45 Chinese Euphemisms to Help You Navigate Awkward and Taboo Topics

When you need to describe something slightly uncomfortable or unpleasant to your Chinese friends, do you know the culturally appropriate way to do so?

In other words, do you know how to use Chinese euphemisms?

Euphemisms allow us to speak about conventionally taboo topics. For example, the English language has a lot of euphemisms related to death (“passed away,” “gone to a better place”) and sex (“birds and the bees,” “getting frisky”).

In Chinese culture, it’s especially important to be wary of certain topics due to the emphasis on 留面子 (Liú miànzi — saving face). That means you don’t want to embarrass or disrespect anyone, intentionally or otherwise.

Chinese euphemisms often refer to a well-known story or historical figure and rely heavily on wordplay. For example, the phrase 她是个鸡 (Tā shì gè jī) literally means “She is a chicken,” but actually means “lady of the night.” Here, 鸡 (chicken or jī) sounds a bit like 妓 (jì), which means “prostitute.”

If that one euphemism sounds intriguing enough, wait ’til you get a load of the phrases below!

Contents

- 1. 去世了 (Qùshìle) — Left the world

- 2. 见阎王 (Jiàn yánwáng) — Gone to see Hades

- 3. 见马克思 (Jiàn mǎkèsī) — Gone to see Marx

- 4. 干掉 (Gàndiào) — Do away with

- 5. 送你上西天 (Sòng nǐ shàng xītiān) — Send you to the Western Pure Land

- 6. 自我了断 (Zìwǒ liǎoduàn) — Self-shortening

- 7. 轻生 (Qīngshēng) — Light life

- 8. 恐龙妹 (Kǒnglóng mèi) — Dinosaur’s sister

- 9. 癞蛤蟆 (Làihámá) — Toad

- 10. 发福了 (Fāfúle) — Send blessings

- 11. 啤酒肚 (Píjiǔdù) — Beer belly

- 12. 将军肚 (Jiāngjūn dù) — General’s belly

- 13. 罗汉肚 (Luóhàn dù) — Pork belly

- 14. 喝多了 (Hē duōle) — Drank too much

- 15. 喝高了 (Hē gāole) — Drank high

- 16. 神经病 (Shénjīngbìng) — Mental disorder

- 17. 脑子有问题 (Nǎozi yǒu wèntí) — The brain has problems

- 18. 笨蛋 (Bèndàn) — Stupid egg

- 19. 脑子进水 (Nǎozi jìn shuǐ) — Water in the brain

- 20. 出轨 (Chūguǐ) — Derail / Go off the tracks

- 21. 新欢 (Xīnhuān) — New happiness

- 22. 一人劈腿儿 (Yīrén pītuǐ er) — Someone has done the leg splits

- 23. 洗手 (Xǐshǒu) — Wash hands

- 24. 解手 (Jiěshǒu) — Relieve hands

- 25. 大姨妈来了 (Dà yímā láile) — Older aunt is coming

- 26. 老朋友来了 (Lǎo péngyǒu láile) — Old friend is coming

- 27. 喜事来了 (Xǐshì láile) — Good things are coming

- 28. 例假 (Lìjià) — Go on a public holiday

- 29. 发生关系 (Fāshēng guānxì) — Had relations

- 30. 上床 (Shàngchuáng) — Go to bed

- 31. 行了房事 (Xíngle fángshì) — Did room matters

- 32. 正快活着 (Zhèng kuàihuózhe) — Having a good time

- 33. 做爱 (Zuò ài) — Make love

- 34. 打野战 (Dǎ yězhàn) — Guerrilla warfare

- 35. 出台女 (Chūtái nǚ) — Coming on stage girl

- 36. 鸡 (Jī) — Lady of the night

- 37. 鸭 (Yā) — Male prostitute

- 38. 青楼女 (Qīnglóu nǚ) — Brothel woman

- 39. 站街女 (Zhàn jiē nǚ) — Standing street woman

- 40. 小姐 (Xiǎojiě) — Miss/Lady

- 41. 被炒鱿鱼 (Bèi chǎoyóuyú) — Turned into fried squid

- 42. 下岗 (Xiàgǎng) — Laid off

- 43. 待业 (Dàiyè) — Waiting for work

- 44. 赋闲在家 (Fùxián zàijiā) — Staying at home

- 45. 家里蹲 (Jiālǐ dūn) — At home squatting

- And One More Thing...

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

1. 去世了 (Qùshìle) — Left the world

One universal topic where euphemisms are often used is death, which is 死亡 (sǐwáng) in Mandarin Chinese. 去世了 is similar to the English “passed away.”

我奶奶去世了.

(Wǒ nǎinai qùshìle.)

My grandmother passed away.

2. 见阎王 (Jiàn yánwáng) — Gone to see Hades

A not-so-kind way of saying someone you dislike has died, this is similar to the English euphemism “burning in hell.”

他去见阎王了.

(Tā qù jiàn yánwángle.)

He went to see Hades.

3. 见马克思

(Jiàn mǎkèsī) — Gone to see Marx

This witty phrase can be traced back to the history of communism in China. Originally a slang phrase that Chinese communists used to refer to death, it’s now relatively common and has a slightly humorous connotation.

You could say this means the same as “joined the ancestors” and “went to meet the Maker.”

我爸去见马克思了.

(Wǒ bà qù jiàn mǎkèsīle.)

My dad went to see Marx.

4. 干掉 (Gàndiào) — Do away with

干掉 is a euphemism for “murder” or 杀死 (shā sǐ). Similar to “I’ll do away with you,” this term is a death threat. You may hear this phrase in Chinese movies and TV shows.

我把他干掉了.

(Wǒ bǎ tā gàndiàole.)

I did away with him.

5. 送你上西天

(Sòng nǐ shàng xītiān) — Send you to the Western Pure Land

In Buddhism, Pure Land is a place of bliss where people go when they die.

Sometimes, you’ll hear this when someone is fighting you and is usually uttered in a humorous way. So don’t be alarmed if you hear this from your Chinese friend!

送你上西天!

(Sòng nǐ shàng xītiān!)

I’ll send you to the Western Pure Land!

6. 自我了断 (Zìwǒ liǎoduàn) — Self-shortening

This is a gentle way to refer to suicide or 自杀 (zìshā). The English counterpart would be “she wanted to end her life.”

她想自我了断.

(Tā xiǎng zìwǒ liǎoduàn.)

She wants to shorten her life.

7. 轻生 (Qīngshēng) — Light life

Similar to the above, 轻生 is another indirect way of talking about suicide. “Light life” here means that someone values their life lightly enough to end it.

他有轻生的想法.

(Tā yǒu qīngshēng de xiǎngfǎ.)

He thinks of his life lightly.

8. 恐龙妹

(Kǒnglóng mèi) — Dinosaur’s sister

In Chinese, the concept of physical unattractiveness can be summed up in one character: 丑 (chǒu).

恐龙妹 is a relatively new phrase that’s gained popularity thanks to the internet. It’s used exclusively to refer to women, and is often uttered in the context of meeting someone in-person for the first time after communicating with them exclusively online.

别给我介绍到恐龙妹!

(Bié gěi wǒ jièshào dào kǒnglóng mèi!)

Don’t introduce me to a dinosaur’s sister!

9. 癞蛤蟆 (Làihámá) — Toad

You know how it’s said you have to kiss a lot of frogs to meet your prince? Interestingly enough, one Chinese phrase used to describe men who are unattractive (whether in looks and/or personality) is 癞蛤蟆.

他真是个癞蛤蟆.

(Tā zhēnshi gè làihámá.)

He is such a toad!

10. 发福了

(Fāfúle) — Send blessings

No one wants to be told that they’ve gained weight or 增重 (zēng zhòng).

Up until modern times, being “big” meant you had enough money to buy food. Someone with a larger build can be described as 富态 (fùtai) or “in a rich state.”

So, to say someone has gained weight, you would use 发福了 (fāfúle). Notice how the character for “blessings” or 福 (fú) appears in this expression.

他发福了.

(Tā fāfúle.)

He’s getting fat!

11. 啤酒肚 (Píjiǔdù) — Beer belly

This has the same meaning as it does in English—someone who drinks so much that it’s showing in the shape of their belly.

他这几年长了个啤酒肚.

(Tā zhè jǐ nián zhǎngle gè píjiǔdù.)

He has a beer belly.

12. 将军肚 (Jiāngjūn dù) — General’s belly

This also means “beer belly,” though the presence of the word “general” or 将军 (jiāngjūn) might soften the blow a little bit.

他这几年长了个将军肚.

(Tā zhè jǐ nián zhǎngle gè jiāngjūn dù.)

He has a general’s belly.

13. 罗汉肚 (Luóhàn dù) — Pork belly

Of the euphemisms for “beer belly” I’ve mentioned so far, this is probably the most humorous—or possibly offensive, depending on the person you’re talking to.

他这几年长了个罗汉肚.

(Tā zhè jǐ nián zhǎngle gè luóhàn dù.)

He has a pork belly.

14. 喝多了 (Hē duōle) — Drank too much

There isn’t really a politically correct way to say “intoxication” or 喝醉 (hē zuì) in Chinese. But one slightly nicer way to express the same idea is 喝多了.

他喝多了.

(Tā hē duōle.)

He drank too much.

15. 喝高了 (Hē gāole) — Drank high

Of course, it’s not grammatically correct to say “drank high” in English. But this expression and 喝多了mean the same thing.

他喝高了.

(Tā hē gāole.)

He drank high.

16. 神经病 (Shénjīngbìng) — Mental disorder

Even in English, 精神病 (jīngshénbìng) — mental illness isn’t a topic you want to talk about lightly.

神经病 is a play on 精神病, where 精 (jīng) has a similar pronunciation as 经 (jīng). As you can imagine, this isn’t the nicest thing to say about people and is often used as an insult.

他是个神经病!

(Tā shìgè shénjīngbìng!)

He is a crazy person!

17. 脑子有问题 (Nǎozi yǒu wèntí) — The brain has problems

Most euphemisms for mental illness in Chinese are negative and used to insult others. The “politically correct” way to say it would be 精神病.

Although you want to avoid using 神经病 and 脑子有问题 as much as possible, you should still be aware of what they mean in case they come up in conversation.

Aside from the literal “the brain has problems,” 脑子有问题 could also refer to someone who has done something stupid.

你脑子有问题吗?

(Nǐ nǎozi yǒu wèntí ma?)

(Does your brain have problems? / Are you stupid?)

18. 笨蛋

(Bèndàn) — Stupid egg

The Chinese language has several phrases for describing people who aren’t the sharpest crayons in the box (see what I did there?), such as 愚蠢 (yúchǔn), 傻 (shǎ) and 笨蛋.

你是个大笨蛋!

(Nǐ shìgè dà bèndàn!)

You are a huge fool!

19. 脑子进水 (Nǎozi jìn shuǐ) — Water in the brain

The imagery conjured up by “water in the brain” should be enough to tell you why 脑子进水 can come off as rude. It’s often used to describe people who are otherwise rational and suddenly do something stupid.

她脑子进水了.

(Tā nǎozi jìn shuǐle.)

Water has entered her brain. / She has done something stupid.

20. 出轨 (Chūguǐ) — Derail / Go off the tracks

In Chinese, the word for “extramarital affairs” is 外遇 (wàiyù). 出轨 is a subtler way to refer to infidelity.

她出轨了.

(Tā chūguǐle.)

She has gone off the tracks. / She has an extramarital affair.

21. 新欢 (Xīnhuān) — New happiness

This phrase refers to a new lover. It has a slightly more positive connotation than “cheating.”

我离婚因为我有新欢了.

(Wǒ líhūn yīnwèi wǒ yǒu xīnhuānle.)

I divorced because I found a new happiness (i.e., “lover”).

22. 一人劈腿儿 (Yīrén pītuǐ er) — Someone has done the leg splits

This is a slightly more comical way of looking at extramarital affairs. You can remember the meaning of 一人劈腿儿 by thinking of someone who does things that would make a gymnast blush just to be with their lover.

他们两,一人劈腿儿了.

(Tāmen liǎng, yīrén pītuǐ erle.)

Between the two of them, one of them did the splits. / Between the two of them, one person cheated.

23. 洗手 (Xǐshǒu) — Wash hands

If you want a direct way to say “go to the bathroom” in Mandarin Chinese, you say 上厕所 (shàng cèsuǒ).

But since we’re on the topic of euphemisms, you should use 洗手 instead. This can mean anything you do in the bathroom—whether it’s literally washing your hands or something else. (By the way, the Chinese word for “toilet” is 洗手间 (xǐshǒujiān), which literally translates to “washroom.”)

我要去洗手.

(Wǒ yào qù xǐshǒu.)

I have to go wash my hands. / I have to go to the bathroom.

24. 解手 (Jiěshǒu) — Relieve hands

This is less ambiguous than 洗手. It means the same thing as “relieve myself” in English.

她去解手了.

(Tā qù jiěshǒule.)

She went to relieve herself. / She went to the toilet.

25. 大姨妈来了 (Dà yímā láile) — Older aunt is coming

There are plenty of euphemisms for menstruation or 来月经 (lái yuèjīng) in Chinese.

Let’s start with 大姨妈来了.

她大姨妈来了.

(Tā dà yímā láile.)

Her older aunt is coming.

26. 老朋友来了 (Lǎo péngyǒu láile) — Old friend is coming

Sometimes, it’s an “old friend” rather than an “old aunt” who comes during “that time of the month” for a woman.

她老朋友来了.

(Tā lǎo péngyǒu láile.)

Her old friend is coming.

27. 喜事来了 (Xǐshì láile) — Good things are coming

I don’t know if “that time of the month” is “good” for every woman, but this is yet another Chinese euphemism for menstruation.

她喜事来了.

(Tā xǐshì láile.)

Good things are coming for her.

28. 例假 (Lìjià) — Go on a public holiday

This is also a subtle way to talk about a woman’s period without having to mention the exact words.

她例假 了.

(Tā lìjià le.)

She is on a public holiday. / She is on her period.

29. 发生关系 (Fāshēng guānxì) — Had relations

The Chinese term for “sex” is 性交 (xìngjiāo), and 发生关系 is one of its many euphemisms.

他们俩发生关系了.

(Tāmen liǎ fāshēng guānxìle.)

The two of them had relations.

30. 上床 (Shàngchuáng) — Go to bed

This phrase means the same thing as “slept together.”

他与她上床了.

(Tā yǔ tā shàngchuángle.)

He went to bed with her.

31. 行了房事 (Xíngle fángshì) — Did room matters

行了房事 is another way to talk about sexual relations without being too direct about it. A similar expression in English would be “doing the deed.”

他们行了房事.

(Tāmen xíngle fángshì.)

They did bedroom matters.

32. 正快活着 (Zhèng kuàihuózhe) — Having a good time

Similar to “fooling around,” 正快活着 is an informal way to describe sex.

他们正快活着.

(Tāmen zhèng kuàihuózhe.)

They are having a good time.

33. 做爱 (Zuò ài) — Make love

This means exactly the same as it does in English. Need I explain more?

昨天晚上, 我们做了爱.

(Zuótiān wǎnshàng, wǒmen zuòle ài.)

Last night, we made love.

34. 打野战 (Dǎ yězhàn) — Guerrilla warfare

打野战 is a slightly more humorous way to talk about people who “do the act” in public places. If you hear this phrase dropped in casual conversation to refer to two people—well, you’ll know better than to think that they’re talking about literal warfare.

他们去打野战.

(Tāmen qù dǎ yězhàn.)

They engaged in guerrilla warfare. / They went to have sex in public.

35. 出台女 (Chūtái nǚ) — Coming on stage girl

In Chinese, “sex worker” is 性工作 (xìng gōngzuò). 出台女, in particular, refers to a paid escort.

他请了一位出台女.

(Tā qǐngle yī wèi chūtái nǚ.)

He hired an escort.

36. 鸡 (Jī) — Lady of the night

If you’ve already learned about animals in Chinese, you may know that 鸡 means “chicken.” But because it has a similar pronunciation as the word for “prostitute,” which is 妓 (jì), you can see how this euphemism came about.

她是个鸡.

(Tā shìgè jī.)

She is a chicken. / She is a prostitute.

37. 鸭 (Yā) — Male prostitute

Similarly, 鸭 (yā) translates to “duck,” and is used to refer to male prostitutes.

他是个鸭.

(Tā shìgè yā.)

He is a duck. / He is a prostitute.

38. 青楼女 (Qīnglóu nǚ) — Brothel woman

In ancient China, 青楼 (qīnglóu) was the term for a brothel. Attach the word for “woman” or 女 (nǚ) at the end, and you can guess what 青楼女 means.

那青楼女很美.

(Nà qīnglóu nǚ hěn měi.)

The girl in the brothel is beautiful.

39. 站街女 (Zhàn jiē nǚ) — Standing street woman

This phrase refers to how some prostitutes find work. It has a slightly more negative connotation, and is similar to the English phrase “a woman of the streets” or “a woman of the night.”

她是个站街女.

(Tā shìgè zhàn jiē nǚ.)

She is a woman of the streets.

40. 小姐 (Xiǎojiě) — Miss/Lady

This is another discreet way to talk about an escort. It simply means “miss” or “lady.”

他请了一位小姐.

(Tā qǐngle yī wèi xiǎojiě.)

He invited a miss.

41. 被炒鱿鱼 (Bèi chǎoyóuyú) — Turned into fried squid

解雇 (jiěgù) means to “fire” or “dismiss” someone from their place of employment.

Getting fired feels awful for the person on the receiving end, so 被炒鱿鱼 came about as a humorous way to describe something that’s usually thought of as negative.

昨天,我被炒鱿鱼了.

(Zuótiān, wǒ bèi chǎoyóuyúle.)

Yesterday, I was fried squid. / I was fired yesterday.

42. 下岗 (Xiàgǎng) — Laid off

下岗 is a subtle and polite way to talk about people who just lost their job and is nicer than 解雇.

他们都下岗了.

(Tāmen dōu xiàgǎngle.)

They were both laid off.

43. 待业 (Dàiyè) — Waiting for work

One positive spin on being jobless or 失业 (shīyè) is saying that you’re 待业.

他这几个月在待业.

(Tā zhè jǐ gè yuè zài dàiyè.)

These past few months, he has been waiting for work.

44. 赋闲在家 (Fùxián zàijiā) — Staying at home

Another nice way of saying someone is unemployed is 赋闲在家.

她现在赋闲在家.

(Tā xiànzài fùxián zàijiā.)

She is currently staying home. / She is currently unemployed.

45. 家里蹲 (Jiālǐ dūn) — At home squatting

As you can guess from the word “squatting,” this has a slightly more negative connotation, but is still better than saying outright that someone is unemployed. 家里蹲 implies that the person who doesn’t have a job is in such a state because they’re lazy.

夫妇俩都在家里蹲.

(Fūfù liǎ dōu zài jiālǐ dūn.)

The couple is at home squatting. / The couple is unemployed.

Of course, there are many other euphemisms in Chinese for countless other topics. These are just a few of the most common ones you’ll hear thrown around.

From the embarrassing to the taboo, these phrases can help you feel a little more confident when you’re navigating everyday situations in Chinese.

You can learn more about these euphemisms through a language learning platform like FluentU.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing...

If you want to continue learning Chinese with interactive and authentic Chinese content, then you'll love FluentU.

FluentU naturally eases you into learning Chinese language. Native Chinese content comes within reach, and you'll learn Chinese as it's spoken in real life.

FluentU has a wide range of contemporary videos—like dramas, TV shows, commercials and music videos.

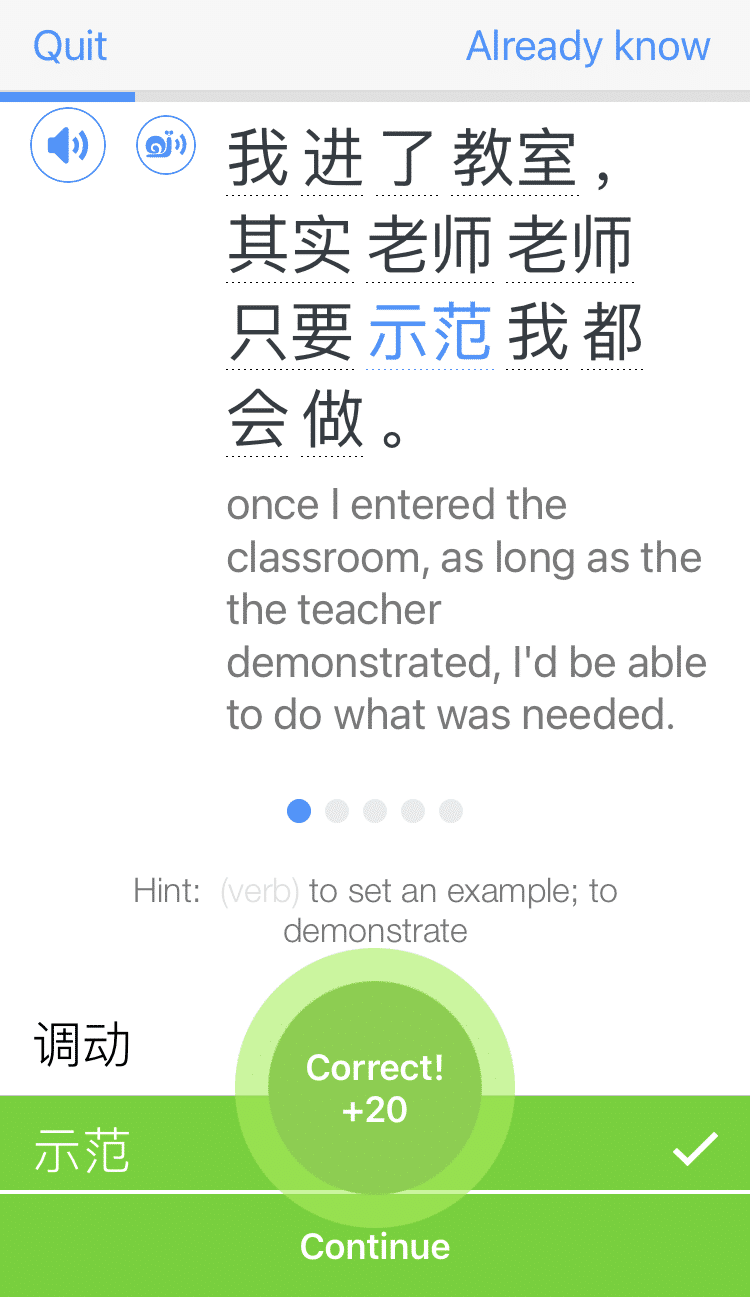

FluentU brings these native Chinese videos within reach via interactive captions. You can tap on any word to instantly look it up. All words have carefully written definitions and examples that will help you understand how a word is used. Tap to add words you'd like to review to a vocab list.

FluentU's Learn Mode turns every video into a language learning lesson. You can always swipe left or right to see more examples for the word you're learning.

The best part is that FluentU always keeps track of your vocabulary. It customizes quizzes to focus on areas that need attention and reminds you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. You have a 100% personalized experience.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)