Chinese “Ba” Sentences: How to Use 把 Correctly, Plus Practice Tips

Once you start pushing toward intermediate Chinese, you’ll discover that there’s more beyond Chinese SVO statements.

The one construction you’ll probably hear the most is the Chinese ba (把) sentence.

In this post, we’ll get you started with the basics: what 把 sentences look like, when and why they’re used, as well as how to get in the habit of using them yourself.

Contents

- What Is a Chinese “Ba” Sentence?

- Use 把 to Emphasize What Happened to an Object

- Use 把 When the Object Has Already Been Defined

- How to Negate 把 Sentences

- How to Use 把 with Two Objects

- How to Ask Questions Using 把

- How to Practice Chinese “Ba” Sentences

- And One More Thing...

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

What Is a Chinese “Ba” Sentence?

In Chinese grammar, the 把 (bǎ) sentence is a construction that focuses on the result or effect of an action.

It has no equivalent in English grammar and completely changes the order of the sentence in Chinese.

When you use 把, you have to remember to put your object before the verb.

Since English speakers just don’t plan their sentences that way, it takes some getting used to.

As a fairly simple example, take the following sentence.

她把饺子吃掉了。

(tā bǎ jiǎo zi chī diào le.)

She ate up the dumplings.

This follows the basic order of a 把 sentence:

Subject (她) + 把 + Object (饺子) + Verb (吃掉了)

There are a lot of sentences in Chinese that sound more natural if you use 把, but you can usually get by without it.

That said, Chinese has at least one common verb where you just can’t use normal English word order: 放 (fàng) meaning “put.”

Here’s an example:

我把书放在桌子上。

(wǒ bǎ shū fàng zài zhuō zi shàng.)

I put the book on the table.

Now that you know what a 把 sentence looks like, we’ll look more carefully at when and why you might want to use it.

把 sentences are often used in situations where you could say, “The subject took the object and did something to it.” (This is, in fact, the likely historical source of the 把 construction.)

Remember our original sentence? You could express roughly the same meaning by saying “She took the dumplings and ate them up.”

Use 把 to Emphasize What Happened to an Object

Unlike SVO statements which answer “What did the subject do?”, 把 sentences answer the following questions:

- “What did the subject do to the object?”

- “What happened to the object?”

And going back to our earlier example, “She ate up the dumplings” works well to answer both questions.

In other words, you should only use 把 when the object has undergone some change or has been strongly affected by the action.

Chinese textbooks and grammar books will sometimes refer to this as “affectedness” or “disposal.”

This is why our example sentence uses 吃掉了 instead of simply 吃了, as 吃掉了 implies a greater effect on the object.

In most 把 sentences:

1. The action is complete. You can see the result of the verb’s action.

2. The effect is complete. The entire object has experienced the effect.

In the case of our dumpling example, the dumplings have undergone a change (from not being eaten to all of them eaten up).

There are certain verbs that lend themselves particularly well to the Chinese 把 construction, such as:

放 (fàng) — put

卖 (mài) — sell

变成 (biàn chéng) — turn into

翻成 (fān chéng) — translate

Here are some sentence examples:

我把我的电脑卖了。

(wǒ bǎ wǒ de diàn nǎo mài le.)

I sold my computer.

他把水变成酒。

(tā bǎ shuǐ biàn chéng jiǔ.)

He turned the water into wine.

Another component of a 把 sentence is that you need to indicate how the verb was carried out, or at least clearly show the action is complete.

Some examples that show completion are the complements 好 (hǎo) and 完 (wán), as in:

我们把作业做好了。

(wǒmen bǎ zuò yè zuò hǎo le.)

We finished the homework.

他把苹果吃完了。

(tā bǎ píng guǒ chī wán le.)

He ate the apple.

Verbs followed by a directional complement also tend to work well with 把 sentences.

One example:

她把桃子摘下来了。

(tā bǎ táo zi zhāi xià lái le.)

She picked the peach.

Notice that the direction won’t always translate into English.

On the other hand, verbs that describe events like thinking, feeling or perceiving, such as 知道 (zhī dào) — know, 喜欢 (xǐ huān) — like, and 看 (kàn) — look, are almost never used with 把 because the object remains unaffected.

It would be strange to say, “She took the dumplings and liked them.”

Use 把 When the Object Has Already Been Defined

Because of the special meaning of a 把 sentence, only certain kinds of objects can be used in them.

In most 把 sentences, both the speaker and the listener know the object being talked about.

This is another way of saying that the object needs to be “definite.” Think about whether you could use the word “the” with the object. If you can’t, 把 isn’t going to work.

Suppose you wanted to tell your coworker what you ate for lunch, for example.

In this situation, you can tell your coworker:

我吃饺子了。

(wǒ chī le jiǎo zi.)

I ate dumplings.

But if your coworkers already know which dumplings you’re referring to (i.e. you already had a prior discussion about the soup dumplings you made last night and brought to work), then you can say:

我把饺子吃了。

(wǒ bǎ jiǎo zi chī le.)

I ate the dumplings.

How to Negate 把 Sentences

The most important note for negating these sentences is that the negation must come before 把.

This is because, again, the purpose of 把 sentences is to explain what happened to an object. Putting the negation word after 把 would mean that nothing happened to the object—it just doesn’t work.

To form the negative of a 把 construction, you’ll often see 没有 (méi yǒu) or its shortened form 没, which are used to negate something that happened in the past:

我没有把书还给他。

(wǒ méi yǒu bǎ shū huán gěi tā.)

I didn’t give the book back to him.

你没把你的房间打扫干净。

(nǐ méi bǎ nǐ de fáng jiān dǎ sǎo gān jìng.)

You didn’t clean your room.

For present and future timeframes, you can use either 不要 (bù yào) or 别 (bié) to negate the sentence in the manner of a command:

不要把钱借给他。

(bù yào bǎ qián jiè gěi tā.)

Don’t lend him money.

你别把我的房间弄乱了!

(nǐ bié bǎ wǒ de fáng jiān nòng luàn le!)

Don’t you mess up my room!

How to Use 把 with Two Objects

It is possible, depending on your verb, that a 把 sentence will have both a direct object and an indirect object (the latter of which is typically introduced by 给 (gěi) — to, for.

Common verbs that have two objects include:

卖 (mài) — sell

送 (sòng) — deliver/give

拿 (ná) — take

递 (dì) — hand over

借 (jiè) — borrow/lend

还 (huán) — give back/return

介绍 (jiè shào) — introduce

Take this sentence as an example:

她把房子卖给新婚夫妇了。

(tā bǎ fáng zi mài gěi xīn hūn fū fù le.)

She sold the house to the newlyweds.

That example follows the formula for using 把 with two objects:

Subject (她) + 把 + Direct Object (房子) + Verb (卖) + 给 + Indirect Object (新婚夫妇)

More examples, with the two objects in bold:

他把那个礼物送给了他的女朋友。

(tā bǎ nà ge lǐ wù sòng gěi le tā de nǚ péng yǒu.)

He gave that gift to his girlfriend.

我要把你介绍给汉语老师。

(wǒ yào bǎ nǐ jiè shào gěi hàn yǔ lǎo shī.)

I’m going to introduce you to the Chinese teacher.

How to Ask Questions Using 把

You can use any of the three typical Chinese question formations with 把.

First, you can use a question particle, like this:

你把作业写了吗?

(nǐ bǎ zuò yè xiě le ma?)

Have you done your homework?

You can also use a question word (like “who” or “when”):

她把我的手机放在哪里了?

(tā bǎ wǒ de shǒu jī fàng zài nǎ lǐ le?)

Where did she put my phone?

Or you can use the positive and negative verb form, as in 有没有 (yǒu méi yǒu) or 要不要 (yào bù yào), and place it in front of 把:

你要不要把饺子吃完?

(nǐ yào bú yào bǎ jiǎo zi chī wán?)

Are you going to finish the dumplings?

Notice that in each of these questions, the basic 把 structure is unaffected and does not affect the question structure either. Simply put the question particle, word or words where they would normally go in the sentence.

How to Practice Chinese “Ba” Sentences

Here are some practical ideas you can try to start using 把 sentences in your conversations:

Walk yourself through your daily routine

As you get ready in the morning, there are all sorts of things you do to objects.

Try talking your way through your routine in Chinese. And if you don’t live alone, consider keeping the conversation in your head!

我把脸洗干净了。

(wǒ bǎ liǎn xǐ gān jìng.)

I washed my face clean.

我把鸡蛋煎好了。

(wǒ bǎ jī dàn jiān hǎo le.)

I finished frying the eggs.

我把钥匙放在口袋里。

(wǒ bǎ yào shi fàng zài kǒu dài lǐ.)

I put my keys in my pocket.

Practice with a language partner

把 sentences also work nicely with imperatives or commands.

It follows the same basic formula as above, just without a subject.

把 + Object + Verb

Have your language partner boss you around for a while, while you get up and carry out the actions.

把灯打开。

(bǎ dēng dǎ kāi.)

Turn on the light.

把笔放在椅子上。

(bǎ bǐ fàng zài yǐ zi shàng.)

Put your pen on the chair.

把碗擦好。

(bǎ wǎn cā hǎo.)

Wipe the dishes clean.

Tell a story—with feeling!

Chinese speakers don’t just use 把 sentences at random—they have a reason.

And one of those reasons is to make a conversation sound more dramatic.

There’s a whole book about this by Zhuo Jing-Schmidt, actually, should you be looking for a (long) diversion from your studies.

So think of something exciting that happened recently! And then think about how you could tell a simple version in Chinese with a 把 sentence:

昨天我去商城。有人碰了我一下。

(zuó tiān wǒ qù shāng chéng. yǒu rén pèng le wǒ yī xià.)

I was going into the mall yesterday. Someone bumped into me.

我转眼看。小偷把我的钱包偷走了!

(wǒ zhuǎn yǎn kàn. xiǎo tōu bǎ wǒ de qián bāo tōu zǒu le!)

I turned and looked. A thief had stolen my purse!

You made it! And if you need some more help learning this useful vocabulary word, you can find it on the immersive learning platform, FluentU.

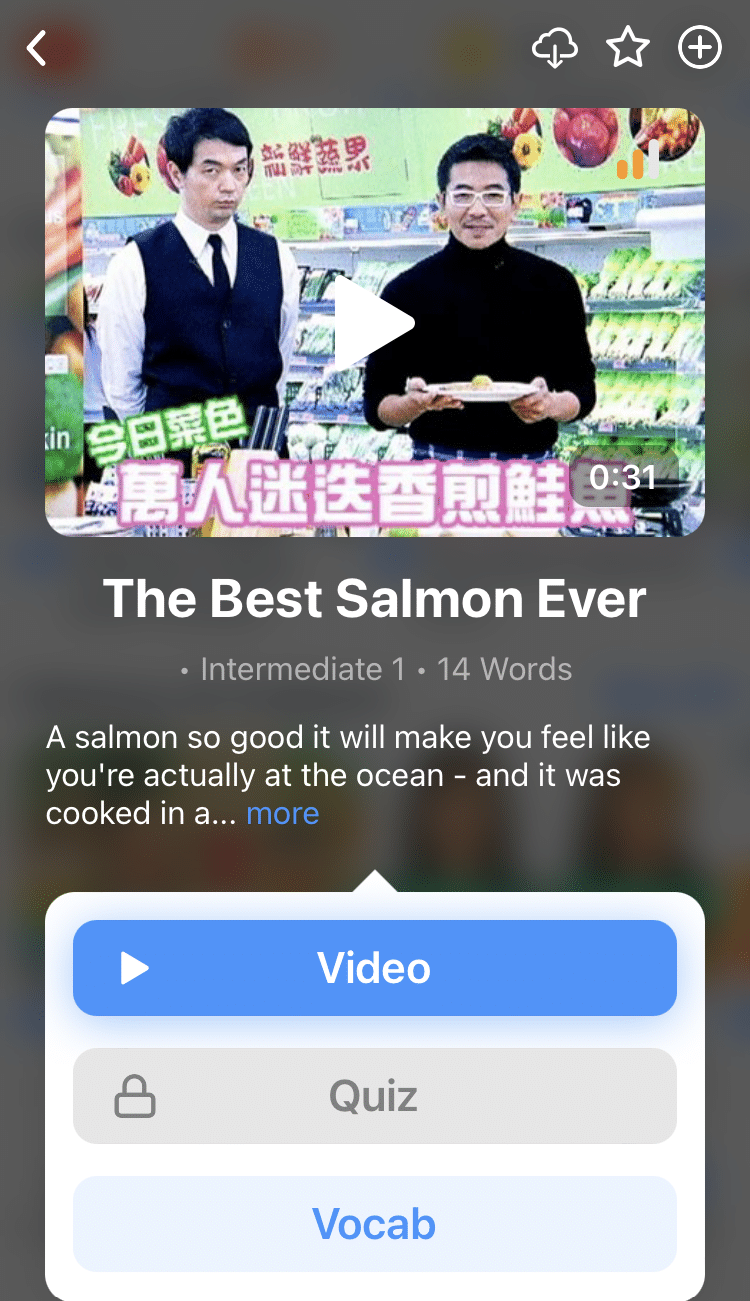

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Hopefully, you now have a better understanding of the Chinese 把 construction so you can speak Mandarin more fluently.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing...

If you want to continue learning Chinese with interactive and authentic Chinese content, then you'll love FluentU.

FluentU naturally eases you into learning Chinese language. Native Chinese content comes within reach, and you'll learn Chinese as it's spoken in real life.

FluentU has a wide range of contemporary videos—like dramas, TV shows, commercials and music videos.

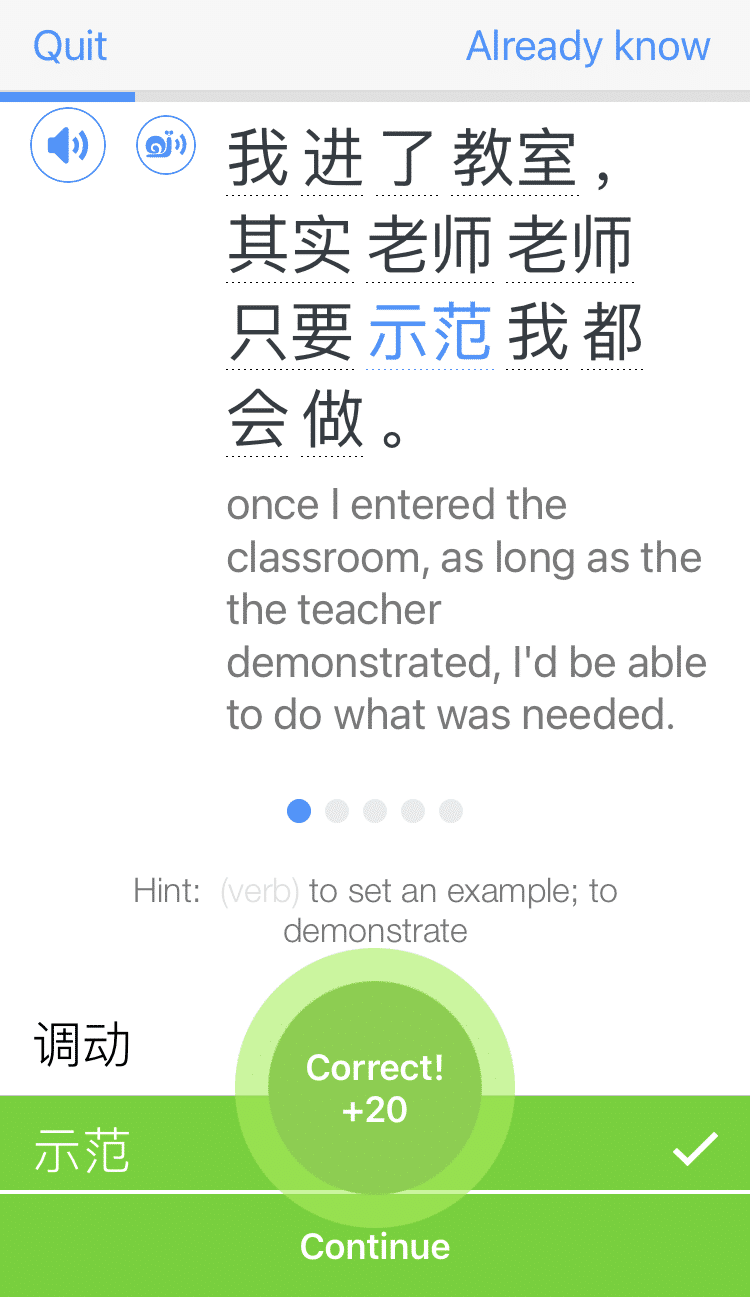

FluentU brings these native Chinese videos within reach via interactive captions. You can tap on any word to instantly look it up. All words have carefully written definitions and examples that will help you understand how a word is used. Tap to add words you'd like to review to a vocab list.

FluentU's Learn Mode turns every video into a language learning lesson. You can always swipe left or right to see more examples for the word you're learning.

The best part is that FluentU always keeps track of your vocabulary. It customizes quizzes to focus on areas that need attention and reminds you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. You have a 100% personalized experience.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)