88 Business Chinese Vocabulary Terms (Including Audio and Examples)

Knowing Mandarin Chinese opens new doors of opportunity and increases your hireability to employers. But this requires a lot of industry-specific vocabulary that’ll soon have you knee-deep in words pertaining to titles, industry jargon and positions within a company.

Here are 88 of the most important business Chinese vocabulary plus useful information about Chinese business culture.

Contents

- Key Business Chinese Vocabulary

- How to Discuss a Contract and Raise Objections in Chinese

- How to Elegantly Apologize in Chinese

- Exchanging Traditions with Chinese Business Connections

- How to Make a Toast in Chinese Business Culture

- How to Bid Farewell in Chinese

- Why Should I Learn Business Chinese?

- And One More Thing...

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Key Business Chinese Vocabulary

Vocabulary for Going to Work

1. 工作 (gōng zuò) — Work

我最近找到新工作了。(wǒ zuì jìn zhǎo dào xīn gōng zuò le)

I just got a new job (work).

2. 上班 (shàng bān) — Start work

我每天九点上班。(wǒ měi tiān jiǔ diǎn shàng bān)

I start work every day at 9 AM.

3. 下班 (xià bān) — Finish work

我通常五点下班。(wǒ tōng cháng wǔ diǎn xià bān)

Usually I get off at 5 PM.

4. 加班 (jiā bān) — Work overtime

公司忙的时候,我必须加班。(gōng sī máng de shí hòu, wǒ bì xū jiā bān)

During the busy season, I need to work overtime.

5. 办公室 (bàn gōng shì) — Office

我们的办公室在市中心的一座大楼里。(wǒ mén de bàn gōng shì zài shì zhōng xīn de yí zuò dà lóu lǐ)

Our office is in a tall building downtown.

6. 工厂 (gōng chǎng) — Factory

我们还有几家工厂在深圳。(wǒ mén hai yǒu jǐ jiā gōng chǎng zài shēn zhèn)

We also have several factories in Shenzhen.

7. 出差 (chū chāi) — Business trip

年底的时候,我会到北京出差。 (nián dǐ de shí hòu, wǒ huì dào běi jīng chū chāi)

At the end of the year, I will go on a business trip to Beijing.

8. 职业 (zhí yè) — Occupation

我的职业是医生。(wǒ de zhí yè shì yī shēng)

My occupation is a doctor.

9. 薪水 (xīn shuǐ) — Salary

我的薪水每个月都会涨。 (wǒ de xīn shuǐ měi gè yuè dōu huì zhǎng)

My salary increases every month.

10. 工作日 (gōng zuò rì) — Workday

工作日我通常很忙。 (gōng zuò rì wǒ tōng cháng hěn máng)

I’m usually busy on workdays.

Phrases for Arriving on a Business Trip

11. 路上辛苦吗? (lù shàng xīn kǔ ma?) — Did you have a hard journey?

有一点。 (yǒu yì diǎn) — Yes, a little.

不辛苦,没事。 (bù xīn kǔ, méi shì) — No, not hard, it was nothing.

12. 幸会幸会。 (xìng huì xìng huì.) — Pleasure to meet you!

13. 久仰大名。 (jiǔ yǎng dà míng.) — I’ve heard a lot about you!

How to Talk About People at Work

14. 老板 (lǎo bǎn) — Boss

黄先生是我们的老板。(huáng xiān sheng shì wǒ mén de lǎo bǎn)

Mr. Huang is our boss.

15. 总经理 (zǒng jīng lǐ) — CEO

黄先生也是总经理。(huáng xiān shēng yě shì zǒng jīng lǐ)

Mr. Huang is also the CEO.

16. 经理 (jīng lǐ) — Manager

王经理有很多年的工作经验。(wáng jīng lǐ yǒu hěn duō nián de gōng zuò jīng yàn)

Mr. Wong, our manager, has many years of work experience.

17. 员工 (yuán gōng) — Employee

我们公司有四百多个员工。(wǒ mén gōng sī yǒu sì bǎi duō gè yuán gōng。)

Our company has over 400 employees.

18. 客户 (kè hù) — Client

我们大部分的客户都是外国人。(wǒ mén dà bù fēn de kè hù doū shì wài guó rén)

Our clients are mainly foreigners.

19. 雇主 (gù zhǔ) — Employer

我的雇主很慷慨,给我加了薪。 (wǒ de gù zhǔ hěn kāng gài, gěi wǒ jiā le xīn)

My employer is generous; they gave me a raise.

20. 同事 (tóng shì) — Colleague

我的同事们都很友好。 (wǒ de tóng shì men dōu hěn yǒu hǎo)

My colleagues are all very friendly.

21. 领导 (lǐng dǎo) — Leader

她是我们团队的领导。 (tā shì wǒmen tuán duì de lǐng dǎo)

She is the leader of our team.

22. 顾客 (gù kè) — Customer

我们的顾客总是第一位的。 (wǒ men de gù kè zǒng shì dì yī wèi de)

Our customers always come first.

23. 团队 (tuán duì) — Team

我们的团队在一起已经很长时间了。 (wǒ men de tuán duì zài yì qǐ yǐ jīng hěn cháng shí jiān le)

Our team has been together for a long time.

24. 财务分析师 (cái wù fēn xī shī) — Financial Analyst

财务分析师帮助公司做出财务决策。 (cái wù fēn xī shī bāng zhù gōng sī zuò chū cái wù jué cè)

Financial analysts help the company make financial decisions.

25. 企业顾问 (qǐ yè gù wèn) — Business Consultant

这位企业顾问为我们提供战略建议。 (zhè wèi qǐ yè gù wèn wèi wǒ men tí gōng zhàn lüè jiàn yì)

This business consultant provides us with strategic advice.

26. 人力资源经理 (rén lì zī yuán jīng lǐ) — Human Resources Manager

人力资源经理负责招聘和员工培训。 (rén lì zī yuán jīng lǐ fù zé zhāo pìn hé yuán gōng péi xùn)

The human resources manager is responsible for recruitment and employee training.

Workplace Tools and Equipment

27. 电脑 (diàn nǎo) — Computer

到了办公司以后,我会先打开电脑。(dào le bàn gōng sī yǐ hòu, wǒ huì xiān dǎ kāi diàn nǎo)

When I get to work, the first thing I do is turn on the computer.

28. 电邮 (diàn yóu) — Email

我每天都会收到许多的电邮。(wǒ měi tiān doū huì shōu dào xǔ duō de diàn yóu)

Every day, I receive many emails.

29. 名片 (míng piàn) — Business card

我们交换名片吧。(wǒ mén jiāo huàn míng piàn bā)

Let’s exchange business cards.

30. 文件 (wén jiàn) — Document

你有收到我寄给你的文件吗?(nǐ yǒu shōu dào wǒ jì gěi nǐ de wén jiàn má?)

Did you get the document I sent you?

31. 打印机 (dǎ yìn jī) — Printer

打印机没有纸了。(dǎ yìn jī méi yǒu zhǐ le。)

The printer is out of paper.

32. 复印机 (fù yìn jī) — Photocopier

你会不会用复印机?(nǐ huì bu huì yòng fù yìn jī?)

Do you know how to use the photocopier?

33. 电话 (diàn huà) — Telephone

我需要给客户打个电话。 (wǒ xū yào gěi kè hù dǎ gè diàn huà)

I need to make a phone call to the client.

34. 文件夹 (wén jiàn jiā) — File Folder

把这些文件整理到文件夹里。 (bǎ zhè xiē wén jiàn zhěng lǐ dào wén jiàn jiā lǐ)

Organize these documents into the file folder.

35. 桌子 (zhuō zi) — Desk

我的桌子上有很多文件。 (wǒ de zhuō zi shàng yǒu hěn duō wén jiàn)

There are many documents on my desk.

36. 椅子 (yǐ zi) — Chair

这把椅子很舒适。 (zhè bǎ yǐ zi hěn shū shì)

This chair is very comfortable.

37. 电话会议设备 (diàn huà huì yì shè bèi) — Conference Call Equipment

我们需要准备好电话会议设备。 (wǒ men xū yào zhǔn bèi hǎo diàn huà huì yì shè bèi)

We need to prepare the conference call equipment.

38. 钢笔 (gāng bǐ) — Pen

我的钢笔用完了,你有多余的吗? (wǒ de gāng bǐ yòng wán le, nǐ yǒu duō yú de ma?)

I ran out of pens. Do you have any extras?

39. 书架 (shū jià) — Bookshelf

我把这本书放在书架上了。 (wǒ bǎ zhè běn shū fàng zài shū jià shàng le)

I placed this book on the bookshelf.

40. 计算器 (jì suàn qì) — Calculator

我的计算器需要更换电池。 (wǒ de jì suàn qì xū yào gēng huàn diàn chí)

My calculator needs a battery replacement.

41. 文件柜 (wén jiàn guì) — File Cabinet

这份合同存档在文件柜里。 (zhè fèn hé tong cún dàng zài wén jiàn guì lǐ)

This contract is stored in the file cabinet.

42. 白板 (bái bǎn) — Whiteboard

我们会在白板上记录讨论的内容。 (wǒ men huì zài bái bǎn shàng jì lù tǎo lùn de nè iróng)

We will record the discussion on the whiteboard.

43. 扫描仪 (sǎo miáo yí) — Scanner

请使用扫描仪扫描这份文件。 (qǐng shǐ yòng sǎo miáo yí sǎo miáo zhè fèn wén jiàn)

Please use the scanner to scan this document.

44. 相机 (xiàng jī) — Camera

我们需要一台相机拍摄产品照片。 (wǒ men xū yào yì tái xiàng jī pāi shè chǎn pǐn zhào piàn)

We need a camera to take product photos.

Commonly-used Business Words

45. 会议 (huì yì) — Meeting

我下午两点跟吴小姐有个会议。(wǒ xià wǔ liǎng diǎn gēn wú xiǎo jiě yǒu ge huì yì)

I have a meeting at 2 PM with Ms. Wu.

46. 谈生意 (tán shēng yì) — Discuss business

我们在餐厅里谈生意。(wǒ mén zài cān tīng lǐ tán shēng yì)

We discussed business in a restaurant.

47. 成交交易 (chéng jiāo jiāo yì) — Make a deal

我们终于成交了。(wǒ mén zhōng yú chéng jiāo le)

We finally closed the business deal.

48. 处理问题 (chǔ lǐ wèn tí) — Manage problems

我必须跟我的同事们处里一些问题。(wǒ bì xū gēn wǒ de tóng shì mén chǔ lǐ yì xiē wèn tí)

My coworkers and I need to manage some problems.

49. 合同 (hé tong) — Contract

我们需要签订一份合同。 (wǒ men xū yào qiān dìng yí fèn hé tong)

We need to sign a contract.

50. 谈判 (tán pàn) — Negotiation

谈判还在进行中。 (tán pàn hái zài jìn xíng zhōng)

Negotiations are still ongoing.

51. 市场 (shì chǎng) — Market

我们正在研究市场趋势。 (wǒ men zhèng zài yán jiū shì chǎng qū shì)

We are researching market trends.

52. 投资 (tóu zī) — Investment

这个项目需要大量的投资。 (zhè ge xiàng mù xū yào dà liàng de tóu zī)

This project requires a significant investment.

53. 贸易 (mào yì) — Trade

贸易战会影响全球经济。 (mào yì zhàn huì yǐng xiǎng quán qiú jīng jì)

Trade wars can affect the global economy.

54. 期限 (qī xiàn) — Deadline

请注意这个项目的 期限,请在星期五之前完成这个项目。(qǐng zài xīng qí wǔ zhī qián wán chéng zhè ge xiàng mù, qǐng zhù yì zhè ge xiàng mù dì qī xiàn).

Please note the deadline for this project. Please complete this project by Friday.

55. 工资 (gōng zī) — Wages

我的 工资 是每月 15,000 元。(wǒ de gōng zī shì měi yuè shí wàn wǔ qiān yuán.)

My salary is 15,000 yuan per month.

56. 材料 (cái liào) — Material

我们需要 收集 更多 关于 这个 项目的 材料。(wǒ men xū yào shōu jí gèng duō guān yú zhè ge xiàng mù de cái liào.)

We need to gather more materials about this project.

57. 价格 (jià gé) — Price

我们需要 协商 这个 产品的 价格。(wǒ men xū yào xié shāng zhè ge chǎn pǐn de jià gé.)

We need to negotiate the price of this product.

58. 交货 (jiāo huò) — Delivery

供应商 承诺 在 下个月 15日 之前 交货。(gōng yìng shāng chéng nuò zài xià gè yuè 15 rì zhī qián jiāo huò.)

The supplier promises to deliver the goods before the 15th of next month.

59. 付款 (fù kuǎn) — Payment

请 查收 附件 中的 付款 方式。(qǐng chá shōu fu jiàn zhōng de fù kuǎn fāng shì.)

Please review the payment methods in the attachment.

60. 生产力 / 生产率 (shēng chǎn lì / shēng chǎn lǜ) — Productivity

我们需要 提高 员工 的 生产力。(wǒ men xū yào tí gāo yuán gōng de shēng chǎn lì.)

We need to improve the productivity of our employees.

61. 年增长率 (nián zēng zhǎng lǜ) — Annual growth rate

公司 去年的 年增长率 为 20%。(gōng sī qù nián de nián zēng zhǎng lǜ wéi 20%.)

The company’s annual growth rate last year was 20%.

62. 国民生产总值 (guó mín shēng chǎn zǒng zhí) — GDP (Gross Domestic Product)

中国 的 国民生产总值 在 过去 十年 里 增长了 100%。(zhōng guó de guó mín shēng chǎn zǒng zhí zài guò qù shí nián lǐ zēng zhǎng le 100%.)

China’s GDP has grown by 100% over the past decade.

63. 市场份额 (shì chǎng fèn é) — Market share

公司 的目标 是 在 三年 内 将 市场份额 提高 到 30%。(gōng sī de mù biāo shì zài sān nián nèi jiāng shì chǎng fèn è tí gāo dào 30%.)

The company’s goal is to increase its market share to 30% within three years.

64. 业务模式 (yè wù mó shì) — Business model

公司 一直在 探索 新的 业务模式。(gōng sī yī zhí zài tàn suǒ xīn de yè wù mó shì)

The company has been exploring new business models

65. 网店 (wǎng diàn) — E-store

公司 最近 开设 了 一家 网店 以 扩大 其 市场 份额。(gōng sī zuì jìn kāi shè le yī jiā wǎng diàn yǐ kuò dà qí shì chǎng fèn è.)

The company recently opened an online store to expand its market share.

66. 实体店 (shí tǐ diàn) — Physical store

公司 计划 在 明年 开设 几家 实体店 以 补充 其 网店 业务。(gōng sī jì huà zài míng nián kāi shè jǐ jiā shí tǐ diàn yǐ bù chōng qí wǎng diàn yè wù.)

The company plans to open several physical stores next year to complement its online store business.

67. 全球性企业 (quán qiú xìng qǐ yè) — Global company

公司 已经 发展 成为 一家 全球性企业。(gōng sī yǐ jīng fā zhǎn chéng wéi yī jiā quán qiú xìng qǐ yè.)

The company has developed into a global enterprise.

68. 能力 / 性能 (néng lì / xìng néng) — Capabilities

员工 需要 不断 提高 其 工作 能力。(yuán gōng xū yào bù duàn tí gāo qí gōng zuò néng lì.)

Employees need to continuously improve their work skills.

69. 全局的 (quán jú de) — Global / Big-picture

领导 需要 具有 全局的 眼光 和 思维。(lǐng dǎo xū yào jù yǒu quán jū de yǎn guāng hé sī wéi.)

Leaders need to have a big-picture perspective and thinking.

70. 局部的 (jú bù de) — Regional

公司 正在 制定 针对 不同 局部 市场 的 营销 策略。(gōng sī zhèng zài zhì dìng zhēng duì bù tóng jú bù shì chǎng de yíng xiāo cé lǜ.)

The company is developing marketing strategies targeted towards different regional markets.

71. 当地 (的) (dāng dì [de]) — Local

公司 注重 与 当地 企业 合作。(gōng sī zhòng zhù yǔ dāng dì qǐ yè hé zuò.)

The company emphasizes cooperation with local businesses.

72. 境外游 (jìng wài yóu) — Overseas travel

公司 今年 计划 组织 员工 去 境外游。(gōng sī jīn nián jì huà zǔ zhī yú gōng qù jìng wài yóu.)

The company plans to organize a trip abroad for its employees this year.

73. 基础设施 (jī chǔ shè shī) — Infrastructure

良好的 基础设施 是 经济 发展 的 重要 条件。(liáng hǎo de jī chǔ shè shī shì jīng jì fā zhǎn de zhòng yào tiáo jiàn.)

Good infrastructure is an important condition for economic development.

74. 市值 (shì zhí) — Market value (the price at which something will be traded)

这家科技公司 的 市值 已经 超过 1000亿 美元。(zhè jiā kē jì gōng sī de shì zhí yǐ jīng chāo guò 1000 yì měi yuán.)

This technology company’s market value has already surpassed 100 billion US dollars.

75. 模范 (mó fàn) — Model

这位 员工 是 公司 的 模范,他 工作 认真 负责,同事 都 以 他 为 榜样。(zhè wèi yú gōng shì gōng sī de mó fàn, tā gōng zuò rén zhēn fù zé, tóng shì dōu yǐ tā wéi bǎng yàng.)

This employee is a model for the company. He is dedicated to his work, and his colleagues all look up to him.

76. 城市化 (chéng shì huà) — Urbanization

城市化 对 经济 发展 具有 重要 影响。(chéng shì huà duì jīng jì fā zhǎn jù yǒu zhòng yào yǐng xiǎng.)

Urbanization has a significant impact on economic development.

77. 私营企业 (sī yíng qǐ yè) — Private sector

为了促进经济发展,政府鼓励私营企业创新。(wèi le cù jìn jīng jì fā zhǎn, zhèng fǔ gǔ lì sī yíng qǐ yè chuàng xīn.)

In order to promote economic development, the government encourages innovation in the private sector.

78. 公共部门 (gōng gòng bù mén) — Public sector

公共部门 在 社会 治理 中 发挥 着 重要 作用。(gōng gòng bù mén zài shè huì zhì lǐ zhōng fā huī zhe zhòng yào zuò yòng.)

The public sector plays an important role in social governance.

79. 一线城市 / 二线城市 (yī xiàn chéng shì / èr xiàn chéng shì) — Tier 1/Tier 2 cities

二线城市 拥有 巨大 的 发展潜力。(èr xiàn chéng shì yǒu yǒng jù dà de fā zhǎn qián lǐ.)

Second-tier cities have great development potential.

Departments Within a Company

80. 会计 (kuài jì) — Accounting

我们的会计部门很严格。(wǒ mén de kuài jì bù mén hěn yán gé)

Our accounting department is very strict.

81. 人事处 (rén shì chù) — Human Resources

我以前在人事处工作。(wǒ yǐ qián zài rén shì chù gōng zuò)

I used to work in Human Resources.

82. 信息管理 (xìn xī guǎn lǐ) — Information Technology

我们的信息管理部门很有效率。(wǒ mén de xìn xī guǎn lǐ bù mén hěn yǒu xiào lǜ)

Our IT department is very efficient.

83. 营销 (yíng xiāo) — Marketing

营销部门需要我们的货品照片。(yíng xiāo bù mén xū yào wǒ mén de huò pǐn zhào piàn)

The marketing department needs our product photos.

84. 财务 (cái wù) — Finance

财务负责管理公司的财务。 (cái wù fù zé guǎn lǐ gōng sī de cái wù)

Finance is responsible for managing the company’s finances.

85. 销售 (xiāo shòu) — Sales

销售的任务是推动产品销售。 (xiāo shòu de rèn wù shì tuī dòng chǎn pǐn xiāo shòu)

Sales’ task is to drive product sales.

86. 生产 (shēng chǎn) — Production

生产部门负责制造产品。 (shēng chǎn bù mén fù zé zhì zào chǎn pǐn)

The production department is responsible for manufacturing products.

87. 市场研究 (shì chǎng yán jiū) — Market Research

市场研究部负责分析市场数据。 (shì chǎng yán jiū bù fù zé fēn xī shì chǎng shù jù)

The market research department is responsible for analyzing market data.

88. 管理 (guǎn lǐ) — Management

管理岗的人负责协调公司的各个部门。 (guǎn lǐ gāng de ren fù ze xié tiáo gōng sī de gè ge bù mén)

People in the management positions are responsible for coordinating various departments of the company.

Now that you’ve mastered these 88 basic business Chinese vocabulary, you should be better equipped to do business in Chinese.

But there’s still much more to learn, so I encourage you to keep on getting out there and broadening your horizons. You can use FluentU’s language learning platform, for example, to get more examples of Chinese phrases used in native settings through video clips.

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

How to Discuss a Contract and Raise Objections in Chinese

I’m not qualified to cover any aspects of the legal writing of a contract, but there are a few useful Mandarin Chinese grammar structures that’ll serve you well if you need to raise objections or zero in on a particular point at any stage of the conversation.

Like other Asian cultures, China favors a less direct and confrontational approach to raising objections than places like the U.S.

As you’ve learned above, helping your counterpart to 保住面子 (bǎo zhù miàn zi) — save face is essential if you want to succeed in the long term.

Let’s explore this in detail with an example concerning a 合同.

Your Chinese counterpart asks you if you’ve seen the contract and if you have any questions:

合同你看过了吗?有没有问题? (hé tóng nǐ kàn guò le ma? yǒu méi yǒu wèn tí?) — Have you read the contract? Are there any problems?

You have a problem with the 价格. You could state, “I have a problem with the price,” but this direct approach could be interpreted as confrontational.

Instead, formulate your sentence to emphasize that everything apart from the price is okay.

除了价格以外,其他的都没问题。 (chú le jià gé yǐ wài, qí tā de dōu méi wèn tí.) — Apart from the price, everything else is fine.

As we learned above, you can substitute the keyword “price” with any other appropriate term to politely draw attention to the aspect that you want to discuss. For example:

除了期限以外,其他的都没问题。 (chú le qī xiàn yǐ wài, qí tā de dōu méi wèn tí.) — Apart from the deadline, everything else is fine.

How to Elegantly Apologize in Chinese

As a visitor in a foreign land, you’re not expected to be perfect. You’re clearly going the extra mile, and making an effort in Chinese will be noted and appreciated.

If you accidentally or unthinkingly cause someone to 丢脸 (diū liǎn) — lose face, or trip up in another way, a simple apology can go a long way toward getting you back on firm ground.

There are many ways to apologize in Chinese and their English translations can seem quite drastic. The most common three are:

- 对不起 (duì bù qǐ). This is the closest English equivalent to “I’m sorry” that’s useful in most situations. It literally means “I cannot face you.”

- 不好意思 (bù hǎo yì si). This apology phrase is used to express embarrassment—if you mistake someone’s name or make a language faux pas, then 不好意思 is probably the safest bet.

- 抱歉 (bào qiàn). This is the most formal option for an apology, which is typically used in written Chinese. 抱歉 is a more heavy-duty expression than 对不起 or 不好意思. Unlike the other two, it’s not something you’d use if you bumped into someone in the subway or spilled your drink.

Lastly, if you’re on the receiving end of an apology, you can politely brush it aside with 没关系 (méi guān xì).

Exchanging Traditions with Chinese Business Connections

Business Card Etiquette

In China, someone’s business card (名片 — míng piàn) is a reflection of him or herself. So how you treat their business card represents how you think of them. It formalizes and acknowledges 第一次见面 (dì yī cì jiàn miàn) — the first meeting.

When you receive a business card, be sure to follow these steps:

- Take it with both hands

- Make a show of looking at it carefully and examining it on both sides

- Put it away deliberately in your wallet or somewhere respectful—don’t shove it in your back pocket!

Make sure you bring plenty of business cards, as the exchange ritual will be repeated often.

Giving Gifts

The exchange of 礼物 (lǐ wù) — gifts is an established part of 关系 (guān xi) and an excellent way to win favor and show respect. Chances are, you’ll come home with a few new possessions, so you may feel embarrassed if you show up empty-handed.

To make sure you do it right, there are a few interesting cultural points worth mentioning:

- Receiving a gift is much like receiving a business card. Look at the package with interest and treat the object with respect. Unlike in the west, if the gift is wrapped, you aren’t expected to unwrap it then and there. Save the surprise for when you get home.

- Be aware of the cultural associations of what you’re giving. You don’t need to be paranoid about this—leeway is usually given to foreigners—but some research will pay off. Flowers are associated with funerals. Clocks and watches symbolize death, so leave that second Rolex at home. If you’re going in for wrapping paper, red is a winning color as it’s associated with wealth and success.

- Gifts from your homeland that are hard to find abroad make great gifts. It’s always a good idea to gift new business partners something interesting they can show their family and colleagues. I’m from New Zealand, so for me, toy Kiwi birds would make a good choice.

When giving a gift, you can say:

这是我为你准备的礼物。 (zhè shì wǒ wèi nǐ zhǔn bèi de lǐ wù.)

This is a gift I have prepared for you.

This clarifies that you’re giving and not just showing or borrowing the object.

How to Make a Toast in Chinese Business Culture

No affair in China is complete without a sumptuous 宴会 (yàn huì) — banquet, accompanied by an unhealthy number of toasts with China’s favorite spirit, the sorghum-based 白酒 (bái jiǔ). Sometimes misleadingly translated as “white wine,” 白酒 is typically as potent as vodka, with a strong, pungent flavor many foreigners struggle with.

While it’s not absolutely essential to participate in a toast, if the offer is made, you’d be wise to accept. The phrase you’ll hear most often is 干杯 (gān bēi). It’s used as we would use the word “cheers” in English, but means “dry glass.” It’s common to drink to health and success. The simplest formula is: 为 (wèi) — for, followed by what you’re drinking to, followed by an enthusiastic gān bēi. For example:

为更好的未来干杯! (wèi gèng hǎo de wèi lái gān bēi!)

Cheers to a better future

为合作成功干杯! (wèi hé zuò chéng gōng gān bēi!)

Cheers to our successful cooperation!

If you’ve had a few too many drinks already and the long phrases are falling off your tongue, the simple 理解万岁 (lǐ jiě wàn suì) — “long live our understanding” is a good fallback.

An interesting quirk of the toast in China is that it’s respectful to clink glasses lower down. The lower on the other person’s glass you clink, the more face you give them. This can result in hilarious situations when you chase each other’s glasses from high over your shoulder to right down to the table, with each of you humbly vying for the lower spot.

How to Bid Farewell in Chinese

It’s appropriate to express regret that your trip has ended and optimism that you’ll meet again, and that your cooperation will continue. You can do so with the word 遗憾 (yí hàn).

遗憾 expresses regret, passively blaming something unfortunate on luck or circumstances. It’s a nice way to express that you, unfortunately, have to go home, but you really don’t want to:

很遗憾,我明天需要回美国。 (hěn yí hàn, wǒ míng tiān xū yào huí měi guo.)

I regret that I have to return to America tomorrow.

Another phrase that has a similar effect is:

我不得不说再见了。 (wǒ bù dé bù shuō zài jiàn le.)

I have to say goodbye.

Like 遗憾, it connotes that the decision to leave is out of your hands. You don’t want to go, but you have to.

Why Should I Learn Business Chinese?

1.2 billion people speak Chinese (848 million people speak Mandarin Chinese), according to Ethnologue, making Chinese the most widely spoken language in the world.

Next to English, Mandarin is the top business language, according to Bloomberg Business Rankings.

Knowing a second language can increase your earning potential by as much as 10-15%, according to Ryan McMunn, President of Asian Operations at a leading U.S. manufacturing firm.

Understanding the advantage of Chinese fluency, many families go to great lengths to help their children learn Chinese, including taking their kids to China for language immersion, enrolling them in language immersion schools and hiring Chinese tutors and Chinese nannies.

Now you know some of the most important Chinese business vocabulary words, get out there and start showing off some of your new skills!

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing...

If you want to continue learning Chinese with interactive and authentic Chinese content, then you'll love FluentU.

FluentU naturally eases you into learning Chinese language. Native Chinese content comes within reach, and you'll learn Chinese as it's spoken in real life.

FluentU has a wide range of contemporary videos—like dramas, TV shows, commercials and music videos.

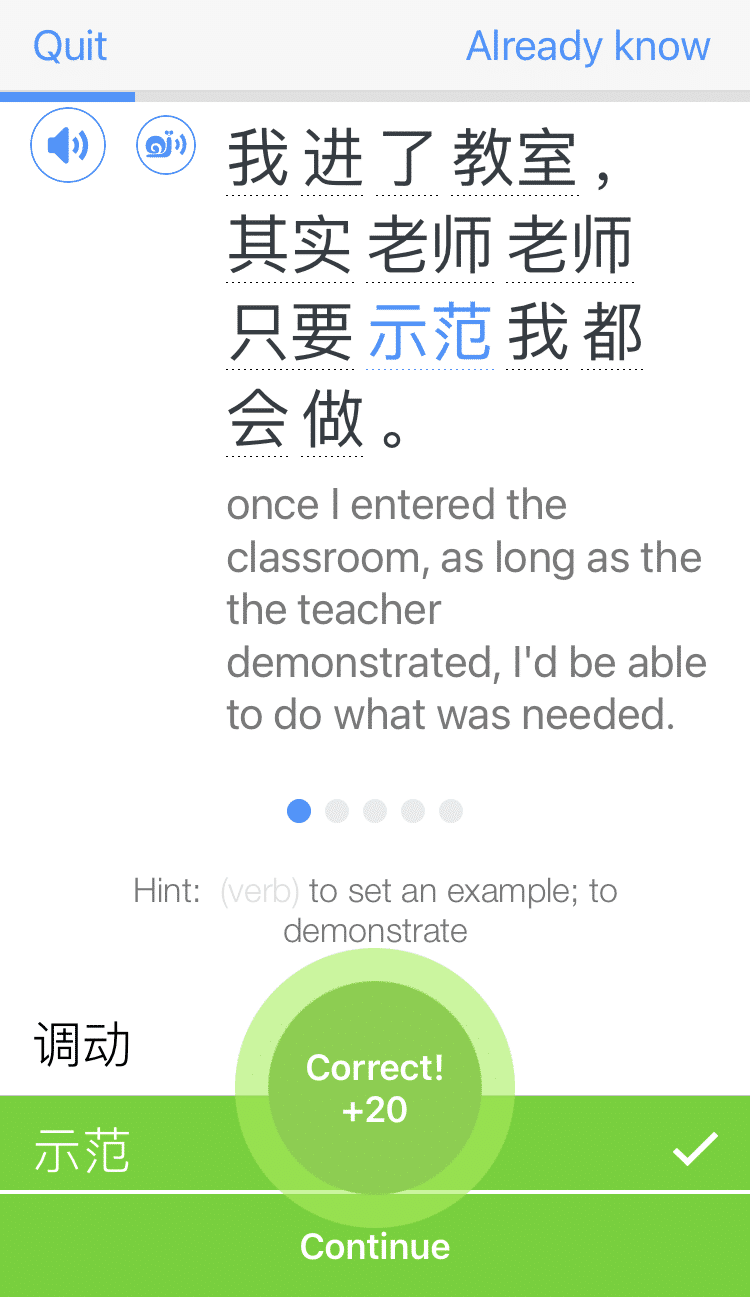

FluentU brings these native Chinese videos within reach via interactive captions. You can tap on any word to instantly look it up. All words have carefully written definitions and examples that will help you understand how a word is used. Tap to add words you'd like to review to a vocab list.

FluentU's Learn Mode turns every video into a language learning lesson. You can always swipe left or right to see more examples for the word you're learning.

The best part is that FluentU always keeps track of your vocabulary. It customizes quizzes to focus on areas that need attention and reminds you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. You have a 100% personalized experience.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)