire village,

Green hills stretch beyond the town.

Open the pavilion window facing the courtyard and orchards,

Raise our wine glasses, and speak of hemp and mulberry.

We wait until the day of the Double Ninth Festival,

To return here and admire chrysanthemums.

About the Poem:

Also featured in “Three Hundred Tang Poems,” this piece by 孟浩然 (Meng Haoran) references the Double Ninth Festival, an ancient Chinese holiday with traditions of drinking chrysanthemum tea.

Key Terms:

具 (jù) — (v.) to have; to provide; (n.) tool; device; measure word for devices, coffins and dead bodies

郭 (guō) — outer city wall

轩 (xuān) — pavilion with windows

圃 (pǔ) — garden; orchard

把酒 (bǎ jiǔ) — to raise one’s wine glass

重阳 (chóng yáng) — 9th day of the 9th lunar month; Double Ninth or Yang Festival

Chinese Poems About Life

8. 悯农 (Mǐn Nóng) — Sympathy for the Peasants

chú hé rì dāng wǔ,

hàn dī hé xià tǔ.

shuí zhī pán zhōng cān,

lì lì jiē xīn kǔ.

Cultivating grains at noon,

Sweat dripping into the earth beneath.

Who would have thought the food on your plate,

each and every grain, came from hard work?

About the Poet:

李绅 (Li Shen) was born in 772 AD and lived in the aftermath of the An Lushan Rebellion—the devastating uprising against the Tang Dynasty. The countryside continued to suffer from the damage and unrest, which ended up becoming the central theme of Li’s poems. This one, in particular, was heard across the country.

Key Terms:

锄 (chú) — (n.) hoe; (v.) to hoe; to weed

谁知 (shuí zhī) — who would have thought; unexpectedly; (lit.) who knows

盘中餐 (pán zhōng cān) — food on a plate

粒 (lì) — grain; granule; measure word for small round things

皆 (jiē) — each and every; all

9. 题西林壁 (Tí Xī Lín Bì) — Written on the Wall of the West Woods Temple

横看成岭侧成峰,

远近高低各不同。

不识庐山真面目,

只缘身在此山中。

héng kàn chéng lǐng cè chéng fēng,

yuǎn jìn gāo dī gè bù tóng.

bù shí lú shān zhēn miàn mù,

zhǐ yuán shēn zài cǐ shān zhōng.

A mountain range in panorama becomes a peak from the side,

Far, near, high and low, with no two alike.

I do not know the true face of Lushan Mountain,

Only because I myself am in the mountain.

About the Poet:

苏轼 (Su Shi) was a jack-of-all-trades back in the Song Dynasty. After visiting the mountains, he wrote this poem with the intention of reminding readers to not be blinded by personal prejudices in order to see things as they really are.

Key Terms:

岭 (lǐng) — mountain range

侧 (cè) — (n.) side; (v.) to incline toward; to lean; (adj.) lateral

成 (chéng) — (v.) to become; to complete; (adj.) capable

不识庐山真面目 (bù shí lú shān zhēn miàn mù) — (fig.) can’t see the forest for the trees; (lit.) not to know the true face of Lushan Mountain

缘 (yuán) — cause; reason; karma; fate

10. 枫桥夜泊 (Fēng Qiáo Yè Bó) — Night Mooring at Maple Bridge

月落乌啼霜满天,

江枫渔火对愁眠。

姑苏城外寒山寺,

夜半钟声到客船。

yuè luò wū tí shuāng mǎn tiān,

jiāng fēng yú huǒ duì chóu mián.

gū sū chéng wài hán shān sì,

yè bàn zhōng shēng dào kè chuán.

The moon sets and crows caw as frost fills the atmosphere

Under the riverside maple trees, the fisherman’s light disrupts my sleep.

Outside Gusu City is Hanshan Temple,

At midnight, the sound of bells reaches the ferry.

About the Poet:

张继 (Zhang Ji) was a Tang Dynasty poet who shared his experience of passing through Gusu City (now known as Suzhou City), fighting his homesickness and loneliness by describing the sights and sounds.

Key Terms:

啼 (tí) — to cry; to crow; to hoot

满天 (mǎn tiān) — whole sky

眠 (mián) — to sleep; to hibernate

姑苏城 (gū sū chéng) — Gusu City, now Suzhou ( 苏州 ) City

寒山寺 (hán shān sì) — Hanshan Temple; Cold Mountain Temple

Tips for Studying Poems on Your Own

- Start with the classics. Classic poems (in any language) have been studied and analyzed time and time again, and will always be relevant for learning about history, culture and language. They’re also the most likely to have existing English translations, in case you need references.

- Learn about the poets. Knowing which dynasty or historical period they’re from, their context and any other details can offer additional insight on the poem in question.

- Do a literal translation of every character. Figure out the division of words and phrases (if any). From there, you can determine what definitions work best in the given context. For any unknown characters, try to identify the components before looking it up to improve your reading skills.

Now these Chinese poems weren’t so bad, were they?

Try translating them on your own and compare them with the translations above. By practicing with one Chinese poem at a time, you’ll be training your translation skills for anything!

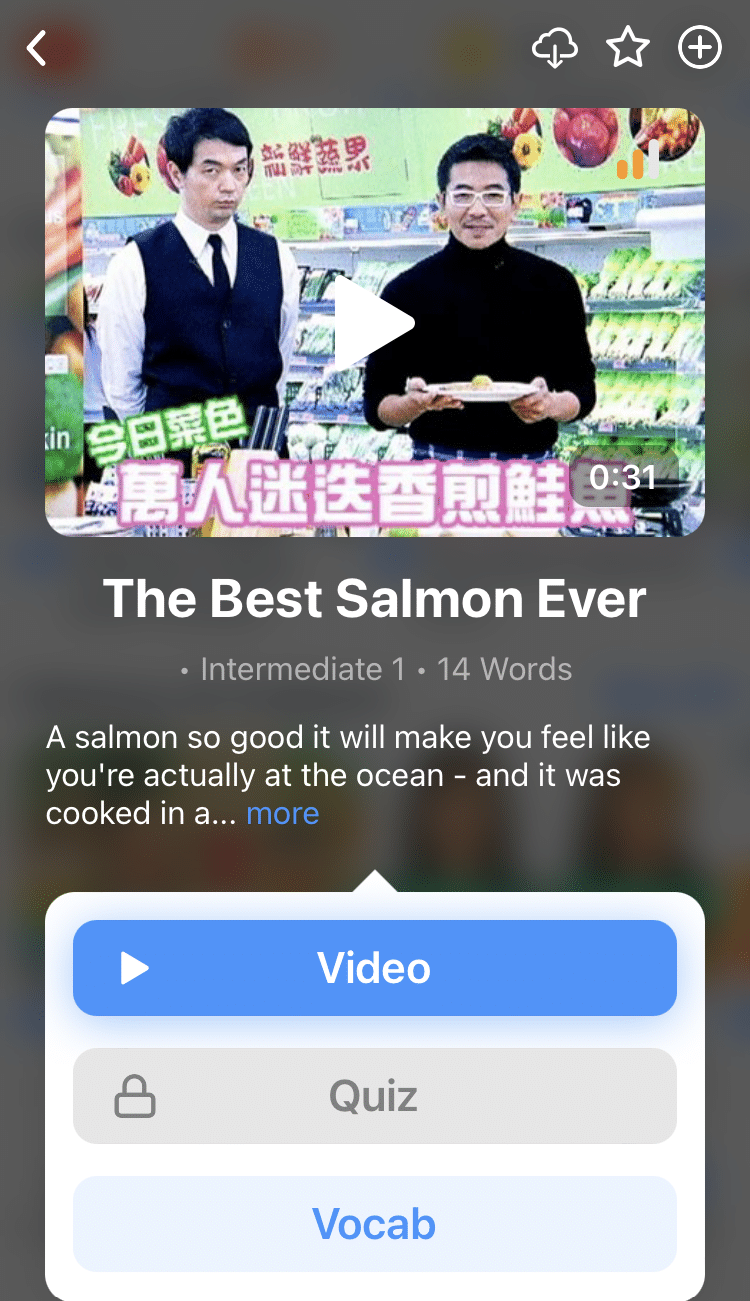

For example, you can see how much of a FluentU video you can understand by just reading the accompanying subtitles, then turn on the English translations or click on any word as the video plays to see what it means.

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

While no two people will share the exact same translation, this language exercise really gives you a new appreciation of Mandarin and its simplicity of characters without compromising the meaning or message of the poems.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing...

If you want to continue learning Chinese with interactive and authentic Chinese content, then you'll love FluentU.

FluentU naturally eases you into learning Chinese language. Native Chinese content comes within reach, and you'll learn Chinese as it's spoken in real life.

FluentU has a wide range of contemporary videos—like dramas, TV shows, commercials and music videos.

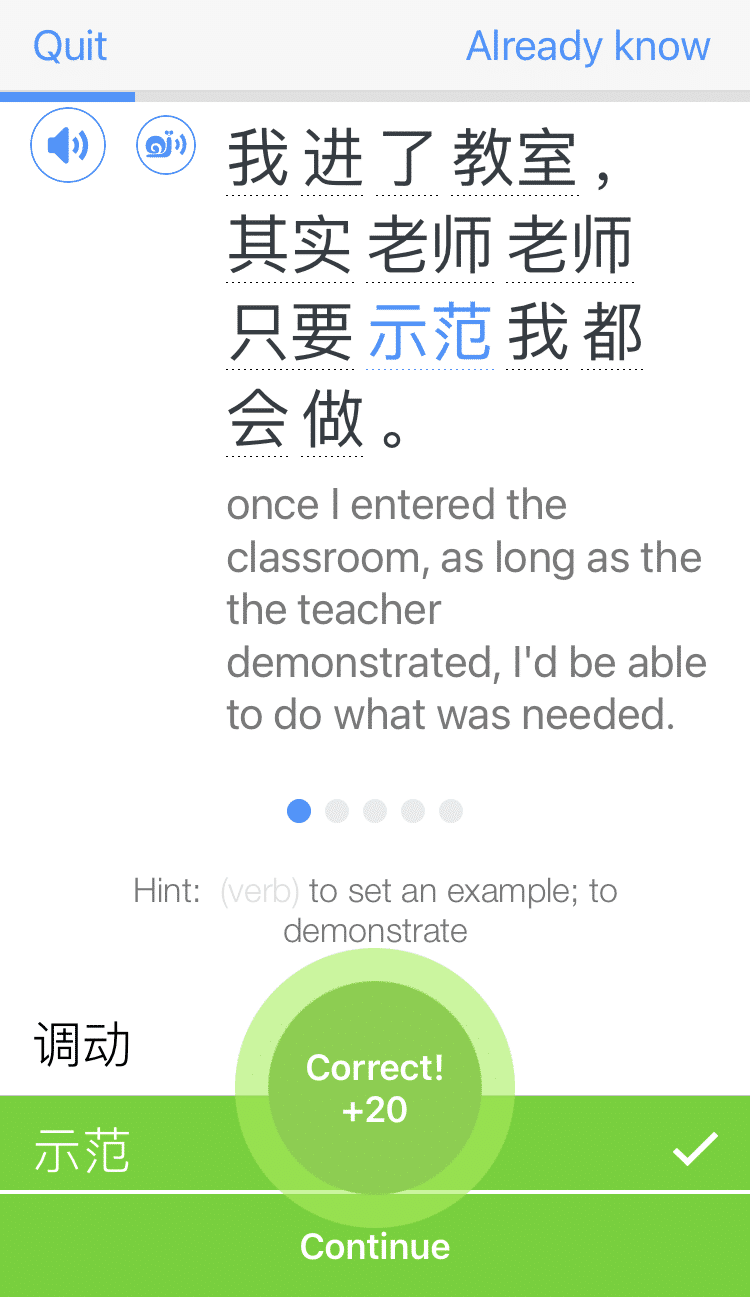

FluentU brings these native Chinese videos within reach via interactive captions. You can tap on any word to instantly look it up. All words have carefully written definitions and examples that will help you understand how a word is used. Tap to add words you'd like to review to a vocab list.

FluentU's Learn Mode turns every video into a language learning lesson. You can always swipe left or right to see more examples for the word you're learning.

The best part is that FluentU always keeps track of your vocabulary. It customizes quizzes to focus on areas that need attention and reminds you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. You have a 100% personalized experience.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)