Russian Grammar

Learn Russian grammar naturally with FluentU, an effective way to turn anything from music videos to cartoons into compact and powerful video lessons. You’ll find yourself absorbing pronunciation, possessive pronouns and more after using the program.

How to Learn Russian Grammar Rules

Basic Rules Rule!

The Pareto principle states that you get 80% of your results from just 20% of the work. This concept is very important to keep in mind when you learn Russian grammar. While you will need some familiarity with the rules behind any foreign language you learn, you don’t have to know as much as you might think.

Beginners especially should just learn enough Russian grammar to get by at first. If you’re talking with someone who barely speaks any English, you can still understand a sentence like “I go store” even though the grammar is pretty awful. The same applies to the Russian language because native speakers will usually understand what you mean even in broken Russian grammar.

A key thing you need to do is to not spend too much time on Russian grammar.

Sure, it’s an important aspect of language learning, but lots of other skills need your attention first. It doesn’t matter if you know Russian grammar backward and forward if your vocabulary isn’t big enough to really use it. And if you speak with a strong accent, you might not even be understood at all.

Start Learning in Context

The easiest way to learn Russian grammar is by absorbing it naturally and contextually.

Think about it. What got you prepared to speak the English language?

While your time in school probably improved your grammar and vocabulary somewhat, you were already more than fluent in English before you ever set foot in a school. You learned your mother tongue through actually using it and hearing it spoken, not from poring over a textbook at all hours of the night. Apply this same principle to Russian grammar.

One great tool you can use to accomplish this kind of immersion is authentic Russian mass media. This can include songs, books, movies, or whatever else you enjoy consuming in English.

FluentU takes all kinds of native-level videos and turns them into Russian lessons. The program will help you learn Russian grammar naturally as you watch native speakers use it in a variety of contexts.

To really maximize the benefit of mass media for absorbing the Russian language, use it in conversation. While trying to conjugate verbs that you’re not even sure exist can give you a bit of a headache, you will find your proficiency in Russian grammar expanding far more rapidly.

If setting up a language exchange sounds appealing to you, you need to set up some ground rules with your partner. This can include how the time is divided between the two of you, whether or not you correct each other after a grammar mistake and how much time you spend on the nuts and bolts of Russian grammar itself (i.e. exploring all the different tenses, irregular Russian verbs, Russian prepositions, you name it).

Practice, Practice, Practice

Your decision to learn Russian will have plenty of positive effects on you; one of them is improving your patience and humility. Much like other skills, you can’t learn Russian overnight.

It takes time for correct Russian grammar to become second nature. Eventually, you will get to the point of knowing the right way to say something just because, not from some long list of memorized rules.

The way to get there fastest is to practice being uncomfortable. Don’t close the tab yet! There’s a good reason for saying that.

While the recommendation to use Russian in conversation can technically be fulfilled by doing so once every few weeks, that’s not going to help you improve all that much. Instead, make a Russian conversation a part of your study routine, doing so a couple of times a week if possible.

Full disclosure: your brain will hurt in a way that you never knew was possible. In some ways, it’s a lot like feeling sore after a workout. Sure, it’s unpleasant, but you can feel good knowing that you’re improving your strength and ability.

Ease into It: The Simplest Elements

Do Away with “The” and “A”

Russian grammar has no articles. That means you can take any noun (bicycle, for example) and use it as either “the bicycle” or “a bicycle” without changing it at all and without putting another word in front of it.

This can be a relief for some students, especially those who have contended with the der, die and das of German. While you will have to avoid ambiguity, it’s yet another thing that you don’t have to worry about learning over again in Russian!

Sentence Structures Are Flexible

In Russian grammar, word order is fairly loose, which means there are plenty of different ways to say the same thing.

You can say “the grandmother went to the theater,” “to the theater went the grandmother,” or “the grandmother to the theater went,” just to name a few. Each form has different nuances in its meaning and what part of the sentence it emphasizes, which gives Russian grammar a particularly expressive quality to it.

To get a better feel for this, try reading some of Alexander Pushkin’s poetry. He is considered to be the best Russian poet of all time, and native speakers will be deeply impressed if you can recite a line or two from his work.

Try starting with one of his most famous poems, “Зимнее Утро” (Winter Morning). While the Russian is a bit archaic, you’ll still be able to pick out its meaning and see how he plays around with each string of words to produce some of the most beautiful poetry ever written in the Russian language.

While Russian grammar rules and the Russian language as a whole can feel very stringent and controlling at times, it is little loopholes like these that make the whole thing feel worthwhile and possible.

Concise Conjugation

Russian verbs change form based on who is performing the action. Let’s take a look at how this works, using the verb думать (to think).

- Я думаю (I think)

- Вы думаете (You think — formal, plural form)

- Ты думаешь (You think — singular)

- Он/она думает (he/she thinks)

- Они думают (they think)

- Мы думаем (we think)

As you can see, the verb itself alters based on the person doing the action. This doesn’t sound exactly sound like good news, at first!

But this structure actually lets you take some fun linguistic shortcuts and improve your overall clarity.

How so?

It’s much easier to figure out who someone is talking about when telling a story because you get a reminder every single time they use the verb. You can even cut out the Russian pronouns entirely in many instances. Instead of saying я могу это сделать (I can do that), you can get away with simply saying могу instead.

Russian Isn’t as Foreign as You’d Think: Similar to Romance Languages

Russian Nouns and Gender

The Russian language is gendered; which may sound very familiar to many or downright confusing to others.

Like many other languages (such as Spanish or French), Russian nouns have a gender assigned to them. They fall into three categories.

- Masculine nouns

- Feminine nouns

- Neuter nouns

If your language learning has ever involved another gendered language, this won’t be too difficult to pick up. While it can take a bit of effort to wrap your head around the rules for these three genders, it will come with time and patience.

- Masculine nouns ending (singular): й or a consonant

Masculine nouns ending (plural): ы or и - Feminine nouns ending (singular): я or а

Feminine nouns ending (plural): ы or и - Neuter nouns ending (singular): е, ё or о

Neuter nouns ending (plural): а or я

Russian Adjectives and Gender

Russian grammar rules dictate that you have to match your adjective gender to your noun gender.

Fortunately, this isn’t too difficult because adjectives in the nominative case tend to follow a certain pattern. Here’s an idea of what to look for:

- -ый (masculine)

- -ая (feminine)

- -ое (neuter)

- -ые (plural)

Note: While “plural” isn’t actually a gender, it should be learned as such because these Russian adjectives have their own distinctive ending for it.

The Brand New: Unfamiliar Concepts to Conquer

The Case System

There’s no getting around it. The Russian case system is no piece of cake and has caused some students to wish they hadn’t chosen to learn Russian, but that isn’t going to be you! While learning this particularly difficult element of the Russian language is something you’ll want to put in the past tense rather quickly, it doesn’t have to be as hard as you’d think.

It’s important to remember that the case system is to Russian grammar what sentence structure is to English grammar. Each particular case plays a particular role in making the message expressed logically. The flexible sentence structure mentioned earlier is made possible by this.

It’s not as bad as you think. Russian only has these 6, but Finnish has 15 cases! Obviously, it could be much worse.

While the Russian case system can feel downright painful, the key is to not let it stress you out.

As was said at the outset, learn Russian grammar to get by but not to the point that makes you feel worried about it. Understand enough about it to intelligently deconstruct sentences in an authentic context, and figure out why they’re put together in a certain way. Don’t study it so much that you give yourself a headache.

Here is a brief overview of all six cases and what they do:

Именительный падеж (Nominative case)

- Answers Кто?/Что? (Who?/What?). This case is the one you’ll find in dictionary definitions and is used for the subject of a sentence.

- Example: Картина висит на стене. (The painting is hanging on the wall.)

Винительный падеж (Accusative case)

- Answers Кого?/Что? (Whom/What?)

- This case is used for the direct object of a sentence that the action is performed on.

- Example: Она дала книгу Наташе. (She gave the book to Natasha.)

Дательный падеж (Dative case)

- Answers Кому?/Чему? (To whom?/To what?)

- This case is used for the indirect object of a sentence.

- Example: Она дала книгу Наташе. (She gave the book to Natasha.)

Родительный падеж (Genitive case)

- Answers Кого?/Чего? (Whose?/Of what?)

- This case is most often used to denote possession of something, like “‘s” is used in English.

- Example: Дайте мне балалайку студента. (Give me the student’s balalaika.)

Творительный падеж (Instrumental case)

- Answers Кем?/Чем? (With whom?/With what?)

- This case serves to indicate what you used to complete the action in question. When used with the preposition с, it means you did it with something/someone.

- Example: Я писала письмо карандашом. (I wrote a letter with a pencil.)

Предложный падеж (Prepositional case)

- Answers Где?/О ком?/О чём? (Where? About whom? About what?)

- Buckle up for a shocker: you use this case with prepositions. Who could have seen that coming, right?

- Example: В доме есть собака. (There is a dog in the house.)

Why Is the Russian Case System Important to Understand?

Now that you know what the six Russian cases are, it can help to learn why using them correctly is so important. Let’s look at the following scenarios to get a better understanding of why they matter so much in Russian grammar.

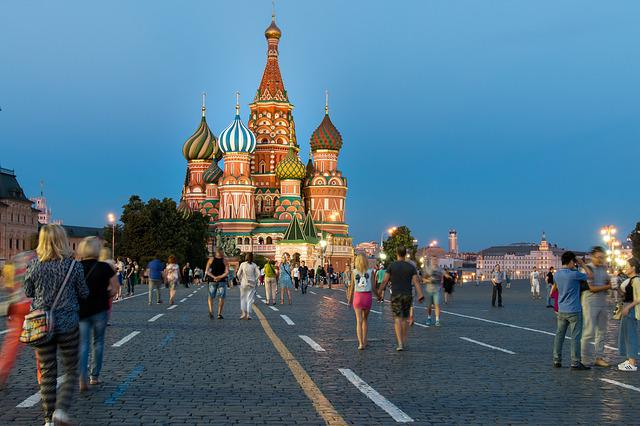

Scenario 1: You decided to fly to Moscow on a whim and surprise your best friend. What text message do you send him to let him know you’re in his hometown?

- Я сейчас иду пешком в Москву. (I’m walking to Moscow now.)

- Я сейчас иду пешком в Москве. (I’m walking in Moscow now.)

As you can see, the first option would have left your friend more than a bit confused and likely worried about your sanity (especially if you don’t live on the same continent!).

The second option would alert him that you’re in fact, strolling around the streets of Moscow and seeing the sights.

Isn’t amazing how using the accusative case instead of the prepositional case (which amounts to just one syllable of difference in this instance) can change so much?

Scenario 2: Now that you’re in Moscow, your best friend has offered to let you stay with him and his wife, Dasha. Sitting at the breakfast table, you want to ask him to pass the oatmeal (porridge) to his wife. What do you say?

- Дай каша Даша. (Give porridge Dasha).

- Дай каше Дашу. (Give Dasha to the porridge).

- Дай кашу Даше. (Give Dasha the porridge).

The first request is in broken Russian grammar, and both nouns are left in the nominative case, but your friends will probably understand it to mean that you’re asking Dasha for the oatmeal/porridge.

The second option will likely leave your friends quite bewildered and may even start wondering why they let you into their home in the first place.

Only the third option will convey the desired message. The only thing differentiating the last two choices is that the accusative case and dative case are used in opposite words.

Scenario 3: Now that you’re back home, you decide to write your friend a note thanking him for his hospitality. Before long, you find yourself rambling via pen about your latest excursion into making borsch. Of course, no good borsch story is complete without a tale of how you beat the beets (or how they beat you!) when trying to prepare them for cooking. Which sentence should you use?

- Я порезал свёклу ножом. (I cut the beets with a knife).

- Я порезал свёклу с ножом. (I cut the beets with a knife).

Feeling baffled? This is a tough one. In both instances, the word “knife” is correctly in the instrumental case. To make matters worse, the translations are identical! This is where looking at the details makes a difference.

The second option uses the preposition с whereas the first one does not. Look back at what was said in the explanation of the instrumental case; it can be used for two different purposes.

Figured it out now? The first sentence indicates the obvious, that you used a knife to slice the beets. The addition of that short little word с, though, changes things in the second sentence. Because of it, the phrase now means that you cut the beef while your knife was with you, presumably somewhere in the nearby vicinity.

While most Russians will understand how battling beets into borsch is no easy feat, your implication that you did so without actually using an available knife will be quite astounding to them. Needless to say, misrepresenting your skills in this regard might not work out for the best in the long run.

There you have it, three scenarios demonstrating how using the wrong case can get you in trouble.

Use that knowledge to conquer them like the Russian learning champion you are!

Try Our App Today

Get all six Russian cases firmly under your belt with FluentU, a fantastic way to learn Russian from an audio-visual authentic context.

With our expansive library of native-level Russian videos, you’ll find yourself absorbing the cases with ease. You’ll be getting compliments on your grammatical proficiency before you know it.