Language Acquisition: How We Learn First and Second Languages

Language. Its acquisition is an exclusively human ability. Other species do communicate through discrete sounds and motions, but they’re not in the same class as humans.

In this post, we’ll examine the differences between first language and second language acquisition, then look at some leading theories about how children learn language.

We’ll also peek behind the curtain and talk about the five components of languages. Have you ever wondered what terms like “syntax” and “semantics” mean? They won’t be so mysterious after this!

Finally, we’ll touch on the four language skills you need to be fluent.

Let’s begin!

Contents

- Language Learning 101: What Is Language Acquisition?

- 3 Competing Schools of Thought About Language Acquisition

- The 5 Components of a Language

- The 4 Language Skills

- And One More Thing...

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Language Learning 101: What Is Language Acquisition?

First Language Acquisition

First language or native language acquisition is the process of building the ability to understand a language and use it to communicate with others. It’s how a baby grows from a wordless wonder into somebody who can’t stop talking during class.

And it starts earlier than you might think. Studies have shown that fetuses in the third trimester can hear and learn to distinguish the vowel sounds and rhythms of their native language versus a foreign language. That means they’re born primed to learn their first language!

And babies may begin to understand the meanings of common nouns as early as 6-9 months of age, before they start talking at about 9-15 months.

When you acquired your native tongue, you didn’t need a thick grammar textbook full of highlights or a long list of vocabulary to memorize.

Your learning was instinctive and unconscious. You were just living with your parents, who naturally talked to you about everything from what to eat to how to play and when to sleep. You probably can’t even remember when you started using their words back.

If you are born in Korea to parents who speak Korean with you, you’ll naturally end up speaking Korean. The same goes for whatever native language you grow up hearing.

Second Language Acquisition

Second language acquisition is the one that happens after you’ve acquired your native tongue. It builds on the existing language framework in your brain.

In contrast with first language acquisition, second language learning usually happens when you’re older, maybe inside a school or university classroom, or nowadays even a virtual one. Maybe you learn a new language because your new job requires you to speak with customers who don’t use your first language. Or maybe you just want to learn how to flirt in a new language.

Whatever the reason, the methods for learning a second language are conscious and with a purpose.

You actively study grammar from textbooks. You have your word lists and flashcards with their corresponding pictures and translations. You have apps, podcasts and YouTube videos.

Most readers of this blog are probably in this same boat, tremendously enriching their lives by learning a second (or third) language.

Who Can Learn a Second Language?

The short answer is: anyone who really wants to!

It’s true that language acquisition is most effective in the “critical period” of early childhood, when our highly elastic brains absorb language like a sponge. Afterward, it’s comparatively difficult. This has led many to believe that learning a language is the sole province of the young.

But while it’s true that our brains rapidly develop in our early years, it doesn’t lose plasticity over our lifetimes. We can create novel neural connections and learn something new at any age. That means you can embark on a language learning journey at any stage in life, your stabilized brain notwithstanding.

Studies have identified factors that exert a stronger influence than age on an individual’s language performance. For example, one study found that a person’s motivation is a better predictor of linguistic success than age.

What is it that drives you to learn the second language? What gets you over the speed bumps? Why do you do it when you could’ve done something else? These are more important than what you write in the blank after “Age.”

Quality of inputs is another factor that does better than age to predict language acquisition. That is, even if you start learning a language later in life, you can still be better off than those who started early, as long as you spend considerable time interacting with native speakers or use authentic materials in your study. The quality of inputs determines your linguistic success.

So really, it’s not that second language acquisition is only for the young or the gifted. It’s just that we need the right tools and the drive to do it.

But whether it’s first or second language acquisition, how do these processes actually take place in the mind of a language learner? Psychologists and linguists have put forth several theories over the decades to explain the phenomenon, and we’re going to look into three of the most influential ones in the next section.

3 Competing Schools of Thought About Language Acquisition

Philosophers have always been fascinated by human linguistic ability, particularly its initial acquisition.

Ever since Socrates intoned “Know thyself,” we have tried to peek behind the curtain and find out how we are actually able to learn language and use it for a myriad of communicative purposes.

Here are some theories on the matter:

1. Behaviorism (B.F. Skinner)

Behaviorism is a school of psychology that had its heyday from the 1900s to the 1950s and still holds some sway in how we think about language acquisition.

In a nutshell, behaviorism attributes animal and human behavior to cause and effect or, in other words, stimulus and response. Some responses are natural, and others are learned, or conditioned.

For example, salivating is a natural response to the stimulus of food, but not to hearing a doorbell. However, if you like to order in a lot, you might learn that the sound of your doorbell means your food has arrived. If you start salivating at the sound of that bell, congratulations! You’ve been conditioned to associate the doorbell with food.

B.F. Skinner, an eminent behaviorist, proposed that language acquisition is really one big and complex case of conditioning.

According to behaviorism, babies first learn the meanings of words via association. If a baby hears the word “milk” often enough right before being fed from the bottle, he’ll soon associate the word “milk” with drinking milk. If he always hear the word “ball” right before being handed a spherical object, he’ll begin to associate “ball” with the object.

A baby will then learn to use words by imitating the adults around them. At first they just babble, but when they make the right sounds, their parents will react by smiling, praising them or giving them what they want. Getting a reward for a correct behavior is a form of conditioning called positive reinforcement.

The child continues to learn the correct form of his language by trial and error, receiving positive reinforcement (a reward) when he uses correct grammar and negative reinforcement (lack of reward) or correction when he gets it wrong.

In the behaviorist view, language is simply reinforced imitation.

2. Universal Grammar (Noam Chomsky)

In the 1960s, the field of behaviorism came under serious attack from the likes of Noam Chomsky, a man recognized as the father of modern linguistics, and about as decorated a scholar as any.

He pointed out that if you look closer, parents really give very little linguistic input for tots to imitate directly. Chomsky argued that parent-child interactions are limited to repeated utterances of things like “Put that back” and “Open your mouth”—not very likely to make significant dents towards the cause of language learning. And besides, when a child says, “I swimmed today,” he didn’t get that from any adult figure in his life. That’s not imitation.

So how does one account for the fact that children learn to speak their native tongues in spite of the “poverty of the stimulus”? One is left with the conclusion, Chomsky argues, that if not from the outside, external input, then the ability must have been there all along.

Chomsky asserts that human beings are biologically wired for language—that we have a “language acquisition device” that allows us to learn any language in the world. Linguistic ability is innate to us.

Proof of this are the emergent abilities that have no external source. For example, how do children make out the individual words in the strings of sounds that they hear? Reading and writing are learned later, so they can’t have worked it out by seeing separate words on a page.

Chomsky would argue that children use this “language acquisition device” to figure out the rules specific to their native language. He even goes on to assert that there is such a thing as a “Universal Grammar.” For how else did the different languages end up with the same categorization of words (nouns, verbs, adjectives, etc.) when there’s an infinite number of ways words can be categorized? We always have nouns, verbs and adjectives.

Chomsky’s work represented the “nature” side of the “nature-nurture debate,” while the behaviorists account for language as part of “nurturing.”

Of course, because of its sweeping and seemingly simplistic assertions, Chomsky’s theory has its own set of strong dissenters. Let’s talk about them next.

3. Cognitive Theory (Jean Piaget)

Your churning brain might already be asking any number of questions:

“So what proof do we have for this ‘language acquisition device’? Where in the brain is it located? Can we see it in action?”

“Have we studied all the languages of the world to conclude that there is indeed ‘Universal Grammar’?”

These and other queries prompted a whole different approach to the question of language acquisition. And as is often the case, subsequent theories point out the weaknesses of those that came before them.

Chomsky’s theory did that to behaviorism, and in turn, those that follow will try to fill in the gaps. And instead of taking a side on the nature-nurture debate, the cognitive theory of language acquisition recognizes that both processes have their roles to play.

The psychologist Jean Piaget is a major proponent of this cognitive model, which sees language acquisition in light of developing mental capacities. The idea here is that we’re able to learn language because of our ability to learn. It’s because of our cognitive development. Our brains become more complex, and we learn so many things so fast.

Babies initially don’t talk because their brains and mental capacities still lack the experience and scaffolding necessary for language. But as babies grow, as they interact with adults, as they gain more experience, as they observe more things and as they learn more concepts, language becomes the inevitable result.

Piaget believed that the understanding of concepts must come before language. When a child says, “Ball is red,” he must first understand what a ball and the color red are before he can comment.

So if you notice how language develops, it follows the complexity of our thinking. The more nuanced and layered our thinking, the more textured the language that comes out. That’s why children talk one way, and adults talk a different way.

In this model, language is seen as part of our advancing mental capacities—alongside our ability to reason or to think in the abstract. We are rational beings, information processors that interact and learn from experience.

Those are three of the most influential theories on language acquisition. Each has its merits and each gives a certain view of how we learn language. Needless to say, more research and study is needed on the topic. There’s still so much to discover, and so much to learn in this area of linguistics.

When we say “language acquisition,” what is it exactly that we acquire? Well, we now go to the next section to find out.

The 5 Components of a Language

Here we get into the nitty-gritty of languages, and look under the hood to see their basic parts.

Languages are governed by rules. Without them, the utterances of one person would be random and meaningless to anyone else.

We need to meet the rules languages follow, behind the scenes, in order to have a proper appreciation of them. I’m talking here about the five components of a language: syntax, semantics, phonology, morphology and pragmatics. Whatever language you’re considering, it has them.

1. Syntax

Syntax is how words and phrases are arranged to create a grammatically correct sentence within a language. It also encompasses the parts of speech and other categories words and phrases can occupy.

Because of the specific ways the elements of speech are arranged, we can decipher meaning and understand each other. For example, take the English sentence: “The dog saw the cat.”

English uses subject-verb-object syntax. Thus, we know the dog is the subject of the sentence and the cat is the object. The verb “saw” is what the dog did and what was done to the cat.

If the sentence were written, “Saw the dog the cat” or “The cat the dog saw,” we’d have a heck of a time figuring it out, because it doesn’t follow English syntax rules.

But what is a dog, and what is seeing? The meaning of words is the subject of the next category.

2. Semantics

Semantics is all about meaning in a language—what words, phrases and sentences actually signify.

“Shoulder,” for example, is a noun that signifies the part of human anatomy where an arm connects to the body. Its semantic properties include: “connection of forelimb to body,” “outsidemost part,” “burden-bearing part” and more.

We can talk about “a pork shoulder roast,” “the shoulder of the highway” or “shouldering a responsibility” and still be understood, because the word retains its semantic properties across contexts and parts of speech.

But we can’t say shoulder if we mean tree, because they don’t share semantic properties.

In addition to single-word semantics, there are phrase and sentence semantics. These work hand in hand with syntax because different arrangement of words can create different meanings. For example, we have a sentence:

“She tapped him on the shoulder.”

Let’s say we’ll insert the word “only” somewhere in the statement. Notice how this changes the whole meaning and complexion of the statement, depending on where exactly we place a single word.

She only tapped him on the shoulder. (She didn’t punch him.)

She tapped only him on the shoulder. (Nobody else got a similar treatment.)

She tapped him only on the shoulder. (Not on his head or anywhere else.)

Meaning can change depending on how you arrange specific words. And not only that, meaning can also change depending on the form of individual words. Let’s talk about that next.

3. Morphology

Morphology is about the form of words. It’s best observed in the written form of a language. Change in form often brings with it a change in meaning.

Root words—the most basic word forms—can be modified with prefixes and suffixes to form new words, each with a different meaning. A single root word can give birth to many new words, and that’s where the linguistic fun begins.

Take the root word “drive.”

Add “r” at the end and you have “driver.” From a verb, your word has become a noun, a person.

Next, add “s” to your newly formed word and you have “drivers.” You’ve just turned a single person into multiple people by using the plural form of the word.

Change “i” to “o” and you have “drove.” From a verb in the present tense, you introduced a time change and turned it into a past tense.

You can do many things with the root word “drive” and come up with new words like:

- driven

- driving

- driveable

- driveability

- overdrive

- microdrive

And so on.

That’s what morphology is all about. Different meanings come from different word forms. Speaking of forms, when spoken, each of these new words will inevitably sound different. That’s what the next language characteristic is all about.

4. Phonology

Phonology is the study of linguistic sounds. And if ever you want to be considered fluent in your target language, you have to be very familiar with the intonations, stresses, pauses, dips and tones of the language.

To sound like a native speaker, you have to pronounce words, phrases and sentences like they do. There are specific sounds and sound patterns that exist in a language. For example, Spanish, Italian and Portuguese have rolling “R’s” that give some English speakers a heck of a time.

In languages like Italian, you oftentimes only need to look at how a word is spelled (morphology) in order to know how it should be pronounced. In other words, in those languages there’s a close correspondence between the language’s written form and its spoken form.

In the case of English, though, if you could guess the correct pronunciations of words like “though,” “rough” and “bough” and based on spelling alone, you’d stand a good chance of winning the lottery, too.

5. Pragmatics

Pragmatics is concerned with how meaning is negotiated between speaker and listener. This is the part of language that is not spoken, but implied based on context. It’s how we can say one thing and mean another.

When your boss, after reading your submitted proposal, tells you, “This won’t work. Go back to square one,” you begrudgingly know what he means. You don’t take his words literally and look for “square one.” You start again.

Or when you’re hours late for a date with your wife and she asks you, “Do you know what time it is?” you know better than to give her the exact time. You know a rhetorical question when you hear one.

Pragmatics lends languages levity, so we don’t get stuck with being so literal all the time. You know you’re fluent in a language when you understand idiomatic expressions, sarcasm and the like.

Now that we know about the five characteristics of languages, we get to the four modalities in which language acquisition can be judged: listening, speaking, reading and writing.

The 4 Language Skills

How do you know if or when you’ve acquired a language?

That’s a difficult question to answer. When you get down to it, language acquisition isn’t an either-or kind of thing, but rather a continuum, and language learners stand at various stages of acquisition.

And to make things a little bit more complicated, there are four basic language modalities or skills involved: listening, speaking, reading and writing. They’re closely related, but still clearly different. You may have thought of “language acquisition” in terms of speaking ability, but it’s just one of four competencies considered.

Let’s look at them.

Listening

We know that listening is the first language skill to be developed. Before babies can even talk, they’ve already logged serious hours listening. They listen to how their parents talk, to the intonations and pauses, and take their cues as to the speaker’s emotions.

Babies have this “silent phase” when they simply give you those cute bright eyes. No words are spoken. But you know something is happening inside those brains because one day, they just start babbling—something unintelligible at first, then gradually moving into their first words, like wooden sculptures slowly arising from individual blocks of wood.

Listening has often been mistaken for a passive activity, where you just sit there and orient your ears to the audio. You can even sleep if you want to. But nothing is further from the truth.

To listen effectively, you have to be actively into it. You need to listen for specific things: intonations, motivations, emotions, accents and the natural flow of sound.

A language has a specific musicality unique to it. It’s not just about vocabulary. To be fluent, you need to be aware not only of the words but also of the sounds of those words. And the only way you can hone this skill is by investing the time into listening to both authentic sources and study materials.

You can for example use an audio-based study program like Pimsleur. Listen to it on your commute. For authentic material, you can get podcasts produced by your target language’s native speakers.

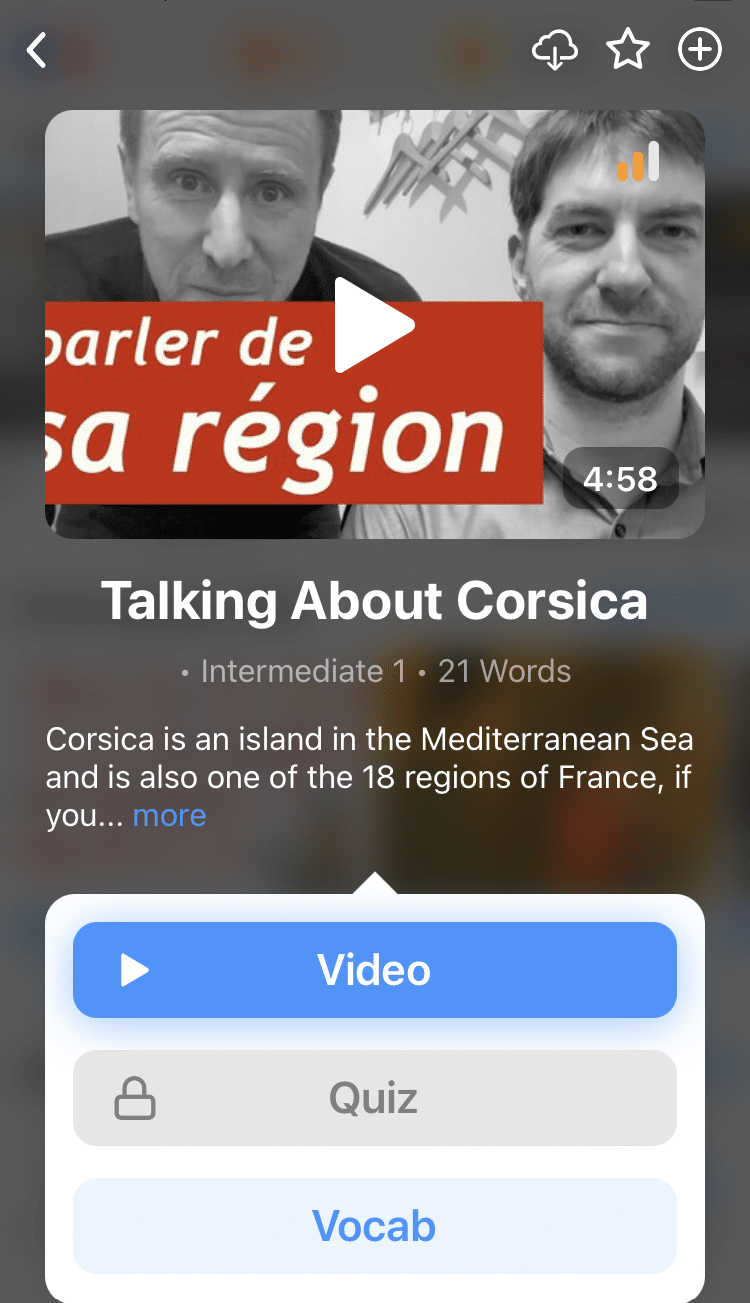

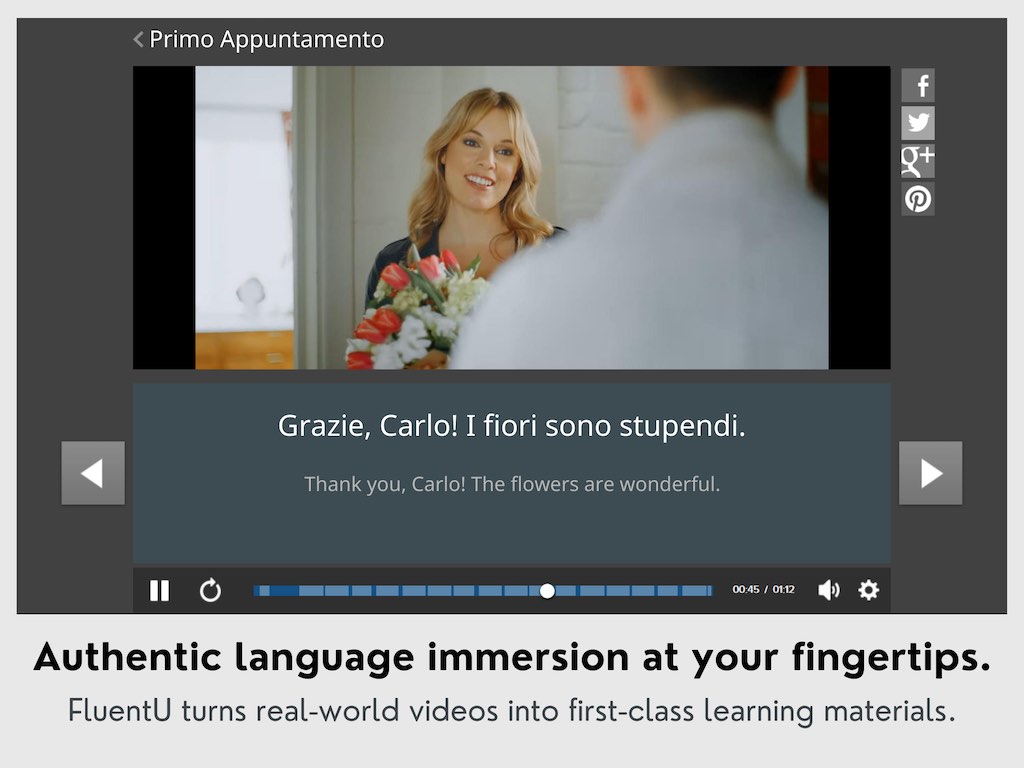

And just because you’re listening doesn’t mean you have to limit yourself to audio. There are language learning programs like FluentU that offer authentic videos of all sorts.

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

At first, you don’t need to go for complete comprehension of what you’re listening to. Heck, you don’t even need to work out the individual words. Close your eyes and consciously notice the dips and rises of the tone. Notice, for example, how the tone evolves from the beginning of a sentence to how it ends.

You have to invest time in this. That is, you do if you want to sound like a native speaker.

Speaking

Speaking is probably what you think of when we mention “language acquisition.” It is, after all, the most vivid proof of your linguistic chops. There’s nothing like speaking fluent Mandarin to impress a date—never mind that what you actually said was the equivalent of “Where’s the bathroom?”

Ironically, although speaking may be the end goal for many language learners, many devote very little study time to it. Many learners instead dive deep into vocabulary and grammar.

I’m not saying you shouldn’t do that. Vocabulary helps on all fronts—listening, speaking, reading and writing. But it doesn’t score a frontal hit on the main goal of speaking.

The thing that stops language learners is usually embarrassment. Even when we’re totally alone, we’re worried that somebody from far away might hear us butcher the pronunciation of a single word. You don’t want to mess it up, so you put it off, focusing on word lists, perfect grammar or anything else to avoid opening your mouth.

But the truth is that messing it up is a necessary step on the road to getting good, and it’s nothing to be ashamed of.

Babies don’t have those hangups. They babble away, butchering their mother tongues all day long, while their egos remain intact. Is it any wonder why they acquire their language so easily?

Speaking is a physical phenomenon, so you need to actually practice getting your vocal ensemble—your tongue, mouth, teeth and palate—to move the way native speakers move theirs. You need to feel what it’s like saying those words. You need to hear yourself speak.

To learn to speak, you need to open your mouth. There’s just no way around it.

Reading

Being able to read in a second language opens up a whole new world of literature to you.

Imagine being able to read “The Three Musketeers” in the original French or Dante’s “Divine Comedy” in the original Italian. There’s just nothing like a helping of those works in the language in which they were written, because there are some things that just can’t be adequately translated.

Thankfully, all your time studying vocabulary and grammar rules works in favor of reading comprehension.

In addition, you can gradually build your comprehension prowess by starting off with dual-language books. These are books that give you a line-by-line translation of the story. You can compare and contrast the languages as you go along.

Next in this build-up would be children’s books in the target language only. Children’s books will be easy enough for you to read. Choose stories you’re familiar with so you can do away with plot-guessing and focus on learning.

And remember, just to practice moving your mouth in the target language, try reading aloud the text in front of you. That way, you’re hitting two birds with one stone.

Writing

Many consider the ability to write in another language the apex of language acquisition. Maybe they’re thinking about writing in terms of epic volumes, academic in nature, read and revered by one generation and the next.

Here we’re talking about writing in more prosaic terms.

Writing, in many respects, can actually be easier than speaking the target language. With the written form, language learners actually have a visible record in front of them. Written texts are more malleable than spoken words. You can scratch written texts, reorder them and correct their tenses and conjugations.

Again, vocabulary and grammar training help a lot to build this skill.

In addition, you can practice writing by doing short paragraphs on things like:

- My Perfect Day

- My Secret Hobby

- Why I love “Terminator 3”

Your work may not become a fixture in the language classes of the future, but the cool thing about writing is that the more you write, the better you become at expressing yourself in the target language. This inevitably helps in honing the other communication skills, like speaking on the fly, understanding content written by others and listening to native material.

Now you know a lot about language acquisition—from the theories about it, to the differences between native language and second language acquisition, to the five characteristics of languages and the four linguistic skills to hone. I’m hoping that, if anything, this piece has sparked more interest and desire in you to learn the languages of the world.

Happy learning!

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing...

If you dig the idea of learning on your own time from the comfort of your smart device with real-life authentic language content, you'll love using FluentU.

With FluentU, you'll learn real languages—as they're spoken by native speakers. FluentU has a wide variety of videos as you can see here:

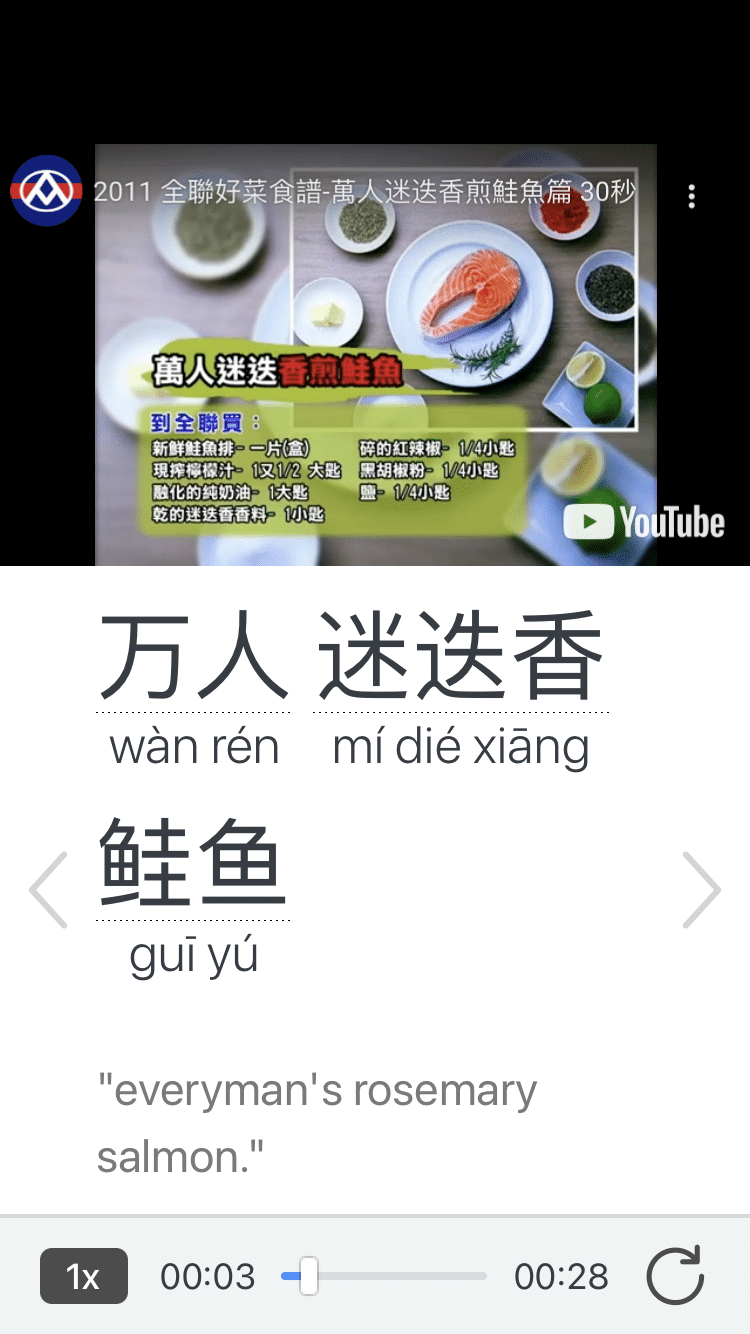

FluentU has interactive captions that let you tap on any word to see an image, definition, audio and useful examples. Now native language content is within reach with interactive transcripts.

Didn't catch something? Go back and listen again. Missed a word? Hover your mouse over the subtitles to instantly view definitions.

You can learn all the vocabulary in any video with FluentU's "learn mode." Swipe left or right to see more examples for the word you’re learning.

And FluentU always keeps track of vocabulary that you’re learning. It gives you extra practice with difficult words—and reminds you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. You get a truly personalized experience.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)