Made in Acadia: The History, Evolution and Unique Expressions of Acadian French

“I’ll take Francophone Trivia for $200, Alex,” your opponent says.

“The name of this variety of French sounds like a place to play video games.”

After a string of incorrect guesses (Nintendique? Atarièle?), Alex shakes his head solemnly. Then he locks his gaze on you. Your palms are sweaty. You click on the buzzer.

“What is…Acadian!” you shout out, hoping you were paying enough attention during your French history class.

“You are correct!” Alex beams, and gives you control of the board.

Contents

- Acadian: One of the Many Global Varieties of French

- Made in Acadia: The History of Acadian French

- Where Is Acadian French Spoken Now?

- How Acadian French Parted from Standard French

- How Does Acadian French Differ from Standard French?

- Chiac, an Emerging Acadian Vernacular

- And one more thing...

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Acadian: One of the Many Global Varieties of French

Acadian history is fascinating, and not at all trivial.

It spans nearly half a millennium, and it impacts language and culture in many parts of North America. Although not as widely recognized as Québec French, it’s every bit as valuable to know about. It’s a truly unique variety of the French language that acknowledges its seventeenth century roots while continuing to evolve for Acadian life in the 21st century.

Like the many types of French around the world, including Algerian French, Louisiana Cajun French, Belgian French, Marseillais French, and Haitian French, Acadian French has its own special pronunciations and characteristics. It’s even distinct from its better-known Francophone neighbor, Québecois French.

All of these global varieties of French are best explored by listening to native speakers. One way to do this is by using a virtual immersion platform. FluentU’s program, for example, is video-powered and features content from all over the French-speaking world.

Let’s begin by traveling time and space to 17th century New France, where Acadian French was born.

Made in Acadia: The History of Acadian French

The Origins of Acadian French

So, where did Acadian French come from? How did it all begin?

The word Acadia may have derived from Arcadia, a region in Greece. Explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano used “Arcadia” to describe the woodland beauty of both Virginia and Maryland, as reflected in Giacomo Gastaldi’s 1548 map of the area. The word was later applied to the whole East Coast of North America, and then specifically to parts of what are now the Maritime provinces in Canada.

It’s possible that l’Arcadie (Arcadia) became l’Acadie as French traders picked up on words from the local Mi’kmaq tribe; -akadie is part of several placenames in Míkmawísimk (the Mi’kmaq language), and means “place of abundance.”

It’s equally possible that Acadie (-akadie) came directly from the Mi’kmaq language, completely unrelated to the Arcadia of Greek geography and mythology.

From France to Acadia.

Cartographer Samuel de Champlain was part of the French expedition that explored the area of Acadia. The earliest French settlers came to Acadia in 1604, primarily from Loudun and Poitou in the West of France. A smattering of people from other regions of France, and even a few from Flanders and Portugal, joined the colony.

Fallout from the Reformation included plague and famine, and drove thousands more from Picardy, Brittany and Normandy to Champlain’s North American colony. Many of these were indentured servants, who traded five years of their lives for transportation to Acadia.

Multinational government.

A long-disputed territory, Acadia had a series of governors appointed by France, Britain, Scotland and Denmark. French Acadian culture grew stronger and more self-sufficient, due to the instability of the shifting political control of the territory.

The two strongest rivals for control of Acadia were France and Britain.

War time in the Maritimes.

As a prelude to the British conquest of Acadia in June 1755, a series of wars was fought for control of Acadia.

These conflicts included the well-known French and Indian War. Several indigenous tribes (members of which had intermarried with the Acadian French settlers) fought on the side of the Acadian French. These tribes included the Mi’kmaq, the Ottawa and the Shawnee. (The Cherokee, Iroquois and Catawba fought with the British forces.)

Farewell to Nova Scotia.

In late summer through autumn in 1755, the Acadian French—most of whom refused to swear a loyalty oath to the British crown—were forcibly removed from Acadia by the British. Their houses and barns were burned, and some who refused to leave were shot. As many as 18,000 Acadians were displaced, and about 8,000 lost their lives. This mandatory exile has become known as le Grand Dérangement (the Great Upheaval).

Some Acadian families tried to stay in Nova Scotia, but they were restricted to Fort Edward, Fort Cumberland, Halifax and Annapolis Royal.

With the fall of Acadian stronghold Louisbourg in 1758, a new wave of the Acadian French exodus commenced. Île St-Jean (now Prince Edward Island) sent its former francophone inhabitants as far away as Baltimore, Maryland (where a French Town was established at St. Charles and Saratoga Streets) and Charleston, South Carolina.

While some of the exiled Acadians found new homes in several different American colonies (including Pennsylvania, Maryland, New York, Georgia and parts of New England), many of them endured dangerous and unsanitary conditions aboard exile ships. Hundreds of the “French Neutrals,” as the Acadians were then called, died in the process of relocation.

Where Is Acadian French Spoken Now?

Back home again in New Brunswick.

Although New Brunswick had not been home to many Acadian French prior to le Grand Dérangement, many exiled Acadians established territory along the St. John River around 1756.

A series of conflicts with the British forced many Acadians out of the area, but several stubborn Acadians stayed on. Eventually, some of those who had left during the British raids returned to the area.

Living on the edge (of the border).

A few families returned to Nova Scotia and other parts of Acadia after the Seven Years War ended. However, they found their lands had been usurped by English settlers.

They were able to carve out some spaces for themselves in the north and south of Cape Breton Island, as well as the western edges of Nova Scotia proper—namely, near Sainte-Anne-du-Ruisseau, Saulnierville and Wedgeport.

Some of the returning Acadians found homes right over the Québécois border. They established Petites Cadies (Little Acadias) in villages such as Saint-Grégoire-de-Nicolet, Saint-Gervais-de-Bellechasse and L’Acadie.

Today, over a million Québec residents, or roughly 15% of the population, have Acadian ancestry.

South of the border.

Saint John Valley in the state of Maine was part of the original Acadian settlement. Long before the United States became a nation, French speakers in the Acadian region put down roots in what was later to become a border state with Canada.

More Acadians came to settle in the Upper Saint John Valley in Maine in the 1780s, although historians hold differing theories as to why they migrated.

Sadly, many Maine residents in the Saint John Valley have reported that the school systems forbade the use of French in the schools prior to 1970. Teachers—many native French speakers themselves—were obligated to chastise children for speaking French in the classroom. The shame caused a decline in French speaking by younger Acadians in Maine.

In 1970, however, school programs featuring bilingual French-English instruction were introduced. These bilingual programs seemed to increase French fluency somewhat. However, parents were reluctant to encourage their children to learn the Valley French that was part of their Acadian heritage. The stigma against French from their own childhoods still haunted them.

With distant Cajun cousins.

Acadians arrived in Louisiana by way of New York, after le Grand Dérangement, starting in 1764.

By 1785, other Acadians entered Louisiana after having been exiled from Acadia to England or France. Many of these came over the course of seven Acadian excursions from France, by the 1781 decree of King Louis XVI.

The term “Cajun,” later used to describe the descendants of the Acadians in Louisiana, derives from a corruption of the word acadien (Acadian). The Acadian heritage and influence in Louisiana persists to modern times.

Louisiana is still considered a bastion of French culture in the United States. In New Orleans, you can enjoy beignets (sugar-covered yeast doughnuts) and laisser les bons temps rouler (let the good times roll)—not to mention participate in a world-famous Mardi Gras celebration.

But the French culture isn’t limited to the French Quarter. Although incursions of mainstream America periodically seemed to threaten the Cajun way of life, its heritage also continues in the bayou and beyond. There, descendants of Acadian exiles still speak a variation of Acadian French. Louisiana’s Office of Cultural Development works to keep this legacy alive through CODOFIL, the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana.

How Acadian French Parted from Standard French

Acadian French can’t be that different. It’s still French, right?

Bien sûr! (Of course!) But if you learned standard French—also known as “France French,” Parisian French or Metropolitan French—then Acadian French may seem a bit strange to you.

Think about how many different ways English is spoken around the world. English in the United States is certainly not the same as in New Zealand, for example. Centuries of history and miles of geography distinguish the two groups of anglophones. And, as George Bernard Shaw once remarked, “England and America are two countries separated by a common language.”

In much the same way, Acadian French has undergone many changes since the first francophone settlers in Acadia came over from France. First of all, the settlers needed words for previously-unknown flora and fauna. They borrowed some of these words from their new neighbors, the Mi’kmaq.

Le Grand Dérangement (the Great Upheaval) only served to change the language further, as the exiled Acadians picked up new words and ways of speaking from their travels.

Meanwhile, the French spoken back in Europe was also changing over time. Entirely different events shaped the linguistic changes in France and Acadia.

The establishment of l’Académie française (the French Academy) in 1635, three decades after French settlers first reached Acadia, imposed language reforms within the mainstream of the French Empire. These changes did not directly reach the Acadians, who continued to use many of the antiquated words and nautical terms brought across the ocean by their ancestors.

More than four hundred years have now passed since the first French settlers came to Acadia. At least three hundred years have gone by since influx of new French settlers ceased. After all those centuries, Acadian French is notably different in several ways from its original European relative.

How Does Acadian French Differ from Standard French?

Unintentional Verlan.

In France, members of the youth culture deliberately reverse the syllables in certain words to create a special kind of slang called Verlan.

In Acadian French, metathesis—the reversal of sounds in neighboring syllables—is a common part of the language.

The classic example of this is found in the middle of the week: mercredi (Wednesday) in Standard French becomes mécordi in Acadian French. Similarly, je (I) transforms into euj.

Roll me away.

Unlike their fellow French speakers in France, the Acadians never developed the uvular rhotic, or guttural “r,” that sets standard French apart among the modern Romance languages.

Like speakers of Spanish, Italian, Portuguese and many other languages, French-speaking Acadians still use the alveolar rhotic, the rolled or trilled “r” sound, that used to be part of the French spoken in France.

Ch-ch-ch-changes.

In Acadian French, you would ask for a tchuillère (spoon) for your soup—because that’s how your Acadian host would pronounce cuillère. And you could speak to “tchelqu’un” (quelqu’un, someone) about how the word Acadien (Acadian) morphed into Cajun around the time the exiled settlers reached Louisiana.

This phenomenon of replacing existing consonants with a “ch” or a “juh” sound is called affrication, and it helps set Acadian French apart from other versions of the language.

Short and sweet.

French doesn’t linger over its syllables. Salut (Hello) is s’lut in Acadian French. There may be such a thing as a long goodbye in Acadia, but there are no long hellos.

And drop that -re sound. Drop it right now! Because if even if you’re lib’ (libre, free) to buy a timb’ (timbre, stamp) in Acadia, you certainly don’t have time to stand around jawing about it.

Your Acadian host won’t be talking about it, either. He’s too busy planting an âbe (arbre, tree).

17th-century time capsule.

Acadian French is a living time capsule, preserving French words commonly used three or four centuries ago.

It’s very similar to the strong traces of Anglo-Saxon and Elizabethan usage found in modern Appalachian English, also known as Southern mountain dialect.

Unlike their French-speaking Canadian neighbors, the Québécois, the Acadians were isolated from fellow francophones by a history of political unrest, war and exile. Therefore, the French they speak retains characteristics and vocabulary that are now considered obsolete in France and other French-speaking parts of the world.

The French that Acadians speak is different, too. Instead of the typical first-person verbs of avoir, to have, or être, to be (j’avais or j’étais in common French), they’ll use a plural—j’avions or j’étions. And their vocabulary is tinged with words of the sea. Quebecois French would call a staircase un escalier. But Acadian French would call a staircase une échelle, which usually designates a ladder, such as those found on a ship.

— Atlas Obscura: New Hampshire Mill Workers Invented a New Type of French

Acadian French shares some words and slang with Québec French, such as caler (to sink), chu for je suis (I am) and asteur for maintenant (now). But many words are particular to Acadian French. For example:

| Acadian French | Québécois French | Standard/European French | English |

| pomme de pré | canneberge (for the fruit itself) / atoca (for cranberry sauce, specifically) | canneberge | cranberry |

| timber | se bêcher | tomber | to fall |

| échelle | escalier | escalier | stairway |

Many Acadian words hearken back to words that are now considered obsolete in Standard French. Others incorporate local words from Acadia:

| Acadian French | Standard/European French | English |

| aveindre | chercher / attraper | search / capture |

| marabout | grincheuse | grumpy |

| galance | balançoire | swing |

| tiriaque | réglisse | liquorice |

| quérir | chercher | to look for |

| ramandeux | quémandeur | beggar |

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Chiac, an Emerging Acadian Vernacular

The un-franglais.

Most French learners have heard of franglais, the haphazard usage of English words in French. Le week-end (weekend) and le shopping (shopping) have been part of common French usage for decades.

Acadian French has given birth to its own hybridization, called Chiac.

Possibly drawing its name from the town of Shediac in New Brunswick, Chiac is a mixture of English and Acadian French. It’s considered distinct from both franglais and standard Acadian French.

French forms, mixed vocab.

Chiac uses Acadian French syntax and vocabulary, with some structures and words borrowed from both the English and Mi’kmaq languages.

The language of youth.

Chiac is increasingly embraced by younger people as a vernacular. It’s now making a bigger splash in the media, with television shows such as the animated Acadieman—not to mention musicians like Lisa LeBlanc and Radio Radio, who perform their songs in Chiac.

There’s some concern that the use of a mixed idiom such as Chiac may erode Acadian French as a distinct form of the French language. On the other hand, there are those who see Chiac as a preservation of Acadia’s unique heritage—and a source of pride, especially for the younger generations.

Acadian French holds an important place in the tapestry of francophone cultural and history.

It remains a living link to the past.

And it continues to represent the cultural identity of a group of people who fought, faced exile and remain proud of their rich history and heritage.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And one more thing...

If you like learning French on your own time and from the comfort of your smart device, then I'd be remiss to not tell you about FluentU.

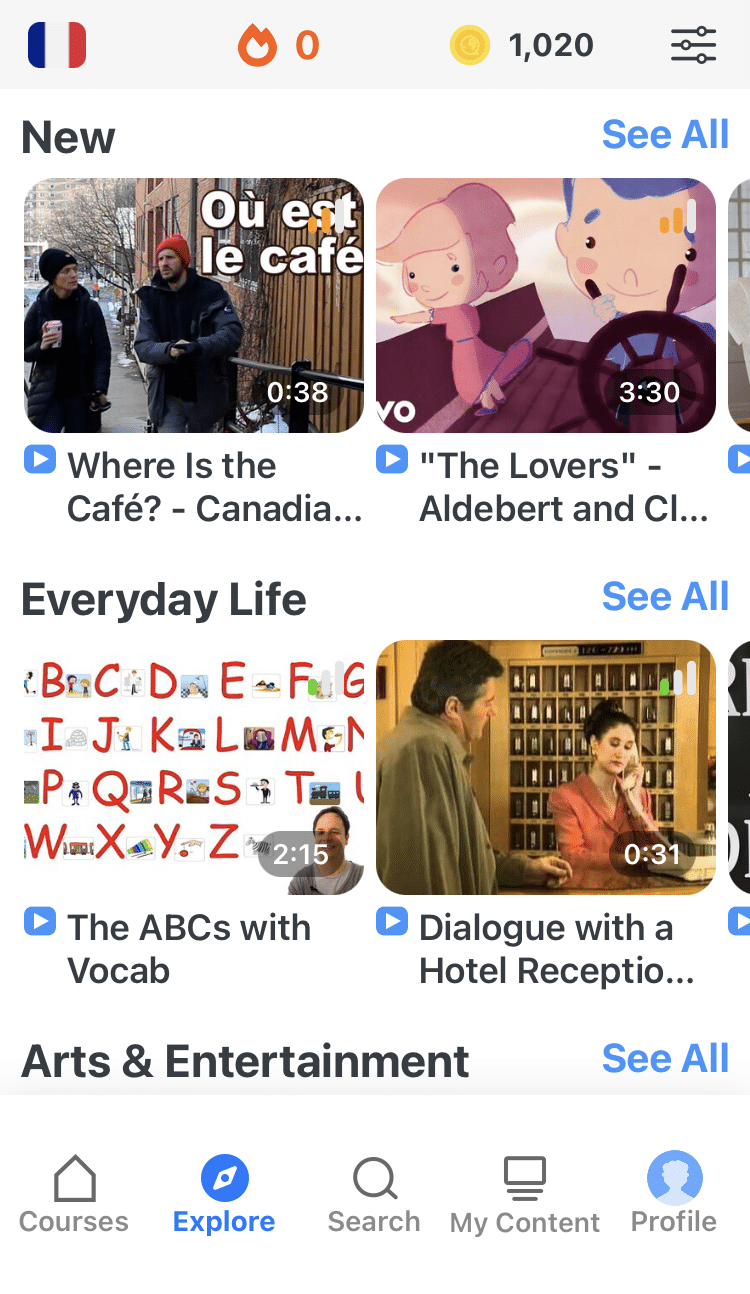

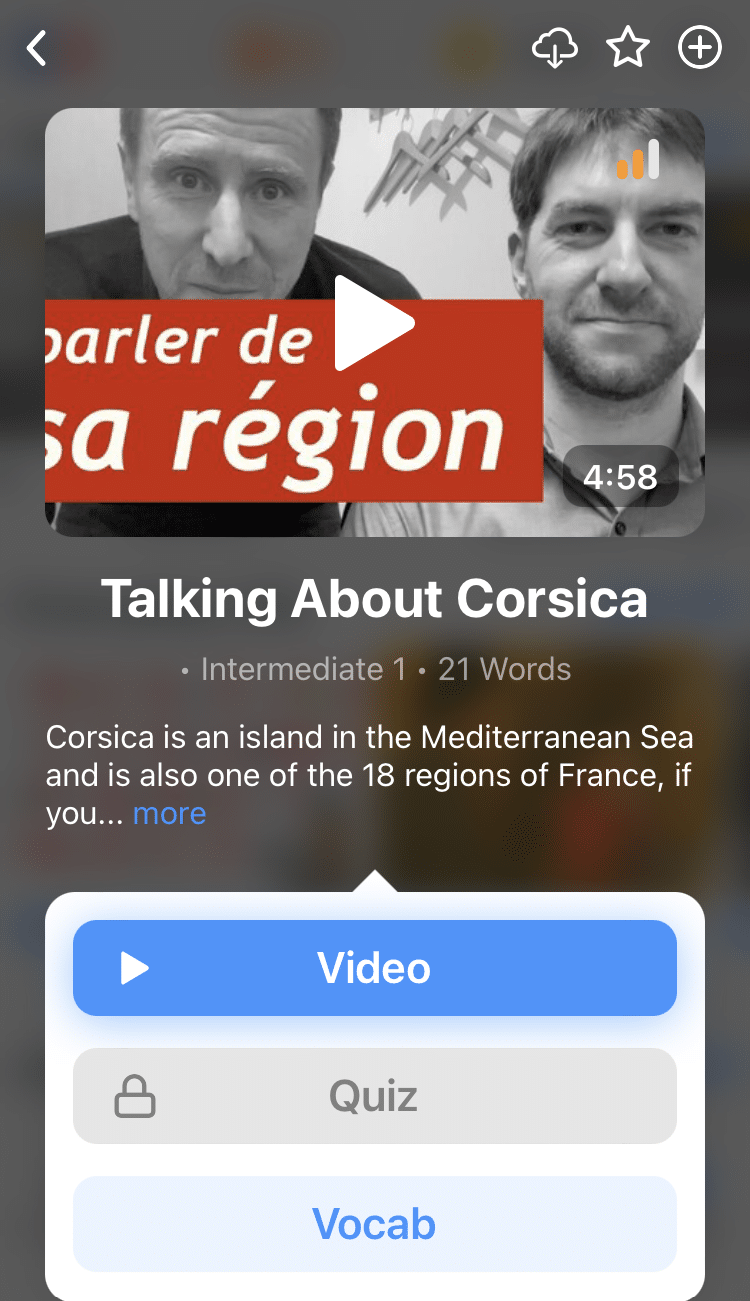

FluentU has a wide variety of great content, like interviews, documentary excerpts and web series, as you can see here:

FluentU brings native French videos with reach. With interactive captions, you can tap on any word to see an image, definition and useful examples.

For example, if you tap on the word "crois," you'll see this:

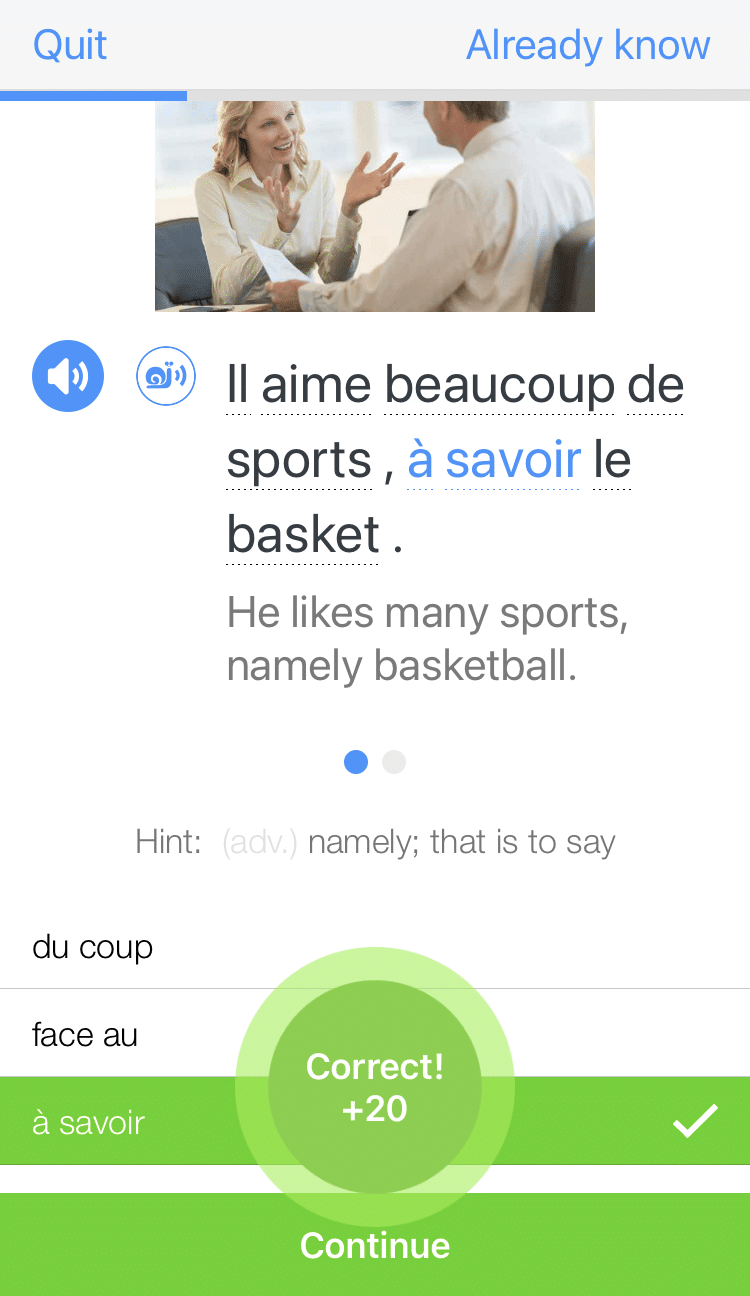

Practice and reinforce all the vocabulary you've learned in a given video with learn mode. Swipe left or right to see more examples for the word you’re learning, and play the mini-games found in our dynamic flashcards, like "fill in the blank."

All throughout, FluentU tracks the vocabulary that you’re learning and uses this information to give you a totally personalized experience. It gives you extra practice with difficult words—and reminds you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)