How to Understand Spoken French Through 3 Surprisingly Simple English-language Practices

I have a bit of an unconventional way to help beginners better understand the structure and sound of spoken French.

The trick is to use English!

So here are three simple English practices we already do, which will help to open up your ears to the French language such that you have a new, clearer understanding of it.

Contents

- 1. Speaking with Relaxed Pronunciation

- 2. Keeping Subject Pronouns

- 3. Comparing to Early Modern English

- And one more thing...

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

1. Speaking with Relaxed Pronunciation

You’d be lying if you said you’ve never spoken in relaxed pronunciation, because we all uncontrollably do it in comfortable, informal scenarios.

So What Is Relaxed Pronunciation?

It’s the phenomenon of when a speaker joins syllables of words together to create one single word, resulting in a type of verbal slang that’s considered informal and non-acceptable when written.

Here are a few examples of relaxed pronunciation in English:

- Give me – “gimme”

- Should have – “shoulda” or “shoulduv”

- Let me – “lemme”

- Got to – “gotta”

Clearly this style of speaking is not “correct,” but whether we’d like to admit it, it is natural.

Think about it like this: Sound is essential.

When a foreigner goes to an English-speaking country, do you believe it’s easier for them to be understood by straining each and every syllable of a sentence, or rather, to jumble words like “got to” into one sounding word: “gotta.”

Naturally, “gotta” rolls off the tongue nicely for both English natives and English language learners. Even though “gotta” is considered wrong, the way it sounds is not.

Keep in mind that relaxed pronunciation is a verbal phenomenon, not a written one. No one should ever write like this, unless you’re texting, messaging online, writing dialogue or blogging for personal purposes.

Relaxed Pronunciation in French

In verbal French communication relaxed pronunciation also occurs, but in other parts of speech and sentence structure.

Here’s a quick example to start: un petit peu → un p’tit peu (a little bit).

It’s an expression every French learner knows, but in France you’ll mostly hear it said like this: un ti peu. Just remember to say it really fast like we say “shoulda,” in one word: un-ti-peu !

Now we’ll look at a bigger structural relaxation in verbal French, which involves negation.

Do you remember being taught in basic French class to always use ne and pas together when expressing negative instances?

Well, hate to break it to you, but a lot of French natives leave out the ne entirely while keeping pas when they speak.

Here, let’s look at some common relaxed pronunciation examples in French where ne is omitted:

Je ne sais pas → je sais pas / j’sais pas [Sounds like: chépa]

(I don’t know)

Ce n’est pas grave → c’est pas grave [Sounds like: sépa grave]

(It’s no big deal)

Je n’ai rien fait → j’ai rien fait

(I didn’t do anything → It wasn’t me)*

Je ne crois pas → je crois pas

(I don’t believe)

*Note: Je n’ai rien fait / j’ai rien fait is a special case because it conveys a separate meaning when you drop the ne, unlike the other examples.

The Literary “Ne”

Quick detour here: You may be wondering if there’s a way to omit pas and keep ne instead. Of course there is! But it’s not considered relaxed pronunciation. It’s a style of formal speech that’s used by the French to be intentionally lyrically “fancy,” which is kind of the complete opposite of this verbal slang I just shared with you.

So that you get a taste of both worlds, here’s what the other side of the “fancy” negation spectrum looks like:

- Je ne sais quoi faire.

(I don’t know what to do.)

Instead of: Je ne sais pas quoi faire.

- Je ne puis vous répondre.

(I can’t respond to you.)

Instead of: Je ne puis pas vous répondre.

In the first part of both examples, pas is missing. A lot of it has to do with the way things sound. Omitting pas is selective, and according to the French, it’s an older, sophisticated, “rich” way to speak (randomly and scarcely used by the higher class/society).

Quite unlike its relaxed pronunciation counterparts, it is permitted to be written and expressed on paper (this is known as ne littéraire). Take heed of certain verbs though! The removal of pas doesn’t work for all of them. You can learn more about this concept on Lawless French. You can also hear examples of this in use by native Frech speakers by watching authentic French videos with interactive captions on the FluentU program.

Keep in mind that the majority don’t speak like this anymore. Rather, omitting ne (with relaxed pronunciation) is much, much more common and popular, despite its informality.

Okay! Enough with the confusion! Back to relaxed pronunciation.

When Is Relaxed Pronunciation Used in French?

Similar to English, relaxed pronunciation is used in French in everyday verbal speak—radio talk shows, movies, music, etc.—and on the Internet: blogging, messaging or even phone texts.

Also as in English, when written it’s considered informal and unacceptable. If you would never write a college term paper using “gotta,” then don’t do it in French either!

How to Listen for Relaxed Pronunciation in French

At first it can be hard to distinguish the slight subtleties in these French examples, but if you listen closely, you’ll soon pick up how ne is left out a lot, especially if you’re constantly around native French speakers.

To get you started, here are some listening exercises involving the French negative:

- Je n’ai rien dit (I didn’t say anything): J’ai rien dit is part of the title to a French song, “Moi j’ai rien dit” by Pierre Bachelet, where you can hear how relaxed pronunciation is used. I’ll give you a hint: The repeated refrain is “mais, moi j’ai rien dit.“

- J’sais pas or je sais pas, depending on how quick you say it, is the title to two French songs: “J’sais pas” is by Brigitte, which has minimal singing, but you can still hear how she says “j’sais pas !” so swiftly that it sounds like “chépa“). The second song is “Je sais pas” by Céline Dion, which has more lyrics to it, so listen to how she flaunts this French phrase with relaxed pronunciation.

Now, let’s put everything together into live practice:

Can you point out all the relaxed pronunciations in this short 5-minute clip on Daily Motion (France’s version of YouTube)? It’s a video from France Inter (France’s NPR), where a few Frenchies share their thoughts on Donald Trump.

Clues?

I’ll give you a few:

- At the 10-second mark the woman says, “C’est pas grave.” It sounds like she entirely omits c’est, but she doesn’t. She just pronounces it like the speed of light. She most definitely omits ne though. It’s hard to hear, so replay it over and over until you get it.

- The first guy who speaks says un-ti-peu twice, one after the other, at the 17-second mark; you can’t miss it! He says it again a little later on, can you hear it?

- At the 27-second mark he also says, “pour ceux qui voient pas” (for those who don’t realize). Here he drops the ne.

- A 1:08 he also says, “C’est pas un problème” (It’s not a problem). No ne again.

All right, that’s all I’m giving you. Continue listening for yourself!

2. Keeping Subject Pronouns

I know the words “subject pronouns” sound scary, but they’re not. I promise.

What Are Subject Pronouns?

Subject pronouns are personal pronouns that are used as the subjects of an action verb. Personal as in “people,” not so much objects. (Animals count if you treat your dog as “you.”)

In English this includes the: first (I), second (you) or third (he/she, they) person.

And in French, les pronoms sujets are:

je (I)

tu (you)

il/elle (he/she)

on/nous (one/we)

vous (“you” singular formal or “you” plural)

ils/elles (they) — masculine/feminine

Note: If you haven’t seen on yet, it’s another common, familiar (considered informal) way to say nous (we), or “one,” as in “one has to eat.” That particular example is a general, sort of sarcastic statement that includes you and other people, and since everyone must eat, then you’re obviously included in that everyone, which brings us back to “we.”

As you know, there is no such thing as “it” in French either, since everything and everyone is feminine or masculine. Check out this video for perfect pronunciation of les pronoms sujets and further explanation of on.

If you travel to France I guarantee you’ll hear on a lot more than nous, because nous is kind of obsolete. Here’s a trick to remember: Nous is only used when being written, but when French natives speak they almost always use on.

Let’s have a look at the differences between nous and on, even though they convey the same meaning:

Nous sommes à la plage.

(We are at the beach.)

Looks better when written.

On est à la plage.

(We are at the beach. / One is at the beach.)

Sounds more natural when spoken.

Everyone deserves a day at the beach, right?

(Also remember that like relaxed pronunciation, on should never be written in formal situations!)

Okay, now back to subject pronouns…

In French you cannot drop subject/personal pronouns. You must always say them—which is a helpful rule to have, since many verb conjugations have the same pronunciations. For example, let’s look at manger in the present tense:

Manger (to eat)

je mange

tu manges

il/elle/on mange

nous mangeons

vous mangez

ils/elles mangent

The four conjugations in bold above all sound the same, even though they’re clearly written differently. What doesn’t sound similar, though, are the subject pronouns (je, tu, il/elle, nous/on, vous, ils/elles), which is why they must never be dropped. To hear how the verb conjugation of manger actually sounds click here.

Once you get all those pronoms sujets down pat, lend an ear to this short radio sound bite by, yet again, France Inter. They talk about the “5th Beatle.” It’s an easy one since “he’ll” be the main “subject,” but make sure to also listen attentively to how the speakers squeeze in other subject/personal pronouns throughout.

I know this may seem like a lot to take in, but it’s okay! Because we’ve already been doing this our whole lives in our own native language.

In English the same rule follows. We cannot directly speak to anyone without specifying which person (personal/subject pronoun) we’re talking to or about—we must use “he,” “she,” “they,” “it” all the time.

There is one exception where English speakers don’t use subject/personal pronouns, and this ties into relaxed pronunciation.

For example, when speaking about yourself, instead of saying, “I’m going to get pizza, I’ll be back in five minutes” we sometimes leave out the “I” and say, “Gonna get pizza! Be back in five minutes.” (In most scenarios, we do this when answering a question or when it appears in the middle of a sentence (as in: “Well, gonna get pizza”).

Feeling less frustrated?

I hope so, because being aware of all the possibilities in our own native language will surely assist you in understanding French that much more. Just know that like in English, it’s always important to differentiate and keep subject pronouns in French!

3. Comparing to Early Modern English

To think like Shakespeare is to think in the way he poetically expressed himself (wrote and spoke) in English. You know, “thou shall…”

It’s funny because I find that modern French today is spoken in a similar style (both in structure and vocabulary) as early modern English. You might even find that some English speakers in this day and age still speak in a more extravagant, elegant manner.

The French and its language dominated Middle Aged English territory during the Dark Ages (The Norman Conquest). French was spoken by the government and higher class, because it was the language of nobles and intellectuals. It was also used in literature.

When the English tried to regain and reconquer their culture (and language) by regressing back to their roots, they took with them French eloquence, style and richness. English at the time was considered vulgar, rough and rude (spoken mostly by the lower class), so they fluffed it up with French flavor and other European influences. This ultimately resulted in an English Renaissance, also known as the “Age of Shakespeare” or the “Elizabethan Era.”

That’s why if we look at the vocabulary choice, vernacular, linguistic style, grammatical structure and word placement of Shakespeare’s era, we may find that in some ways it resembles that of today’s modern French.

So what does this mean for us French learners? Let’s dig in.

How Was French Seen in Early Modern English?

Back in the day, the English of the “Elizabethan Era” (and even before) strived to practice a form of polite, puffed-up language. The English saw how their language was slowly slipping while a French one dominated—so in comes Shakespeare (and other great writers) to save the day by creating a new, modern English that involved a lot of “copying” and “stealing” from the French and other European languages and cultures.

One example can be as simple as:

S’il te plaît

(Please)

If you want to take this phrase literally, it translates to “if you please” or “if it pleases you,” but doesn’t that seem a little too sophisticated for today’s ears?

It’s because no one speaks like this anymore. This type of phrase structure is reminiscent of the kind of “polite turn of speech” borrowed from the French, such as “at your service,” “do me the favor,” etc.

Although these more refined phrase patterns continue to persist among those who choose to use them, for the most part (with time and evolution), they’ve fallen out of fashion in English. As of today, the best translation for s’il te plaît is simply “please.”

Another example is:

Je suis d’accord.

(I agree.)

Have you ever really thought about what je suis d’accord actually means? Here’s a fun French ’60s song that paints a pretty good picture.

It might sound silly, but je suis d’accord literally translates to “I am in accordance.” Again, no one says this stuff anymore in today’s English, unless you’re some crazy, top sophisticated speaker.

In French though, je suis d’accord is constantly used in everyday conversation. It’s their way to say, “yeah, I agree,” or “yeah, you’re right,” or just, “yep.” It can be the translation of any basic short, cheap form of expressing accordance or agreement in English without actually using the word “accordance”—ironic, I know.

But if you do want to sound extra scholarly in French by expressing the word “accordance” as you would in English, then say, conformité, which is of course another lavish English word in and of itself.

Fun fact: The phrase je suis d’accord is often shortened to d’accord ! as in, “agreed!” It can also be used as a question: d’accord ? (agreed?). This trendy remark is frequently used in French.

What makes this a little easier for us is that almost 70 percent of everyday, modern French vocabulary is already part of the English language.

Here’s an example:

Je suis parti.

(I departed).

Unless you’re talking about the film “The Departed,” are at an airport on your way to France to take a flight that’s about to “depart” or sitting in a Catholic service where the priest mentions praying for the “departed,” seldom would we ever use this phrase to convey “leaving,” d’accord ?

Naturally, we English speakers would usually instead say, “I left.”

À quelle heure vous partez ?

(What time are you leaving?)

Je pars à onze heure.

(I am leaving at 11 a.m.)

“To depart” may still be heard in English, but it’s not as common in everyday speech as partir is in French. In France, je suis parti is the most popular way to say “I’m leaving.” But the fact that “depart” still exists as an “older” word in English may help us guess at the meaning of je suis parti even if we don’t know it, which is another way that thinking like Shakespeare can help.

Some French and English Shakespeare

If we take a look at pieces of Shakespearean literature, you’ll notice that the sentence structure and syntax of these English-French translations fit almost perfectly (and literally) swell together:

“L’amour ne voit pas avec les yeux, mais avec l’imagination”

“Love looks not with the eyes, but with the mind”

MND.1.1.234

“Nous savons ce que nous sommes, mais nous ne savons pas ce que nous pouvons être”

“We know what we are, but know not what we may be”

Ham.4.5.43-44

“Attendez-vous ici à la porte de notre fille ?”

“Attend you here the door of our stern daughter?”

Cym.2.3.36

“Comment l’appeliez vous, madam, cet homme dont vous parlez ?”

“How called you the man you speak of, madam?”

AW.1.1.24

And the list goes on, but as you can see, we have a few winners!

I know the early modern English versions sound and read a tad bit weird since, after all, it is Shakespeare—but what about the French versions, might they trigger a familiar look and sound? Not to mention, French is already a poetic language in itself…

In today’s present English there are a handful of expressions and vocabulary that are shared with French, but not as many as there used to be—or so we think.

This is because we don’t talk that way anymore (and for some of us, never have). That’s why I say that if you begin to think like Shakespeare, you’ll begin to understand the structure and style of today’s modern French grammar and word placement a lot more.

Have a listen to Hamlet’s famous monologue and see if you can detect the stark similarities of our early English original. If you look at the description in the YouTube video, you’ll find the French wording of the soliloquy. Compare the translations.

And if you want to test yourself on another Shakespearean masterpiece, you can buy a French translation of “Macbeth” on Amazon.

This “thinking like Shakespeare” technique can only open up the doors (of your mind) to become a better speaker and listener in French. We all know that when we delve into French, we like to think of the words in our head in English first, especially when we translate. That’s a terrible habit, but you can mould those speaking and listening skills (as well as writing) if you expand your Shakespearean-English train of thought and start using it when expressing yourself in French.

It will come naturally.

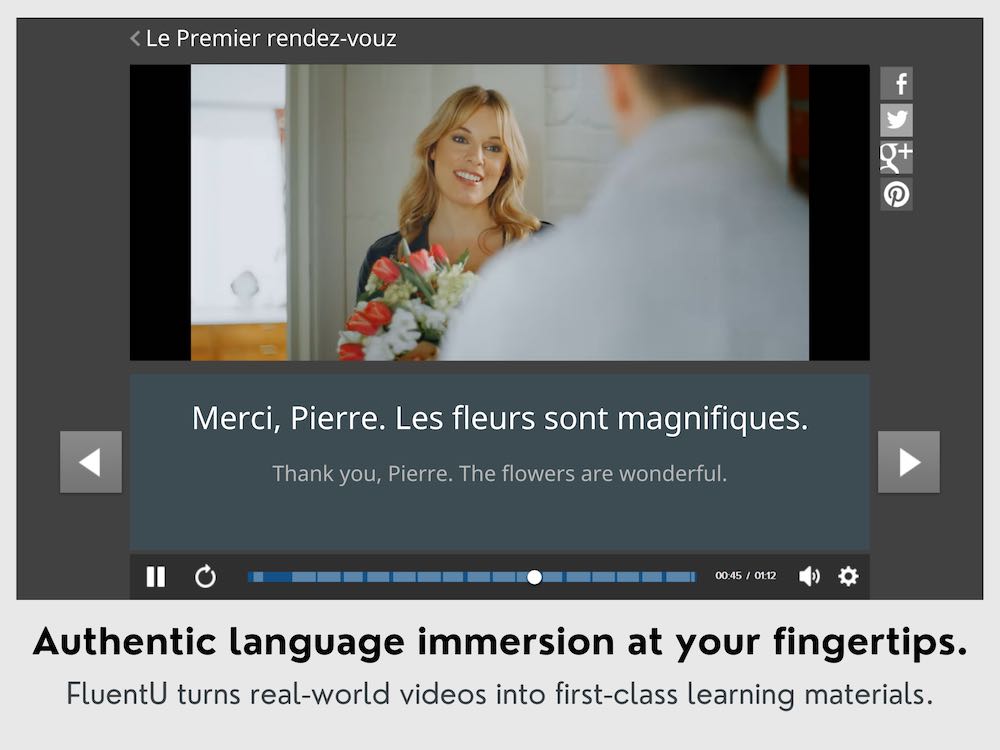

Hear French spoken by natives in the video library of FluentU:

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Now who “woulda” thought that French and English share such a harmonious relationship in language?

Use these three points and their corresponding practice methods to better understand spoken French today!

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And one more thing...

If you like learning French on your own time and from the comfort of your smart device, then I'd be remiss to not tell you about FluentU.

FluentU has a wide variety of great content, like interviews, documentary excerpts and web series, as you can see here:

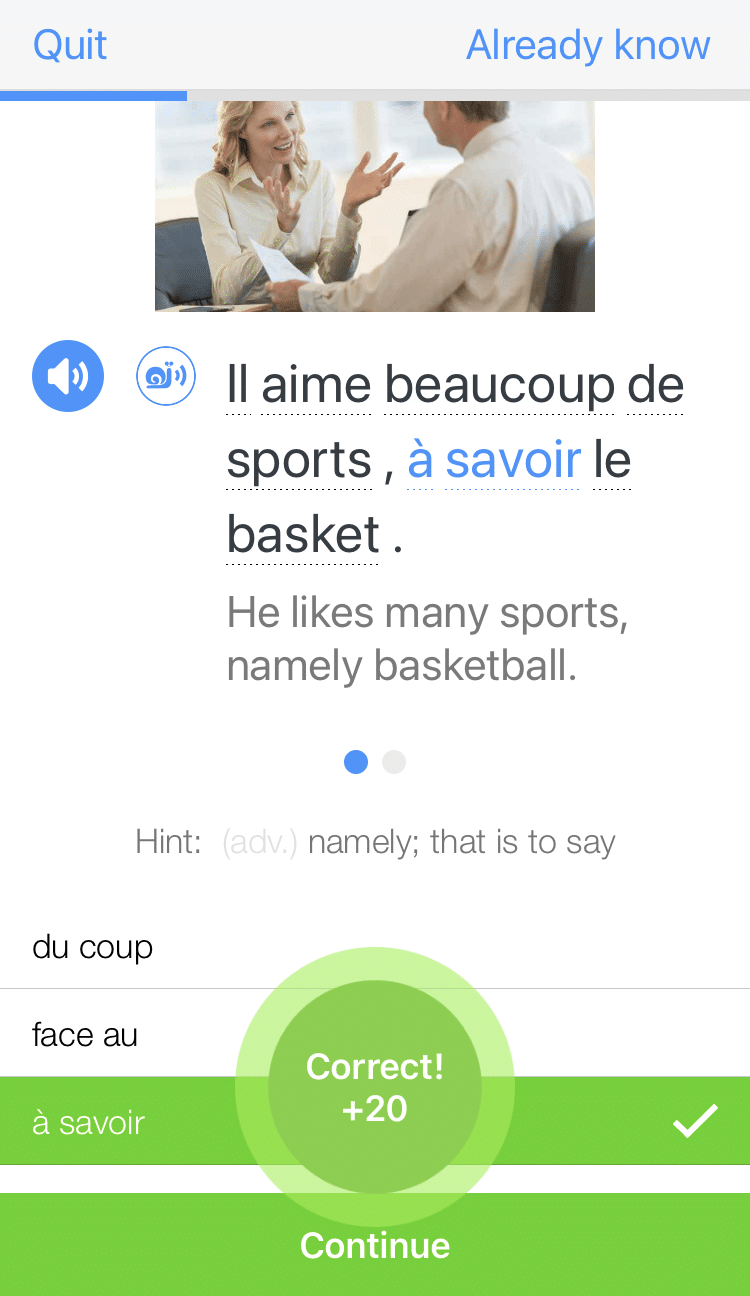

FluentU brings native French videos with reach. With interactive captions, you can tap on any word to see an image, definition and useful examples.

For example, if you tap on the word "crois," you'll see this:

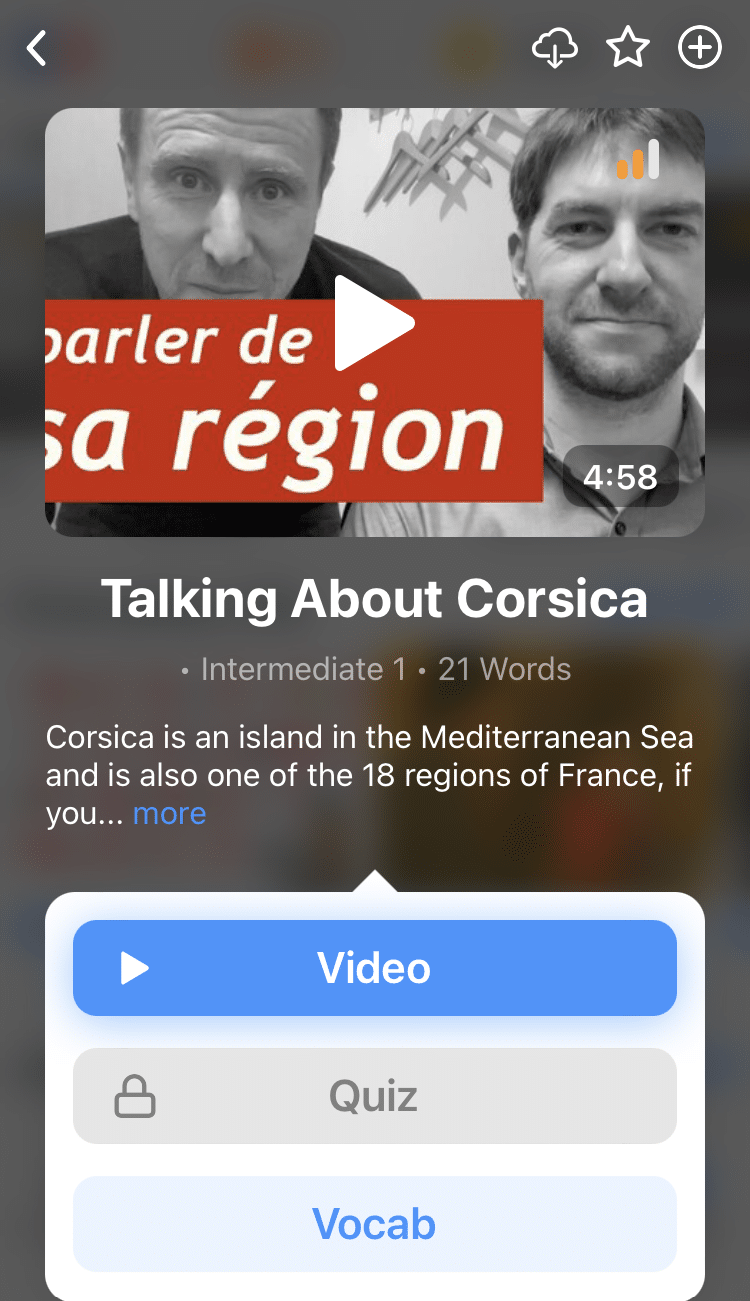

Practice and reinforce all the vocabulary you've learned in a given video with learn mode. Swipe left or right to see more examples for the word you’re learning, and play the mini-games found in our dynamic flashcards, like "fill in the blank."

All throughout, FluentU tracks the vocabulary that you’re learning and uses this information to give you a totally personalized experience. It gives you extra practice with difficult words—and reminds you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)